That’s the slogan the Transportation Security Administration is apparently using to entice people to apply for jobs as airport screeners. Now that they’re preparing to expand the use of whole body imaging scanners, which can produce moderately detailed nude images of travelers, maybe they should consider a tagline that doesn’t sound like it’s designed to recruit voyeurs.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

Constitutional Law

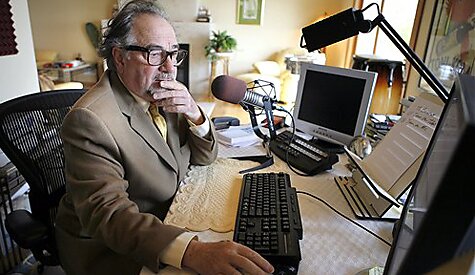

Michael Savage: Still Banned in the UK

In my Policy Analysis “Attack of the Utility Monsters,” I noted that U.S. talk radio host Michael Savage had been preemptively banned from entering the United Kingdom, for fear that he would incite hatred on arrival. I also noted that the ban had been rescinded — which, anyway, it appeared to have been at the time. Today I read that Savage’s travel ban is back on again.

What had Savage done that was so terrible? I’m not exactly sure, but here are some things that he’s said:

On homosexuality, he once said: “The gay and lesbian mafia wants our children. If it can win their souls and their minds, it knows their bodies will follow.”

Another of his pet topics is autism, which he claims is a result of “brats” without fathers.

He has also made comments about killing Muslims, although in one broadcast he cited extremists’ desires to execute gays as a reason for deporting them.

None are sentiments I agree with. In fact, I think all of them range somewhere from foolish to idiotic. Which is exactly why I’d welcome Michael Savage into a liberal, tolerant society: Let him contend with his betters, and he will lose. Treat him like a danger, and the tolerant society will appear weak — and intolerant.

Actually, Justice Breyer, the Constitution Enumerates Specific Powers, not Limitations on Otherwise Plenary Federal Power

Today I went to the Court to watch the argument in United States v. Comstock, which I blogged about previously and in which Cato filed an amicus brief. As I also blogged previously, Cato’s arguments so concerned the government that the solicitor general spent four pages of her reply brief going after them.

At issue is a 2006 federal law that provides for the civil commitment of any federal prisoner after the conclusion of his sentence upon the appropriate official’s certification that the soon-to-be-released prisoner is “sexually dangerous.” The problem is that, while states have what’s called a “police power” to handle this sort of thing — to appropriately deal with with threats to society from the dangerously insane and so forth — the federal government’s powers are limited to those enumerated in the Constitution. And I’m sorry, there’s no power to civilly commit people who have committed no further crime beyond those for which they’ve already been duly punished.

The government, having abandoned its Commerce Clause argument — a big loser in the lower courts — relied at the Supreme Court on the Necessary and Proper Clause. This clause says that Congress shall have the power to “make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution [the specific powers listed in Article I, section 8], and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the government of the United States.”

In other words, we have a government of delegated and enumerated, and therefore limited powers. As Ryan Lirette put it in National Review Online last week, “Congress may not search every corner of our country looking for problems to vanquish. Instead, Congress must be able to justify each law it passes with a specific congressional authorization.”

The solicitor general contends that civilly committing the sexually dangerous is “necessary and proper” to regulating the federal prison system — which itself is not an enumerated power but ancillary to enforcing federal criminal laws that Congress is appropriately empowered to make. At the argument, solicitor general Kagan further justified the relevant provision as related to “responsibly” releasing federal prisoners.

I don’t think her “cascading powers” theory of the Necessary and Proper Clause is a winner — for reasons I describe in my recent podcast — and Justice Scalia also wasn’t convinced. Justice Breyer, however, at one point asked where the Constitution prohibited the federal government from “help[ing] with” a problem it identified (see page 31 of the transcript) and in general was hesitant to find limits to congressional action to solve big policy areas.

