The deadlocked Supreme Court couldn’t issue an opinion, but still left in place the block on President Obama’s immigration actions. The lower courts had correctly found that the executive actions implementing DAPA violated both administrative law and immigration statutes so, for practical purposes, it wouldn’t have mattered if Justice Scalia had still been on the bench to make this a 5–4 decision against the government. In any case, DAPA is now dead and so is any chance for immigration reform until the next president. That’s why those of us favoring reform in this area counseled against the president’s attempt to rewrite the law via executive action. This country’s immigration system is a mess — not serving anyone’s interests, let alone national security — but changing the law requires a new law.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

Affirmative Action Ruling Disappointing but Narrow

The Supreme Court’s 4–3 ruling upholding UT-Austin’s use of racial preferences in admissions was surprising and disappointing. Justice Alito does well to call out the majority’s imperial opinion as having no clothes. “Something strange has happened since our prior decision in this case,” he begins in his magisterial dissent — referring to the Court’s 2013 ruling directing the lower court to scrutinize university officials’ self-serving justifications for their policy.

“Even though UT has never provided any coherent explanation for its asserted need to discriminate on the basis of race,” Alito concludes in a way I can’t improve upon, “and even though UT’s position relies on a series of unsupported and noxious racial assumptions, the majority concludes that UT has met its heavy burden.” (He cites Cato’s two amicus briefs for the proposition that UT’s misleading legal arguments can’t be trusted.)

The best that can be said about this decision is that it’s limited to the weird affirmative action program that UT-Austin uses, which is unique in the country. Future lawsuits are still possible, and will depend on the type of racial preferences challenged and, of course, the composition of the Supreme Court.

Yes, the Federal Reserve Has a Diversity Problem

Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen recently appeared before the Senate Banking Committee to deliver the Semiannual Monetary Policy Report to the Congress. A handful of Senators queried Yellen as to the lack of diversity among both the Fed staff and the members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC).

Here, for example, is the exchange between Senator Warren and Yellen (paraphrased, as I heard it):

Warren: Diversity is very important. Studies show gender diversity in leadership makes for stronger institutions. I’m not surprised there’s a stunning lack of diversity at our biggest financial institutions. The Fed’s leadership diversity is somewhat better, but not a whole lot better. … Does lack of diversity among regional Fed presidents concern you?

Yellen: Yes, I believe it’s important to have diverse groups of policy makers who can bring different perspectives to bear. It is the responsibility of regional banks’ Class B and C directors to to conduct a search and identify candidates for regional Fed presidents. The Board reviews those candidates and we insist the search be national and every attempt is made to identify a diverse pool of candidates.

Warren: But what about the outcome? When a new regional Fed president is selected by the regional Fed board that person must be approved by you and others on the Board of Governors before taking office. The Fed Board recently reappointed each and everyone of these presidents without any public debate or any public discussion about it. If you’re concerned about diversity, why didn’t you use these opportunities to say enough is enough? Let’s go back and see if we can find qualified regional presidents who also contribute to the overall diversity of the Fed’s leadership?

Yellen: Well we did undertake a thorough review of the reappointments … [etc., etc.]

Warren: [Interrupting] But you’re telling me diversity’s important and yet you just signed off on all these folks without any public discussion about it. …The selection process is broken. Congress should take a hard look at reforming the regional Fed selection process so that we can all benefit from a Fed leadership that reflects a broader array of backgrounds and interests.

While it is tempting to dismiss such questions as mere identity politics (I’m waiting for Trump to complain about bringing in the Fed Vice Chair from Israel), the Fed has increasingly over time come to look less and less like the rest of America.

Should this matter, at least in terms of monetary policy? I believe it should.

We are a big country and, despite a focus on national aggregates, different parts of the country experience different economic conditions. California isn’t Texas; nor is it Ohio or New York. To some extent these regional differences are why we have the convoluted regional structure of the FOMC. Different voices can bring their experiences and local knowledge to bear in a manner that should result in a monetary policy that weighs the conditions of both New York and Ohio (as well as the rest of the country). Researchers have found that local economic conditions do indeed influence voting behavior on the FOMC. The finding holds not just for the regional bank Presidents, but also for Fed governors.

Of course geography is only one element. Having Fed leadership from different segments of our society, as well as different disciplines, encourages multiple approaches to problem-solving. While I am an economist and see a lot of value in economics, I’d be the first to say economics doesn’t have all the answers. Similarly, bankers can have important insights into the functioning of the economy, but so can manufacturers, retailers and farmers.

