Governments love to promise benefits. But politicians prefer not to have to raise the funds necessary to provide the promised services. The result for nationalized medical systems is political rationing … and long waiting lists. The Mackinac Institute, located in Michigan, has produced a series of videos on Canadians speaking about how their system works. The British Columbia Automobile Association even developed medical access, or wait list, insurance, before abandoning the program under pressure.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

Max Baucus’s Magic?

Max Baucus says every single Democratic senator will vote for all the taxes, all the private-sector mandates, all the inter-governmental mandates, all the Medicare spending cuts, and all the new private-insurance subsidies that he and Harry Reid are cobbling together. What’s left to discuss?

Baucus may know something I don’t. But here’s what I do know.

- To subsidize Paul, Democrats need to rob Peter. And Peter ain’t gonna like that, whether “Peter” is union members, small businesses, insurance companies, medical-device manufacturers, sick people, or the middle class broadly.

- Of course, the government already does a lot of Peter-robbing and Paul-paying in health care. Democrats could subsidize Paul #2 by cutting subsidies to Paul #1. But again, Paul #1 — whether “he” be seniors, doctors, hospitals, insurance companies, pharmaceutical manufacturers, medical-device manufacturers, home health agencies, skilled nursing facilities, etc. — ain’t gonna like that.

- Members of Congress, including Democratic senators, tend to listen to those Peters and Paul #1s.

- Democrats could try to rob future generations, but they (particularly President Obama) have painted themselves into a corner on that one by promising not to add to the deficit. And with regard to deficit spending, the public appears to be in no mood.

Heck, I’m sure that Baucus knows a lot of things I don’t know. But I doubt he knows any magical incantations that’ll make those challenges go away.

(Cross-posted at Politico’s Health Care Arena.)

Related Tags

Even Lawyers Should Be Paid More for Good Performance

Another oral argument I attended this week was in the case of Perdue v. Kenny A., in which Cato filed a brief at the end of August. The issue is whether a court can ever increase the statutorily set fees attorneys receive from the government when they successfully bring civil rights challenges to state action.

In order to enforce civil rights guarantees, Congress had two choices: either expand the Department of Justice to cover all civil rights cases, or privatize the system and allow free market principles to encourage private attorneys to prosecute violations. Congress chose the latter, creating a system of market incentives to encourage private attorneys to enforce civil rights and hold elected representatives responsible for the waste of taxpayer dollars lost in the defense of legitimate civil rights violations and repayment of “reasonable” attorney fees.

Here a group of attorneys won an important case for foster children in Georgia, and the court awarded them $6 million in fees based on prevailing hourly rates — the “lodestar” method — and an additional $4.5 million enhancement for the exceptional quality of work and results achieved. At Georgia’s request, the U.S. Supreme Court decided to review the case and determine whether quality of work and results are appropriately considered components of a reasonable fee.

Cato, joining six other public interest legal organizations, filed an amicus brief supporting the attorneys. We argue that the enhancement in this case is necessary to preserve incentives in the privatized market. Not only does it encourage attorneys to pursue civil rights abuses, but it provides a powerful disincentive for governments to draw out litigation in the hope that attorneys will no longer be able to afford pursue it. In addition, quality of performance and attained results are rightly considered as part of the attorney fee calculus. The enhancement here helps to promote the free market of privatized civil rights prosecutions and encourages governments to resolve civil rights cases quickly.

Unfortunately, the Court didn’t seem to be convinced at oral argument that there was a problem with the way civil rights attorneys are compensated under the lodestar method. Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Scalia, in particular, were aggressive in questioning a very well prepared Paul Clement (the former solicitor general, with whom I had the privilege to work on a different case that will be argued next month). They expressed concern about how to evaluate the “exceptional results” needed to justify a fee enhancement. Clement said that the Court could leave this to the trial judges’ discretion,to which Justice Scalia replied: “You say discretion. I say randomness.”

Only Justice Sotomayor, who was again an active questioner, suggested a standard to guide judges, citing such factors as a discrepancy between the market in which the attorney practices and the market on which fees are based, as well as the attoney’s experience (for example, the justices frequently referred to a “brilliant” second-year associate who might be paid at a partner rate). But several justices, at least, would never agree to such a standard. Even Justice Breyer, typically friendly to civil rights claims, expressed skepticism over whether millions of taxpayer dollars should be paid to already well-compensated lawyers.

Still, while it would be strange for district judges to have the ability to reduce fee awards for various reasons (such as inferior performance, even if technically victorious) while not being able to increase them, that’s the result we’ll have if the Court rules as all indications now suggest.

Duncan Blows Off Constitution, Facts

It never ceases to amaze me how effortlessly federal “educators” blow off the Constitution. Amazing me today is none other than U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, who in an address to the National Association of State Boards of Education offered the following cavalier dismissal of the Supreme Law of the Land:

I’d like to talk to you today about the federal role in education policy. It’s often noted that the Constitution doesn’t mention education, and that the provision of education has always been a state and local responsibility.

