Dear Capitolisters,

With the U.S. economy heating up (even more) and more than half of American adults now having received at least one vaccine dose, it’s increasingly looking like my February optimism was warranted. Obviously, we’re not entirely out of the woods yet—especially in the handful of states that have seen recent spikes in COVID-19 hospitalizations—but the general public health trends are pretty good in most places and nationwide. And, even with the Johnson & Johnson “pause” last week and some unwelcome early signs of “vaccine hesitancy” in certain parts of the country, we’re still administering about 3 million vaccine doses per day on average, a number we could’ve only dreamed about back in February. At the same time (and doubtless related), Americans are increasingly coming out of economic hibernation, state restrictions are easing, and businesses are ramping up, if not already going full-tilt. And there’s still plenty of room to run.

Given that 2021 is looking so good, it’s a perfect time (ha) to get a little pessimistic and look at one of the non-COVID things that, while not stopping the recovery cold, might still slow it down a good bit and cause some significant strife for certain businesses and individuals in the process: the labor market.

Where We Are

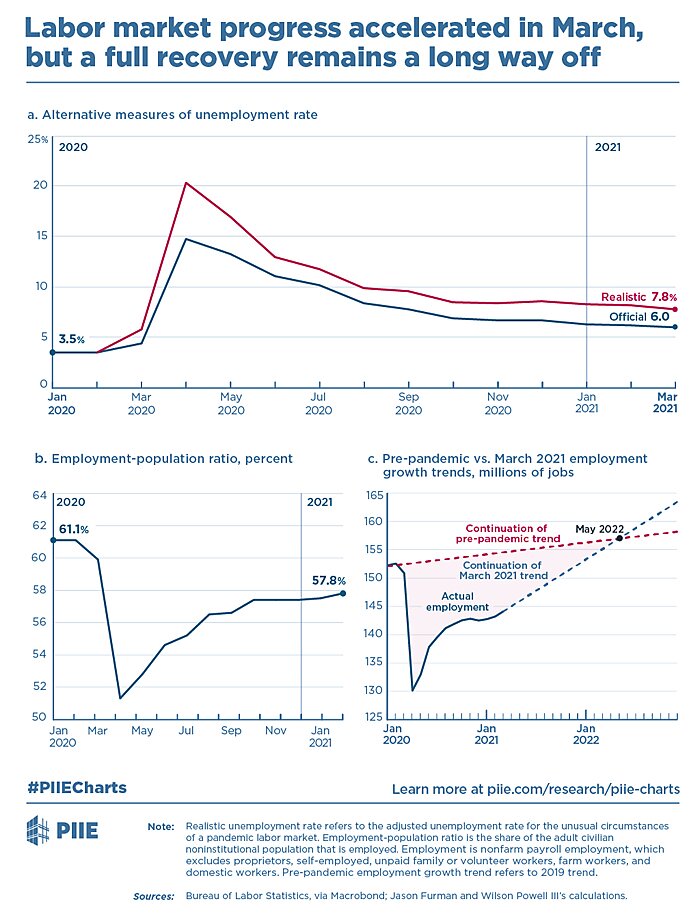

Even after last month’s jobs blowout, the unemployment rate remains significantly elevated, and as many as 10 million Americans are out of the labor force (assuming pre-pandemic trends):

I’d wager that April’s jobs numbers, which we’ll see in early May, will be as strong or stronger than the very strong March figures, which were collected before almost all American Rescue Plan benefits (including those stimulus checks) had been distributed, before tens of millions of additional vaccine doses had been administered (especially to “essential workers”), and before many states had eased pandemic-related restrictions. It’s thus quite likely that the U.S. jobs recovery has only picked up steam in recent weeks.

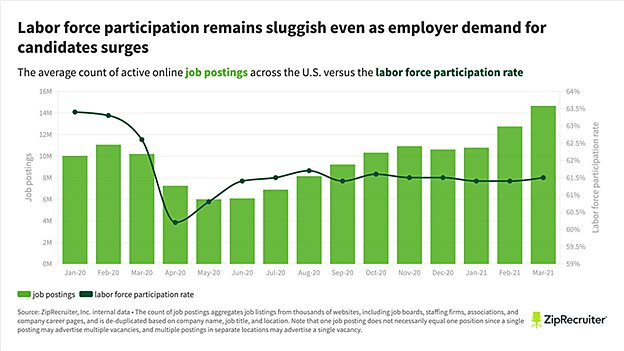

However, there do appear to be a few dark clouds on this bright horizon that might slow the recovery and put pressure on certain U.S. businesses and, in turn, the economy. Most notably (unless you’re a supply chain dork like me), numerous data points show that employers are having a hard time finding workers (job openings are at record highs), even as the U.S. labor force participation rate remains depressed:

