Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

I Hear You, Matt Damon

In school choice circles, a lot of people don’t much care for actor Matt Damon, at least his education politics. (I’m not sure where they stand on The Bourne Identity or Stuck on You.) Damon—son of education professor Nancy Carlsson-Paige—has been a vocal advocate for government schooling, and is the narrator of the documentary Backpack Full of Cash, which you might recall is the film those outraged over Andrew Coulson’s School Inc. say PBS must show to balance out perspectives. But here’s the thing: Damon sends his own kids to private school!

I am supposed to be outraged by the apparent hypocrisy, but I don’t think Damon’s selection falls under that heading. Damon and many progressives love public schooling but don’t like what it has become, especially under the standards-and-testing tidal wave of No Child Left Behind, and the only somewhat less inundating Every Student Succeeds Act. They don’t care for the reduction of education to basically a standardized test score. As Damon, who attended progressive public schools in Cambridge, MA, has said, “I pay for a private education and I’m trying to get the one that most matches the public education that I had, but that kind of progressive education no longer exists in the public system. It’s unfair.”

No doubt lots of people—choice fans and detractors alike—who want education to be more than a score sympathize with Damon’s frustration. The problem is that Damon champions exactly the wrong system to get sustainable change. By its nature, public schooling, if not doomed to reduction to simple metrics, is in constant, near-death peril of it.

When people can’t vote with their feet—which is very tough to do in a system in which where you go to school depends on where you can afford a home—their only hope to make schools do what they want is government action. But government is controlled by politics, which is itself driven by soundbites. And what is ideal for a soundbite on whether schools are “working”? Why test scores, of course! “The scores are up,” or “the scores are down,” or “25 percent of the kids are proficient,” and so on.

The key to escaping such peril is not hoping that nick-of-time, death-defying, Jason Bourne-esque political miracles will constantly save us, but basing education in freedom. Attach cash to students—via “backpacks,” if you must—give educators autonomy to teach and run schools as they see fit, and ground accountability in educators providing schools to which parents willingly entrust those backpack-bearing kids.

Of course, there is much more that is problematic about government education than just simplistic standardization. Far more deeply, if it is “unfair” that Damon can’t find the progressive schools he wants in the public system, it also unfair that many religious people—who by law cannot get the education they want in public schools—or Mexican Americans, or countless other people are also unable to access the education they want. Thankfully, the key to getting fairness for them is the same one to getting fairness for Damon: school choice.

Don’t blame Matt Damon for his choices. Blame the choice-killing system he defends.

Related Tags

The Two-Per-Cent Solution

The Fed’s persistent failure to reach its 2 percent inflation target ever since that target was first made explicit in 2012 has elicited a great deal of commentary in the last couple months, from economists, journalists, and some Fed officials themselves. And well it ought to, for whatever one may think of the Fed’s choice of target, the fact that the Fed has been persistently falling short of it suggests that something is awry, if not with U.S. monetary policy, then perhaps with the U.S. economy more generally.

Although plenty of explanations have been offered for the inflation shortfall, none of them is even close to being satisfactory. Bias or “noise” in the inflation numbers? Bias would explain things if the Fed were targeting some supposedly “ideal” measure of inflation. But it isn’t: it’s targeting the rate of change of the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) index, and so long as that measure of inflation falls below the Fed’s target, the Fed isn’t “really” hitting its self-assigned target, even if the “real” inflation rate is higher than the PCE index suggests. As for noise, it should make the Fed just as likely to overshoot as to undershoot its target. Unemployment still isn’t quite low enough? Despite what some foolish Phillips-curve reasoning suggests, putting more people to work doesn’t make things more expensive. The public’s long-run inflation expectations are down? No doubt. But surely that’s a result, rather than a cause, of the persistently low values of actual (or measured) inflation?

Aggregate Demand is Part of the Story (But Only Part)

Of existing explanations, the least question-begging emphasize the fact that total spending, or its statistical counterparts such as nominal GDP, just hasn’t been growing rapidly enough to achieve the Fed’s inflation target. As Mickey Levy puts it in a paper he gave at last week’s SOMC meeting,

Obviously, if nominal GDP had accelerated in response to the Fed’s aggressive easing as planned, both wages and inflation would have risen faster, and inflationary expectations would be higher.

Scott Sumner has made essentially the same point: “The only way to have low inflation despite low RGDP growth,” he observes,

is if the Fed has such a tight monetary policy that NGDP growth remains slow. And that’s exactly what they’ve done since 2009. If you produce 4% NGDP growth year after year after year [when the norm has been substantially higher] then why be surprised that inflation remains low?

In fact, as David Beckworth pointed out recently, using the chart reproduced below, since the third quarter of 2009 NGDP has grown at an average rate of just 3.4 percent, compared to 5.4 percent between 1990 and 2007 and 5.7 percent for the full “Great Moderation” period of 1985–2007:

According to Beckworth the decline reflects “a monetary regime change” consisting in part of the Fed’s having failed to allow spending to “bounce back at a higher growth rate during the recovery” as it had done in past recessions.

But while explanations that attribute the Fed’s failure to reach its inflation target to slow NGDP growth have the distinct virtue of taking the equation of exchange (MV = Py) seriously (which is more than can be said for some of the others), they still beg the question: why hasn’t the Fed achieved higher NGDP growth?

To observe that it hasn’t done so because it hasn’t been directly targeting NGDP won’t do. After all, a 2 percent inflation target implicitly calls for whatever NGDP growth rate it takes to achieve 2 percent inflation. Arguments to the effect that the Fed has failed to achieve 2 percent inflation because it has failed to achieve 5 percent NGDP growth (or some such number) instead of 3.4 percent growth do no more than state the original question in slightly modified form.

The Regime Change that Matters

In fingering “regime change” Beckworth gets closer to the truth. Only the regime change that really matters isn’t the shift away from level to rate targeting that he emphasizes. It’s the switch, in October 2008, from the Fed’s conventional monetary control arrangements, with a market-based fed funds target achieved with the help of open-market operations, to its current IOER-based (leaky) “floor system” — in which the fed funds rate is moved up or down by raising the rate of interest the Fed pays on banks’ excess reserves, either alone or together with the rate it offers in its overnight reverse repurchase (ON-RRP) agreements.

What does the Fed’s switch to a floor system have to do with the low inflation and NGDP numbers we’ve been seeing ever since? Bear with me, and I’ll explain.

To do so I must first explain in a bit more detail how a floor system works. In so doing, I’m going to abstract from the role of ON-RRPs, for those aren’t actually part of an orthodox floor system, in which the IOER rate alone serves as the central bank’s policy rate. In the U.S., the situation is complicated by the fact that various GSEs keep balances at the Fed, but aren’t eligible for interest on those balances. Consequently banks and those GSEs can mutually profit by having the GSEs lend their excess Fed balances to the banks for a rate somewhere between the IOER rate and zero. To partially address this “leak” in what would otherwise have been a solid IOER-based federal funds rate floor, the Fed offered the GSEs and some other non-bank financial institutions the opportunity undertake reverse repos with it, thereby establishing a solid ON-RRP subfloor below the leaky IOER-rate floor. This arrangement serves to limit the extent to which the effective fed funds can fall below the IOER, although it still allows it to vary between that rate and the ON-RRP rate, as can be seen in the chart below. Those two rate therefore serve as upper and lower “bounds” of the Federal Reserve’s post-2008 fed funds rate target “range.”

A Floor System Calls for Substantial Excess Reserves

Abstracting, then, from the “leakiness” of the Fed’s IOER-rate floor, and the presence of an ON-RRP rate sub-floor, the basic idea of a floor system is that the interest rate on excess reserves displaces the fed funds rate as the key monetary policy rate. That’s because, in an ideal (leak-free) floor system, banks would neither lend nor borrow federal funds, whether from other banks or from non-bank financial institutions. Instead, they find it more profitable to hold excess reserves. A necessary and sufficient condition for this is that the IOER rate be sufficiently high relative to equivalent private-market rates of interest. In that case, banks will find it more attractive to hold excess reserves than to lend in private overnight markets, including the fed funds market. So long as they accumulate sufficient excess reserves, they can also protect themselves against any need to borrow funds overnight to meet either their net settlement needs or their legal reserve requirements. Of course the banks will find it especially easy to accumulate excess reserves if the Federal Reserves creates large quantities of fresh reserves, as the Fed did through its various rounds of quantitative easing. Still in the long run what matters most for the existence of a floor system is, not that any particular nominal quantity of reserves should be available, but that banks should have a robust demand for excess reserves, as they will only so long as such reserves yield a sufficiently attractive return.

In an orthodox floor system, such as is established when these conditions hold, the market for bank reserves functions as in the diagram below, taken from Marvin Goodfriend’s locus classicus on the subject:

As the diagram shows, so long as banks hold sufficient excess reserves, monetary policy becomes a matter of making desired changes to the IOER rate alone. Through arbitrage those changes will influence other interest rates. Changes in the actual stock of bank reserves, on the other hand, are neither necessary nor sufficient to influence the general state of interest rates. Instead, banks holdings of excess reserves increase and decline in lock-step with shifts in the supply of total reserves, leaving not only interest rates but lending, spending, and the inflation rate largely unchanged.

Whence the Deflationary Bias?

You’re still wondering what all this has to do with the Fed’s persistent undershooting of inflation. Trust me, I’m getting there!

It might appear that the switch from a conventional to a floor system should make no difference in the Fed’s ability to pursue whatever policy it wishes. After all, all that has changed is the mechanism by which the Fed pursues its policy targets, rather than its ability to set and pursue those targets. Whereas before, to loosen (or tighten) policy, the Fed may have had to increase (or reduce) the available supply of bank reserves, now it only has to lower (or increase) the IOER rate. So, why shouldn’t it be able to lower that rate enough to get inflation to 2 percent, or whatever other figure it prefers?

The answer is that, while in principle it could achieve a higher rate of inflation by lowering its IOER rate sufficiently (or, in the actual case, by lowering both its IOER and ON-RRP rates sufficiently), it cannot generally achieve any inflation rate that it wants while also maintaining a floor system. On the contrary: as I’ll explain in a moment, although the masterminds behind the Fed’s turn to a floor system don’t seem to have realized it, maintaining such a system necessarily introduces a deflationary bias in monetary policy.

To see why, recall that, to maintain a floor system, the IOER rate has to be high relative to corresponding market rates. Otherwise banks won’t be inclined to accumulate and sit on substantial excess reserves. Instead, they’ll increase their lending in wholesale and other markets that offer them better risk-adjusted returns. To serve as a floor (and forgetting about GSE-based leaks), the IOER rate must be an above-market rate.

