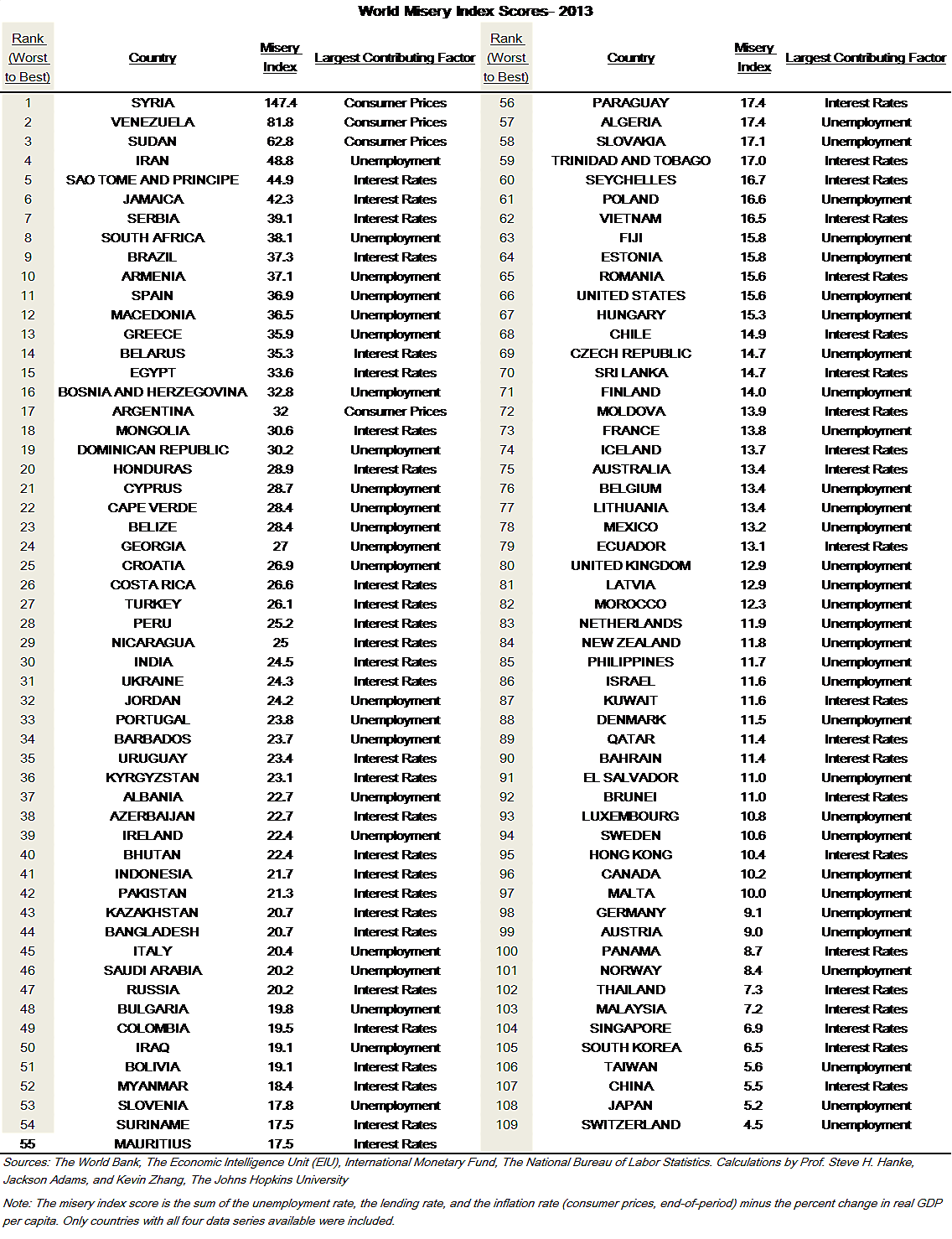

Every country aims to lower inflation, unemployment, and lending rates, while increasing gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. Through a simple sum of the former three rates, minus year-on-year per capita GDP growth, I constructed a misery index that comprehensively ranks 109 countries based on “misery.” Below are the index scores for 2013. Countries not included in the table did not report satisfactory data for 2013.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