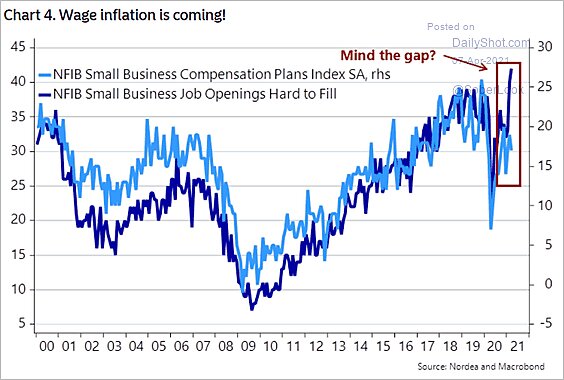

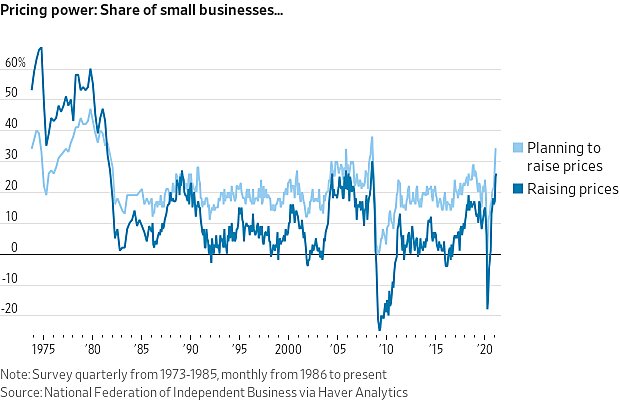

Businesses’ inability to hire workers can cause them to forego expansion, reduce output or even shut down, none of which is good (obviously) for an economic recovery. Alternatively, employers can try to attract workers with higher wages, but this approach—while surely good for those workers—can create its own headaches, most notably resulting in less hiring overall or higher prices. As we discussed a few weeks ago, for example, one recent study showed that McDonald’s franchises passed on the full cost of minimum wage hikes to customers, and recent data from the NFIB show some signs of this cycle starting during the nascent recovery (though the currently insane prices for lumber and other materials are surely contributing to these price pressures, too):

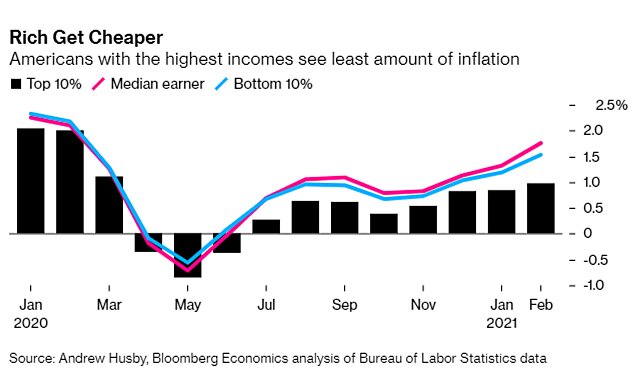

Price hikes are something we don’t really mind (within reason!) when the labor market is red hot, but they’re less than ideal with an economy just starting to heat up and 10 million people still unemployed. As Bloomberg recently noted, moreover, higher prices for certain essentials (energy, food, etc.) can disproportionately harm poorer people, even as overall inflation remains tame:

It is admittedly still early—most of the data are from March when our economic outlook was still quite uncertain (unless you were reading me, obviously)—but numerous anecdotes from April show that the March labor market issues are continuing today:

Regular checkin to how the labor market is right now… pic.twitter.com/pPq6zbCiah

— Dan Nunn (@danyay) April 15, 2021

So What’s Causing It?