That the Fed’s IOER rate has in fact been kept above corresponding market rates is easily shown by comparing it to its closest private-market counterparts. Of those the closest is probably the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation’s GCF (General Collateral Finance) U.S. Treasury and Agency-Based MBS Repo rate index. The next figure shows how the IOER rate has generally been kept above, and often well above, that comparable market rate:

A comparison of the IOER rate and yields on various shorter-term Treasury securities tells a similar story:

As can be seen, whenever market rates have tended to increase, the Fed has made a point of having its IOER rate keep up with those changes. It has done so, moreover, despite the fact that it has persistently fallen short of its inflation target. Clearly the rate adjustments cannot be justified by appeal to the Fed’s desire to stick to that target. They can, on the other hand, be accounted for as inevitable consequences of the Fed’s determination to keep its shiny new (albeit leaky) floor system going.

A Wicksellian Perspective

I’m still not quite done, for I’ve yet to explain in the clearest way possible why a floor system introduces a low inflation bias in monetary policy. Doing that requires that I appeal to Knut Wicksell’s understanding of how an economy’s rate of inflation depends on the relation between its central bank’s chosen policy rate and the economy’s corresponding “natural” rate of interest. According to Wicksell, a policy rate set below its “natural” level will tend to promote inflation, while one set above its natural level will tend to promote deflation.

One can quibble with the details of Wicksell’s argument, as I myself have done by noting that a nation’s inflation rate depends, not just on its central bank’s monetary policy stance, but on the state of economic productivity, among other things. (For this reason I think it better to speak of an above-natural policy rate inevitably leading, not necessarily to deflation or disinflation, but to an excessively low rate of NGDP growth.) The point remains that a central bank that tends to set its policy rate too high will also tend to generate less inflation than it wants.

To see that this is exactly what will happen if a central bank insists on preserving a floor system, imagine that we are back in the pre-2008 monetary control regime, with no IOER and a market-determined fed funds rate. Assume as well that the rate is both on target and at it’s “natural” level — that is, the Fed’s target is consistent with a modest (if not zero) rate of inflation.

Now suppose the Fed decides to switch to a floor system. To do that, it first has to set an IOER rate at least as high as the established fed funds rate, and therefore either at or above the natural funds rate, so as to encourage banks to accumulate excess reserves, in anticipation of boosting the supply of reserves. These steps are needed to get the fed funds market onto the flat portion of the reserve demand schedule shown in Goodfriend’s diagram above. Thenceforth, to stay in the new regime, as natural rates increase the Fed must increase the IOER as well. While a below-natural IOER rate will undermine the floor system by causing banks to shed their excess reserves, an above-natural IOER rate won’t. A permanent floor system is, for this reason, a recipe for monetary over-tightening.

Obviously, if the Fed decides to introduce a floor system at a time when policy is already tight, so that the going fed funds rate is already an above-natural rate, the switch will tend to result in additional over-tightening, since it must involve introducing an IOER rate that’s at least as high as the already excessively high established fed funds rate. Something like this appears, in retrospect, to be what happened in October 2008.

A Missing Piece

My explanation for the Fed’s persistent tendency to undershoot its inflation target is still not quite complete. For it rests on the underlying premise that the Fed is determined, by hook or by crook, to maintain a floor system of monetary control. What proof have I of that?

It is a good question. My answer is, first of all, that the proof lies at least partly in the pudding. For, as I’ve stated, were it not for its determination to keep a floor system in place, it would be difficult to explain the Fed’s insistence upon raising its policy rate despite falling short of its inflation target. Further evidence consists of the Fed’s present normalization plan, which calls for eventual increases in the federal funds rate by close to 175 basis points. So far as Fed officials have indicated, that increase is to be achieved entirely by means of equivalent increases in the IOER rate. In short, if the Fed has any intention of ever returning to its pre-IOER operating system, or to a true “corridor” system in which the IOER rate serves not as an upper but as a lower bound for the fed funds rate, it has given no indication of it. On the contrary: having spoken to several Fed insiders on the matter, I’m assured that the Fed has every intention of sticking to the present system.

Why it should wish to do so is a different matter. I’m pretty sure that part of the reason is that Fed authorities are themselves unaware of the over-tightening bias present in a floor system. They applaud, on the other hand, the fact that a floor system allows them to separately manage interest rates on the one hand and the state of bank liquidity on the other. In recent Congressional testimony,I likened the Fed’s gain in flexibility in a floor system — its being able to set its policy rate however it likes, while altering the supply of bank reserves however it likes — to the gain an automobile owner might secure, in being able to turn the wheel as much as she likes, while also stepping on the gas peddle however much she likes, by shifting from Drive to Neutral. The problem, of course, is that, while the driver seems to have more options, the car no longer gets her where she wants to go.

The Solution

What do you suppose it is? The Fed has to abandon its misguided floor system, the sooner the better, by moving to reduce its IOER rate, instead of increasing it — as it has been planning to do. As the rate falls from above market to below market, the money multiplier will revive; and that revival will, believe you me, prove more than adequate to boost spending enough to get the PCE inflation rate to 2 percent — and beyond. To keep it from getting too high, the Fed will have to plan on more aggressive balance sheet reductions or resort to its Term Deposit Facility or both. All this is difficult, but not impossible. The Fed can certainly do it if it tries. What it can’t do is stick to the present floor system and reliably hit its inflation target.

Related Tags

Poll: Public Distrusts Wall Street Regulators as Much as Wall Street, Say Gov’t Regulators Are Ineffective, Biased, and Selfish

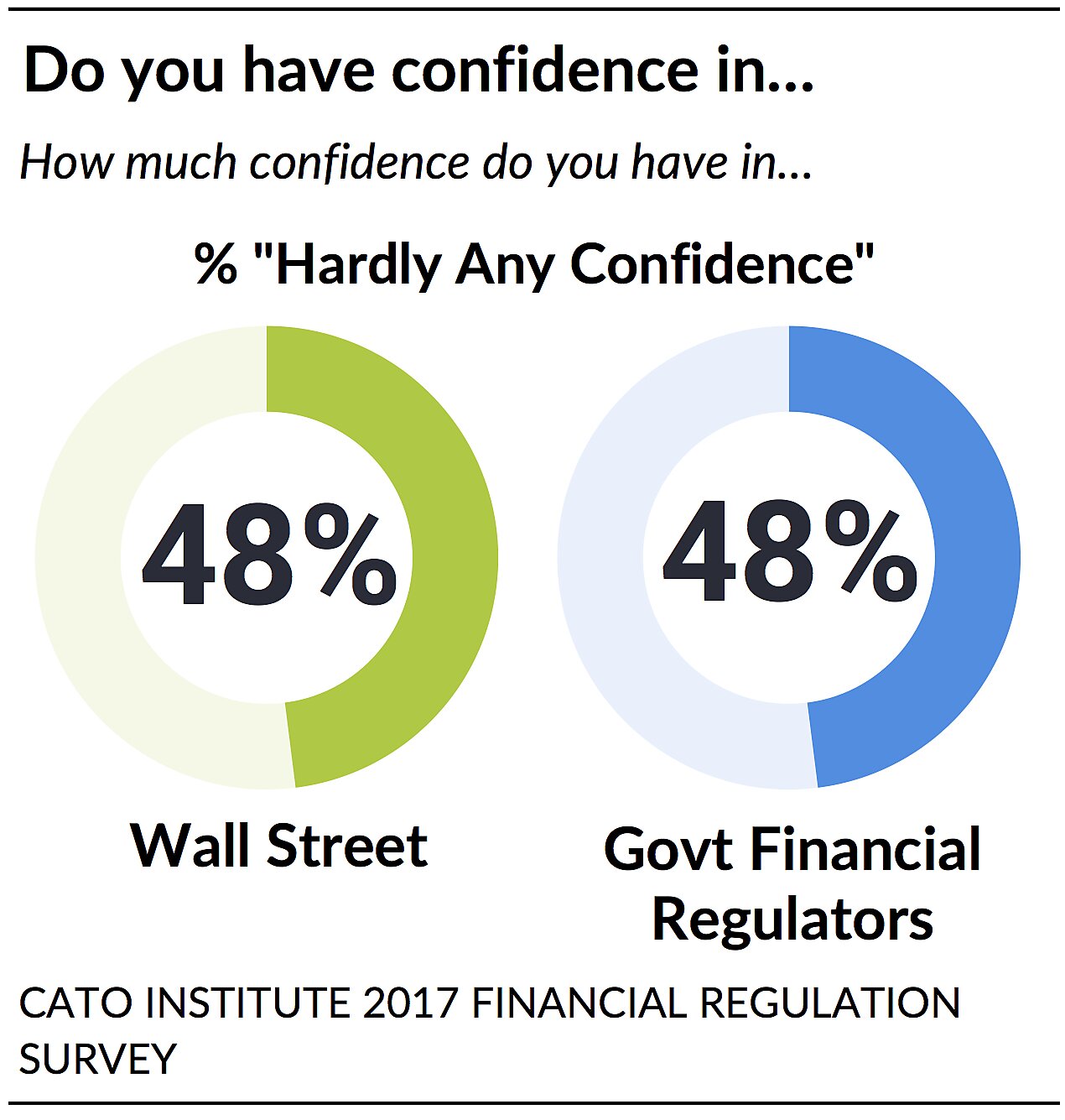

The new Cato Institute 2017 Financial Regulation national survey of 2,000 U.S. adults released today finds that Americans distrust government financial regulators as much as they distrust Wall Street. Nearly half (48%) have “hardly any confidence” in either.

Click here for full survey report

Americans have a love-hate relationship with regulators. Most believe regulators are ineffective, selfish, and biased:

- 74% of Americans believe regulations often fail to have their intended effect.

- 75% believe government financial regulators care more about their own jobs and ambitions than about the well-being of Americans.

- 80% think regulators allow political biases to impact their judgment.

But most also believe regulation can serve some important functions:

- 59% believe regulations, at least in the past, have produced positive benefits.

- 56% say regulations can help make businesses more responsive to people’s needs.

However, Americans do not think that regulators help banks make better business decisions (74%) or better decisions about how much risk to take (68%). Instead, Americans want regulators to focus on preventing banks and financial institutions from committing fraud (65%) and ensuring banks and financial institutions fulfill their obligations to customers (56%).

Americans Are Wary of Wall Street, But Believe It Is Essential

Nearly a decade after the 2008 financial crisis, Americans remain wary of Wall Street.

- 77% believe bankers would harm consumers if they thought they could make a lot of money doing so and get away with it.

