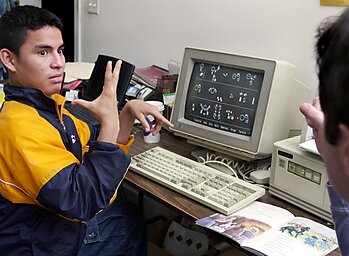

Deaf students are seen here in a classroom in 2004 at the Melania Morales Special Education Center,

where Nicaraguan Sign Language spontaneously emerged about two decades earlier.

(Photo by Oscar Navarrrete/EPA/Shutterstock)

The Spontaneous Emergence of Nicaraguan Sign Language

Whether in language, law, or commerce, lasting orders emerge from the bottom up, not from the commands of any distant expert.

Five decades ago, a group of deaf Nicaraguan children offered a striking illustration of this process when they created a language from scratch.

n 1977, a group of deaf Nicaraguan children invented their own language without any adult supervision or guidance. No adults intended this outcome, and some even tried to stop it, yet a new language spontaneously emerged. It was the result of a process classical liberals

have been describing for centuries.

Before the late 1970s, Nicaragua had no cohesive Deaf community or signed language. Most deaf people used their own set of personal signs known only to family and friends. That changed in 1977, when the Nicaraguan government founded a center for special education in Managua, initially serving 50 students and growing to enroll hundreds by the early 1980s.

Teachers at the Managua center initially focused on spoken Spanish and lipreading, not sign language, to little effect. Regardless, the school for deaf students provided a valuable place for children to interact with one another. In the schoolyard, on buses, and in the streets, children slowly found ways to communicate by combining gestures with their personal signs from home, creating a pidgin-like system of sign language now known as Nicaraguan Sign Language (NSL).

At first, the teachers were disappointed, believing the children were merely mimicking one another, and viewed their communication as a failure to learn spoken Spanish. But as time progressed, it was obvious that something unique was happening. To investigate, in 1986 the Nicaraguan Ministry of Education invited MIT-trained linguist Judy Kegl to study the children and share her findings.

Kegl observed that younger children in the school had taken the early system of rudimentary sign language and transformed it into a more efficient language. Even more astonishing was that they had introduced new features such as verb agreement and other grammatical rules that initial students lacked. These features make NSL not just a signed version of Spanish but its own full-fledged language.

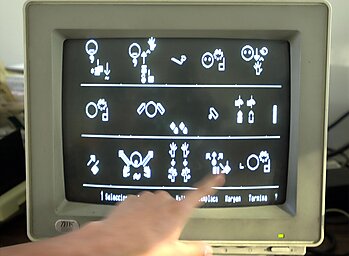

Barney Vega, a 16-year-old deaf student from Nicaragua, is seen here in 2002 working with Nicaraguan Sign Language Projects co-founder James Shepard-Kegl and University of Southern Maine student Andrew Donahue on translating a book into the language that emerged two decades earlier. (Photo by Gordon Chibroski/Portland Press Herald via Getty Images)

A new language spontaneously emerged from the minds of children and the human desire to communicate. What had occurred was an example of spontaneous order, the emergence of patterns or systems without a central planner or deliberate design. For social scientists and economists, spontaneous order is the study of the emergence of order from the actions of individuals without centralized planning or design.

It is a counterintuitive idea: How can there be order without a plan or even someone in charge? A classical liberal answer to this question is the example of language. No language has ever been effectively managed by one person or committee. Even the most essential, everyday basics of human interaction are not the creation of an explicit design formulated by particular people, but the result of generations of experience and adaptation.

By the 1990s, NSL was extensively studied by linguists and cognitive scientists worldwide. In his book The Language Instinct, psychologist Steven Pinker wrote: “The Nicaraguan case is unique in history.… We’ve been able to see how it is that children—not adults—generate language.… It’s the only time that we’ve seen a language being created out of thin air.”

Some researchers have regarded NSL as evidence that language is innate. But others, as professor of behavioral science Nick Chater and cognitive scientist Morten H. Christiansen write in their paper “Grammar Through Spontaneous Order,” believe that “the rapid emergence of complex linguistic structure in Nicaraguan Sign Language … indicates how processes of spontaneous order can arise rapidly in the absence of language-specific constraints, through the necessity to communicate.”

A new language spontaneously emerged from the minds of children and the human desire to communicate. What had occurred was an example of spontaneous order, the emergence of patterns or systems without a central planner or deliberate design.

Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language provides a striking parallel to NSL. Emerging only in the last 70 years within a small Bedouin community with a high incidence of congenital deafness, Bedouin Sign Language developed spontaneously without contact with other sign systems. Within a single generation, speakers established systematic grammar. More important, this grammar arose independently of both the surrounding spoken languages and Israeli Sign Language, demonstrating that core syntactic structures can emerge spontaneously throughout human communication.

The spontaneous emergence of NSL aligns with the classical liberal insight that social systems can develop organically without coercive direction. In the Western world, this idea was first described in An Essay on the History of Civil Society by the Scottish Enlightenment thinker Adam Ferguson in 1767. He called societal institutions “the result of human action, but not the execution of any human design,” a phrase that perfectly captures the story of NSL’s formation.

In Law, Legislation, and Liberty, F. A. Hayek also pointed to languages as the perfect example of spontaneous order, noting that they weren’t “‘invented’ by some genius of the past” but were “the outcome of a process of evolution whose results nobody foresaw or designed.”

The evolution of language parallels how a free-market economy coordinates itself through prices, not through mandates and orders. Innumerable small-scale interactions and adjustments determine prices and, eventually, order. The story of NSL illustrates the same principle. Deaf children in Managua, trying to communicate with each other, collectively invented a coherent language. Individual buyers and sellers, through self-interested exchanges, set coherent prices in markets.

Just as children evolved their communication through trial and error, entrepreneurs and consumers adjust to and innovate within markets, leading to adaptation through mutual adjustment.

Bottom-up orders, like prices and languages, are adaptive. Top-down policies are designed to be optimally efficient but rarely evolve to become better adapted to individual needs. NSL quickly adapted to its users’ needs, becoming more expressive and efficient as it evolved. Similarly, norms and institutions like money, contracts, and the division of labor evolve in market economies to better serve their participants through mutually beneficial trade. Both languages and markets are adaptive systems created by the innumerable interactions of uncoordinated actors.

The emergence of NSL is not a social miracle but a process of spontaneous order, the same general process that led to the emergence of money and global trade. Just as children evolved their communication through trial and error, entrepreneurs and consumers adjust to and innovate within markets, leading to adaptation through mutual adjustment.

Advocates of state intervention could argue that NSL arose from a form of social planning via the state’s efforts to educate deaf individuals. The classical liberal rebuttal is that the state’s role was incidental at best. Initial efforts were focused on teaching spoken Spanish and lipreading, not on creating a signed language. The state’s early reluctance to promote NSL further exemplifies it as a powerful example of an unintentional order arising when central planning fails.

Kegl’s nonprofit Nicaraguan Sign Language Projects has noted the four conditions necessary for NSL to emerge: visual access to communication, many children interacting, the necessity of communication, and a range of ages among children. NSL doesn’t prove that complex systems will always arise completely unaided, but it does show that given the right starting point, gradual self-organization is possible. NSL’s core grammatical rules took a decade to emerge. For those who lived through the process, communication was initially fragmented and incomplete.

High schooler Barney Vega discusses the nuances of Nicaraguan Sign Language with James Shepard-Kegl. (Photo by Gordon Chibroski/Portland Press Herald via Getty Images)

This lagging effect is similar to a common critique of free-market policies. Societies might eventually find an efficient order, but in the interim of adjustment, there may be short-term pains. Users of languages undergoing continual adjustment is similar to Joseph Schumpeter’s idea of creative destruction, in which entrepreneurs’ trial-and-error experimentation creates new methods of production that revolutionize the economic order of society in a way that state intervention has proved it cannot.

As a spontaneous order matures, it begins to interact with planned systems. In the case of NSL, by the 1990s and 2000s, deaf Nicaraguans were exposed to American Sign Language and other international signed languages through media and contact with the global Deaf community, influencing NSL’s growing lexicon. This mirrors how unplanned orders can later become integrated with deliberate structures. For example, many of what were once customary practices were later codified as laws by legislatures. This doesn’t negate their spontaneous origins; it illustrates the dynamic interplay of bottom-up and top-down forces.

NSL serves as a parallel to the spontaneous coordination seen in free markets, supporting Hayek’s and other classical liberals’ insights into spontaneous order. Though an inspiring example, it is not a utopian one. Real spontaneous orders may involve growing pains. The Nicaraguan Deaf community’s achievement is now part of the country’s cultural and humanistic scientific legacy as NSL continues to evolve and thrive. The experience of deaf Nicaraguans gives life and weight to the idea that we build free societies based on cooperation, not commands.