I talked with Dennis McCuistion, whose interview program appears on KERA in Dallas and other public television stations, about “libertarianism and the politics of freedom.” It’s an old-fashioned public affairs program, where the host asks intelligent questions for half an hour. No shouting, no four-minute segments, a good solid conversation. Find the video here. Other McCuistion programs with such guests as Dan Mitchell, Steve Moore, and Steve Forbes can be found here.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

The Improving State of New York City, circa 1800–2007

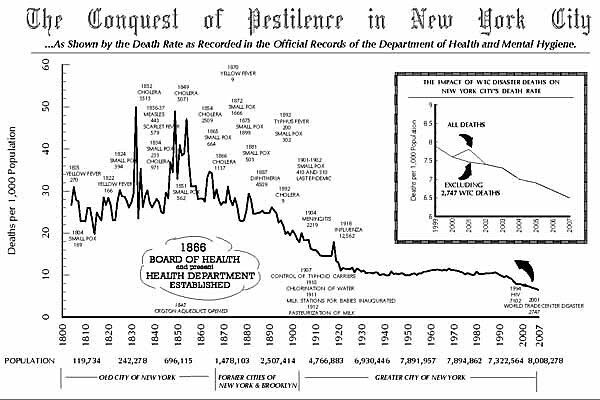

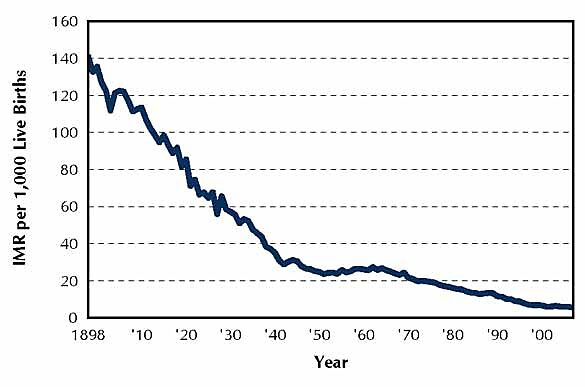

Two figures that say it all.

Death Rates (deaths per 1,000 population), New York City, c. 1800–2007. Source: NYC Department of Health & Mental Hygiene. Summary of Vital Statistics (2008). H/T to William Briggs for making me aware of this figure.

Infant Mortality Rate (deaths per 1,000 live births), New York City, 1898–2007. In 1898 IMR was estimated to be 140.9 Because of incomplete reporting of early neonatal deaths, this is almost certainly an underestimate. In 2007 IMR was 5.4 deaths per 1,000 live births. Source: NYC Department of Health & Mental Hygiene. Summary of Vital Statistics (2008)

Related Tags

A Tax That Would Finance the Road to Serfdom

Michael Tanner and Michael Cannon are working nonstop to derail government-run health care, but they better figure out how to work more than 24 hours per day, because if they fail, it is very likely that politicians will then look for a new revenue source to finance all the new spending that inevitably will follow. Unfortunately, that means a value-added tax (VAT) will be high on the list. Indeed, the VAT recently has been discussed by powerful political figures and key Obama allies such as the Co-Chairman of his transition team and the Speaker of the House.

The VAT would be great news for the political insiders and beltway elite. A brand new source of revenue would mean more money for them to spend and a new set of loopholes to swap for campaign cash and lobbying fees. But as I explain in this new video from the Center for Freedom and Prosperity, the evidence from Europe unambiguously suggests that a VAT will dramatically increase the burden of government. That’s good for Washington, but bad for America.

Even if the politicians are unsuccessful in their campaign to take over the health care system, there will be a VAT fight at some point in the next few years. This will be a Armageddon moment for proponents of limited government. Defeating a VAT is not a sufficient condition for controlling the size of government, but it surely is a necessary condition.

Related Tags

Tuesday Links

- How to measure the effectiveness of Obama’s stimulus plan.

- Forbes: The CBO estimate of the number of people who would stop being uninsured under the Senate Finance Committee proposal is exaggerated by at least 7 million to 10 million.

- Smoke and mirrors within the Senate Finance Committee?

- How to save democracy in Honduras.

- Video: Economist Daniel J. Mitchell discusses economic reform on CNBC.

Related Tags

Zero Tolerance for Difference

When both the New York Times and Fox News poke fun at a school district it’s a good guess that district has done something pretty silly. That seems to be the case in Newark, Delaware, where the Christina School District just suspended a 6‑year-old boy for 45 days because he brought a dreaded knife-fork-spoon combo tool to school. District officials, in their defense, say they had no choice — the state’s “zero tolerance” law demanded the punishment.

Now, the first thing I’ll say is that I was very fortunate there were no zero-tolerance laws — at least that I knew of — when I was a kid. Like most boys, I took a pocket knife to school from time to time, and like most boys I never hurt a soul with it. (I’m pretty sure, though, that I was stabbed by a pencil at least once.) I also played a lot of games involving tackling, delivered and received countless “dead arm” punches in the shoulder, and brought in Star Wars figures armed with…brace yourself!…laser guns! I can only imagine how many suspension days I’d have received had current disciplinary regimes been in place back then.

Before completely trashing little ol’ Delaware and all the other places without tolerance, however, there is a flip side to this story: Some kids really are immediate threats to their teachers and fellow students. And as the recent stomach-wrenching violence in Chicago has vividly illustrated, there are some schools where no one is safe. In other words, there are cases and situations where zero tolerance is warranted.