Yet, it is also true that American leaders have always considered education to be an important priority. They’ve always believed that a strong and innovative education system is the foundation of our democracy and an investment in our economic future.

This national commitment to education predates even the ratification of the Constitution. In the Northwest Ordinance governing the sale of land in the Northwest Territories, the fledgling government required townships to reserve money for the construction of schools.

In the middle of the Civil War, President Lincoln signed the Morrill Act to create land grant colleges and universities. Today, those institutions are some of the best teaching and research institutions in the world…

Here you see a textbook example of how you can brush off the Constitution in just a few easy steps! First, you acknowledge (actually, this part is optional) that authority over education is nowhere among the federal government’s specifically enumerated powers. Next, you shamelessly imply that all the founders really wanted power over education to be in the Constitution. After that, you always mention the Northwest Ordinance, even though it had nothing to do with the Constitution. Finally, you laud blatantly unconstitutional things other people have done and — voila! — the Constitution disappears!

Of course, making a factually or logically sustainable argument that you are not violating the Constitution when you obviously are is not the real goal here. This is just the standard political kabuki dance, a necessary bit of deference-payment to those few rubes who might still think that the Constitution serves some legitimate purpose.

That said, don’t you expect more from our secretary of education? After all, he has undertaken the incredibly noble job of teaching all of our children. Don’t you expect complete honesty from him, and maybe even some respect for the Constitution that he has taken an oath to uphold?

Of course you don’t. Neither do I — not one bit.

U.S. Standing in the World

Well before Barack Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, Americans were speculating on whether his ascendancy to the highest office in the land would help to improve the United States’ tarnished reputation in the world.

The early indications were encouraging, but largely anecdotal. The Pew Research Center provided data from surveys taken in May and June, and found a mixed picture: attitudes toward the United States were most improved in Western Europe, East Asia, and Africa (Nigeria and Kenya), but barely changed in the several predominantly Muslim countries polled, including U.S. allies Turkey and Pakistan.

The more relevant question is whether we should care. International relations is not a popularity contest. In the classical formulation, nation-states pursue policies that they believe will advance their interests. Sometimes these policies backfire. Sometimes they fail. But, all other factors being equal, we should assume that policies are directed from within, and not much influenced by without.

A recent study published by the American Political Science Association makes a reasonably convincing case that Americans should care about U.S. “standing” not purely for the sake of feeling good about ourselves, but also because improved standing is likely to contribute to more effective foreign policy. “Diminished standing may make it harder for the United States to get things done in world politics,” the report explains. In this context, the report continues, we should “think of standing … as the foreign-policy equivalent of ‘political capital.’ ” If we have a stored reserve of such capital, we can deploy this to mobilize international support. At a minimum, this will convince other countries to go along with us; in ideal cases, we might obtain their active support.

The report was commissioned by the outgoing APSA president, Peter J. Katzenstein of Cornell University, and the task force was chaired by Jeffrey Legro of the University of Virginia, and included a number of eminent scholars. [The full report is available here, a shorter public version was made available here, and Katzenstein and Legro summarized the findings in a recent article at Foreign Policy.com.]

For the sake of argument, I will concede that America’s reputation is a factor in the extent to which other countries support or oppose our policies, and therefore that it is worthwhile to attempt to bolster our reputation. But the report inadvertently shows that, in practice, even concerted effort by policymakers and opinion leaders to improve U.S. standing is likely to fail, largely because of deep contradictions between what others expect of Uncle Sam, and what Americans expect from our government and from others.

Generally speaking, non-Americans like the United States playing the role of world policeman — provided we do the job well. If the U.S. military deters aggression against small or weak countries, those countries won’t have to devote resources to defending themselves. Oppressed people often welcome U.S. pressure on the autocratic regimes that are oppressing them; some disenfranchised people welcome U.S. government efforts to give them some say in how they are governed, and by whom.

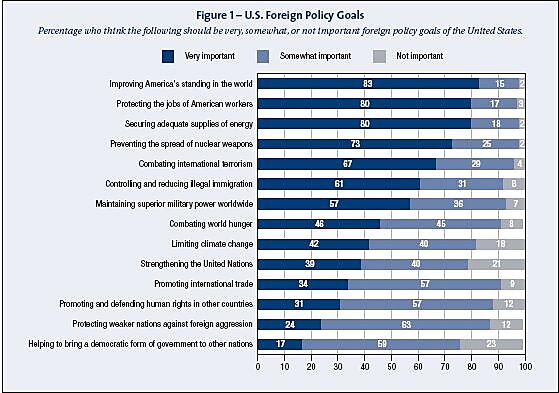

If the opinions of non-Americans were decisive in the formulation of U.S. policies, then we might be able to do all of these things. But they are not. In a list of 14 foreign policy goals polled by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, Americans rank “Promoting and defending human rights in other countries” and “Protecting weaker nations against foreign aggression” 12th and 13th, respectively. As far as democracy promotion goes, that falls dead last on the list; a mere 17 percent of respondents thought this a “very important” goal for the U.S. government.

