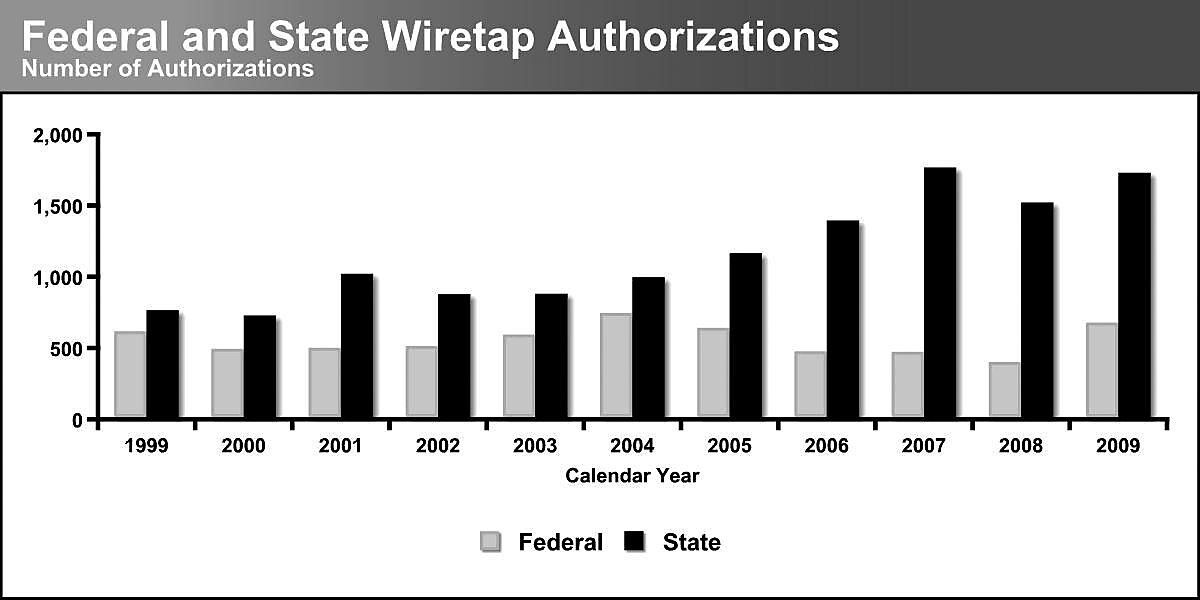

The 2009 Wiretap Report has just been released by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. The headline findings: 2,376 wiretaps were authorized for criminal investigations last year, of which 663 were federal and 1,713 were issued at the state level. (NB: These numbers don’t include Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act wiretaps, “pen register” requests for communications metadata, or orders to acquire stored e‑mails sitting on a server.) The vast majority of wiretaps—86 percent—were part of the drug war, with the average wiretap bill running about $52,200.

In line with recent years, only about 19 percent of intercepted communications contained anything incriminating. As you can see by eyeballing the chart, the 2009 numbers reflect a sharp 70 percent increase in federal taps over the previous year, but only because 2008 was a decade low-point. Though the number is still relatively high, criminal federal wiretap warrants were long ago eclipsed by broader and more secretive intelligence wiretaps under FISA—of which there were 2,082 in 2008.

Since drug dealers seldom have fixed offices, it probably won’t come as any surprise that 96 percent of the orders targeted mobile devices. Since a full wiretap order also permits the acquisition of the highly detailed GPS information phones can provide, it would be nice to know how many of these orders involve the use of a cell phone as a mobile tracking device. There’s a campaign underway to update our grossly outdated surveillance laws, and better reporting on this relatively novel form of surveillance should be part of a larger geotracking reform providing a single process and a single clear standard for seeking such information, rather than the patchwork of warrants and other sorts of court orders currently employed.

As another data point for the need to reform federal surveillance law, only four of last year’s orders involved any kind of “electronic communication,” as opposed to traditional voice communications. Does that mean law enforcement agencies are just ignoring the Internet? Of course not. But current law, perversely, establishes a much higher standard for the interception of “live” communications in transit over the network than for e‑mails that have landed on a user’s server. As soon as you open that e‑mail, the level of protection it’s afforded by statute is radically diminished, and the constitutional protections given to stored emails are still embarrassingly unclear, at least as far as the courts are concerned.

The irony here is that the outdated federal surveillance laws actually leave us hard pressed to accurately gauge how badly they’re outdated. The primary problem is that the crazy-quilt of statutes and standards doesn’t map the way people actually communicate today, or line up with their real-world expectations of privacy in those communications. But the secondary problem is that the reporting requirements don’t line up either. I’m probably a little abnormal here, but I communicate via e‑mail, Twitter, or IM vastly more than I talk on the telephone. I send dozens of e‑mails on an average day (many from a GPS-enabled phone), but I doubt I average more than one actual voice phone call per week. There are, of course, many reasons to expect criminals to prefer the ephemeral nature of voice communication, but the disconnect still ought to be worrying. The numbers in the Wiretap Report make us feel as though we have a handle on the scope of government surveillance, when in fact we probably don’t have a very clear picture at all.