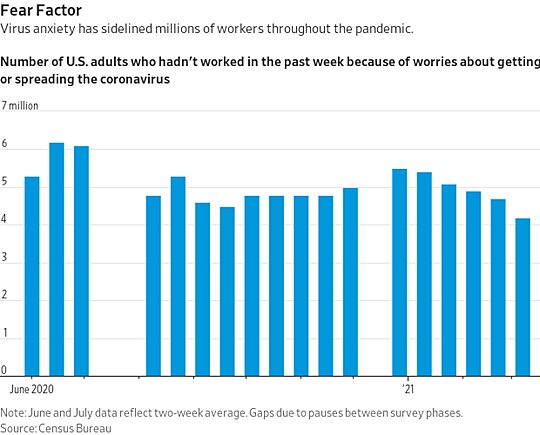

Several factors appear to be causing these issues. First, it’s undeniable that many Americans—especially those who haven’t been vaccinated yet—are simply scared to go back to work, particularly in the “consumer-facing” industries like retail and leisure and hospitality (where job openings are sky-high) or in states that are still struggling to contain the virus:

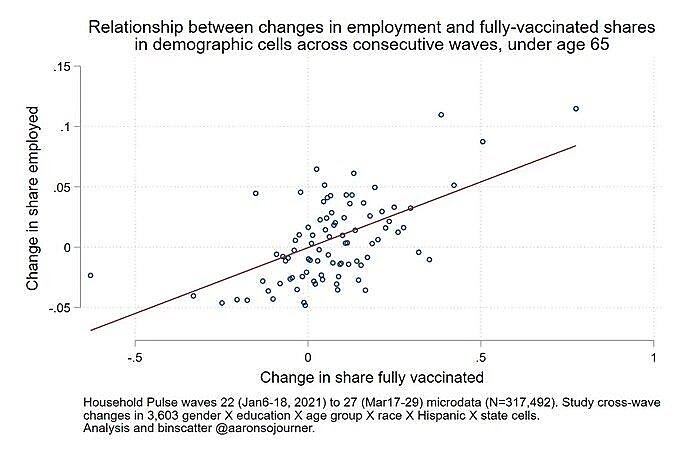

Preliminary data from economist Aaron Sojourner show a connection between vaccination rates and employment between January and March of this year:

He estimates that “a 10-percentage-point increase in the share of people fully vaccinated corresponded with a 1.1‑percentage-point increase in their employment”—possibly suggesting that “vaccinated people are more comfortable taking jobs.” Thus, as Americans get vaccinated and the most severe COVID-19 problems subside (hopefully), we should expect to see worker fears decline further and labor force participation and employment accelerate. The extent of those improvements, however, are far from clear—psychology and the virus (not to mention survey responses!) are tricky things, and there may be other factors at play (see below).

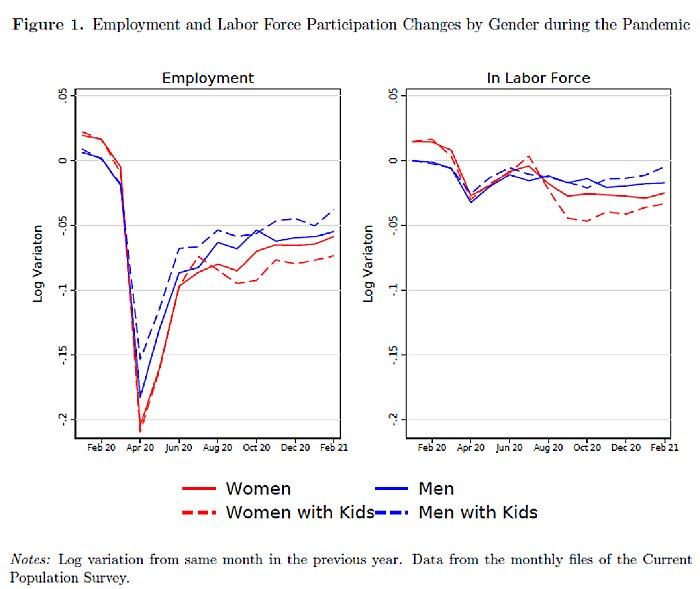

Second, new research from the Boston Fed shows that the continued closure of local schools (through February 2021) has had a disproportionate impact on working moms, keeping them out of the workforce in much larger numbers than everyone else: “While the widened gender gap for women without children started to close after the summer months, the larger gap for mothers persists. The safe reopening of in-person K‑12 education is critical for this group of women to regain employment as the economy recovers.” Here are the key charts, which show working moms’ employment and labor force participation dropping right as the 2020–21 school year started:

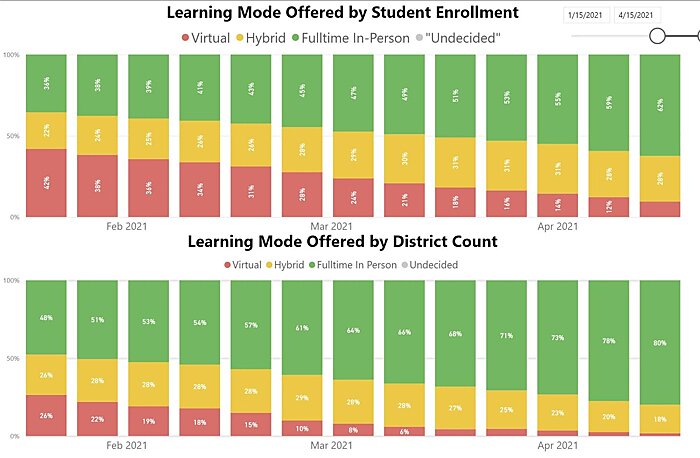

The authors optimistically conclude that “If women re-enter the labor force soon after schools reopen, the recovery in employment could be faster than in previous recessions.” However, this improvement obviously depends on schools fully reopening, and, while things have improved since February, many families are still stuck in virtual or hybrid schooling situations (especially in California):

If this situation endures, and with summer quickly approaching, many working mothers might continue to struggle to rejoin the labor market in the next few months. And the economy (not to mention those moms’ sanity!) will be worse for it.

Finally, the American Recovery Plan’s supplemental unemployment insurance (UI) benefits, which provide jobless workers with an additional $300 per week on top of their state’s benefits, may be discouraging some Americans from getting back on the job by paying them as much or more to not work than to work. According to research from the American Action Forum, at the $300 level, about 37 percent of American workers could make more on unemployment than at work, and “RBC Capital Markets chief U.S. economist Tom Porcelli calculates that leisure- and hospitality-sector workers… on average can take home about 33% more through unemployment insurance than through working.” My Cato colleague Ryan Bourne recently provided a couple concrete examples:

A low-income worker in Massachusetts previously earning $535 per week faced a pre-pandemic replacement rate of unemployment insurance benefits to earnings of 48 percent ($257). Now, the same worker would obtain benefits worth 104 percent of their pre-recession earnings ($557). In New Mexico, someone previously earning $342 per week would see a replacement rate of 141 percent from the expanded benefits ($483).

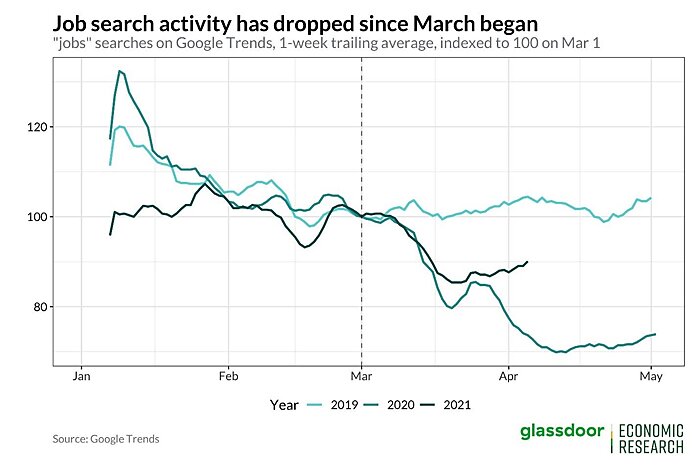

He then explains how these abnormally high benefits result in lower total employment—“The disincentive to work this creates reduces the labor supply, raising market wages but squeezing employment levels as fewer workers make themselves available for job opportunities that are economic to offer for businesses”—and cites some initial signs that certain workers are choosing this option. This includes (1) research from Daniel Zhao, a senior economist at Glassdoor, showing that job search activity on Google fell by 15 percent in early March, right before the ARP passed (see chart below); and (2) managers across the country telling the Federal Reserve’s Beige Book survey that UI was contributing to their hiring difficulties—a problem that continued in April, even as these managers raised wages. Continuing unemployment claims also have barely budged since March, even with far more vaccinations and better economic prospects, and employment among teenagers—who are less likely to be receiving unemployment benefits—has rebounded much more sharply than their older counterparts. There are also numerous new reports (including from here at The Dispatch) of employers blaming UI for unfilled job openings.