- 64% think Wall Street bankers “get paid huge amounts of money” for “essentially tricking people.”

- Nearly half (49%) of Americans worry that corruption in the industry is “widespread” rather than limited to a few institutions.

At the same time, however, most Americans believe Wall Street serves an essential function in our economy.

- 64% believe Wall Street is “essential” because it provides the money businesses need to create jobs and develop new products.

- 59% believe Wall Street and financial institutions are important for helping develop life-saving technologies in medicine.

- 53% believe Wall Street is important for helping develop safety equipment in cars.

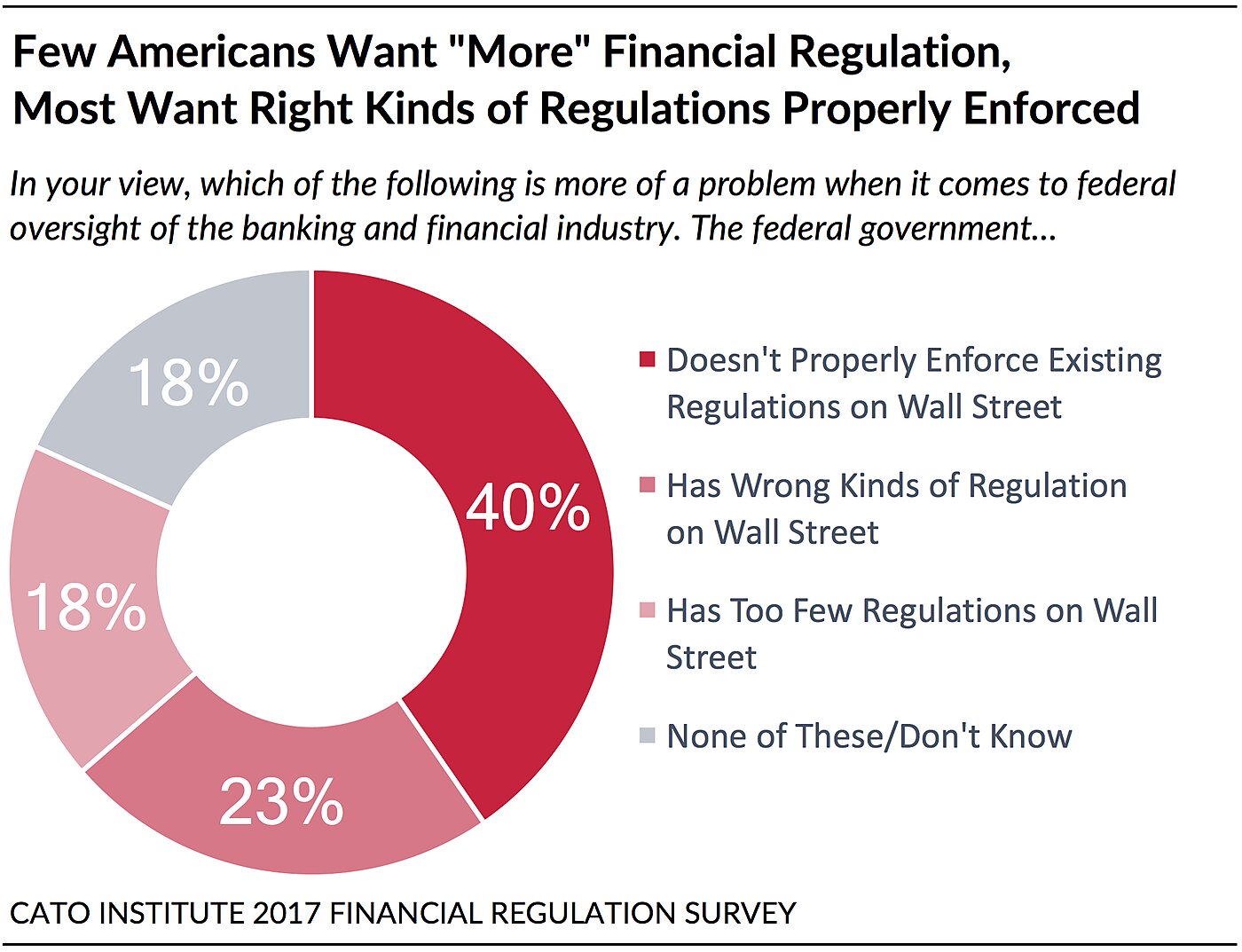

Few Americans Want “More” Financial Regulations—They Want the Right Kinds of Regulations, Properly Enforced

Polls routinely find that a plurality or majority of Americans want more oversight of Wall Street banks and financial institutions. This survey is no different. A plurality (41%) of Americans think more oversight of the financial industry is needed. However, only 18% think the problem with federal oversight of the banking industry is that there are “too few” rules on Wall Street. Instead, 63% say the government either fails to “properly enforce existing rules” (40%) or enacts the “wrong kinds” of regulations on big banks (23%).

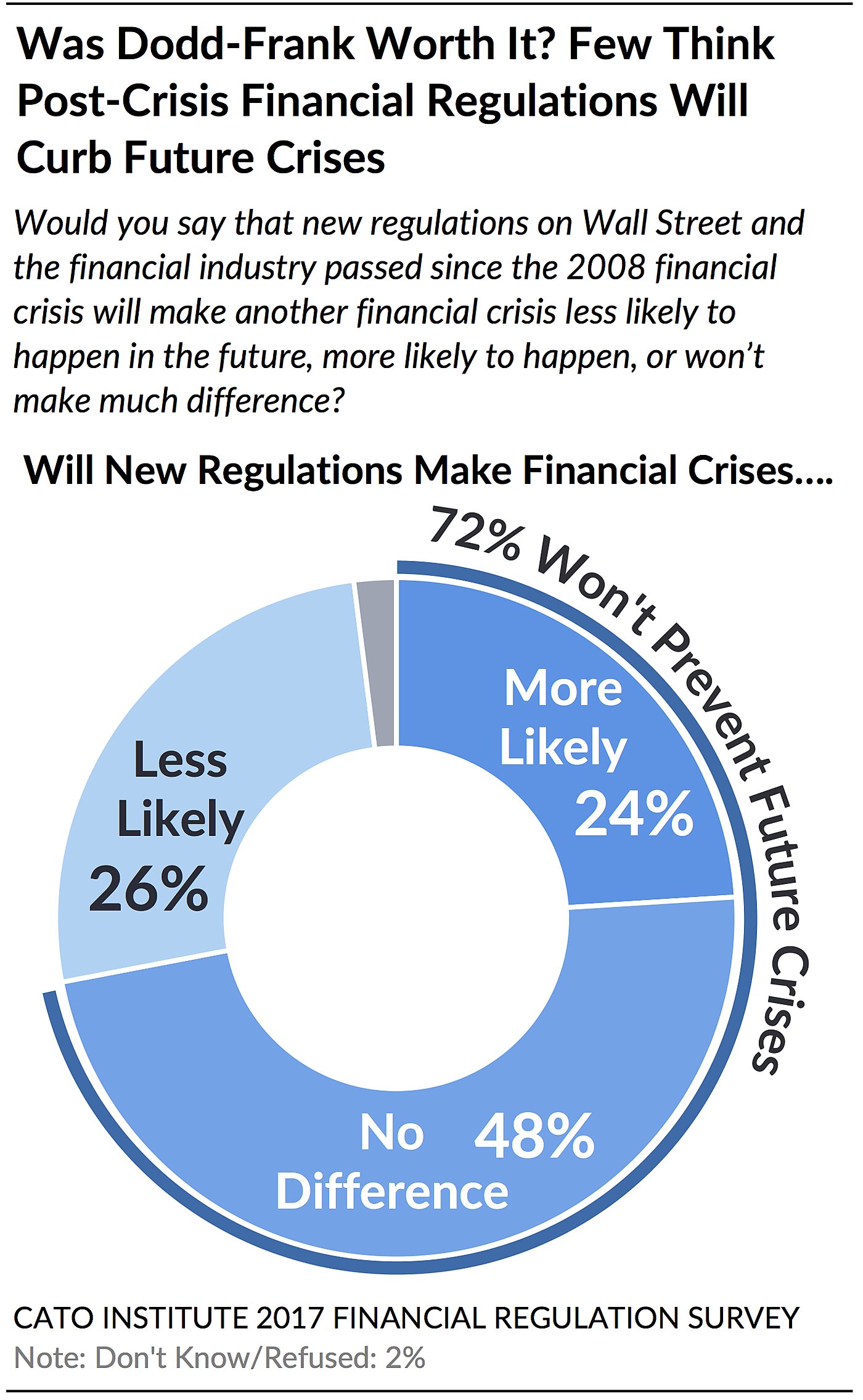

Most Are Skeptical Dodd-Frank Will Prevent Future Financial Crises

Will Dodd-Frank financial reforms work? Nearly three-fourths (72%) of Americans don’t believe that new regulations on Wall Street and the financial industry passed since the 2008 financial crisis will make future crises less likely. Just over a quarter (26%) believe such regulations will make future financial downturns less likely.

Americans Oppose Too Big to Fail

Americans reject the idea that some banks are so important to the U.S. economy that they should receive taxpayer dollars when facing bankruptcy. Instead, 65% say that “any bank and financial institution” should be allowed to fail if it can no longer meet its obligations. A third (32%), however, believe that some banks are too important to the U.S. financial system to be allowed to fail.

- Part of the reason most oppose the “Too Big to Fail” model may be that 60% believe that banks would make better financial decisions if they were convinced government would let them go out of business.

- Clinton voters (41%) are about twice as likely as Trump voters (20%) to believe some banks are too integral to the U.S. economy to fail. Libertarians are most opposed (81%) to bailing out banks.

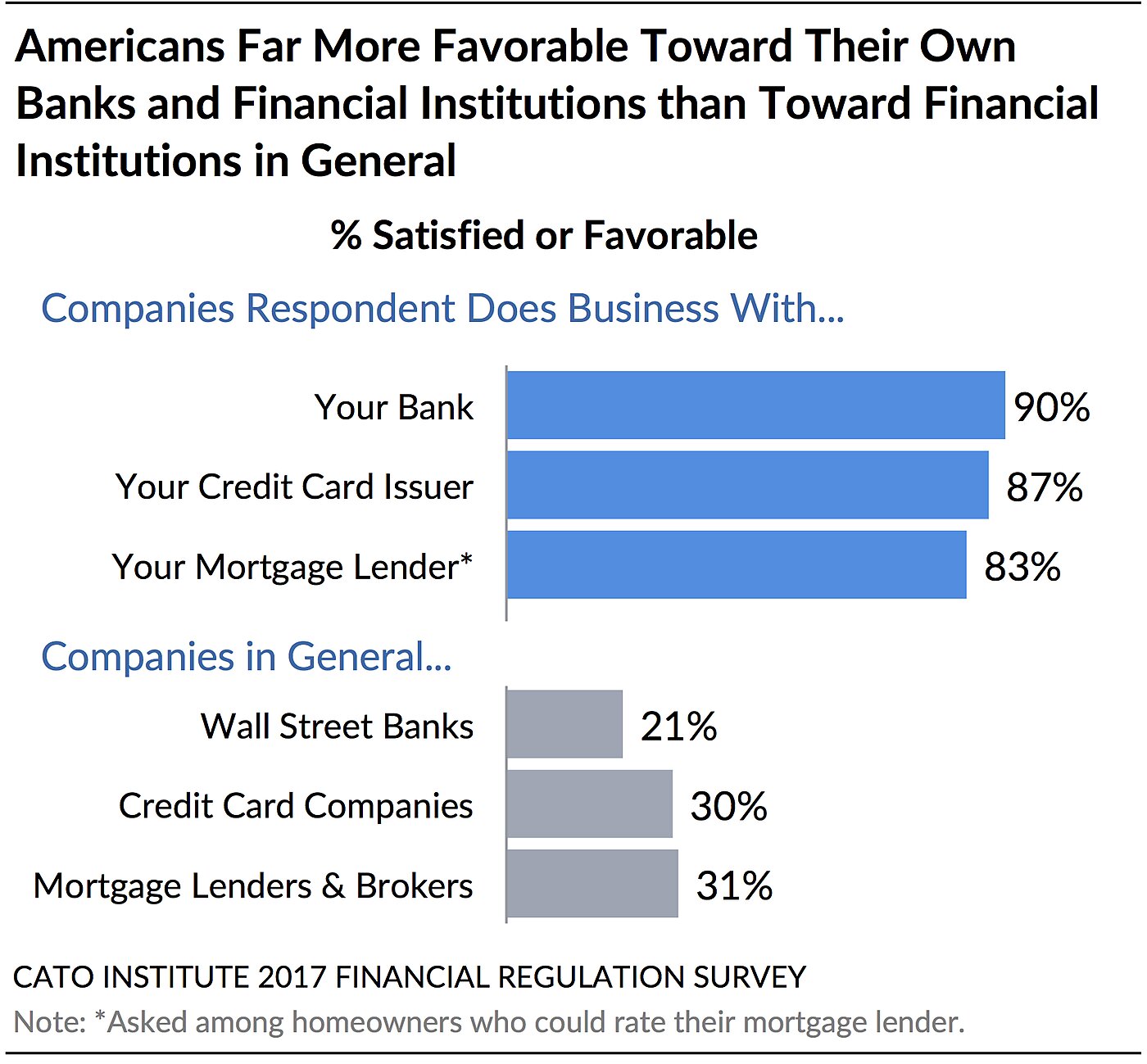

Despite Distrust of Wall Street, Americans Like Their Own Banks and Financial Institutions

- 90% are satisfied with their personal bank; 76% believe their bank has given them good information about the rates and risks associated with their account.

- 87% are satisfied with their credit card issuer; 81% believe their credit card issuer has given them good information about the rates, fees, and risks associated with their card.

- 83% are satisfied with their mortgage lender.

- Of those who have used payday or installment lenders in the past year, 63% believe the lender gave them good information about the fees and risks associated with the loan.[1]

Americans Want Regulators to Prioritize Fraud Protection, Ensure Banks Keep Promises

Financial regulators have a variety of tasks and goals. The public, however, believes that regulation should serve two primary functions: to protect consumers from fraud (65%) and to ensure banks fulfill obligations to their account holders (56%). Other initiatives such as restricting access to risky financial products (13%) is a priority among far fewer people.

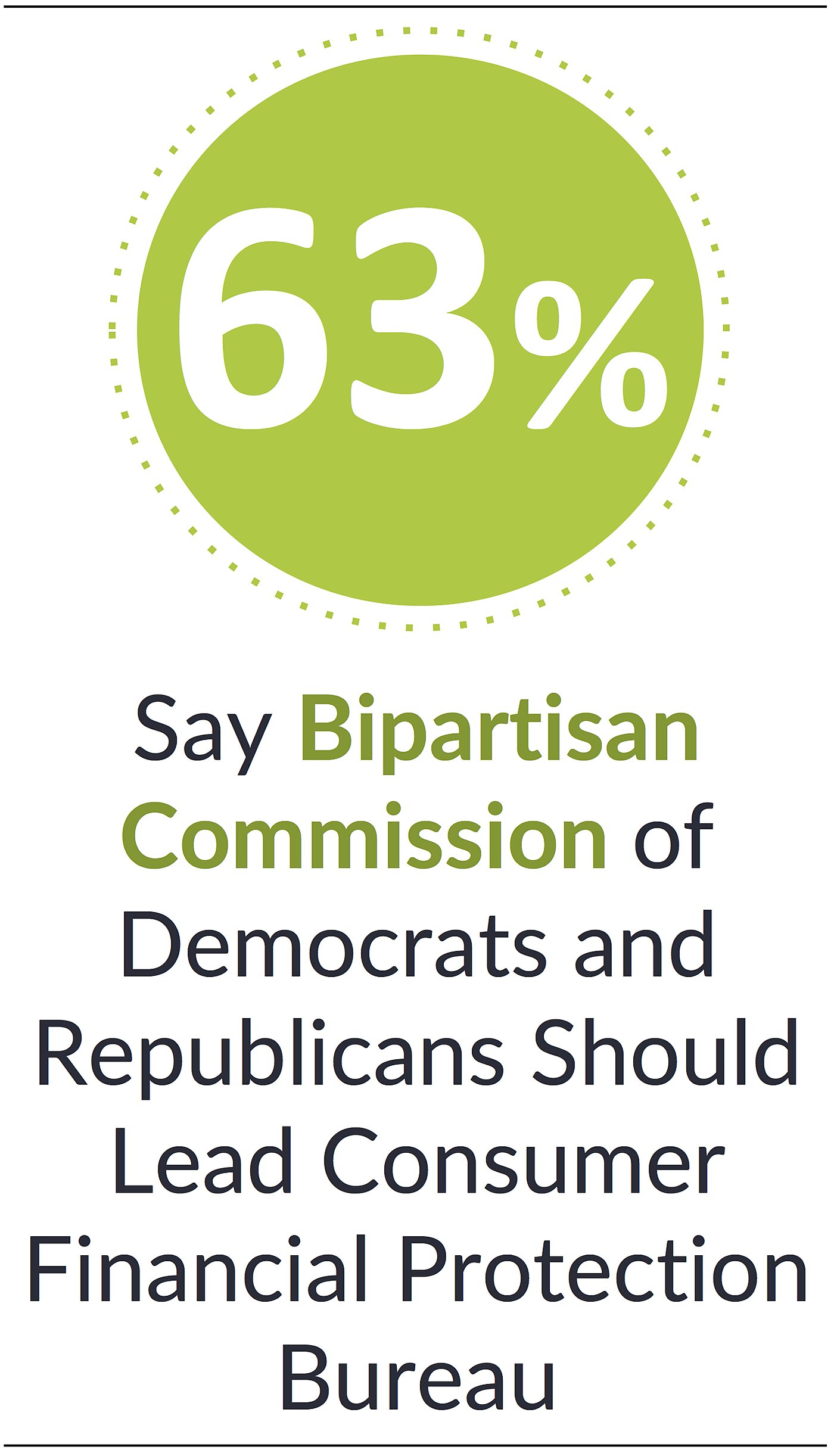

Democrats and Republicans Want a Bipartisan Commission to Run CFPB, Divided on CFPB Independence

- Most support changing the structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), a new federal agency created by Dodd-Frank in 2011. Nearly two-thirds (63%) of Americans think the CFPB should be run by a bipartisan commission of Democrats and Republicans, rather than by a single director. Support is post-partisan with 67% of Democrats and 64% of Republicans in favor of a bipartisan commission leading the agency.

- A majority (54%) of Americans think that Congress should not set the CFPB’s budget and should only have limited oversight of the agency. Given that only 7% of the country has confidence in Congress, these numbers are not surprising. A majority of Democrats (58%) support keeping the CFPB independent while a plurality of Republicans (50%) say Congress should closely oversee the new agency and set its budget.

- Few Americans (26%) believe the CFPB has achieved its mission to make the terms and conditions of credit cards and financial products easier to understand. Instead, 71% say that since the CFPB was created in 2011 credit card terms and conditions have not become easier to understand—including 54% who believe they have stayed the same and 17% who think they have become less clear.

