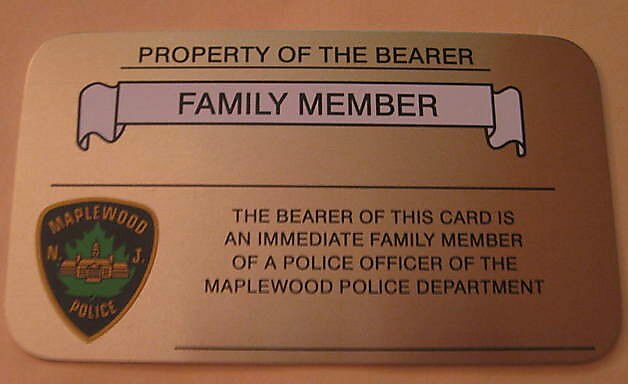

I recall quite vividly the day I first witnessed the potency of the “get out of jail free” cards issued by Police Benevolent Associations. I was a teenager in the New Jersey suburbs headed to a concert with a car full of friends, and our driver was so caught up in conversation about what a great show it was going to be that, despite our feeble warning shouts, he barrelled through a solid red light going about 40 miles per hour—a red light with a police car stopped on the opposite side of the intersection. Predictably, the police car immediately flipped on its siren and tore after us. The passengers resigned ourselves to missing the start of the show. At the very least we were going to be stuck waiting through a sobriety test. The driver was surprisingly calm. He explained that he had both a card and a silver shield in the rear window identifying him as a family member of a law enforcement officer. To our astonishment, the stop was the shortest I’ve ever sat through before or since. The officer made some small talk with the driver, asked (without checking) whether his record was clean, then apologized for the delay before sending us on our way. As our friend explained on the way to the show, an ordinary paper card—the sort given to friends of police or folks who’ve made a donation to a PBA—would have been torn up after such an encounter, providing immunity for only a single minor infraction, while the family versions were permanent.

Since I don’t own a car, I hadn’t thought about these in years, until a story in the New York Post—about officers livid that the union was cutting their allotment of cards to distribute—provoked a flurry of discussion on social media. Readers who’d never heard of the practice before reacted with shock that this form of petty corruption could be so normalized that there would actually be official cards, openly distributed by police departments or their unions, for the explicit purpose of placing friends, family, and donors above the law—even if only for relatively minor infractions. The idea that family of police might get more lenient treatment was not particularly surprising, but many seemed taken aback that the practice could be so shamelessly institutionalized on such a large scale. Is there, after all, any conceivable non-corrupt reason for issuing wallet-sized cards identifying the bearer as a relative of police?

That sense of shock was, I immediately recognized, the correct reaction. As long as laws are enforced by human beings, a bit of small-scale local nepotism in the enforcement of the law is probably unavoidable. But there is something quite toxic about institutionalizing it, to the point where officers feel so entitled to special treatment for themselves and their friends and family that they express open outrage when the law is applied to them as it would be to any other citizen. Getting out of a speeding ticket may not seem like a dire threat to the rule of law—though you do have to wonder how many cardholders feel emboldened to drive intoxicated—but I think one can reasonably draw a link between this sort of petty favoritism and the more serious abuses that leave so many minority communities regarding their local police less as public servants than an occupying force.

Think about the message these cards send to every officer who’s expected to honor them. They say that the law—or at least, some ill-defined subset of it—isn’t a body of rules binding on all of us, but something we impose on others—on the people outside our circle of personal affection. They say that in every interaction with citizens, you must pay special attention to whether they are members of the special class of people who can flout laws, or ordinary peons who deserve no such courtesy. They say that, at least within limits, officers of the law should expect to be able to break the law and not be punished for it. They say that a cop who has the temerity to hold another officer or their family to the same standards as everyone else is a kind of traitor who should expect to suffer dire consequences for the sin of failing to respect that privileged status. Moreover, they say that this is not merely some unspoken understanding—a small deviation from impartial justice to be quietly tolerated—but a formalized policy with the explicit support of police leadership.

Can we really be surprised, when a practice like this is open and normalized, that the culture it both reveals and reinforces has consequences beyond a few foregone speeding tickets? Should we wonder that police fail to hold their own accountable for serious misconduct when they’re under what amounts to explicit instructions to make exceptions for smaller infractions on a daily basis?

There is a popular approach to policing known as the “broken windows theory.” The theory encourages local governments to prioritize enforcement of minor “quality of life” laws, on the premise that when small violations of the law (such as petty vandalism) are visible in a neighborhood, it encourages more serious forms of lawbreaking. Punishing litterbugs and graffiti artists, on this line of reasoning, is important less because graffiti and litter are inherently great harms, but because they contribute to a sense of social disorder and lawlessness that encourages potential malefactors to think, if only subconsciously, that assaults and robberies are also unlikely to be punished. Criminologists continue to debate the validity of the theory and the magnitude of its effects, but whatever signal a broken window sends, it must surely be weaker than an overt policy that makes some laws applicable only to the little people.

Policies like this survive, of course, because they’re hugely popular with police and their families, while not imposing an obvious burden on everyone else. Nobody likes getting a speeding ticket, but few are going to muster too much outrage that the deputy’s spouse didn’t get one. But beyond being an affront to the ideal of the rule of law in the abstract, it seems plausible that these “get out of jail free” cards help to reinforce the sort of us-against-them mentality that alienates so many communities from their police forces. Police departments that want to demonstrate they’re serious about the principle of equality under the law shouldn’t be debating how many of these cards an average cop gets to hand out; they should be scrapping them entirely.