A greater variety of backgrounds could also improve Fed communications. Spending a lot of time around economists, I think it is fair to say we often speak a different language, sometimes foreign and strange to outsiders. A Fed board where deliberations occur across disciplines could improve the explanations of those deliberations to the broader public. I know I’ve often learned a considerable amount of economics in the process of trying to explain something to non-economists.

It is perhaps for this reason that Section 10 of the Federal Reserve Act requires that

In selecting the members of the Board, not more than one of whom shall be selected from any one Federal Reserve district, the President shall have due regard to a fair representation of the financial, agricultural, industrial, and commercial interests, and geographical divisions of the country.

Despite the clear language of Section 10, since 1996 80 percent of Fed governors have come from the East Coast (which has only about 30 percent of the population). The chart below shows successful nominees and the Federal Reserve district they were connected with, as viewed by the President who nominated them, the Senate who approved them, and the district of the nominees birth. The fact is we are not getting a monetary policy reflecting the perspectives and needs of the entire nation, but rather one concentrating on those of New York and Washington (which falls in the Richmond district).

To some extent the heavy concentration of appointments to the Board from NY, Boston and DC reflects the revolving door between the Fed, the financial industry and the executive branch (particularly the Treasury and the Council of Economic Advisors). So the lack of diverse perspectives is likely even worse than it seems. Not only do Fed appointments reflect biases favoring New York, but predominately biases favoring New York’s financial industry. Similarly, for Washington, appointments reflect biases favoring the Treasury department or the status quo thinking in monetary economics.

As both The Wall Street Journal and the Harvard Business Review have noted, the FOMC has come to be dominated by academic economists. Josh Zumbrun observed in 2015:

Of the 17 Fed officials in office next year—five members of the Board of Governors and 12 regional bank presidents—all but three will have professional backgrounds as academics or with Goldman Sachs. The exceptions will be Atlanta Fed President Dennis Lockhart and Fed governor Jerome Powell, who worked at other banking institutions, and Kansas City Fed President Esther George, who was primarily a bank supervisor.

About 70 percent of Fed Board members and regional Presidents were once either Fed economists or academics:

Educational background of FOMC’s members has also become more concentrated around PhDs in economics:

Additionally, Fed economists themselves are heavily concentrated among the graduates of a handful of graduate programs:

Don’t get me wrong. A couple of smart economists with degrees from MIT, who have lived most of their lives in either Boston, New York or DC, are certainly able to contribute to monetary policy. But when the entire system starts to consist of individuals from the same small number of cities, who graduated from the same schools and studied the same disciplines, then “yes” we have a problem. You are guaranteed to have an institution that suffers deeply from groupthink, as well as being insulated from the everyday experiences of most Americans.

Senator Warren suggests that “the selection process is broken.” I couldn’t agree more. To repair it, we must first recognize that the choice of Fed Board members begins with the President. At a minimum the President should faithfully follow the considerations spelled out in Section 10 of the Federal Reserve Act. If he fails to do so, as was the case with the nomination of Peter Diamond, the Senate is obligated to reject that nomination. While Diamond’s case was clear, previous nominations have been less so. To provide some clarity, I would suggest that Congress amend Section 10 to list specific conditions determining residency. I believe a minimum of ten years actual residency should be the requirement for a nominee to be “from” a particular Fed district.

Congress could put additional limitations on Board appointments to increase diversity. For example, amending Section 10 to state that no more than two board members may come from any one of “finance, manufacturing, agriculture, government or academia” would reduce groupthink and likely increase the quality of decision-making at the Fed. Slowing the revolving door between the Fed, Treasury and finance could also increase diversity. I would suggest we ban from consideration for Fed nomination anyone who has served in the executive branch in the previous six years and impose a similar ban for those working for institutions regulated by the Fed.

Having worked on Fed nominations as a staffer for the Senate Banking Committee, I’d be the first to say that the Senate has too often rubber-stamped a President’s Fed nominees. Recent years have witnessed an improvement in Senate due diligence, but far more needs to be done. Changes in the norms behind Senate consideration may not be durable. Accordingly changes to the selection process for the FOMC are badly needed. I agree with Sen. Warren, the Fed needs leadership with a “broader array of backgrounds and interests.” Which means the definition of diversity must also include geographic diversity, educational diversity, and diversity of professional experience. The quality of monetary policy-making depends on it.

Related Tags

A Century of Precipitation Trends in Victoria, Australia

In the debate over CO2-induced global warming, projected impacts on various weather and climate-related phenomena can only be adjudicated with observed data. Even before the specter of dreaded global warming arose, scientists studied historical databases looking for secular changes or stability. With the advent of general circulation climate models, using historical data, scientists can determine whether any observed changes are consistent with the predictions of these models as atmospheric carbon dioxide increases. An example of the pitfalls in such work was recently presented by Rahmat et al. (2015), who set out to analyze precipitation trends over the past century at five locations in Victoria, Australia. More specifically, the authors subjected each data set to a series of statistical tests to “analyze the temporal changes in historic rainfall variability at a given location and to gain insight into the importance of the length of data record” on the outcome of those tests. And what did their analyses reveal?