The Costs of Ebola: Guinea and Sierra Leone

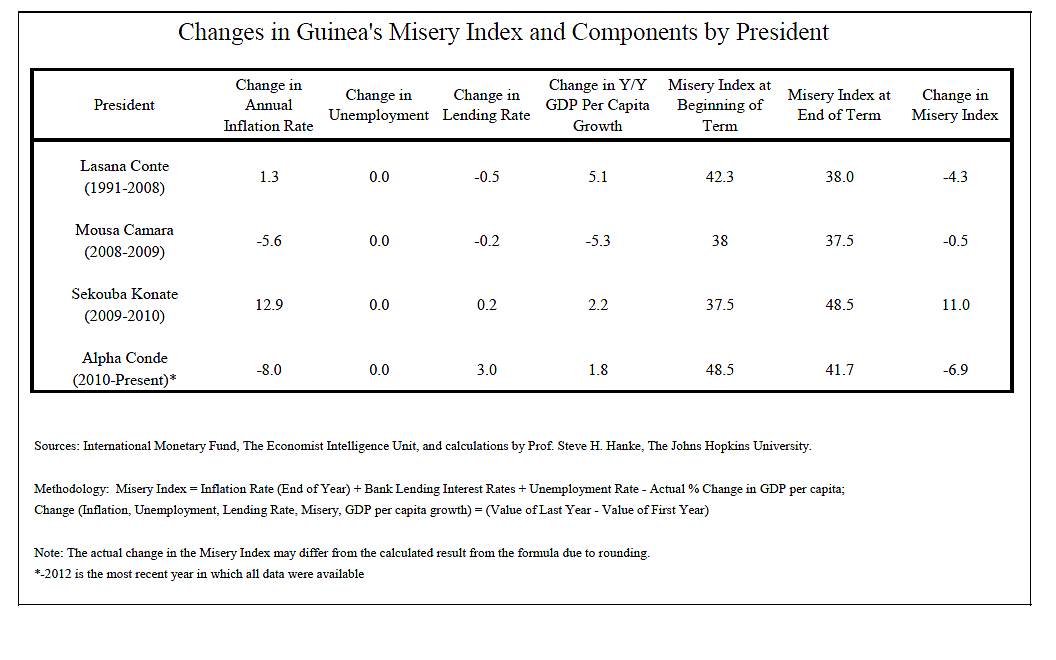

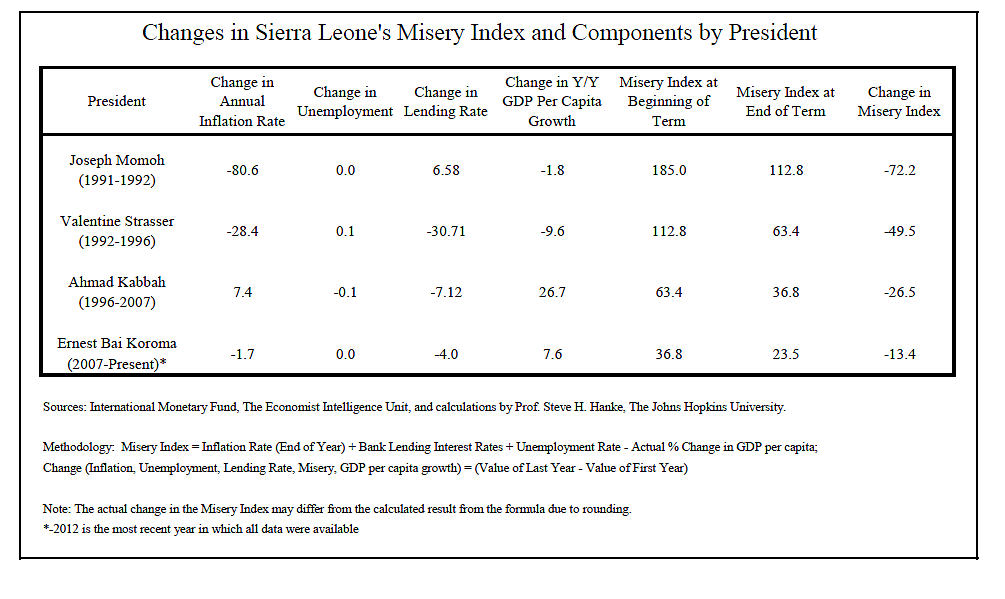

For a clear snapshot of a country’s economic performance, a look at my misery index is particularly edifying. The misery index is simply the sum of the inflation rate, unemployment rate and bank lending rate, minus per capita GDP growth.

The epicenter of the Ebola crisis is Liberia. My October 15, 2014 blog reported on the level of misery in and prospects for Liberia.

This blog contains the 2012 misery indexes for Guinea and Sierra Leone, two other countries in the grip of Ebola. Yes, 2012; that was the last year in which all the data required to calculate a misery indexes were available. This inability to collect and report basic economic data in a timely manner is bad news. It simply reflects the governments’ lack of capacity to produce. If governments can’t produce economic data, we can only imagine their capacity to produce public health services.

With Ebola wreaking havoc on Guinea and Sierra Leone, the level of misery is, unfortunately, very elevated and set to soar.

U.S.-Mexico Sugar Agreement: A Tribute to Managed Markets

The U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC) announced Oct. 27 that it had reached draft agreements with Mexican sugar exporters and the Mexican government to suspend antidumping and countervailing duty (AD/CVD) investigations on imports of sugar from that country. Commerce has requested comments from interested parties by Nov. 10, with Nov. 26 indicated as the earliest date on which the final agreements could be signed. Given the obvious level of consultation by governments and industries on both sides of the border leading up to this announcement, it’s reasonable to presume that the agreements will enter into effect within a few weeks.

Suspension agreements that set aside the AD/CVD process in favor of a managed-trade arrangement are relatively rare. They sometimes are negotiated when the U.S. market requires some quantity of imports, and when the implementation of high AD/CVD duties would be expected to curtail trade severely. This would have been the case, assuming the duties actually had entered into effect. However, as this recent blog post indicates, it’s not at all clear that the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) would have determined that imports from Mexico were injuring the U.S. industry. A negative vote (a vote finding no injury) by the ITC would have ended these cases and left the U.S. market open to imports of Mexican sugar.

What are the key provisions of the agreements? There are restrictions on both the price and quantity of imports from Mexico. Sugar will only be allowed to be imported into the United States if it is priced above certain levels: 20.75 cents per pound (at the plant in Mexico) for raw sugar, and 23.75 cents per pound for refined sugar. (For comparison, U.S. and world prices for raw sugar currently are about 26 cents and 16 cents, respectively; for refined sugar about 37 cents and 19 cents.) Additional price controls on individual Mexican exporters based on their alleged prior dumping (selling at a price the DOC determines to be less than fair value) will further raise the prices at which they will be allowed to sell.

Quantity restrictions on imports will be imposed through a formula related to supply and demand conditions in the U.S. market. A knowledgeable sugar industry analyst has calculated that Mexican exporters would be allowed to sell a minimum of approximately 1.3 million metric tons raw value (MMTRV) during the 2014–15 marketing year (Oct. 1, 2014 to Sept. 30, 2015). Depending on market conditions next spring and summer, that figure may rise to around 1.45 MMTRV. (Over the past seven years, imports from Mexico ranged between 0.629 MMTRV and 1.927 MMTRV.) No more than 60 percent of Mexico’s exports may be in the form of refined sugar. The timing of import arrivals will be controlled. Mexico will utilize export licenses to prevent more than 30 percent of its allowed sales from arriving in the United States during the October-December quarter, and no more than an additional 25 percent during January-March.

Since 2008 when NAFTA’s sugar provisions were fully implemented, there has been an open border for bilateral trade in sweeteners. Now that trade will be subject to a tightly controlled regime in which both governments will play important roles in making sure that market forces are not allowed to operate.

Who are the likely winners and losers from this new arrangement? As might be expected, the U.S. sugar industry got pretty much everything it wanted. Both price and quantity will be constrained in ways that keep the U.S. market isolated from the world. U.S. growers can be expected to continue to enjoy artificially inflated earnings.

Mexican growers got perhaps half of what they wanted. True, they have at least temporarily given up the open access to the U.S. sugar market that was negotiated under NAFTA. However, they have staved off what may have been the complete loss of their most important export market, in the event the ITC had ruled against them. They have obtained guaranteed access for slightly more than the quantity of sugar that had been exported to the United States on average in the seven years since NAFTA’s full implementation. And, as an additional benefit, the price restrictions imposed by the DOC will mean that they are likely to sell at higher prices in this managed market than would otherwise have been the case.

Officials in the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) who run the sugar program also likely see themselves as benefitting from the suspension agreements. They have the rather unenviable task of trying to manage sugar supplies from all sources. This not only includes imports from the 41 countries that have rights to export sugar to the United States under the tariff-rate quota (TRQ) system. It also encompasses commercial deliveries of sugar produced by U.S. growers, who accepted marketing limits years ago in order to retain their high level of government price support. Up until now, the only unregulated source of supply to the U.S. sugar market has been imports from Mexico. Managers of the U.S. market may find it easier to maintain a tight enough balance between supply and demand to prevent the price from falling to the support level. Low domestic prices lead to costs for USDA, which no doubt generates flak for the people running the program. (Note: Making it easier for officials to supplant the invisible hand of the marketplace likely wouldn’t be seen as a good thing by the late free trader, Adam Smith.)

It’s not hard to identify losers from a tightly managed U.S. marketplace. Anyone who uses sugar is paying more for it than it is worth in the outside world. A press release by the Sweetener Users Association indicates their concerns that additional import restrictions will lead to greater market uncertainty and higher prices. Consumers can expect to pay hundreds of millions of extra dollars per year for sugar-containing products. This cost increase will act like a regressive tax. Low-income people will forfeit a higher percentage of their incomes to pay for this new consumption “tax” than will people with relatively higher incomes. (Will the White House criticize the deal because it leads to greater inequality?)

Another likely group of losers are U.S. producers and exporters of high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS). The United States generally is believed to be the world’s lowest-cost producer of HFCS, which has become the preferred sweetener for soft drinks and other liquid applications in North America. U.S. exports of HFCS to Mexico have risen more than three-fold since 2007 and recently have amounted to a million metric tons per year. (Liberalization under NAFTA has led to active sweetener trade in both directions.) The suspension agreement generates uncertainty for HFCS producers because sugar that otherwise would have been exported from Mexico to the United States now may stay south of the border and be used instead of HFCS in soft drinks. It would not be surprising to see a notable decline in HFCS exports in the coming years.

On the other hand, Mexico had made clear its intention to retaliate in some form in the event AD/CVD duties were implemented against sugar, with HFCS being a likely target. (Note: Such retaliation likely would not be consistent with Mexico’s obligations under NAFTA and the WTO, but those commitments have not been much of a restraint in the past. The history of bilateral sweetener disputes provides ample evidence of Mexico’s ability to discriminate against imports of HFCS.) Thus, the U.S. HFCS industry may be hurt less by the suspension agreement than it would have been hurt by Mexico’s reaction to an adverse decision at the ITC. (Why is it that efficient industries often seem to suffer harm when governments try to protect inefficient industries?)

Of course, the U.S. and Mexican economies also will be losers under the settlement agreement. Both will tend to see scarce resources being allocated more poorly. GDP will be lower in each country, although minimally. Since the effects will be small, should we be concerned? The main concern is that this is one more among many policy choices in which the U.S. government has sided with special interests at the expense of the public interest. Could that be a reason that the economy has struggled to get back on its feet?

Which leads to the final loser: U.S. international trade policy. The United States currently is negotiating trade agreements including the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), and (at least still in theory) the World Trade Organization (WTO) Doha Round. Does making a public statement to the effect that protecting U.S. sugar growers is the central organizing principle of U.S. trade policy do anything to strengthen the hand of U.S. negotiators? Hardly. Rather, the suspension agreement with Mexico likely will make it more difficult to persuade Japan to eliminate tariffs on its sensitive agricultural products. Our Canadian neighbors are being challenged in the TTP to end their highly restrictive dairy and poultry programs. What kind of message does the sugar suspension agreement send to them? It might be best if U.S. trade policy was simply to take two aspirin and go to bed until 2017.

Are Well-Meaning but Misguided Conservatives Being Seduced by the Value-Added Tax?

Having a vision of a free society doesn’t mean libertarians are incapable of common-sense political calculations.

For example, the long-run goal is to dramatically shrink the size and scope of the federal government, both because that’s how the Founding Fathers wanted our system to operate and because our economy will grow much faster if labor and capital are allocated by economic forces rather than political calculations. But in the short run, I’m advocating for incremental progress in the form of modest spending restraint.

Why? Because that’s the best that we can hope for at the moment.

Another example of common-sense libertarianism is my approach to tax reform. One of the reasons I prefer the flat tax over the national sales tax is that I don’t trust that politicians will get rid of the income tax if they decide to adopt the Fair Tax. And if the politicians suddenly have two big sources of tax revenue, you better believe they’ll want to increase the burden of government spending.

Which is what happened (and is still happening) in Europe when value-added taxes were adopted.

And that’s a good segue to today’s topic, which deals with a common-sense analysis of the value-added tax.

Here’s the issue: I’m getting increasingly antsy because some very sound people are expressing support for the VAT.

I don’t object to their theoretical analysis. They say they don’t want the VAT in order to finance bigger government. Instead, they argue the VAT should be used only to replace the corporate income tax, which is a far more destructive way of generating revenue.

And if that was the final–and permanent–outcome of the legislative process, I would accept that deal in a heartbeat. But notice I added the requirement about a “permanent” outcome. That’s because I have two requirements for such a deal:

1. The corporate income tax could never be reinstated.

2. The VAT could never be increased.

And this shows why theoretical analysis can be dangerous without real-world considerations. Simply stated, there is no way to guarantee those two requirements without amending the Constitution, and that obviously isn’t part of the discussion.

So my fear is that some good people will help implement a VAT, based on the theory that it will replace a worse form of taxation. But in the near future, when the dust settles, the bad people will somehow control the outcome and the VAT will be used to finance bigger government.

Here are examples to show why I am concerned.

Here’s some of what Tom Donlan wrote for Barron’s.

…the U.S. imposes the highest corporate tax rate in the developed world. Make no mistake, corporations pay no tax. That is a tax on American consumers, American workers, and American shareholders. Don’t think that the corporate income tax eases your personal tax burden. Add your share of the corporate income tax to the other taxes you pay. Better yet, create a business tax we can all understand. A value-added tax is a tax on consumption. We would pay it according to the amount of the economic resources we choose to enjoy, and we would not pay it when we choose to save and invest in making the economy bigger and more productive. We would pay it on imported goods as much as on those domestically produced. The makers of goods for export would receive a rebate on their value-added tax. Trading the corporate income tax for the value-added tax is one of the best fiscal deals the U.S. could make.

I agree in theory.

America’s corporate tax system is a nightmare.

But I think giving Washington a new source of tax revenue is an even bigger nightmare.

Professor Greg Mankiw at Harvard, writing for the New York Times, also thinks a VAT is better than the corporate income tax.

…here’s a proposal: Let’s repeal the corporate income tax entirely, and scale back the personal income tax as well. We can replace them with a broad-based tax on consumption. The consumption tax could take the form of a value-added tax, which in other countries has proved to be a remarkably efficient way to raise government revenue.

Once again, I can’t argue with the theory.

But in reality, I simply don’t trust that politicians won’t reinstate the corporate tax. And I don’t trust that they’ll keep the VAT rate reasonable.

At this point, some of you may be thinking I’m needlessly worried. After all, journalists and academic economists aren’t the ones who enact laws.

I think that’s a mistaken attitude. You don’t have to be on Capitol Hill to have an impact on the debate.

Besides, there are elected officials who already are pushing for a value-added tax! Congressman Paul Ryan, the Chairman of the House Budget Committee, actually has a “Roadmap” plan that would replace the corporate income tax with a VAT, which is exactly what Donlan and Mankiw are proposing.

…this plan does away with the corporate income tax, which discourages investment and job creation, distorts business activity, and puts American businesses at a competitive disadvantage against foreign competitors. In its place, the proposal establishes a simple and efficient business consumption tax [BCT].

At the risk of being repetitive, Paul Ryan’s plan to replace the corporate income tax with a VAT is theoretically very good. Moreover, the Roadmap not only has good tax reform, but it also includes genuine entitlement reform.

But I’m nonetheless very uneasy about the overall plan because of very practical concerns about the actions of future politicians.

In the absence of (impossible to achieve) changes to the Constitution, how do you ensure that the corporate income tax doesn’t get re-imposed and that the VAT doesn’t become a revenue machine for big government?

By the way, this susceptibility to the VAT is not limited to Tom Dolan, Greg Mankiw, and Paul Ryan. I’ve previously expressed discomfort about the pro-VAT sympathies of Kevin Williamson, Josh Barro, and Andrew Stuttaford.

And I’ve written that Mitch Daniels, Herman Cain, and Mitt Romney were not overly attractive presidential candidates because they’ve expressed openness to the VAT.

This video sums up why a value-added tax is wrong for America.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b6JDpw8a2Hk[/embed]

Last but not least, let me preemptively address those who will say that corporate tax reform is so important that we have to roll the dice and take a chance with the VAT.

I fully agree that the corporate income tax is a self-inflicted wound to American prosperity, but allow me to point out that incremental reform is a far simpler–and far safer–way of dealing with the biggest warts plaguing the current system.

Lower the corporate tax rate.

Replace depreciation with expensing.

Replace worldwide taxation with territorial taxation.

So here’s the bottom line: If there’s enough support in Congress to get rid of the corporate income tax and impose a VAT, that means there’s also enough support to implement these incremental reforms.

There’s a risk, to be sure, that future politicians will undo these reforms. But the adverse consequences of that outcome are far lower than the catastrophic consequences of future politicians using a VAT to turn America into France.

P.S. You can enjoy some good VAT cartoons by clicking here, here, and here.

P.P.S. I also very much recommend what George Will wrote about the value-added tax.

P.P.P.S. I’m also quite amused that the IMF accidentally provided key evidence against the VAT.

Related Tags

Attorneys General Aim at New Targets, Who Respond as Expected

The New York Times launches a series of investigative reports on corporate lobbying of state attorneys general. But you have to read fairly far down in the story to find the “nut graf” on why this is happening now. Radley Balko summed it up in a tweet: “As prosecutors get increasingly powerful, lobbyists will increasingly spend money to try to influence them.” And the article does note that:

A robust industry of lobbyists and lawyers has blossomed as attorneys general have joined to conduct multistate investigations and pushed into areas as diverse as securities fraud and Internet crimes.…

The increased focus on state attorneys general by corporate interests has a simple explanation: to guard against legal exposure, potentially in the billions of dollars, for corporations that become targets of the state investigations.

It can be traced back two decades, when more than 40 state attorneys general joined to challenge the tobacco industry, an inquiry that resulted in a historic $206 billion settlement.

Microsoft became the target of a similar multistate attack, accused of engaging in an anticompetitive scheme by bundling its Internet Explorer with the Windows operating system. Then came the pharmaceutical industry, accused of improperly marketing drugs, and, more recently, the financial services industry, in a case that resulted in a $25 billion settlementin 2012 with the nation’s five largest mortgage servicing companies.

The trend accelerated as attorneys general — particularly Democrats — began hiring outside law firms to conduct investigations and sue corporations on a contingency basis.

I wrote about this 30 years ago in the Wall Street Journal, citing Hayek’s assessment from 40 years before that:

Nobel laureate F.A. Hayek explained the process 40 years ago in his prophetic book The Road to Serfdom: “As the coercive power of the state will alone decide who is to have what, the only power worth having will be a share in the exercise of this directing power.”

As the size and power of government increase, we can expect more of society’s resources to be directed toward influencing government.

Those who work to increase the size, scope, and power of government need to recognize: This is the business you have chosen. If you want the federal government to tax (and borrow) and transfer — and reallocate through prosecution — $3.8 trillion a year, if you want it to supply Americans with housing and health care and school lunches and retirement security and local bike paths, then you have to accept that such programs come with incentive problems, politicization, corruption, and waste. And that special interests will find ways to influence such momentous decisions, no matter what lobbying restrictions and campaign finance regulations are passed.

Armor’s Reply to Barnett: Research on Early Childhood Ed Still Unpersuasive

W. Steven Barnett’s attempt to rebut my review of preschool research begins with an ad hominem attack on my (and Cato’s) motives for publishing this piece, calling it an “October Surprise” with an aim “to raise a cloud of uncertainty regarding preschool’s benefits that is difficult to dispel in the time before the election.” He omits that my first review of preschool research was published in January, the same month Cato sponsored a public forum on the topic with both pro and con speakers. The current, expanded review was published now because it took me that long to finish it.

Of course, it is crucial to let the research and arguments speak for themselves, but for what it is worth, I have no formal affiliation with Cato or any other organization other than George Mason University, while Barnett is Director of The National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER), whose mission is to “support high-quality, effective early childhood education for all young children.” Barnett is a long-time advocate of universal preschool, while I had no position on pre‑k until I read reports from the national Head Start Impact Study (HSIS).

Moving on to substantive matters, Barnett says that because the successful Perry and Abecedarian programs were small and more intensive than current proposals, we should devote more resources to replicate them at scale, not discount them as of limited value in indicating how much larger, and different, programs would work. But current “high quality” pre‑K programs, including Abbott pre‑K, do not in fact replicate either of these programs. Moreover, Barnett ignores the national Early Head Start demonstration, a program similar to Abecedarian, which found no significant long-term effects in Grade 5 except for a few social behaviors of black parents–hardly an endorsement to make it universal. Moreover, this one area of positive effects is tempered by significant negative effects on certain cognitive skills for the most at-risk students.

The difference in outcomes between the tiny Abecedarian project and the national Early Head Start demonstration program may be simply one of scale and bureaucracy. There is an enormous difference between designing and implementing a program for a few dozen mothers and infants in a single community and doing the same for thousands of children in many different communities across the country. In a national implementation, there are many more opportunities for implementation problems in leadership, staffing, program design, and so forth.

About my criticism of Regression Discontinuity Design (RDD) studies, Barnett says the flaws I describe are “purely hypothetical and unsubstantiated.” But I’m not alone in perceiving them; my concerns are shared by Russ Whitehurst, former Director of the Institute for Education Research in the U.S. Department of Education. More importantly, Barnett says my criticism about attrition (or program dropouts) is pure speculation, which is simply untrue.

In my review, I reported that the Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Georgia treatment and control groups differed significantly in family background characteristics (Mother’s education and limited English proficiency) that are known to be related to achievement test scores. The Boston study reported a 20 percent dropout rate from the treatment group, and those students were more disadvantaged than the stay-ins. It is true, though, that I can’t estimate the dropout problem in Barnett’s 2007 Abbott study; he does not report or describe attrition rates, nor does he provide any benchmark data that would allow a reader to compare the treatment and control group prior to testing. For the RDD studies that provide data (many do not), there is no empirical support for Tom Bartik’s suggestion that the dropouts could be children from wealthier families. Where data has been reported, the dropouts are more disadvantaged on one or more socioeconomic characteristics.

Barnett next claims that the Head Start and Tennessee evaluations are “not experimental” but quasi-experimental, like the Chicago Longitudinal Study. Regarding Head Start, Barnett (relying on Tom Bartik), misunderstands a reanalysis of the Head Start data by Peter Bernardy, which I cited. The original Head Start study found no significant long-term effects. Bernardy simply did a sensitivity analysis by excluding control group children who had some type of preschool; he found no long-term effects, same as the original Head Start study.

Regarding the Tennessee experiment, Barnett is correct that I omitted a small positive effect for a single outcome: grade retention. But he conveniently fails to mention that the Tennessee experiment found no long-term effects for the major outcome variables, including cognitive performance and social behaviors, and there was even a statistically significant negative effect for one of the math outcomes.

He then complains that my cost figures are miscalculated, saying I should subtract costs for existing pre‑K programs and use “marginal” rather than average costs per child. On the first, point, my review simply says that “states could be spending nearly $50 billion per year to fund universal preschool”; there is no need to subtract existing costs because it is simply an estimate of possible peak expenditures. Regarding marginal vs. average costs, my $12,000 figure is based on 2010 per pupil costs. Current average costs are most certainly higher – the federal Digest of Education Statistics actually places total costs per-pupil at roughly $13,000 – and $12,000 is not unreasonable for marginal costs since 80% of education costs are for teacher salaries and benefits, the primary marginal cost components.

Barnett then argued that I “omit[ted] much of the relevant research,” implying I would get different results had I included other reviews, especially one by the Washington State Institute for Public Policy (WSIPP) published in January. This is simply inaccurate. The WSIPP report breaks programs down by state/city, Head Start, and “Model” programs. Of the 13 state preschool evaluations, my review included 8 (WSIPP counted three different reports for the Tulsa, Oklahoma, program as separate studies). Of the remaining five programs not in my review, three are RDD studies for Arkansas, New Mexico, and North Carolina with no information on attrition or relevant statistics to compare the treatment and control group at the time of testing. I did include the New Jersey Abbott program, despite this problem of interpretation, because it is frequently mentioned and promoted as a high-quality preschool program.

Of the three model programs in the WSIPP study, my review included two, Perry Preschool and the Abecedarian project. The third is the IDS program mentioned by Barnett and also reviewed by him in other reports. I have been unable to obtain a copy of this 1974 study, and Barnett’s review provides very little information about it. He reports a standardized effect size of .4 at the end of pre‑K, but with no documentation about treatment and control group equivalence at the start of preschool. Neither is there information about attrition or dropout rates during the preschool year. It is therefore hard to assess the reliability of this effect. He acknowledges that a later follow-up study to document long term effects in adulthood suffered from “severe attrition” and may not be reliable.

Most important, the average standardized effect that WSIPP found for all test scores across all state/city programs was .31, which is only somewhat higher than the average Head Start standardized effect of about .2 across all tests. One reason the WSIPP effect is higher than Head Start is the inclusion of the extraordinary standardized effects (.9 or so) for the three Tulsa studies. Furthermore, the WSIPP study also documented the fade-out effect.

I do not understand Barnett’s claim that the New Jersey Abbott program has effects “three times as large” as the Head Start study. His 2007 report says the gain in reading at age four “…represents an improvement of about 28 percent of the standard deviation for the control (No Preschool) group” and the gain in math “…represents an improvement of about 36 percent of the standard deviation for the control (No Preschool) group” These represent standardized effects of .28 and .36, which averages out to .33 and thus is about the same as the WSIPP average for all state/city programs. This is somewhat higher than the Head Start Impact Study (.2) but certainly not three times higher. Moreover, his study presents no information about attrition for the treatment group, nor does he provide the reader with a table that compares the treatment and control group on socioeconomic characteristics prior to or at the time of testing.

Perhaps the most important point in this debate is something that Barnett does not explain, which is how any of the studies we have discussed support universal preschool. The only studies that give reliable information – meaning valid research designs with statistically significant results – on long-term benefits such as crime, educational attainment, and employment are the Abecedarian and Perry Preschool programs. Even assuming that these programs could be generalized to larger populations (holding aside the contrary implications of Early Head Start), these programs apply only to disadvantaged children who need a boost. There is little justification based on these programs to claim that middle class children will experience the same benefits.

Related Tags

What Public Choice Theory Says about Ebola

What does public choice theory say about responding to Ebola?

That is: What are the costs and benefits of various policies – not to the public – but to self-interested politicians? Public choice theory holds that politicians’ interests don’t always coincide with the public’s, and sometimes they diverge quite sharply. When interests diverge, politicians will often side with their own self-interest, even at the expense of the public.

So what do they want? Politicians want public esteem. They want above all to be seen as heroes. If that means sacrificing civil liberties — to little or no public benefit — then they will do so.

This remains true even if the “heroic” measures at hand amount to Ebola security theater. It would appear that’s what we’re getting — a set of state-level quarantines that are actually contrary to what doctors and epidemiologists recommend. (No, the public probably won’t care what the experts say. I mean, look – the public still buys antibacterial soaps, and public health experts don’t recommend those either.)

In general, then, we can expect politicians to be eager to quarantine. This eagerness will be completely independent of the specific facts of any particular disease. Recall that lots of politicians once wanted to be able to set up an HIV quarantine, too, even long after it was well known that HIV can’t be transmitted by hugging, kissing, sharing utensils, sharing toilet seats, non-euphemistic cuddling, or what have you. (Wasn’t that a loooong time ago? No: It was just last year. And they got what they wanted.)

In short, whether or not a quarantine is right in any particular case – and it might be right in some cases, though I wouldn’t know – public choice theory says that politicians will err on the side of quarantine.

If that seems cynical, consider the flip side: Politicians also don’t want to look like the ones who let Ebola into the country. Note that one might look like the person who brought Ebola into the country even when one’s policies are responsible for exactly zero additional Ebola risk. Life is unfair sometimes. Even to politicians.

To look like a screwup, all you have to do… is nothing. The public will be left to stew in its fears, and they hate it when that happens. So they will punish you, and your party, at the next possible opportunity. (When is that again?)

The costs of doing nothing here are especially high if your constituency happens to be made up of conservatives – in whom Jonathan Chait has pointed out a strong emotional preference for purity and cleanliness. We should thus expect to find fear of contamination at or near the top of the to-do list for conservatives, who will try, first, to intensify these fears, and second, to promote their own policies as the only ones capable of relieving them.

Much as I may hate to say it, this model explains very well the actions of New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, who enacted an Ebola quarantine against consensus medical opinion. Nurse Kaci Hickox, herself quarantined, has since delivered a harrowing account of her chaotic re-entry experience. Hardly the hero’s welcome that she deserved.

Now, we might well expect Hickox to protest. After all, she was the one actually spending the days in isolation. We should consider then, the opinions of disinterested experts, who understand the risks but who did not have their personal liberty at stake. This letter in the New England Journal of Medicine seems especially on point:

[Quarantine for health workers] is not scientifically based, is unfair and unwise, and will impede essential efforts to stop these awful outbreaks of Ebola disease at their source, which is the only satisfactory goal. The governors’ action is like driving a carpet tack with a sledgehammer: it gets the job done but overall is more destructive than beneficial.

When Christie appeared to abandon his quarantine policy – and let’s be honest about it, that’s basically what he did – he explained himself as follows:

We’re trying to be careful here,” Christie said on NBC’s “Today,” referring to his state’s policy. “This is common sense, and … the American public believes it is common sense. And we’re not moving an inch. Our policy hasn’t changed, and our policy will not change.

It’s common sense! And yet common sense isn’t necessarily what’s called for here. Common sense may win elections, but viruses are a lot more like chemistry than they are like common sense. Common sense doesn’t vary, but viruses’ properties do vary, often tremendously. The appropriate measures for containing each of them will likewise, and these measures will not always include quarantine. In a case like this, politicians, who must run on common sense, and on common fears, are unfortunately the last people we should be listening to. We know their biases too well.