Surely, employers have an incentive to blame UI for what might be their own business failures, but economic research has repeatedly shown that expanded benefits increase the unemployment rate, while cutting them does the opposite. Studies showed this connection to be weak in 2020, but—as the virus, economic, and survey data make clear—this is most definitely not 2020. Instead, today’s labor market more closely resembles the “normal” labor markets analyzed in earlier rounds of research. It’s thus quite plausible that expanded UI is acting as a significant drag on the labor market and the U.S. economy more broadly—and could be for some time.

That said, the rapidly changing COVID-19 situation (especially vaccines) and a lot of noise in the 2021 data surely prevent us from making any definitive conclusions about how UI is affecting the U.S. labor market at the moment. If, however, we are still seeing these issues in May and June, the finger-pointing will (and should!) begin, especially since Congress had better ways to structure bonus payments and even rejected a proposal from Sen. Ron Wyden last year to turn off the UI spigot when state unemployment rates hit a certain trigger—a trigger that has already been pulled in most U.S. states:

Well I’ll be darned! The unemployment rate is high enough for $300 FPUC under the Wyden proposal in just six states. In 30 states, FPUC would be gone by now. Seems like taking the Wyden plan would have been the smart move for Republicans, in hindsight. @scottlincicome pic.twitter.com/IjKPw7kWJK

— Ryan C. Radia (@RyanRadia) April 18, 2021

Instead, we’ll be stuck with “emergency” benefits until September—long after the “emergency” has ended.

Why Not Just Raise Wages?

Some have argued that, regardless of the bonus payments’ duration, employers can easily fix the current hole in the labor market by just raising wages. This argument, however, ignores several confounding factors: First, as Bourne notes, the NFIB’s chief economist says that many small businesses already are raising wages but still haven’t had much success (so far) persuading workers to sign on. Local news stories show the same, even for jobs that pay more than $15 per hour. Second, as the New York Times explains, many of today’s job openings are in industries like retail and food service that have low profit margins, have been battered by the pandemic, and today compete against thriving companies like Amazon and Walmart that are flush with cash after killing it during the pandemic. For these companies, paying more might not be possible and, even where it is possible, they might still get outbid for an artificially scarce supply of workers. Finally, employers have to consider whether the current situation—cash-rich consumers eager to spend, a virus in remission, and American workers with plenty of leverage (including UI)—is just temporary or can justify higher wages over the longer term. (Wages are notoriously “sticky,” meaning that they’re slow to react to changes in the market, especially for currently employed workers.) Where employers aren’t certain that paying higher wages today will be profitable once the fiscal stimulus and post-pandemic euphoria wear off, then they won’t hire—or they’ll at least be very picky about whom they hire at the new, higher wage.

Or maybe they’ll just wait until UI runs out.

Summing It All Up

Despite a clear improvement in the U.S. economy, millions of Americans are out of work, and many of them just don’t appear very eager to get back to it. It’s possible that this concern is temporary and will abate quickly as vaccinations proliferate and schools reopen (or summer camps get started). Nobody really knows for sure, and they’re lying to you if they claim to. If the problem persists, however, the forthcoming economic boom will be smaller, and the summer of 2021 will be even weirder, than we’re currently expecting. And fingers will need to start pointing at unemployment benefits when we start asking why.

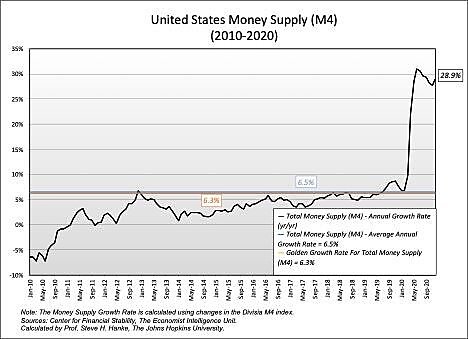

Chart of the Week

That’s quite the monetary expansion, huh? (source)

Bonus Chart of the Week

2020 accelerated Americans’ exodus from high-cost areas (source):

The Links

Me on monopolies and “globalization”

“Corporate Taxes: Rates Down, Revenues Up”

Why did nuclear power flop in the USA?

The economic case for high-skilled immigration

Creative destruction, information edition

Satellite internet must be regulated, satellite internet competitors claim

“How a Plan to Stabilize Rents Sent Prices Skyrocketing”

China demographics: still problematic

China’s digital currency: not problematic

Bilateral trade balances are (mostly) meaningless

America’s Self-Defeating Economic Retreat

California imposed brutally high taxes on weed, and you’ll never guess what happened next

What’s up with that $100 million deli?