When examining the rainfall data over the period 1949–2011 it was found that all series had a decreasing trend (toward less rainfall), though the trends were significant for only two of the five stations. Such negative trends, however, were reversed to positive in three of the five stations when the trend analyses were expanded over a longer time domain that encompassed the whole of the 20th century (1900–2011 for four stations and 1909–2011 for the fifth one). In addition, the two stations with statistically significant negative trends during the shorter time period were also affected by the longer analysis. Though their trends remained negative, they were no longer statistically significant when calculated over the expanded 112 years of analysis. In summation, in the expanded analysis the “annual rainfall time series showed no significant trends for any of the five stations.”

In light of the above findings, Rahmat et al. write that “conclusions drawn from this paper point to the importance of selecting the time series data length in identifying trends and abrupt changes,” adding that due to climate variability, “trend testing results might be biased and strongly dependent on the data period selected.” Indeed they can be; and this analysis shows the absolute importance of evaluating climate model projections using data sets that have been in existence for sufficiently long periods of time (century-long or more) that are capable of capturing the variability of climate that occurs naturally. And when such data sets are used, as in the case of the study examined here, it appears that the modern rise in CO2 has had no measurable impact on rainfall trends in Victoria, Australia.

Reference

Rahmat, S.N., Jayasuriya, N. and Bhuiyan, M.A. 2015. Precipitation trends in Victoria, Australia. Journal of Water and Climate Change 6: 278–287.

Related Tags

The Case for Restraint: History and Politics

The third in a series of panels at last week’s conference on restraint explored the evolution of foreign policy in America—from the Founders’ embrace of restraint to Theodore Roosevelt’s interventionism to our current strategy of primacy. Speaking first, William Ruger of the Charles Koch Institute affirmed the roots of restraint in American history by presenting the Founders’ pillars of strategic independence and neutrality. Ruger explained how those principles guided U.S. foreign policy from the nation’s founding through the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898.

Edward Rhodes of George Mason University followed with an analysis of Theodore Roosevelt’s ideas about politics, society, and foreign policy. According to Rhodes, Roosevelt feared that if left unchecked, the liberalism of the previous era would lead the moral decay of America. Roosevelt believed waging war, crusading, and searching abroad for challenges would strengthen American virtues and thus provide the needed balance to American liberalism.

Lastly, Cato’s Trevor Thrall discussed the current state of politics as it relates to foreign policy. Thrall presented polling data to demonstrate that while the foreign policy establishment continues to defend vociferously the merits and wisdom of primacy, a large contingent of Americans would prefer a restrained, less interventionist foreign policy. This “restraint constituency,” in fact, outnumbers supporters of primacy by nearly a two-to-one margin.

You can watch the full panel here.

Related Tags

Update on Unaccompanied Alien Children

A new Congressional Research Service report provides a handy overview of the current state of knowledge surrounding Unaccompanied Alien Children (UAC) apprehended on the Southwest border. Many Central American children and other family members have crossed the border and sought asylum in the United States.

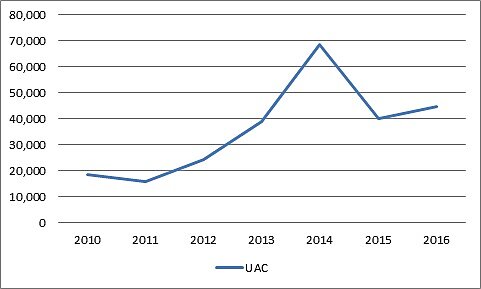

UAC apprehensions so far in 2016 exceed those apprehended in 2015 but they are still below the peak year of 2014 (See Figure 1).

Figure 1

Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions

Source: Customs and Border Protection.

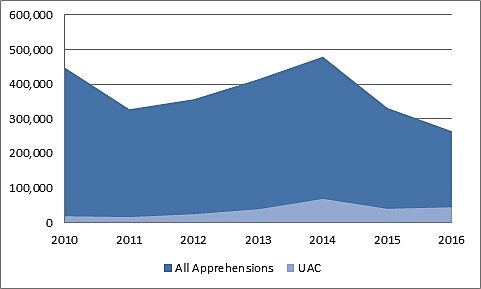

The number of apprehensions is up this year on a monthly basis. The UAC are a small fraction of the total apprehensions (Figure 2)

Figure 2

All Apprehensions and UAC

Source: Customs and Border Protection.

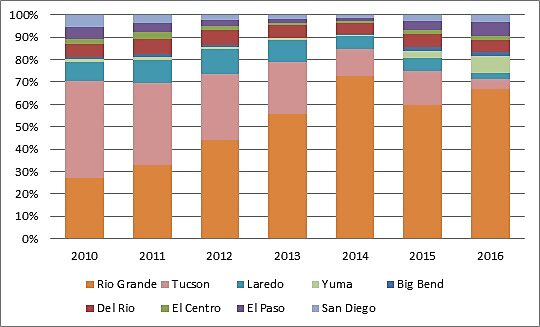

UAC apprehensions are concentrated in just a few border sectors, most are entering through Texas (Figure 3). A map of the border patrol sectors puts the flow in perspective (Figure 4).

Figure 3

UAC Apprehensions by Border Sector

Source: Customs and Border Protection.

Figure 4

Border Patrol Sectors

Source: Customs and Border Protection.

If the UAC could instead receive a worker visa or green card then they would not have to brave the difficult trip through Mexico from Central America and endure uncertainty and detention once they reach the United States. Border Patrol wouldn’t have to waste their time apprehending these folks but could instead focus on stopping actual violent and property crime. The lack of a legal immigration alternative for the UACs and their family already in the United States has created this situation. An expanded legal immigration system can fix it.

For-Profit Colleges: Terrible or Target?

The Center for American Progress has a new paper out calling for the demise of the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools (ACICS), one of the primary accrediting bodies of for-profit colleges. The paper accuses ACICS of being negligent in its accrediting practices, and as a result enabling loads of students and federal aid dollars to flow to bad schools. And ACICS may well be lax, though there is a big debate about exactly what the role of an accreditor is: college watchdog, or friendly advisor? But ACICS itself is not what I mainly want to discuss here. No, it is the evidence that for-profit schools are perhaps being unfairly targeted rather than being particularly bad actors.

The first bit of evidence is something I’ve hinted at before: lots of suits have been brought against for-profit schools, typically by state attorneys general, but few have ended in findings of guilt. As CAP’s paper helpfully itemizes, most accusations, at least for ACICS accredited schools, have been settled with “no finding or admission of fault by the college.” And in the most notable case of a court finding a for-profit guilty—the now-defunct Corinthian Colleges—the judgement was issued without a trial because Corinthian no longer existed and could not defend itself.

Many of the state AGs who have brought suits—including in California, Kentucky, and Massachusetts—have pursued higher political office. California’s Kamala Harris is running for the U.S. Senate. Kentucky’s Jack Conway unsuccessfully ran for governor in 2015. Former Massachusetts AG Martha Coakley ran for governor in 2014.

Were the suits motivated by a desire to raise the AGs’ profiles? No one but the AGs themselves knows their motivations, and they may well have concluded that the schools had intentionally done illegal things. But it is hard not to also see for-profit schools as relatively easy, unsympathetic targets. Moreover, it is possible that many schools settled not because they thought they were guilty, especially of systematic illegality, but because they did not want their names dragged through the mud anymore. In addition, unlike the AGs, they had to use their own money to defend themselves.

The CAP report also largely brushes off a contention that is crucial—but oft neglected—to understanding the seemingly poor outcomes of the proprietary sector: they work with students facing big obstacles in hugely disproportionate amounts. Writes author Ben Miller, “That argument is not necessarily accurate according to detailed reviews of literature around student default, which found that race and ethnicity do matter for default but that degree completion status is typically the strongest predictor of default.”

Of course, the abilities and personal situations of students have a ton to do with degree completion. And this is not primarily about race. Students at for-profit schools are much more likely to be African-American, but also older, low-income, and dealing with children and full-time jobs than students in other sectors, including community colleges. Indeed, a report on accreditors released by the U.S. Department of Education just yesterday reveals that among major accreditors ACICS member institutions have the highest percentage of undergraduates receiving Pell Grants, a rough proxy for income. 74 percent of students at ACICS accredited schools receive Pell, versus, for instance, 38 percent among schools accredited by the Middle States Commission on Higher Education, and 32 percent at the New England Association of Schools and Colleges.

Now, maybe the schools should choose not to work with a lot of students who face too many obstacles. But it is the federal government that gives the students much of the funding with which they pay for these schools, on the general principle that everyone should have access to college. And the feds do this without trying to meaningfully evaluate if the students are ready. So, essentially, the for-profit schools, but also the community colleges and nonselective public and nonprofit private schools, which are all seeing poor outcomes, are just doing what the feds want them to do.

Again, the evidence—all of it—needs to be considered before singling out for-profit schools for censure. Too often, it doesn’t seem to be.