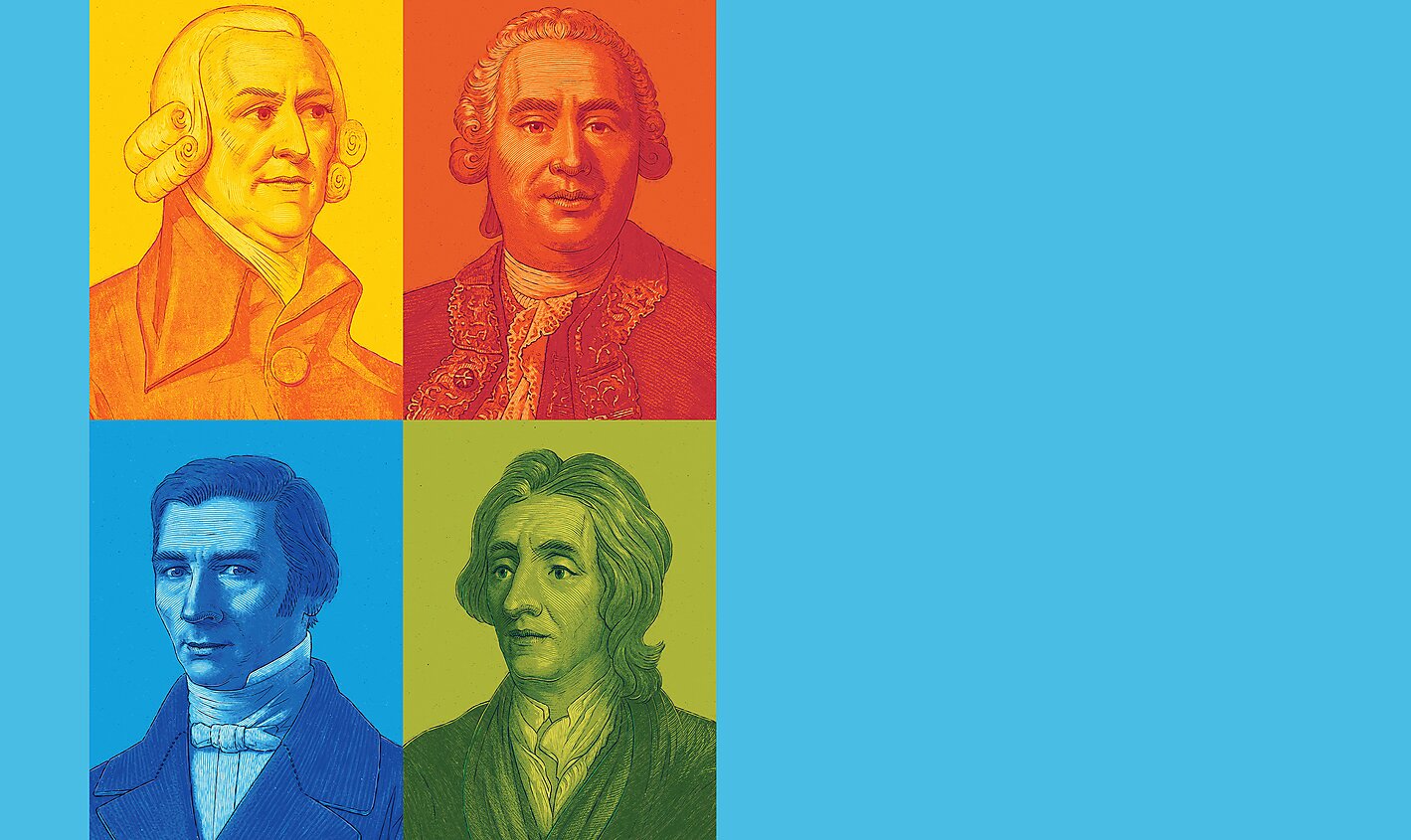

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: Adam Smith, David Hume, John Locke, and Frédéric Bastiat.

Illustration by Bartosz Kosowski

Free trade enriches us and enables human flourishing, but it is also a moral imperative essential to a just society.

Free trade enriches us and enables human flourishing, but it is also a moral imperative essential to a just society.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: Adam Smith, David Hume, John Locke, and Frédéric Bastiat.

Illustration by Bartosz Kosowski

resident Trump describes his tariffs as “a beautiful thing to behold” that will enable his administration to “Make America Great Again.”

