It turns out you can still buy a 20 oz. sweetened beverage in Mayor Bloomberg’s New York. And guess whose municipal coffers you’re benefiting when you do? Ira Stoll has details. Earlier podcast here.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

General

George Will Quotes Cato Study Showing IPAB Is Even Worse than Romney Says

In Wednesday night’s presidential debate, Mitt Romney claimed that ObamaCare’s Independent Payment Advisory Board is “an unelected board that’s going to tell people ultimately what kind of treatments they can have.”

President Obama officially denies it, yet he confirmed Romney’s claim when he said, “what this board does is basically identifies best practices and says, let’s use the purchasing power of Medicare and Medicaid to help to institutionalize all these good things that we do.”

In this excerpt from his column in today’s The Washington Post, George F. Will quotes my coauthor Diane Cohen and me to show that IPAB is even worse than Romney claimed:

The Independent Payment Advisory Board perfectly illustrates liberalism’s itch to remove choices from individuals, and from their elected representatives, and to repose the power to choose in supposed experts liberated from democratic accountability.Beginning in 2014, IPAB would consist of 15 unelected technocrats whose recommendations for reducing Medicare costs must be enacted by Congress by Aug. 15 of each year. If Congress does not enact them, or other measures achieving the same level of cost containment, IPAB’s proposals automatically are transformed from recommendations into law. Without being approved by Congress. Without being signed by the president.

These facts refute Obama’s Denver assurance that IPAB “can’t make decisions about what treatments are given.” It can and will by controlling payments to doctors and hospitals. Hence the emptiness of Obamacare’s language that IPAB’s proposals “shall not include any recommendation to ration health care.”

By Obamacare’s terms, Congress can repeal IPAB only during a seven-month window in 2017, and then only by three-fifths majorities in both chambers. After that, the law precludes Congress from ever altering IPAB proposals.

Because IPAB effectively makes law, thereby traducing the separation of powers, and entrenches IPAB in a manner that derogates the powers of future Congresses, it has been well described by a Cato Institute study as “the most anti-constitutional measure ever to pass Congress.”

Our paper is titled, “The Independent Payment Advisory Board: PPACA’s Anti-Constitutional and Authoritarian Super-Legislature.” It broke the news that, as Will writes, ObamaCare “precludes Congress from ever altering IPAB proposals” after 2017.

Related Tags

How Much ‘Compassion’ Is Really Just Posturing?

Magatte Wade, a Senegalese-American businesswoman in New York, writes in The Guardian:

Last Saturday I spoke at the Harvard Women in Business Conference, an annual event that I love…

Later, during a discussion on Going Global, a young woman asked, “For the Americans on the panel, how do you deal with being a person of privilege while working in global development?” My eyes lit up with fury as she directed her question specifically at the white Americans on the panel. I let them answer, then smiled and added with a wink: “I am an American, you know, and also a person of privilege.” She instantly understood what I meant.

Her question assumed that those of us in developing nations are to be pitied…

For many of those who “care” about Africans, we are objects through which they express their own “caring”.

To drive the point home, Wade posts this excellent video of “actor Djimon Hounsou perform[ing] a powerful rendition of Binyavanga Wainaina’s piece How Not to Write About Africa.”

(NB: The title of the original article appears to be “How to Write about Africa,” without the “Not.”)

It runs both ways. In Replacing ObamaCare, I discuss how “the act of expressing pity for uninsured Americans allows Rwandan elites to signal something about themselves (‘We are compassionate!’). ” Also:

My hunch is that this is an under-appreciated reason why some people support universal coverage: a government guarantee of health insurance coverage provides its supporters psychic benefits — even if it does not improve health or financial security, and maybe even if both health and financial security suffer.

Or as Charles Murray puts it: “The tax checks we write buy us, for relatively little money and no effort at all, a quieted conscience. The more we pay, the more certain we can be that we have done our part, and it is essential that we feel that way regardless of what we accomplish.”