So how do you balance these things? How do you have zero-tolerance for those who need it, while letting discretion and reason reign for everyone else? And how do you do that when there is no clear line dividing what is too dangerous to tolerate and what is not?

The answer is educational freedom, as it is with all of the things that diverse people are forced to fight over because they all have to support a single system of government schools! Let parents who are not especially concerned about danger, or who value freedom even if it engenders a little more risk, choose schools with discipline policies that give them what they want. Likewise, let parents who want their kids in a zero-tolerance institution do the same.

Ultimately, let parents and schools make their own decisions, and no child will be subjected to disciplinary codes with which his parents disagree; strictness will be much better correlated with the needs of individual children; and perhaps most importantly, discipline policies will make a lot more sense for everyone involved.

Twombly and Iqbal: Reality Check

In Bell Atlantic v. Twombly (2007) and Ashcroft v. Iqbal (2009), the Supreme Court gave trial courts more latitude to dismiss a lawsuit at a very early stage, before the parties have had a chance to engage in discovery (the often lengthy and expensive fact-finding stage of civil litigation), if judges think the suit is not founded on “plausible” allegations of wrongdoing.

There’s a rich, angry debate about the effect the decisions will have on dismissal rates of meritorious suits in lower courts. But the consensus among academics seems to be that both decisions will trigger a sea-change in lower court practice—one deeply unfavorable to plaintiffs.

We won’t know the real effect of these decisions for many years to come. But a 2007 study by the Federal Judicial Center on the effect of a trio of similarly controversial 1986 Supreme Court decisions (known as the “Celotex trilogy”) raises questions about dire claims that Twombly or Iqbal will dramatically change lower court practice.

The debate over the Celotex trilogy in the 1980s is eerily similar to today’s debate over Twombly and Iqbal. Responding to concerns that juries award arbitrarily large judgments against corporate defendants, the Celotex trilogy gave lower courts more latitude to grant summary judgment—that is, to toss lawsuits at the end of discovery, before a case gets to a jury, when the judge thinks there is insufficient evidence to justify a jury trial. Many academics complained that the cases would result in a radical sea change in lower court practice—one that benefited corporate defendants at the expense of plaintiffs.

The FJC’s 2007 study is the most comprehensive study of the effect of the decisions to date. Based on data drawn from 15,000 docket sheets in randomly sampled terminated cases in six district courts, the FJC found (as expected) that, before and after the trilogy, summary judgment filing and disposition rates vary significantly from circuit to circuit and between types of cases. After controlling for differences in filing rates across circuits and for changes over time in the types of cases filed, the authors found that “the likelihood that a case contained one or more motions for summary judgment increased before the Supreme Court trilogy, from approximately 12% in 1975 to 17% in 1986, and has remained fairly steady, at approximately 19% since that time.” Moreover, between 1975 and 2000, “no statistically significant changes over time were found in the outcome of defendants’ or plaintiffs’ summary judgment motions, after controlling for differences across courts and types of cases.” Indeed, despite anecdotal claims that Celotex prompted a significant increase in summary judgment in civil rights cases, the authors found “no evidence that the likelihood of a summary judgment motion or termination by summary judgment has increased” in civil rights cases since 1986.

It’s easy to overstate the FJC’s findings. (The data tell us nothing about the quality of summary judgment decisions before or after Celotex, and shed no light on disposition rates at a micro-level, i.e. in product liability actions, as opposed to other tort actions, or Title VII actions, as opposed to other civil rights actions, for example.) The study nonetheless lends some plausibility to the view that Celotex was less a catalyst for change than a ratification of preexisting lower court practice that had evolved largely in spite of the Supreme Court and which the Court was, and is, largely powerless to control.

It’s easy to think of reasons why trial courts’ summary judgment practice might evolve independently of the Supreme Court. A surprisingly large number of trial court decisions, including grants of partial summary judgment, are not immediately appealable—and the pervasiveness of settlement means many of these decisions are never appealed. Intermediate appellate courts, moreover, affirm trial court decisions at an incredibly high rate. And the Supreme Court, which takes only about 80 appeals a year, has dramatically limited capacity to police the innumerable summary judgment dispositions made daily throughout the federal court system. The upshot is that trial courts, as a practical matter, have long had wide discretion to decide even pivotal motions, like summary judgment, with relatively light appellate oversight.

Are Twombly and Iqbal a replay of the Celotex trilogy? Only time will tell. But what we know, to date, about the Celotex trilogy suggests that, whatever you think about Twombly or Iqbal, strong claims about the influence of either decision may well overstate the Supreme Court’s power and influence over trial court practice.

Federal Reserve as Cash Cow

Scheduled for consideration before the House Financial Services Committee this week is a draft bill creating a Consumer Financial Protection Agency.

While there is a lot wrong with the bill — after all it is based on the premise that somehow consumers were tricked into not making a downpayment or re-financing thousands out of their homes, and then walking away — perhaps the most important provision, and the least discussed, is funding the agency by a transfer of cash from the Federal Reserve. Section 119 of the bill requires the Federal Reserve to transfer an amount equal to 10 percent of its expenses to the new agency’s Director.

This I believe is the first time in history that Congress is using the Federal Reserve to simply fund another agency. Why stop there, how about have the Fed just prints trillions of dollars to pay for the rest of the government? If Congress believes this agency will benefit the public, then the agency should be funded by the public, by a direct appropriations raised by taxes.

Of course after watching Ben Bernanke turn the Fed’s balance sheet into a slush fund for Wall Street, it was only going to be a matter of time before someone in Congress decided to use that slush fund for their own purposes. So much for transparency in government.