Despite the bluster, economists from the left, right, and center have laid out the utilitarian case against protectionism in recent months: Tariffs are just taxes on imports that raise prices for consumers, distort market signals, provoke retaliatory trade barriers, and benefit the (often politically connected) few at the expense of the many. These economic realities will not bend to the president’s quixotic belief in the power of tariffs or his misunderstanding of trade deficits.

But beyond making a nation worse off in material terms, tariffs and protectionism also violate the principles of freedom and justice that are the hallmark of a free society, or what Adam Smith called a “great society.” Limiting the range of choices open to people via protectionist measures clashes with the fundamental, natural right to be free to choose, bounded by a just rule of law. When the law is used to coerce people and prevent mutually beneficial exchanges rather than safeguard persons and property, the moral fabric of society is eroded.

The utilitarian argument for free trade is essential, but the moral and strategic case for free trade must be vigorously emphasized and defended. The best way to make America great again is to safeguard free trade and show the world that voluntary market exchange under a liberal constitutional order is a surer path to human dignity and progress than protectionism.

The use of coercion to violate individual freedom is an act of injustice and hence immoral. An individual’s right to trade is a natural right that preexists government, not a privilege bestowed by the state. It is an essential condition for human flourishing.

Protectionism violates the principle of freedom and a just rule of law. As economist Leland Yeager has written: “Protectionism means using the force of government to keep people from trading as they see fit or to fine them for it. Free trade does not force; it permits.” By expanding the power of the state over the market, protectionism endangers the spontaneous order that emerges from private enterprise.

Voluntary exchange—based on private property, freedom of contract, and just laws—leads to mutual benefits, social and economic harmony, and peaceful development, as opposed to protectionism, which leads to crude nationalism and injustice. Trade is a win-win game for those freely entering into exchanges, which they expect to make them better off.

Of course, some people are harmed when consumers choose to move from one good or service provider (whether domestic or foreign) to another or when there are technological changes. But no one has an inherent right to succeed. Free markets are characterized by what Joseph Schumpeter famously called “creative destruction.” Old jobs are lost, and new jobs that have a higher value to consumers are created constantly in a dynamic market system. Those net benefits would be lost if the freedom to trade were suppressed.

In his Lectures on Jurisprudence (1762–63), Adam Smith argued that “it is commerce that introduces probity and punctuality.” Free trade engenders moral rectitude. Shopkeepers enhance their reputations by being honest and keeping their promises. If they wish to attract and retain long-run customers, they must be trusted and practice good manners.

Those who lie, steal, and cheat will not survive in a system based on private property rights protected by a legitimate rule of law safeguarding persons and property. As Smith noted, “When the greater part of people are merchants they always bring probity and punctuality into fashion, and these therefore are the principal virtues of a commercial nation.”

Sign up for our email newsletter now to get the latest digital Free Society issues delivered straight to your inbox.

John Locke, in his Second Treatise (1689), emphasized that “the end of law is not to abolish or restrain, but to preserve and enlarge freedom—for where there is no law, there is no freedom.” The reason is simple: “Liberty is to be free from restraint and violence from others, which cannot be where there is no law.” However, “freedom is not … a liberty for every man to do what he [wishes].” Rather, it is “a liberty to dispose and order … his person, actions, possessions, and his whole property, within the allowance of those laws under which he is [subject]; and therein not to be subject to the arbitrary will of another, but freely follow his own.” These passages crystallize the close relation between law, liberty, and justice and support the moral case for free trade.

Following in Locke’s footsteps, Smith argued in Lectures on Jurisprudence: “The first and chief design of all civil governments is to preserve justice amongst the members of the state and prevent all encroachments on the individuals in it, from others of the same society.” In other words, the role of the state is “to maintain each individual in his perfect rights,” which include “a right of trafficking [trading] with those who are willing to deal with him.”In particular, “the right to free commerce … when infringed” is an encroachment “on the right one has to the full use of his person … to do what he has a mind when it does not prove detrimental to any other person” (emphasis added).

Property, freedom, and justice are inseparable in the liberal constitutional order: When private property rights are violated, individual freedom and justice suffer. Governments that choose the path of protectionism diminish their moral authority.

The concept of “perfect rights” lies at the heart of a just market order. As Smith pointed out, “Perfect rights are those we have a title to demand and if refused to compel another to perform.” In contrast, “Imperfect rights are those which correspond to those duties which ought to be performed to us by others but which we have no title to compel them to perform.” Perfect rights can be enjoyed by everyone and, when safeguarded by the law of justice, lead to social and economic harmony.

For Smith, the natural right to be left alone to exercise one’s reason and freely trade with others, provided his perfect rights were guarded by the law of justice, was self-evident. As he declared, “That a person has a right to have his body free from injury, and his liberty free from infringement unless there be a proper cause, nobody doubts.” He would be shocked to hear President Trump say that “the word ‘tariff’ is the most beautiful word in the dictionary.”

James Madison, the chief architect of the Constitution, echoed Locke and Smith in 1792 when he wrote that the primary function of government is “to protect property of every sort; as well that which lies in the various rights of individuals, as that which the term particularly expresses. This being the end of government, that alone is a just government, which impartially secures to every man, whatever is his own” (emphasis added).

Just as freedom depends on the moral right to property, justice depends on limiting the use of force—whether individual or collective—to the safeguarding of life, liberty, and property. Justice does not refer to outcomes but to rules: To be just, rules must be applied equally and not violate our basic right to noninterference, which Cato senior fellow Roger Pilon has called “the most basic right … for it is logically prior to all other rights.”

Protectionism stirs up hatred and conflict; trade wars can lead to real wars that harm millions of people. Although free trade is not sufficient to avoid war, it is a necessary condition for peaceful coordination, both domestically and internationally.

Justice is simple to understand in the liberal constitutional order: It is merely the absence of injustice, which is defined as the wrongful taking of life, liberty, or property. As Frédéric Bastiat wrote in 1850:

When law and force confine a man within the bounds of justice, they do not impose anything on him but a mere negation. They impose on him only the obligation to refrain from injuring others. They do not infringe on his personality or his liberty or his property. They merely safeguard the personality, the liberty, and the property of others. They stand on the defensive; they defend the equal right of all. They fulfill a mission whose harmlessness is evident, whose utility is palpable, and whose legitimacy is uncontested.

In sum, property, freedom, and justice are inseparable in the liberal constitutional order: When private property rights are violated, individual freedom and justice suffer. Governments that choose the path of protectionism diminish their moral authority.

Free trade fosters economic development and provides individuals with the means to liberate themselves from the state. A growing middle class will have a strong economic stake in determining their own political fate. As Lee Teng-hui, former president of Taiwan, put it in 1996: “Vigorous economic development leads to independent thinking. People hope to be able to fully satisfy their free will and see their rights fully protected. And then demand ensues for political reform.”

Protectionism stirs up hatred and conflict; trade wars can lead to real wars that harm millions of people. Although free trade is not sufficient to avoid war, it is a necessary condition for peaceful coordination, both domestically and internationally. Trade develops a culture of freedom and strengthens civil society.

China went from autarky to the largest trading nation in the world when it opened the door for foreign trade. The economic reforms begun by Deng Xiaoping in late 1978—though incomplete, to be sure—paved the way for the spontaneous development of the private sector, which became the driving force for lifting millions of people out of poverty. The mantra in China became “peaceful development” as opposed to “ideological struggle.” The current trade war is leading to crude nationalism and threatening the freedom not only of Americans but also of people around the world.

A misplaced concern with trade deficits and a zero-sum mentality are the twin evils of protectionism. They tear people and nations apart. In his essay “Of the Jealousy of Trade” (1758), David Hume was correct to point out that “where an open communication is preserved among nations, it is impossible but the domestic industry of everyone must receive an increase from the improvements of the others.” That truth should not be forgotten.

Hong Kong’s unilateral move toward free trade made it rich; it did not impoverish the rest of the world. It was a beacon of light until China took control in 1997. The lesson is that although free trade is desirable on its own merits and on moral grounds, it cannot by itself bring about peace in the world. However, without free trade, the chances for peace substantially decrease.

Free trade has greatly benefited mankind. Its preservation is essential to maintain a free society and prosperity. As Bastiat wrote, “It is under the law of justice, under the rule of right, under the influence of liberty” that individuals will realize their “full worth and dignity.” In a system of law, liberty, and justice, diverse interests will “tend to adjust themselves naturally in the most harmonious way.”

We know from the principle of comparative advantage that specialization and free trade lead to net benefits for society. Nations can consume more than they produce domestically, gain from the free flow of ideas, safeguard against local supply-side shocks, and benefit from a wider range of choices.

In addition to all those benefits, free trade is a moral imperative. It is based on the natural rights to liberty and property, which in turn rest on a just rule of law designed to prevent injustice—that is, the taking of property, broadly conceived, without the consent of the injured party. By placing government above the law of liberty, protectionism undermines the moral fabric of a great society.

More in this Issue