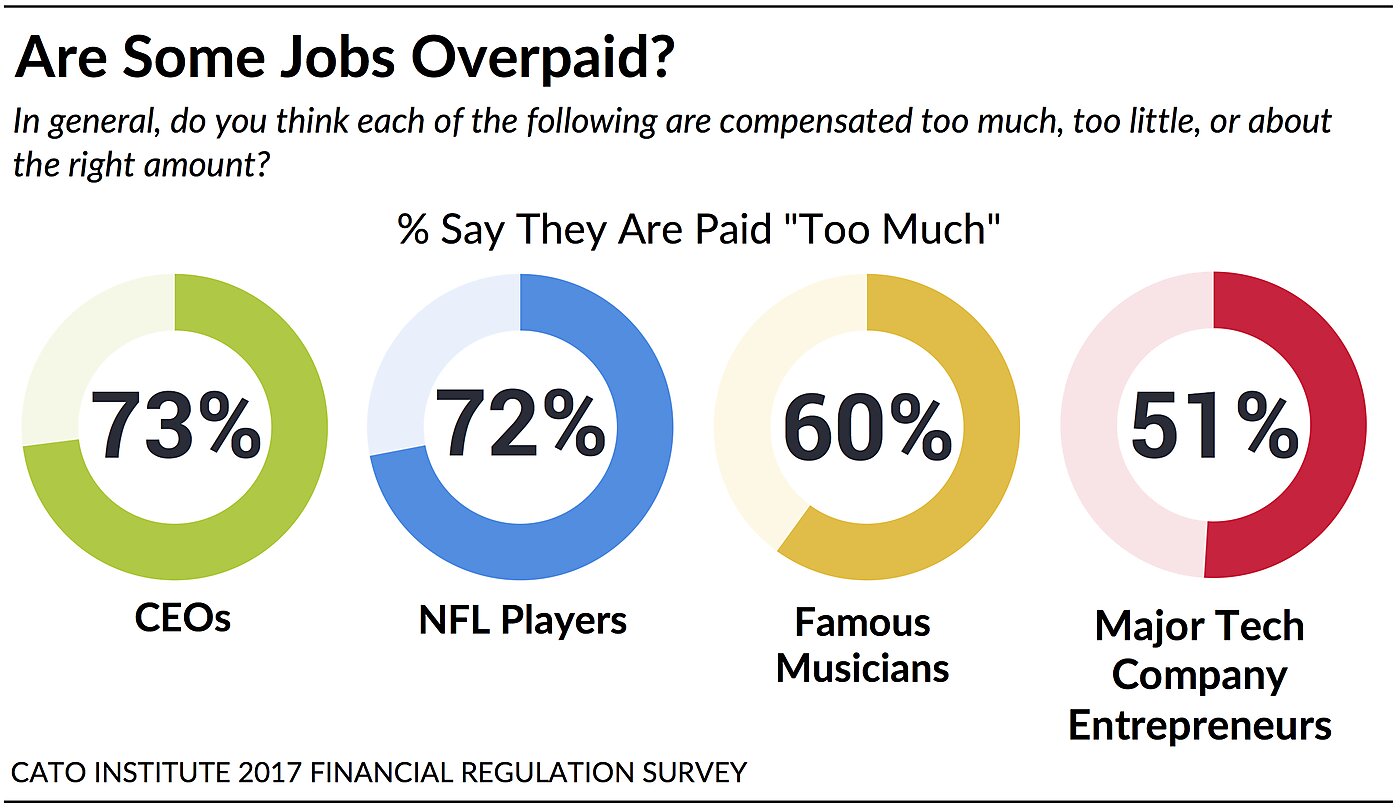

Americans as Likely to Say CEOs, NFL Football and NBA Basketball Players Are Overpaid, But Most Oppose Government Regulating Pay

Americans are about equally likely to think that CEOs (73%) and professional athletes like NBA players (74%) and NFL players (72%) are paid “too much.” Yet, the public doesn’t think the government ought to regulate the salaries of either corporate executives (53%) or professional athletes like NBA players (69%). Nonetheless, there is more support for regulating CEO pay (43%) than NBA salaries (28%).

Notably, compared to CEOs (73%) and NBA players (74%), far fewer believe that major tech company entrepreneurs are overpaid (51%).

Democrats support (56%) government regulating the salaries of CEOs but oppose regulating salaries of NBA players (66%) and famous actors (69%). In contrast, about 7 in 10 Republicans oppose government regulating the salaries of all three professions, even though they are more likely than Democrats to believe NBA players (60% vs. 47%) and famous actors (59% vs. 37%) are overpaid.

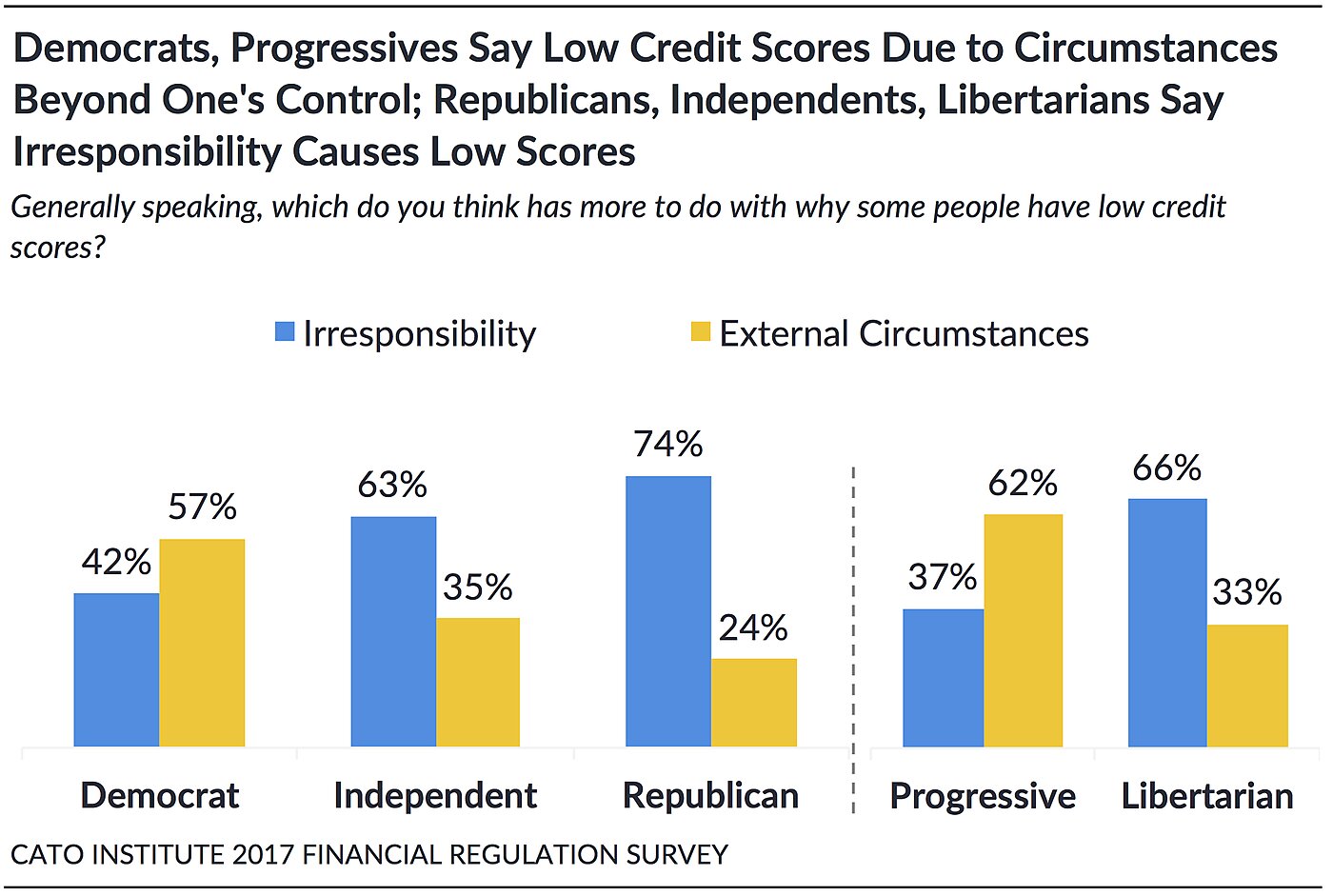

Most Support Risk-Based Pricing for Loans, Say Low Credit Scores are Due to Irresponsibility

Nearly three-fourths of Americans (74%) say they’d be “unwilling” to pay more for their home mortgage, car loan, or student loan to help those with low credit scores access these loans.

Americans may be unwilling to pay more to help those with low credit scores in part because a majority (58%) believe low credit scores are primarily due to irresponsibility, rather than circumstances beyond a person’s control (41%).

- Partisans sharply disagree about the cause of a low credit score. Most Democrats (57%) say low scores are primarily the result of “circumstances beyond [one’s] control” while 74% of Republicans and 63% of independents say “irresponsibility” is the primary cause.

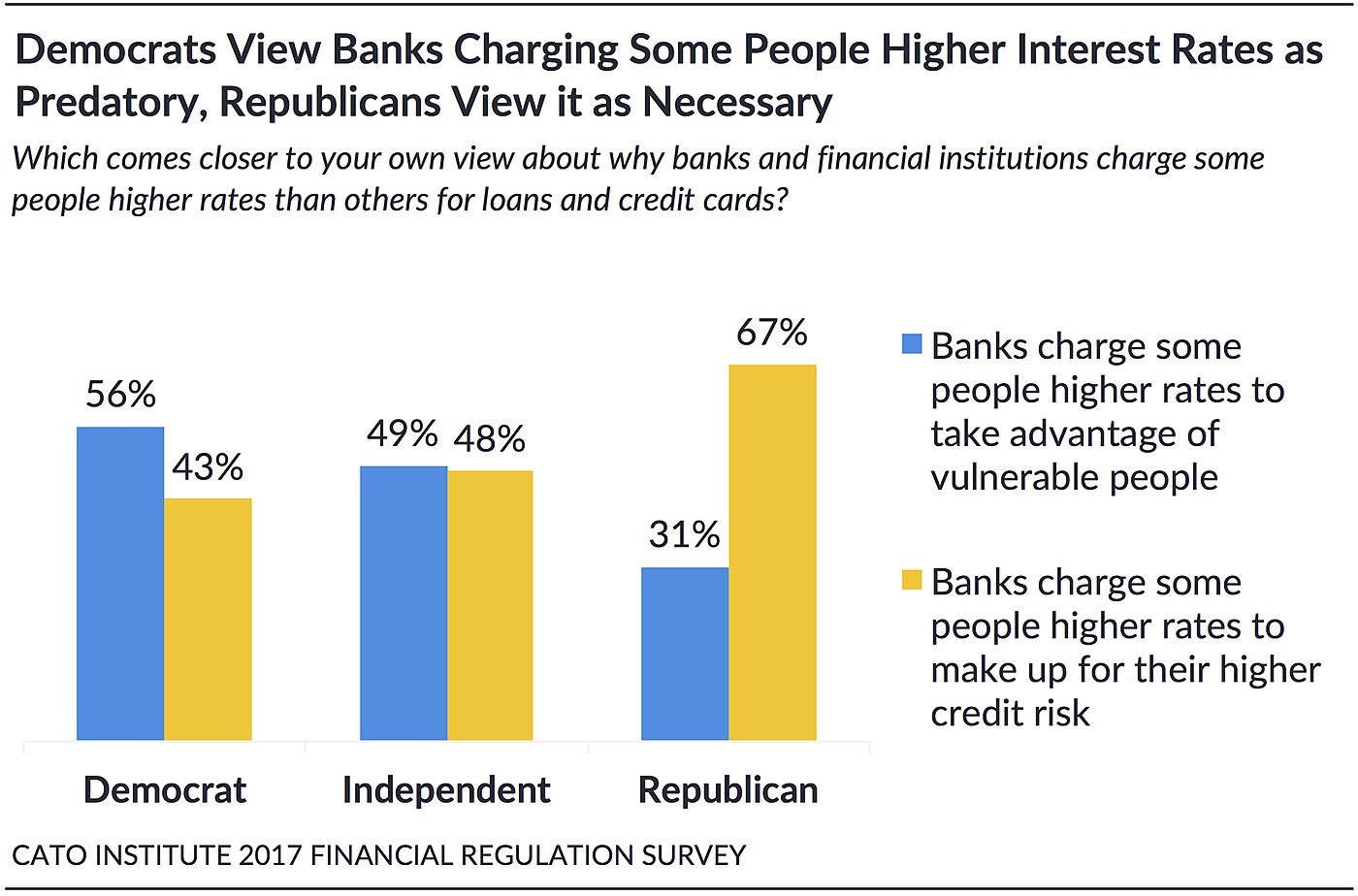

Americans are Unsure if Banks Charging Some People Higher Interest Rates is Justified or Predatory

A slim majority (52%) believe banks and financial institutions need to charge some people higher interest rates for loans and credit cards if those individuals present higher credit risks. Another 46% believe banks charge some people higher rates for loans in order to take advantage of those with few other options.