Despite public skepticism toward these goals here in the United States, non-Americans can be forgiven for believing that the U.S. government exists to do such things for them. After all, the notion that the United States should be the primary provider of global public goods has guided U.S. foreign policy for decades, and almost always in the face of strong opposition to such philanthropic impulses.

As I explain at length in my book The Power Problem, the disconnect between what the public wants, and what the policymakers give them, is deliberate and by design. Most of the people in Washington dismiss public attitudes as misinformed at best and isolationist at worst. But while I agree that we should not conduct our foreign policy on the basis of polls and focus groups, in the grand scheme, the hand-waving and misdirection that our leaders have employed since the end of the Cold War to conceal and distort the true costs of our current grand strategy is, well, unseemly.

Michael Lind has a better word for it: “Nothing could be more repugnant to America’s traditions as a democratic republic,” he writes in The American Way of Strategy, “than a grand strategy that can be sustained only if the very existence of the strategy is kept secret from the American people by their elected and appointed leaders” (my emphasis).

I wholeheartedly agree. In a country that presumes some measure of popular consent, the current pattern is repugnant.

So what does this mean for improving American standing? If the rest of the world wants the United States to be the world’s cop, social worker, and election monitor, but Americans expect our government of limited, enumerated powers to do these things only when U.S. national interests are at stake (and they rarely are), is this the counsel of despair?

Not necessarily. There is another way in which the United States could improve its international standing without having to go out of its way to convince others of our good intentions, and without systematically concealing from the American people the true object of our foreign policies.

As formulated by the APSA task force, “standing” consists of two elements, “credibility” — “the U.S. government’s ability to do what it says it is going to do” — and “esteem” — which “referes to America’s stature, or what America is perceived to ‘stand for.’ ” The right-leaning members of the academy, including George Washington University professor Henry Nau and Stanford’s Stephen Krasner, who submitted a spirited dissent from the report, question the importance of esteem. Tod Lindberg echoed these sentiments in comments at the National Press Club several weeks ago, at the time of the report’s public release.

I think it goes too far to say that esteem is essentially irrelevant, but I agree that credibility is the more important of the two. As such, it is crucial to fashion policies that are consistent with the wishes of the American people, and that can be sustained in the face of difficult circumstances and potentially high costs.

This means we need a new grand strategy. We could drop the revolutionary impulse behind our foreign policies, declaring ourselves content with the international status quo, and therefore not an imminent threat to any other country or people that respects our rights and liberties. We could likewise disavow any attempt to overthrow the established social order in foreign lands, and reaffirm our respect for sovereignty under international law. Finally, and most importantly, we could reestablish our international reputation by keeping our promises, and that would begin by not making promises that we can’t — and have no intention to — keep.

I will have more to say about that last point at a discussion next month hosted by the Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation at the University of California’s Washington Center. To learn more, visit their website.

(C/P from the Partnership for Secure America’s Across the Aisle)

Related Tags

Is Michelle Obama Right about Teachers?

First Lady Michelle Obama wrote yesterday in US News and World Report that we face a teacher shortage. She laments that up to a third of current teachers could retire in the next four years. The solution, she says, is to embark on an aggressive and multifaceted teacher recruitment campaign.

But here’s an interesting thought: What if a million teachers really did retire in the next four years, and we only replaced half of them?

Catastrophe? Millions of kids without teachers? Nope. In fact, we’d still have a lower pupil/teacher ratio than we did in 1970. Back then, we had 2 million teachers for 45.5 million students. Today, we have 3.2 million teachers for not quite 50 million students.

For the past 40 years, we’ve added teachers a lot faster than we’ve added students. In fact, we’ve added other staff even faster. As a result, the total staff to student ratio has gone up by nearly 75% since 1970.

There are plenty of critical problems with American education, but a looming crisis in the size of the teaching workforce is not one of them.

Related Tags

Czech Support for Klaus at 65%

According to press reports, the most recent opinion poll shows that 65% of Czechs support President Václav Klaus’ refusal to sign the Lisbon Treaty that would take more power from national parliaments and give it to the unelected bureaucracy in Brussels.

Klaus, who has been at the pinnacle of Czech politics for the last 20 years (as minister of finance, prime minister, speaker of the house and now as president), has an unmatched understanding of the Czech people. Clearly, once again, he was able to discern the public mood better than others. That includes his successor as the leader of the center-right Civic Democratic Party (ODS), Mirek Topolanek, who once opposed the Lisbon Treaty but now supports it. It seems that the ODS is in a state of revolt against him and may unseat him at the ODS Party Congress in November.

Klaus will be much encouraged by the above poll. As a consequence, it is less likely that he will give way under pressure and sign the Lisbon Treaty anytime soon. If he can hold out until the likely British referendum on the Lisbon Treaty midway through 2010, he will likely be remembered as the man who put an end to the most ambitious attempt to create a centralized European super-state in modern history.