Related Tags

Romney and Obama on the Role of Government

President Obama and Mitt Romney effectively delivered clashing statements on the role of government last night. That’s an issue I discuss in the latest issue of Reason, in a review of two new books, To Promote the General Welfare: The Case for Big Government, edited by Steven Conn, and Our Divided Political Heart: The Battle for the American Idea in an Age of Discontent, by E. J. Dionne, Jr. It’s not online yet, so you’ll have to go to the newsstand to buy a copy! Obama seemed to be channeling the Conn book, with its endless repetition of “things the government did for us”:

I also believe that government has the capacity — the federal government has the capacity to help open up opportunity and create ladders of opportunity and to create frameworks where the American people can succeed. Look, the genius of America is the free enterprise system, and freedom, and the fact that people can go out there and start a business, work on an idea, make their own decisions.

But as Abraham Lincoln understood, there are also some things we do better together.

So in the middle of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln said, let’s help to finance the Transcontinental Railroad. Let’s start the National Academy of Sciences. Let’s start land grant colleges, because we want to give these gateways of opportunity for all Americans, because if all Americans are getting opportunity, we’re all going to be better off. That doesn’t restrict people’s freedom; that enhances it.

And so what I’ve tried to do as president is to apply those same principles.

Romney had a different view:

The role of government — look behind us: the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.

The role of government is to promote and protect the principles of those documents. First, life and liberty. We have a responsibility to protect the lives and liberties of our people, and that means the military, second to none. I do not believe in cutting our military. I believe in maintaining the strength of America’s military.

Second, in that line that says, we are endowed by our Creator with our rights — I believe we must maintain our commitment to religious tolerance and freedom in this country. That statement also says that we are endowed by our Creator with the right to pursue happiness as we choose. I interpret that as, one, making sure that those people who are less fortunate and can’t care for themselves are cared by — by one another.

We’re a nation that believes we’re all children of the same God. And we care for those that have difficulties — those that are elderly and have problems and challenges, those that disabled, we care for them. And we look for discovery and innovation, all these thing desired out of the American heart to provide the pursuit of happiness for our citizens.

But we also believe in maintaining for individuals the right to pursue their dreams, and not to have the government substitute itself for the rights of free individuals. And what we’re seeing right now is, in my view, a — a trickle-down government approach which has government thinking it can do a better job than free people pursuing their dreams. And it’s not working.

His rhetoric was certainly more appealing to libertarian voters. But when Romney waxes eloquent about freedom, the rubber rarely meets the road. He’s the father of the health care mandate. His view of liberty, above, is a strong military. His closing argument, about the candidates’ “two very different paths,” ended with a promise not to cut Medicare or the military. He promised to deliver “energy independence” and to crack down on countries that sell us goods.

More on why libertarians are skeptical about big government here — and in Reason!

Related Tags

The Tax Policy Center’s $5 Trillion Blunder: “Nonpartisan” nonsense

In “The $5 Trillion Question: How Big Is Romney’s Cut” Wall Street Journal reporters Damlan Paletta and John D. McKinnon echo, once again, the journalistic convention of contrasting “the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center” with “the conservative American Enterprise Institute.” In the English language, the opposite of “conservative” is not “nonpartisan.” On the contrary, the phrase “nonpartisan” applies equally to the American Enterprise Institute (or Cato Institute) as it does to Tax Policy Center (TPC) — a front for the Brookings Institution and Urban Institute. To be “nonpartisan” does not mean non-ideological, unbiased or even competent. It simply means following a few rules so the IRS will allow the organization to receive tax-deductible contributions. Governor Romney wants to severely curb such deductions (including his own), which does not necessarily make the TPC a disinterested observer, even if there really were one or two closet Republicans (or even non-Keynesians) at the TPC.