- Partisans disagree about why banks charge people different rates. A majority (56%) of Democrats believe lenders charge some people higher interest rates because they are predatory and take advantage of the vulnerable. In contrast, two-thirds (67%) of Republicans believe banks need to do this to compensate themselves for some borrowers’ greater credit risk.

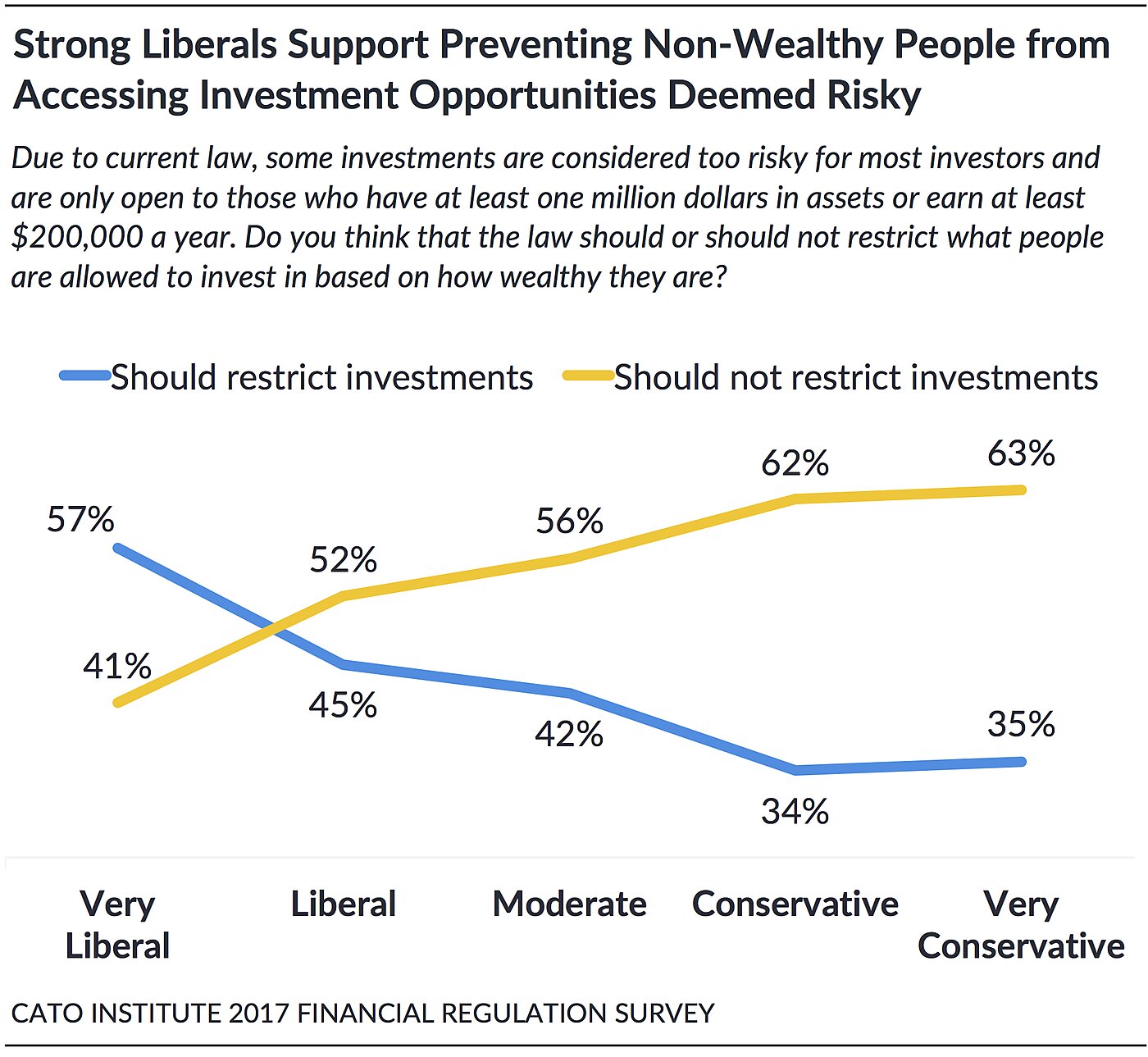

Most Oppose Accredited Investor Standard, Say Law Should Not Restrict Investment Options Based on Wealth

Due to current law, some investments are deemed too risky for the common investor and are only available to those with one million dollars in assets or who make $200,000 or more a year. However, a majority of Americans (58%) say the law should not restrict what people are allowed to invest in based on their wealth or income—even if the investments in question are risky. Thirty-nine percent (39%) think the law should restrict access to certain investments deemed risky.

- Strong liberals are unique in their support (57%) of government restricting access to risky investments based on a person’s wealth. Support drops to 45% among moderate liberals and to a third among conservatives.

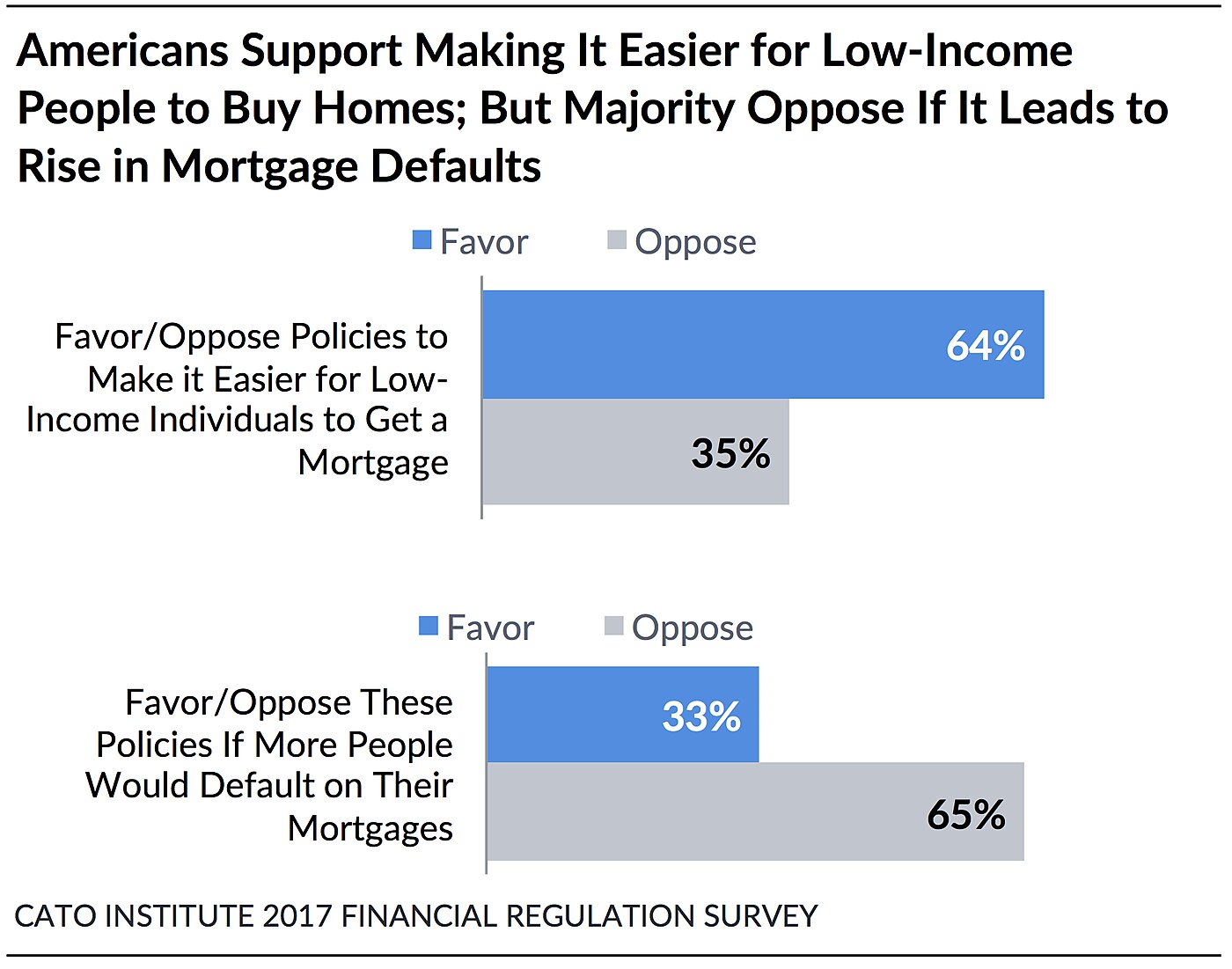

Most Support Helping Low-Income Families Own Homes Unless Policies Escalate Mortgage Defaults

Nearly two-thirds (64%) of the public support government policies intended to make it easier for low-income families to obtain a mortgage. However, a majority (66%) would oppose such policies if they resulted in more mortgage defaults and home foreclosures.