Breyer has it all backward: We don’t operate on the premise that the government has full plenary power to do whatever it thinks is best, for the “general welfare,” for “the children,” for “society,” or for any particular group, checked only by specific prohibitions. Instead, our system of government — our constitutional rule of law — provides for islands of government involvement in a sea of liberty. It is individual people who can do whatever they want that isn’t prohibited by law, not the government.

And so we’ll see soon enough which vision of the relationship between citizen and state the Supreme Court embraces. Along with Justice Breyer, Justices Stevens and Ginsburg also were not very sympathetic to the federalism and libertarian arguments ably presented by federal public defender G. Alan Dubois. Along with Justice Scalia, Justice Alito was (refreshingly) skeptical of undue government power — and one would expect (the silent) Justice Thomas to be in that category as well. Justice Sotomayor also asked some interesting questions inquiring into the federal government’s ability to hold someone indefinitely — including on the relationship of that power to the Commerce Clause authority underlying most federal exercise of power — so she could go either way. Finally, the Chief Justice and Justice Kennedy were, uncharacteristically, not all too active — seeming to question both sides equally — so it’s hard to predict how the Court will ultimately rule.

Supreme Court Lets Eminent Domain Abuse Continue

Yesterday, the Supreme Court decided not take up an important takings case, the infelicitously titled 480.00 Acres of Land v. United States. As I blogged previously, Cato filed an amicus brief in the case in the hopes that the owner of the “480.00 Acres of Land,” Gil Fornatora, would ultimately receive the “just compensation” to which he is constitutionally entitled. The Court also missed the chance to correct the pattern of due process abuse that is apparently rampant in Florida. The case involved the federal government maneuvering to unjustly drive down property values before taking land for (legitimate) public use — in this case expanding the Everglades — thus greatly diminishing the compensation it was obligated to pay the owners. Fox News recently had a report about the case, in which I briefly appeared.

Interestingly — and sadly — since the Fox News report, my voicemail and email inbox has been receiving story after story of individuals who have experienced injustices similar to that of Mr. Fornatora. While it is unfortunate that this case has come to an end, the number of calls and emails leads me to believe that more cases like this will be making their way through the federal judiciary and that, eventually, this abuse will be halted.

To that end, while Cato does not involve itself directly in litigation, on the subject of takings and eminent domain abuse I can certainly recommend our friends at the Institute for Justice and Pacific Legal Foundation. Specifically on the type of “condemnation blight” at the heart of the Fornatora case, feel free to contact PLF’s Atlantic (Florida) office at (772)781‑7787 or write to Pacific Legal Foundation, 1002 SE Monterey Commons Blvd., Suite 102, Stuart, FL 34996. Steven Gieseler was the attorney who presented the Fornatora case to the Supreme Court, and who got me involved.

In other eminent domain news, George Will had an excellent column on January 3 condemning the pernicious Atlantic Yards land grab that you can read about here.

Eat, Pray, Love, Marry–as Long as You’re Heterosexual

Elizabeth Gilbert, the bestselling author of the memoir Eat, Pray, Love, is back with a new book, Committed: A Skeptic Makes Peace With Marriage. In her earlier book Gilbert reflected on her broken marriage, her travels around the world “looking for joy and God and love and the meaning of life,” and her determination never to marry again. In the new book we learn that she surprised herself by meeting a man worth settling down with, a Brazilian living in Indonesia. So they became a couple and settled near Philadelphia, with Jose Nunes regularly leaving the country to renew his visitor’s visa.

But then came a legal shock:

She was in the early stages of research for that book when Nunes was detained, after a visa-renewing jaunt out of the country, by Homeland Security Department officials at the Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport. Popping in and out of the country as he’d been doing was not legal, Nunes was told, and if he wanted to stay permanently they would have to marry.