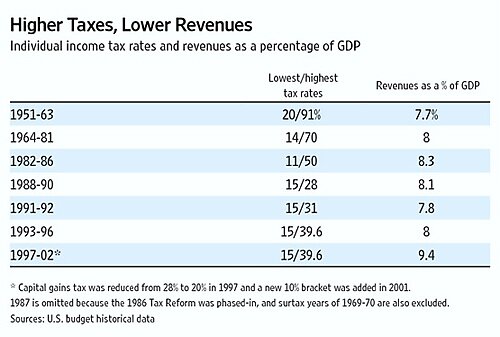

The U.S. already cut marginal tax rates across-the-board by more than 20 percent in 1964 and 1984 (the 1981 law, like that of 2001, was foolishly phased-in). In both cases, the Table shows that revenues from the individual income tax were higher than before, as a share of GDP. The economy grew much faster too, raising payroll and corporate tax receipts. Until the TPC can explain how and why that happened, they cannot even pretend to predict that Romney’s more modest tax reform will lose any revenue, much less $5 trillion. Incidentally, deductions were not significantly curbed in the tax laws of 1964 or 1981, or in the Tax Reform of 1986 (which merely substituted reduced itemized deductions for a much larger standard deduction). If Romney puts a cap on deductions, either as a percentage of AGI or as a dollar limit, the net effect of his plan would raise revenues, particularly from people like Warren Buffett and Mitt Romney (who deduct millions in charitable contributions).

The Tax Policy Center’s fundamental error is to assume no behavioral response at all to lower tax rates – an “elasticity of taxable income” (ETI) of zero. The academic evidence is that ETI is at least 0.4 for all taxpayers, as Martin Feldstein observed, mostly because ETI is above 1.0 for the top 1 percent, as I recently explained in the Journal. Cut top rates and the rich report more income; raise top rates and much of their income disappears — through reduced economic activity and increased avoidance.

Related Tags

Post-Debate Analysis: Debunking Obama’s Flawed Assertions on Tax Deductions and Corporate Welfare

In a violation of the 8th Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment, my brutal overseers at the Cato Institute required me to watch last night’s debate (you can see what Cato scholars said by clicking here).

But I will admit that it was good to see Obama finally put on the defensive, something that almost never happens since the press protects him (with one key exception, as shown in this cartoon).

This doesn’t mean I like Romney, who would probably be another Bush if he got to the White House.

On the specifics, I obviously didn’t like Obama’s predictable push for class warfare tax policy, but I’ve addressed that issue often enough that I don’t have anything new to add.

I was irked, though, by Obama’s illiteracy on the matter of business deductions for corporate jets, oil companies, and firms that “ship jobs overseas.”

Let’s start by reiterating what I wrote last year about how to define corporate income: At the risk of stating the obvious, profit is total revenues minus total costs. Unfortunately, that’s not how the corporate tax system works.

Sometimes the government allows a company to have special tax breaks that reduce tax liabilities (such as the ethanol credit) and sometimes the government makes a company overstate its profits by not allowing it to fully deduct costs.

During the debate, Obama was endorsing policies that would prevent companies from doing the latter.

The irreplaceable Tim Carney explains in today’s Washington Examiner. Let’s start with what he wrote about oil companies.

…the “oil subsidies” Obama points to are broad-based tax deductions that oil companies also happen to get. I wrote last year about Democratic rhetoric on this issue: “tax provisions that treat oil companies like other companies become a ‘giveaway,’…”

I thought Romney’s response about corrupt Solyndra-type preferences was quite strong.

Here’s what Tim wrote about corporate jets.

…there’s no big giveaway to corporate jets. Instead, some jets are depreciated over five years and others are depreciated over seven years. I explained it last year. When it comes to actual corporate welfare for corporate jets, the Obama administration wants to ramp it up — his Export-Import Bank chief has explicitly stated he wants to subsidize more corporate-jet sales.

By the way, depreciation is a penalty against companies, not a preference, since it means they can’t fully deduct costs in the year they are incurred.

On another matter, kudos to Tim for mentioning corrupt Export-Import Bank subsidies. Too bad Romney, like Obama, isn’t on the right side of that issue.

And here’s what Tim wrote about “shipping jobs overseas.”

Obama rolled out the canard about tax breaks for “companies that ship jobs overseas.” Romney was right to fire back that this tax break doesn’t exist. Instead, all ordinary business expenses are deductible — that is, you are only taxed on profits, which are revenues minus expenses.

Tim’s actually too generous in his analysis of this issue, which deals with Obama’s proposal to end “deferral.” I explain in this post how the President’s policy would undermine the ability of American companies to earn market share when competing abroad — and how this would harm American exports and reduce American jobs.

To close on a broader point, I’ve written before about the principles of tax reform and explained that it’s important to have a low tax rate.

But I’ve also noted that it’s equally important to have a non-distortionary tax code so that taxpayers aren’t lured into making economically inefficient choices solely for tax reasons.

That’s why there shouldn’t be double taxation of income that is saved and invested, and it’s also why there shouldn’t be loopholes that favor some forms of economic activity.

Too bad the folks in government have such a hard time even measuring what’s a loophole and what isn’t.

Related Tags

Why Are Conservatives Incoherent on Federal Education?

For a nice overview of the counterproductive incoherence of Republican education efforts over the decades, check out this piece by Frederick Hess and Andrew Kelly of the American Enterprise Institute. And for a sense of how confused conservatives remain when they write pieces telling other conservatives how to have “good” federal education policy, read the same piece. Its history section gives you the first part, and, unfortunately, its other sections give you the rest.

Hess and Kelly — who are generally pretty sharp — furnish a terrific overview of what happens when you talk “local control” of government schools and decry federal micromanaging, but can’t stop yourself from spending federal money and love “standards and accountability.” Basically, you get a great big refuse heap of squandered money, red tape, educational stagnation, and political failure.

Having laid all that out pretty nicely, you’d think that Hess and Kelly would reach the logical conclusion: Conservatives should obey the Constitution and get Washington out of education. But they don’t. Instead they give precious little thought to the Constitution, and make policy prescriptions that fundamentally ignore that government tends to work for the people we’d have it control. You know, concentrated benefits, diffuse costs; iron triangles — basically, the big problems Hess and Kelly decry at state and local levels.

Start with their constitutional argument (such as it is):

The federal government does have a legitimate role to play in schooling — and it always has. From the Land Ordinance of 1785, which set aside land for the purpose of building and funding schools, through Dwight Eisenhower’s 1958 investment in math and science instruction after the launch of Sputnik, the federal government has recognized a compelling national interest in the quality of American education.

Wow! What a sweep of history! What a great many years this covers!

The thing is, most of those years see essentially no federal education activity, and the first year mentioned — 1785 — precedes the Constitution. Why very little activity between 1785 and 1958? Because relatively few people thought the national government had any role to play in governing education. That’s why neither the word “education” nor “school” (or, for that matter, “compelling national interest”) is in the Constitution, and even a commission created by Franklin Delano Roosevelt said that there is no constitutional federal role in education. Washington does have jurisdiction over District of Columbia schools, and a responsibility under the 14th Amendment to prohibit discrimination, but that’s it.

OK, to be fair, it could also be argued that Congress can constitutionally pass education provisions like those in the Land Ordinance. But not because Washington has power over education. No, because as you see in Article IV, Section 3 of the Constitution, it has power over territories. Of course, states and districts are not territories, and the 10th Amendment reiterates what is clear from the granting of only specific, enumerated powers to Congress:

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

In an effort to deal with the very clear failures of federal education policy — but without the clarity of following the Constitution — Hess and Kelly offer three things they think the Feds can and should focus on: transparency, research, and “trust-busting.” However, all three ignore the fundamental political reality that school systems tend to be controlled by their employees because the employees have the most at stake. And what are their incentives? Same as mine and yours: to get compensated as generously as possible and have no one hold them accountable for their performance. The result, of course, has been oodles of money spent without meaningful academic improvement.

Start with transparency. Lauding No Child Left Behind for having improved “citizens’ ability to gauge and compare school quality,” Hess and Kelly argue that the Feds “should require that states collecting federal school funds measure and report detailed data on school quality and educational costs in a consistent, uniform way.” They caution, however, that Washington shouldn’t prescribe standards or curricula, but should measure “schools’ return on public investment.”

Talk about conflicted! How exactly do Hess and Kelly expect the Feds to both stop short of mandating curriculum and standards, and provide an accepted measure of specific schools’ return on investment? Even if you could thread the needle for a while, it is very hard to imagine Washington not eventually narrowing acceptable measures down to a single curriculum and test so that results could be uniform and distilled into soundbites. And what would likely happen even if the standards started off rigorous and the testing tough? The employees who would ultimately be held accountable would simply move their dumbing-down pressure from state and local levels to the federal level, where policy was now being made. Nothing would be solved, and there would be huge added problems of a new, monolithic standard that could in no way effectively serve greatly diverse kids, as well as the quashing of competing curricular ideas.

Next we’ve got the research argument, which is predicated on the well-known contention that the incentives for private-sector investment in “basic” scientific research — which doesn’t offer immediate returns — are too weak to provide for optimal amounts. The Feds, therefore, have to step in with oodles of grant money. Hess and Kelly would like to extend that model to education research.

Education, however, is not particle physics, the kind of research we generally imagine as “basic.” The need for major equipment investment is not nearly as great for education, nor are the likely benefits of, say, studying the effects of flash cards as far distant as the industrial applications of string theory. Moreover, if we had broad school choice, with schools able to seek profit without penalty, educators would have every reason to invest in research and find better, more efficient ways to teach kids. Finally, there is good evidence that science funding is just as likely to translate into rent-seeking benefits to the scientists as scientific benefits to the public.

Oh, and the constitutional basis for education research spending? Hess and Kelly don’t even try to offer one.

Finally, we have “trust-busting.” Here even Hess and Kelly’s examples illustrate how mistaken their ideas are. While sensibly calling for a reduction in calcifying federal rules and regulations, Hess and Kelly also argue that the Feds should be able to set up “private” entities to compete with the public-school monopoly. They cite as an example the American Board for Certification of Teacher Excellence, which provides a teacher preparation and certification process separate from those established by states. They also note that ABCTE has been “generally neglected.” Which is probably a good thing. After all, think of two other “private” federal creations: Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Seems there can be big problems when Washington creates supposedly private entities.

Then there’s this: “A related role for federal lawmakers is to help lift the burden of bad past decisions and troubling policy legacies that hinder reform-minded state and local leaders.” Hess and Kelly argue that Washington should create a form of bankruptcy that lets states and districts render null and void labor contracts and other obligations that make it hard for them to do business. And what example do they use of organizations that have been crippled by “legacy” contracts? General Motors and Chrysler.

Of course, thanks to the federal government, GM and Chrysler didn’t go through normal bankruptcy, did they? No, they went through processes jury-rigged to favor politically important special interests. That lesson should be screaming at Hess and Kelly: Give Washington power over something and they won’t use it for the common good. They will use it to reward the politically powerful, the very state and local problem Hess and Kelly are trying to solve!

The simple reality is that the federal government is no less subject to special-interest control — the ultimate result of the basic political problem of concentrated benefits and diffuse costs — than state and local governments. Except, that is, that Washington is even more distant from the people than state and local governments, and if people don’t like their state or local schools they can at least move.

There is, really, only one solution to the basic government problem of concentrated benefits and diffuse costs, and we do no one any favors by denying it: We need to end government control of education. We need a free market, in which educators are free to teach as they see fit and are held accountable by having to earn the business of paying customers.

The federal role in getting to this, thankfully, is simpler than what must be done at state levels, where constitutional authority over education actually exists. All that Washington has to do is obey the Constitution and get out of education. And yes, Rick and Andrew, that is what the Constitution requires.