43% of Americans Would Pay for $500 Unexpected Expense with Savings

Less than half (43%) of Americans say they would pay for an unexpected $500 expense using money from savings or checking. The remainder would put the expense on a credit card (23%), ask family and friends for money (8%), sell something (7%), borrow the money from a bank or payday lender (5%), or simply not be able to pay it (12%).[2]

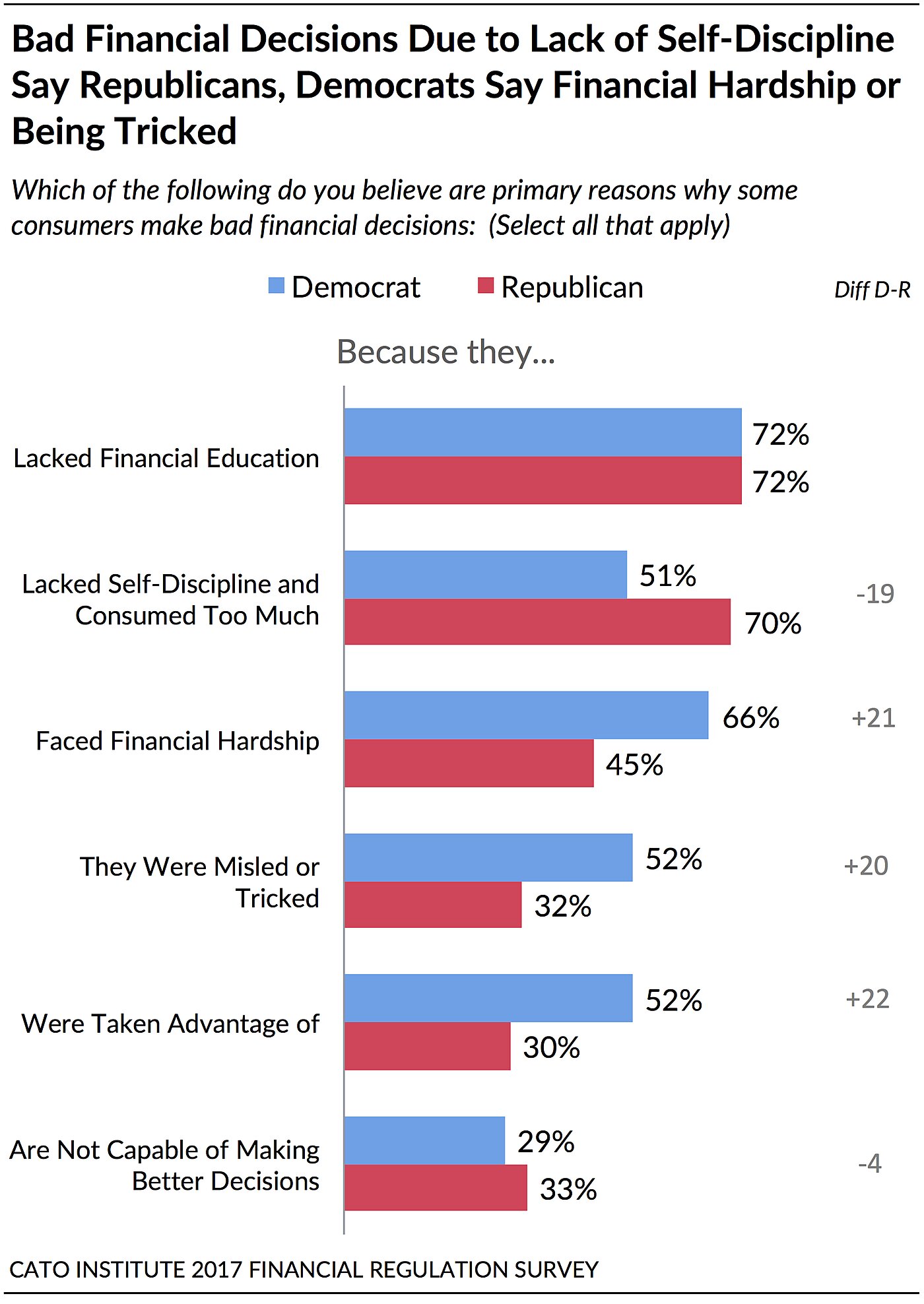

Most Say Bad Financial Decisionmaking Due to Lack of Financial Education and Self-Discipline

The public says the top three reasons consumers make bad financial decisions include lacking financial education (70%), lacking self-discipline (60%), and facing financial hardship (54%). Less than half say that consumers being “misled or tricked” (43%), taken advantage of (42%), or incapable (30%) are primary causes.

- Both Democrats (72%) and Republicans (72%) agree that a lack of financial education is key.

- Republicans (70%) are nearly 20 points more likely than Democrats (51%) to say that a lack of self-discipline is a primary reason for unwise decisionmaking.

- Democrats are roughly 20 points more likely than Republicans to say that poor financial decisionmaking is due to external circumstances such as financial hardship (66% vs. 45%), being tricked (52% vs. 32%), or being taken advantage of (52% vs. 30%).

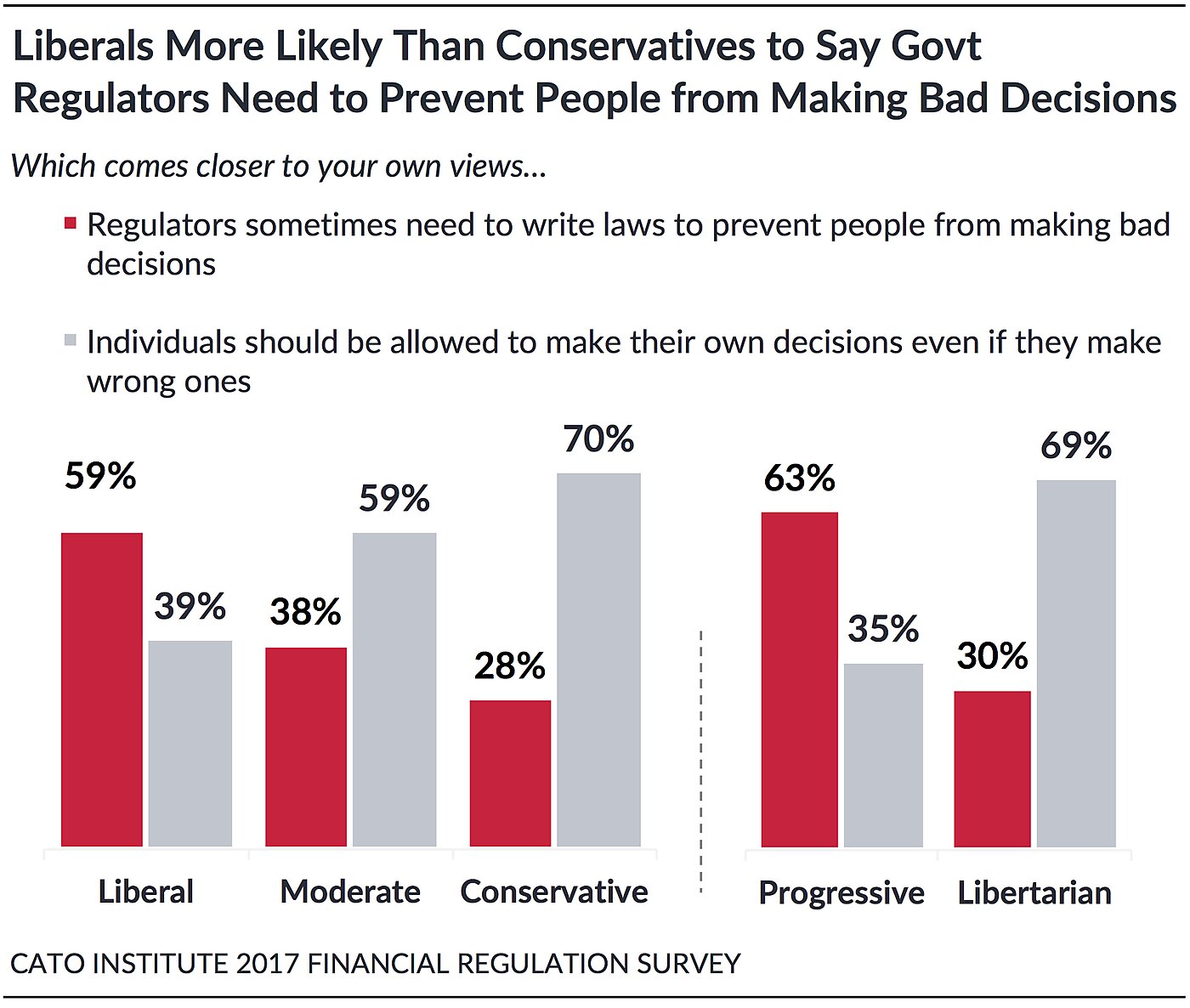

Most Say Government Should Allow Individuals to Make Their Own Financial Decisions—Even If They Make the Wrong Ones

When it comes to promoting and managing consumers’ financial health, most believe (58%) that individuals “should be allowed to make their own decisions even if they make the wrong ones.” However, 4 in 10 say that sometimes government regulators “need to write laws that prevent people from making bad decisions.”

- A majority of Democrats (57%) believe that sometimes regulators need to write laws that protect people from making bad decisions

- Majorities of Republicans (73%) and independents (69%) don’t think government should restrict people’s financial choices to protect them.

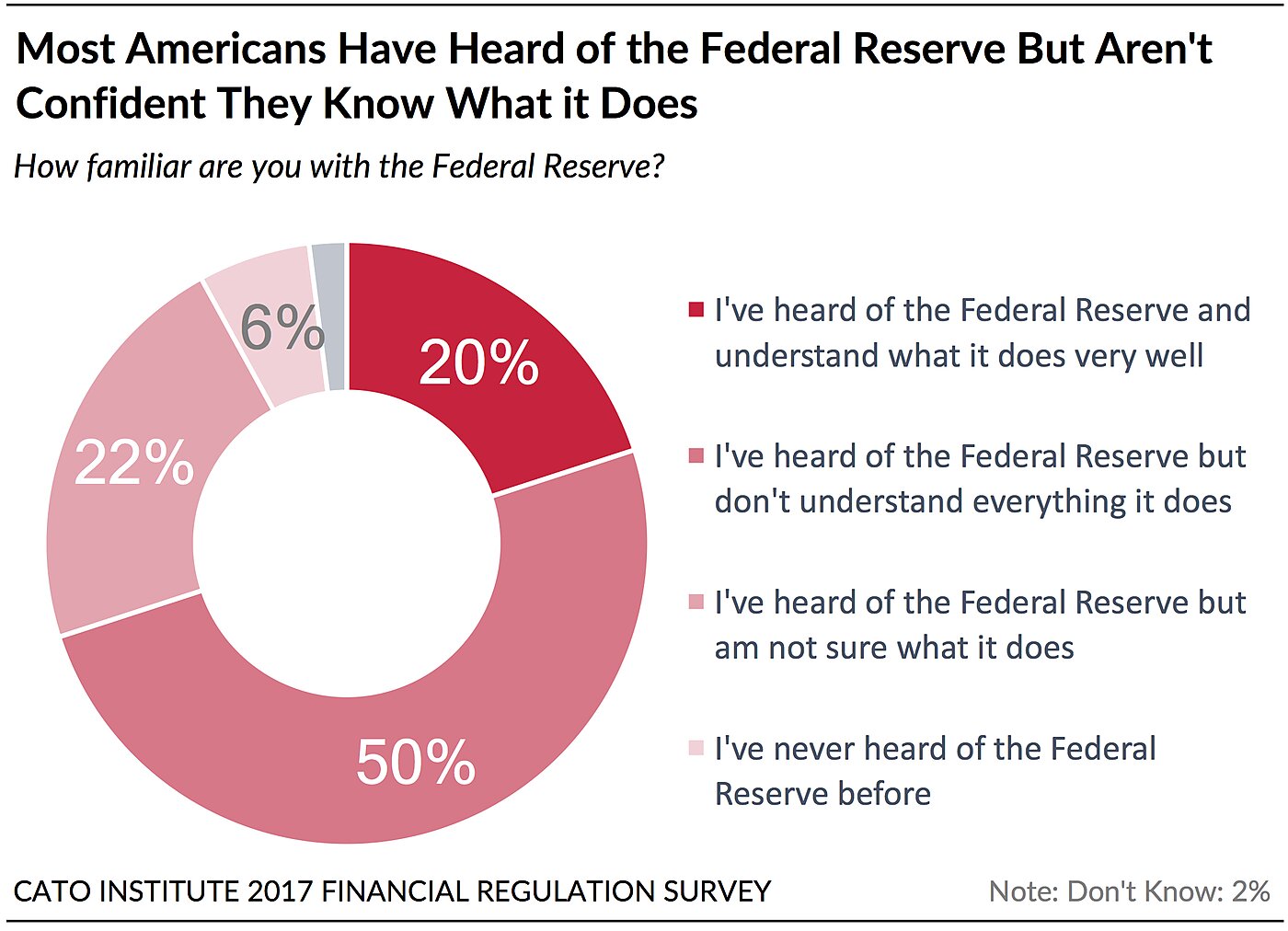

Few Americans Know a Lot about the Federal Reserve; Among Those Informed, the Fed Polarizes Partisans

- Only 20% of Americans say they have heard of the Federal Reserve and understand what it does very well. Half (50%) have heard of the Fed but don’t understand everything it does; 22% have heard of the Fed but don’t know what it does while 6% have never heard of it.

- Tea Partiers (67%), libertarians (57%) and conservatives (50%) are about three times as likely as liberals (19%) to say the Fed has “too much power.”

- Pluralities of libertarians (50%) and strong conservatives (50%) believe the Fed helped cause the 2008 financial crisis. In contrast, a plurality of liberals (43%) believe the Fed cut the crisis short.

- Among those with an opinion, 68% of Democrats want Federal Reserve officials to primarily determine interest rates in the economy. Conversely, 74% of Republicans want the free-market system to do this.

Click here for full poll results and methodological information

Sign up here to receive forthcoming Cato Institute survey reports

The Cato Institute 2017 Financial Regulation Survey was designed and conducted by the Cato Institute in collaboration with YouGov. YouGov collected responses online May 24–31, 2017 from a national sample of 2,000 Americans 18 years of age and older. Restrictions are put in place to ensure that only the people selected and contacted by YouGov are allowed to participate. The margin of error for the survey is +/- 2.17 percentage points at the 95% level of confidence.

USA Today on Tax Reform

On the topic of tax reform, I wrote the “opposing view” column yesterday for USA Today. But rather than oppose the newspaper’s editors, I agree with most of their views.

The editors said:

The federal tax code is an unholy mess. It consumes 6 billion hours of Americans’ time each year. It coddles politically entrenched industries. And it burdens America’s blue-chip corporations in their bid to compete with overseas rivals.”

“Some taxes should be cut. The corporate income tax of 35%, for instance, should be set at 20% or lower, with a lot fewer loopholes. The current rate gives an advantage to companies not headquartered in the United States. And its complexity encourages all manner of tax gamesmanship.

Exactly!

The editors continued:

At the same time, everyday Americans need to confront the fact that their rates are far higher than they need be thanks to massive—and highly popular—deductions for such expenditures as mortgage interest, health care, charitable gifts and state and local taxes.

Of these, only the charitable gifts break has a strong case for being left alone. The tax-free status of health plans needs a limit. The deductions for mortgage interest and state and local taxes should be gradually phased out or capped, as they have perverse effects.

I agree with that too. Leave the charity deduction alone, cut or eliminate the mortgage interest and state and local tax deductions, and cap the health insurance exclusion.

My article said that if Republicans cannot agree on substantial offsets to rate reductions, “they should scale back their tax package to just the most pro-growth elements, particularly a corporate tax rate cut.” If the GOP focuses on growth-generating reforms, the deficit may increase in the short term, but the tax base would expand over time offsetting the initial budgetary effect.

The important thing is that America’s businesses and their workers desperately need a more competitive tax code. The Republicans have a rare chance right now to get it done.

Related Tags

Reversible Lanes, Not Trains

In the days before Hurricane Irma made landfall in Florida, the state ordered 6.3 million people to leave their homes. As people in the rest of the nation watched videos and photos of bumper-to-bumper northbound traffic on Interstates 75 and 95, while the southbound lanes were nearly empty, most had one of two reactions. Some said, “If only Florida had large-scale passenger train service that could move those people out,” while others asked, “Why aren’t people allowed to drive north on the empty southbound lanes?”

The aftermath of the storm has already opened a debate over what Florida should do to increase its resilience in the future: build more roads or build more rail lines. The right answer is neither: instead, state transportation departments in Florida and elsewhere need to develop emergency plans to make better use of the transportation resources they already have.

Rail advocates like to claim that rail lines have much higher capacities for moving people than roads, but that’s simply not true. After the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, the Southern Pacific Railroad moved 300,000 people–free of charge–out of the city in what was probably the largest mass transportation evacuation in American history. While impressive, it took the railroad five days to move all of those people on three different routes. Even accounting for improvements in rail capacities in the last century, moving 6 million people out of south Florida by rail would take weeks, not the four days available between Florida’s first evacuation orders and the arrival of Hurricane Irma.

At the same time, the state of Florida could have done more to relieve congestion on major evacuation routes. The most it did was to allow vehicles to use the left shoulder lanes on part of I‑75 and part of I‑4 (which isn’t even a north-south route), but not, so far as I can tell, on I‑95. What the state should have done, since there was very little southbound traffic, was to open up all but one of the southbound lanes of I‑75 and I‑75 to northbound traffic.

A typical four-lane freeway has wide shoulders on both left and right sides of each of the two pairs of lanes. The opposing lanes are often separated by concrete barriers called Jersey Barriers that are designed to be easy to move. The state could have moved a few dozen of those barriers in strategic locations to give northbound traffic access to the southbound lanes. The state could also have put up plastic pylons to separate the north- and southbound traffic in what are normally the south-bound lanes. States take these actions all the time for road construction.

In the case of a four-lane freeway, opening one southbound lane and both center shoulders to northbound traffic would turn two northbound lanes into five. For six-lane freeways, this would turn three northbound lanes into seven. In both cases, there would still be one lane for southbound traffic and the outside shoulders for emergency vehicles. The leaders of every state highway bureau that doesn’t have an evacuation plan reversing some lanes to the prevailing direction of travel should be ashamed of themselves.

Successful private businesses respond rapidly and flexibly to changes in the market. Only the government would say, “Look: travel demand is changing dramatically. Let’s do absolutely nothing about it.”

Rail advocates argue that trains are more egalitarian because not everyone can afford to own a car. In particular, Florida’s older population supposedly meant that fewer than the average number of households have cars. In fact, data from the 2016 American Community Survey indicates that Florida households are more likely to have cars than the national average: 93.4 percent of Florida households have at least one car compared with 91.3 percent nationwide.

The reality is that passenger trains are far more expensive to operate per passenger mile than cars. Amtrak fares average nearly 30 cents a passenger mile and subsidies to Amtrak are another 25 cents a passenger mile. Americans spend an average of about 24 cents a passenger mile driving and those who wish can spend a lot less by buying used cars instead of new. Highway subsidies add only another penny or so. For daily transportation, this makes trains the elitist form of travel while cars are more egalitarian.

Nor do trains offer better service in the event of natural disasters. Tri-Rail, south Florida’s commuter-rail line, shut down 60 hours before Irma hit so employees could tie down trains and facilities for the storm. Amtrak cancelled its Florida trains at the same time as Tri-Rail.

After the storm, it took Tri-Rail almost five days to clear the tracks of fallen trees and restore power to its electric trains. One part of the rail line was so damaged that the agency is busing people around that part of the line. As of this writing, Amtrak is still not running trains south of Jacksonville.

Using trains to evacuate people after a sudden natural disaster such as an earthquake is even more problematic than before the event. Rail infrastructure, especially for fast trains, requires a high level of precision that is not needed for highways. Vehicles on pavement are far more resilient than trains on inflexible tracks since pavement doesn’t have to be as smooth as tracks. Unlike trains, highway vehicles can drive around obstacles that are partly blocking roads and by-pass roads that are completely blocked.

Natural disasters are going to happen. Eastern and Southern coastal states suffer from hurricanes. The Midwest has tornadoes. The West Coast has earthquakes and the occasional volcanic eruption. What America needs to respond to these events is not more trains but more creative and flexible highway management.

Related Tags

Will Senate Debate AUMF This Year? Sen. Flake Thinks So

Earlier this week, Sen. Rand Paul put forth an amendment that would sunset the 2001 AUMF and 2002 Iraq AUMF after 6‑months. Somewhat unsurprisingly, the amendment was defeated as nearly all Senate Republicans (and a handful of Democrats) voted to strike it down.

As I looked through the roll call, however, I was surprised by the vote of one Senator in particular: Jeff Flake. In 2015 and again this year, Flake, along with Tim Kaine of Virginia, introduced legislation for a new AUMF. Yet, Flake voted to table (i.e. kill) Paul’s amendment.

Why would a Senator who clearly wants a new AUMF vote against this measure?

I wouldn’t have to wait long for an answer. Yesterday, I attended a “Conversation with Senator Jeff Flake,” hosted by the Council on Foreign Relations, and was able to ask the Senator directly about the rationale behind his recent vote. Here is an excerpt from Sen. Flake’s response:

I didn’t support the Paul amendment because I’m trying to be a stickler for regular order. And when we have an opportunity to actually move something through in regular order, that’s what I’d like to do. And it is proper for this bill—we have had a hearing on it already—the next move would be a markup to actually amend it and…it will be a bipartisan bill that will move. I spoke to Chairman Corker… just yesterday, and got a commitment that this bill is going to move. So I’m confident that it will. Had I not been confident, then I would have voted for the forcing mechanism.

His justification has merit. And I hope that he is correct, and that Chairman Corker moves on AUMF legislation in the coming months. But if that fails to happen, and Sen. Paul again offers his amendment, Senator Flake is now on record that he would support it.

You can see my exchange with Senator Flake in full here.