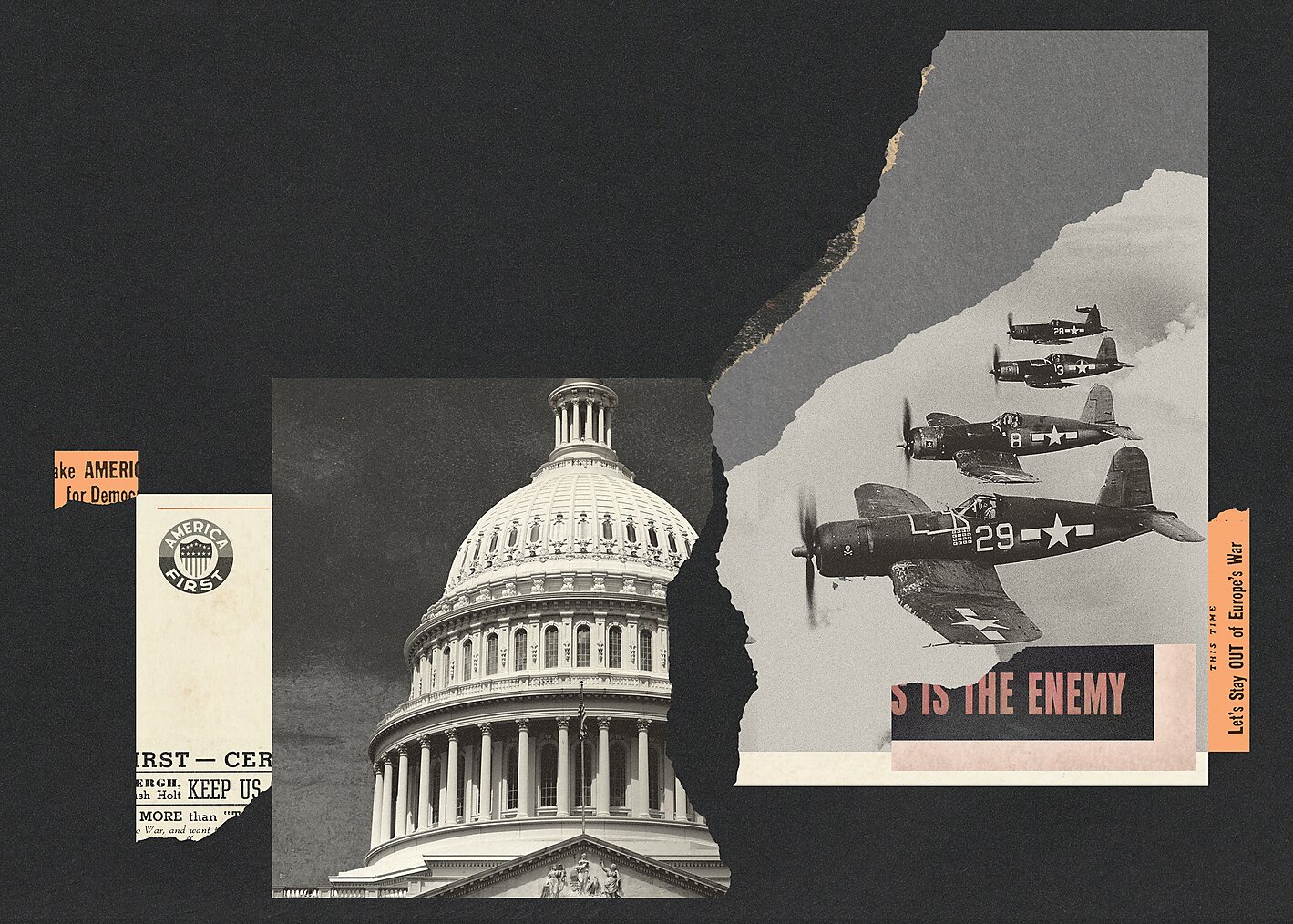

Illustration by Mark Weaver

The Lost Liberalism of America First

The original adherents of “America First” grounded themselves in a liberal tradition, arguing that entanglement in foreign wars would erode freedom at home and threaten our constitutional republic.

But the America Firsters of old would likely shudder at some of the distortions of the modern movement, which embraces executive power and bouts of hawkish militarism at the expense of liberty.

“

ur first duty is to keep America out of foreign wars. Our entry would only destroy democracy, not save it. ‘The path to war is a false path to freedom.’” Such was the first principle of the America First Committee (AFC), the long-defunct and often-maligned public pressure group that aimed to keep the United States out of World War II. Founded in 1940, the AFC grew into one of the largest noninterventionist groups in American history, drawing support from a broad cross-section of American society, including literary figures, newspaper publishers, business leaders, and politicians, among others. While the AFC’s adherents didn’t share an overall ideology, they all believed that America should avoid entanglement in foreign wars to preserve its republican institutions at home.

Admittedly, for some adherents, “America First” carried other darker meanings. Some have claimed its mantle championed antisemitism, nativism, and trade protectionism. These troubling aspects of the movement have dominated popular consciousness about America First since the end of World War II. In the Trump era, there are other flaws. For many self-described America First conservatives, the phrase has come to denote hawkish unilateralism, a celebration of militarism, and a continued desire to maintain global hegemony. These modern departures have reinforced negative perceptions of the phrase’s history and its implications for the present.

Yet beneath the modern political fervor and negative historical interpretations, the core of America First rooted its message in a liberal tradition—a desire to protect America’s unique experiment in individual liberty and limited government from the corruption of total war.

Yet beneath the modern political fervor and negative historical interpretations, the core of America First rooted its message in a liberal tradition—a desire to protect America’s unique experiment in individual liberty and limited government from the corruption of total war.

On the eve of the American entry into World War II, with the memories of the Great War fresh in their minds, those who opposed plunging into Europe’s latest conflagration saw themselves putting America first by staying out of the conflict and preventing the corrosion of individual liberty and republican norms. As evidence, they pointed to World War I’s egregious abuses of the Sedition Act, which resulted in the arrest and imprisonment of almost 1,000 Americans, formal censorship of interstate mail, and the empowerment of vigilante mobs aligned with the state. Many America Firsters on the eve of World War II also cited the country’s recent experience with the coercive practice of conscription as another institution that fundamentally transformed the individual’s relationship with the state. Speaking on his opposition to the draft, arch-noninterventionist Sen. Robert A. Taft (R‑OH)—a prominent conservative known as Mr. Republican—argued that the practice was “absolutely opposed to the principles of individual liberty, which have always been considered a part of American democracy.” While not an official member of the AFC, Taft nevertheless gave a consistent voice to the concerns of the organization and those within its orbit: namely, that to defeat fascism abroad, America would wind up emulating it at home.

They also feared the economic consequences. Drawing from the experience of World War I—and intensified by the New Deal—America Firsters saw war as a catalyst for the militarization of the economy and further entanglement between industry and the state. Before and during the war, opponents of American involvement in the conflict, such as John T. Flynn, head of the New York City AFC chapter, argued that government technocrats would use total war to implement what he sardonically called good fascism. In his 1944 treatise As We Go Marching, Flynn argued that war “will put in the hands of the all-powerful state … complete control of the economic system.” For critics like Flynn, the expansion of the federal bureaucracy, economic planning, and deficit spending foreshadowed a soft form of authoritarianism—a costly and invasive government run by unelected experts and solidified by total war. For America Firsters of old, the coming of war would do violence to individual rights and economic liberty, transforming the republic into an empire.

This political poster from 1940 captures the original spirit of the “America First” movement, which was rooted in noninterventionism and the preservation of our constitutional republic. (Photo by Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

A key mechanism of that transformation was the empowerment of the presidency. The issue of presidential authority reached its crescendo with the debate over the Lend–Lease Act. This law afforded the Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration sweeping authorities to aid the Allies and redefined America’s role in the war as that of a pseudo-belligerent. Sen. Burton K. Wheeler (D‑MT)—a progressive Democrat and supporter of the AFC—warned that the legislation afforded “one individual the dictatorial power to strip the American Army of our every tank, cannon, rifle, or antiaircraft gun” and send it abroad. An AFC analysis of the Lend–Lease Act also cautioned that it afforded to “the Executive alone … the power of legislating our foreign policy … without consultation with, or control by, Congress.” Viewing the Lend–Lease Act as another step toward war, and again with memories of World War I in mind, America Firsters worried correctly that the coming of war would empower the president at the expense of the people’s representatives, Congress.

While it would be tempting to ascribe such views to partisanship or the fleeting politics of the interwar era, alums of the America First movement and its successors maintained these concerns about executive authority throughout the early Cold War. A vocal opponent of this continuity of wartime exception was protolibertarian and old-right stalwart Rep. Howard Homan Buffett (R‑NE). Having assumed his seat in 1943, Buffett saw the Cold War as a continuation of a warfare state that abridged individual liberties, bloated spending, and increased inflation. Buffett warned that with Greece and Turkey within the fold, the impulse to intervene would not stop with the Truman Doctrine; rather, a “billion-dollar call will come from Korea” and next then “renewed demands from China,” and soon Uncle Sam would find himself “all over the world … answering alarms like an international fireman, maintaining garrisons, and pouring out our resources.” Like others in his cohort, Buffett warned that the coming showdown without the Soviets would infect domestic political discourse. Again, he prophetically saw that calls for fiscal prudence “would again be smeared as reactionary efforts to save dollars at the cost of the lives of American boys” and that “patriots who try to bring about economy would be branded as Stalin lovers.”

Putting America and Americans first ought to mean putting individual liberty, limited government, free markets, and peace at the core of a modern America First message, as they once were by its most consistent adherents.

Rep. Noah Mason (R‑IL) expressed his concern about Truman’s Republican successor as the Cold War expanded beyond Europe and East Asia. In his opposition to the Eisenhower Doctrine, which extended American foreign aid and military assistance in the Middle East, Mason explained in his dissent that the “Constitution places the power to make war in the Congress.” He added, “President Eisenhower has now asked Congress to grant him the authority to send our Army to the Middle East, at his discretion.” Through the 1950s, the spirit of America First jealously defended American republicanism even as the country grew into a globe-spanning empire.

When President Trump returned to the White House, he did so in part on a promise to restore an America First foreign policy. As a candidate, Trump rhetorically distinguished himself by running against a failed post–Cold War foreign policy consensus. However, as president, Trump has used the America First label to justify some stark departures from the past. While this new iteration of America First—like its namesake—strives to disengage militarily from Europe and eschews the idealism of multilateral security agreements and foreign aid, it seeks to maintain a hegemonic presence in the Middle East and East Asia. In the former region, despite eschewing the nation-building endeavors of his predecessors, President Trump nevertheless maintained the status quo relationship with Israel, participated in its 2025 war with Iran, and went as far as to unilaterally order—without even the pretense of congressional consultation—an airstrike on Iran’s nuclear facilities. Globally, this new iteration of America First possesses a fundamentally different view of the military-industrial complex and champions an amorphous vision of “peace through strength.” These are radical deviations from the America Firsters of old.

Where the original America First movement was animated by a defense of constitutional procedure and civil liberties, the language of liberty has largely given way to that of vigorous presidential action and national renewal. Many who claim the America First banner, including President Trump, no longer speak in the language of small‑r republicanism, congressional authority, or federalism. Instead, this new generation of “conservatives” seeks to mobilize the language of America First through the power of the presidency at the helm of a unitary federal government. Rather than seeking a return to a republic, many seek to continue the drive into empire.

These modern departures from America First’s liberal core have provided ample fodder for liberal and neoconservative critics and unsympathetic historians to tarnish the entire legacy of the phrase and its adherents. When joined with the fact that some of those who flocked to the banner to keep the United States out of World War II were motivated by racial prejudice and illiberal politics, these critics’ pronouncements have understandable rhetorical appeal. The excesses of the Trump era, coupled with the complexities of the past, have allowed these consensus voices to bury the lost liberalism of America First.

Putting America and Americans first ought to mean putting individual liberty, limited government, free markets, and peace at the core of a modern America First message, as they once were by its most consistent adherents. The current administration’s inability or unwillingness to live up to the best legacies of America First has left the lane open for libertarians to do so. Finally, emphasizing America First’s liberal roots could bridge political divides, appealing to civil libertarians on the left, mainstream liberals who still value peace, and traditionalist conservatives who treasure decentralization and localism.

In an age of permanent crisis, executive authority, and militarism, the original America First ideal remains relevant and urgently necessary. Rooting modern critiques of American foreign policy and its impacts at home in these historical narratives does not have to be saccharine or hide the warts of the past. We should not be ashamed about putting the America First movement’s best on display. Much about America First was worthy of emulation and indeed great. With equal degrees of passion and care, it can be again.