Gilbert didn’t want to marry. She and Nunes spent 10 months traveling in Asia. But then, reading about marriage, writing about her aversion to marriage, getting closer to her new partner, she decided to marry. And so they did. And they lived happily ever after in the New Jersey suburbs.

A happy ending all around. As long as you’re heterosexual. Because, of course, if you’re gay, the U.S. government will tell you that your life partner from Brazil may be allowed to visit the United States, but he won’t be allowed to stay. And guess what? He could stay if you were married, but you can’t get married. Catch-22. And even though you could now marry in some foreign countries and some American states and the District of Columbia, the Defense of Marriage Act still prevents the federal government — including its immigration enforcers — from recognizing valid marriages between same-sex partners.

Is this just a theoretical complaint? As a matter of fact, not at all. At least two well-known writers have recently faced exactly the same situation Gilbert did: a Brazilian life partner who couldn’t live in the United States. Glenn Greenwald, a blogger, author of bestselling books, and author of a Cato Institute study on drug reform in Portugal, has written about his own situation and that of others. Like Greenwald, Chris Crain, former editor of the Washington Blade, has also moved to Brazil to be with his partner.

Carolyn See, reviewing Gilbert’s book in the Washington Post, wrote, “The U.S. government, like a stern father, proposed a shotgun marriage of sorts: If you want to be with him in this country, this Brazilian we don’t know all that much about, you’ll have to marry him.” A shotgun marriage, sort of. But at least the government gave Gilbert a choice. It just told Greenwald and Crain no.

This unfairness could be solved, of course, if the government would have the good sense to listen to Cato chairman Bob Levy, who wrote last week in the New York Daily News on “the moral and constitutional case for gay marriage.” And it may be solved by the lawsuit seeking to overturn California’s Proposition 8 that is being spearheaded by liberal lawyer David Boies and conservative lawyer Ted Olson, writes Newsweek’s cover story this week, “The Conservative Case for Gay Marriage.” Until then: eat, pray, love, marry — as long as you’re heterosexual.

George Clooney’s Docile Body

Running the airport maze to board my flight from Madrid back to the U.S. last week, I found myself thinking, with no small measure of envy, about Ryan Bingham, George Clooney’s character from Up in the Air. The ultimate frequent flier, Bingham slides shoes and belt off, flips laptop from case, and aligns them neatly on the x‑ray conveyor in a seamless, fluid display of security Tai Chi. He navigates from curb to gate and back with crisp efficiency, every motion practiced and automatic.

My envy was tempered somewhat as I reread Discipline and Punish on the trip back. Bingham’s military precision, it struck me, was the product of a form of training implicit in the security process. As a corrective brace “teaches” the proper posture just by making it the only comfortable one, the screening procedures embed a set of tacit instructions, consisting of the optimal set of motions required to pass through smoothly. And of course, it teaches more than bodily motions: Bigham knows you don’t stand behind the Arabs in the screening line!

That’s not to say airport security is some kind of insidious brainwashing program, but there’s a dimension of privacy here that it seems to me we don’t talk about nearly enough. Our paradigms of privacy harms are invasion (the jackboot at the door, in the extreme case) and exposure (the intimate detail revealed). We generally think of these as exceptions — as what happens when surveillance goes wrong, either because it gets the wrong target or, when the surveillance is universal by design, because information that’s supposed to remain protected falls into the wrong hands or is otherwise misused. Invasion and exposure may be serious problems, but they are fundamentally mistakes — hiccups in the system we can seek to fix.

Discipline, by contrast, is what inevitably happens when the system functions as intended, at least to the extent people are conscious of being (actual or potential) targets of surveillance. It is probably not as serious a harm as invasion or exposure most of the time, but it’s also by far the most pervasive and ineradicable effect of surveillance. It would be nice if our debates about surveillance included not just the question “What will be exposed?” but also “How — and for what — are we training ourselves?”

The Buck Stops with Obama

Today Politico Arena asks:

Do you feel safer from terrorism today than you did the day before? Assess Obama’s response.

My response: