By the start of 1948, there could no longer be any doubt: the Great Depression wasn’t coming back. Instead of collapsing at war’s end, as many feared it would, combined government and private spending (as measured by nominal Gross Domestic Product) hardly budged between 1945 and 1946, and started climbing again thereafter. Consequently, as we’ve seen, the unemployment rate ended up being as low as it had been in the latter 1920s; and the consumer price level, far from falling again as many feared it would, rose at alarming rates once controls were lifted, settling down by the end of the decade.

Nor was this postwar improvement short-lived: a decade later, Brookings economist Bert Hickman (1958, p. 117) was able to commemorate twelve years of “impressive” growth “unmarked by serious economic contraction.”

Missing the Mark

What lay behind this remarkable achievement? The proximate answer was a revival of private spending far exceeding what many economists, and Keynesians especially, predicted, and doing so by more than enough to compensate for a reduction in government spending that was itself greater than most had anticipated.

Consider, for example, a pair of painstaking and influential but otherwise representative forecasts prepared just after V‑J Day by Everett Hagen, who was then chief of the Fiscal Policy and Program Planning Division of the Office of War Mobilization and Reconversion. Despite the late date, and the fact that Hagen somewhat overestimated postwar government spending while underestimating the pace of demobilization, his “more favorable” forecast underestimated 1946 GNP by about 12 percent, mainly by underestimating both consumer spending and private capital formation. Hagen’s “less favorable” forecast underestimated 1946 GNP by more than 15.5 percent. Both forecasts put the number of unemployed at 8.1 million during the first quarter of 1946, overestimating it by more than 5.5 million. But while the more favorable one had the unemployment level dropping steadily to 5.6 million by mid-1947, the less favorable one had it increasing to 9.3 million—an overestimate of almost 7 million!

Looking back, at the end of that decade, on Hagen’s forecast and others like it, Bureau of the Budget economist Michael Sapir observed that

we forecast deflation, deficiencies of demand, a tendency for prices to fall, sizable unemployment, a rather bearish mood in the business world. Instead, inflationary pressures have been constant and general: prices and wages have risen, incomes are at record levels, sustaining demands far above available supplies; employment, after the first shock on the munitions industries has been high, and in no month since V‑J Day has unemployment been more than 2¾ million.

So much for what happened. The $64,000 question is, why didn’t the reduction in government spending lead to an overall decline in spending, and corresponding unemployment? What caused private spending to grow enough to make up for that decline, after having been at low levels for so long?

Automatic Stabilizers?

Before we can answer that question, we must address claims to the effect that private spending wasn’t really what kept the postwar economy humming. Some economists have insisted that, despite appearances, the federal government was still propping up the U.S. economy in the years that followed the war. According to Alan Sweezy (1972, p. 122), like some fake perpetual motion machine running on well-hidden batteries, what appeared to be a largely private-market economy capable of sustaining itself and even growing was in fact an economy still dependent upon government support. Alvin Hansen’s concern about chronically deficient private spending was, in other words, correct after all.

“What Hansen said,” Sweezy writes,

was that we could not get full employment, except in temporary spurts, if government expenditures did not play a larger role in the economy. Since larger meant larger than before the depression, when the federal government’s expenditures on goods and services were about 6 percent of GNP, one can hardly prove him wrong by showing we have had full employment with government purchases at several times that percentage.

Harold Vatter (1985, pp. 151–2) also attributes the lack of a severe postwar slump to increased government spending. Provided one allows for “large and growing state and local expenditures,” he says, “civilian and military [federal government] expenditures…were sufficient to maintain a generally high level of employment and to avoid a severe recession.” As Brad De Long (1996, p. 43), points out, if it did nothing else, the 1946 Employment Act symbolized the end of attempts to keep government budgets, and the federal government budget especially, balanced during cyclical downturns. Instead, “automatic stabilizers,” meaning increased deficit spending solely due to fallen revenues and increased relief payments, were allowed to operate. The greater the overall scale of government spending, the greater the potential contribution of these stabilizers.

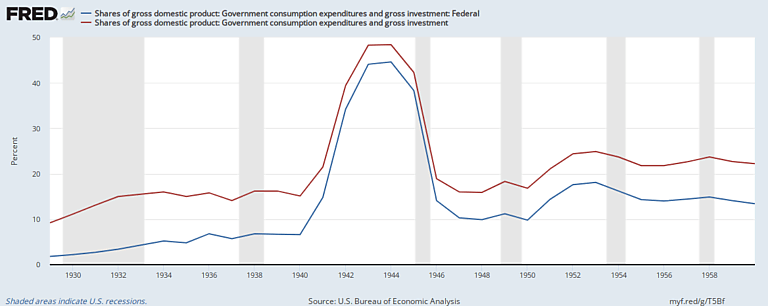

But the actual record of government spending on all levels before and just after the war, as shown in the following chart, suggests that, while growth in the size of government may account for later gains in stability, it can’t have made much difference during the immediate postwar era. In those days, the federal government’s share of GDP, instead of being “several times” larger than its prewar level, was only one-and-one-half times as large, while the share of GDP consisting of spending by all levels of government had scarcely risen at all. The small difference—that between a range of 16–19 percent versus one of 14–16 percent—hardly seems capable of accounting for the difference between depression and prosperity!

The federal government’s share of GDP grew further during the 1950s, reaching more than twice its depression-era level by 1958. So perhaps by then the U.S. economy was “inherently more stable” than that of the 1930s (Hickman 1958, p. 118). But after investigating this possibility, Hickman (1958; 1960) concluded that, although the federal government was certainly capable of combating a recession through deliberate fiscal policy actions, it still wasn’t big enough for automatic stabilizers to have accomplished much. Indeed, whether automatic stabilizers ever succeeded in making the postwar economy significantly more stable than the pre-Great Depression economy remains controversial (DeLong 1996, p. 47).

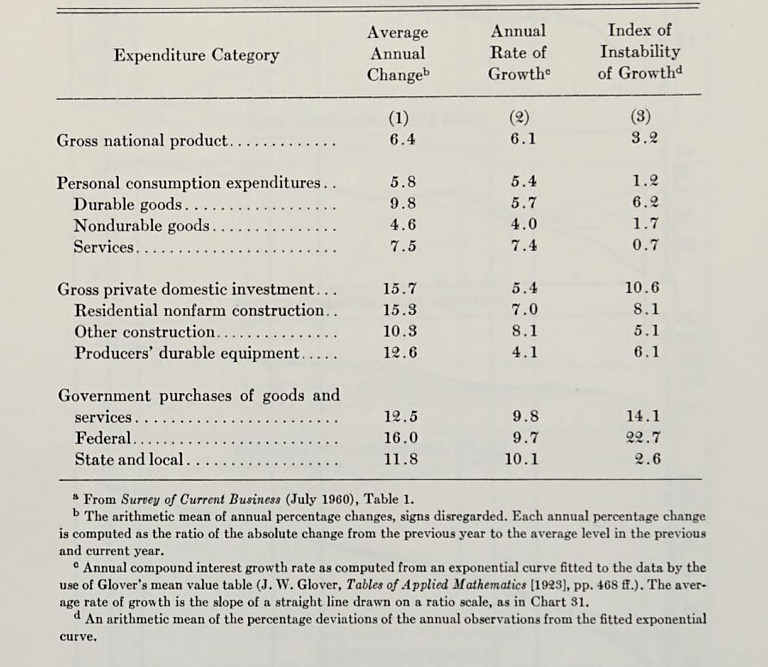

As for deliberate fiscal policy actions, these proved far less helpful in fact than in theory. In fact, postwar federal spending was the least stable of “all major categories of final domestic demand during the postwar years” (Hickman 1960, p. 209). Here is Hickman’s table (ibid., p. 212) comparing the stability of various components of postwar spending:

Had the “oscillations” in federal spending been calculated to offset opposite changes in private-sector spending, and investment spending in particular, they might still have been stabilizing. But despite the 1946 Employment Act, instead of reflecting “basically Keynesian behavior,” as John Modell (1989, p. 219) and many others suppose, the ups-and-downs of federal spending then mainly reflected changes in perceived defense needs. So instead of limiting “such short-term instability as has occurred” (Hickman 1958, p. 128), they were often its chief cause; and when increased government spending did serve to counter downturns, as happened in 1949, it mostly did so fortuitously.[1] “If big government is regarded as a structural feature of the economy,” Hickman cautioned, (1958, p. 129), “the fact that the overwhelming bulk of federal purchases of goods and services is for national security and may therefore shift up or down with changes in the international or military situation must also be accepted.”

Another point Hickman makes is that long-term growth in the government’s share of total spending mainly served to offset a corresponding decline in the consumer spending share, leaving the potentially far more volatile contribution of private investment as capable of causing trouble as ever. “Even if it is assumed that a pronounced curtailment of government spending is not likely to recur for some time to come,” Hickman observes (ibid.), “it must be recognized that private investment is still sizeable enough to fall as far below its full employment share of GNP as it did after 1929.”

In short, Hickman concludes, “[i]t cannot be maintained…that the potential range of private autonomous demand had been radically diminished by the growth of federal expenditure.” Although the federal government’s increased relative importance “augmented economic stability in some respects,” it also “diminished it in others,” the result being, at best, a wash. It follows that, if the government really did make the postwar economy more stable than the prewar one, it did so, not simply by growing larger, or by actively countering fluctuations in private spending, but by dint of other beneficial policies (ibid., p. 236).

Pent-Up Demand

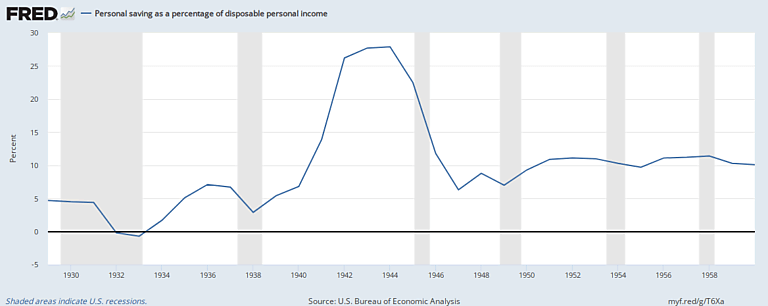

Before we inquire into these other policies, it will pay to take a closer look at the postwar revival of private-sector spending, starting with consumption. Government economists had simply assumed that what had been a simple prewar relation between private disposable income and consumption expenditures before the war would continue to hold in the immediate postwar period. Instead, as we’ve seen, postwar consumption spending proved to be much greater than they’d forecasted. In making that assumption, they failed to consider what one astute academic economist (O’Leary 1945, p. 37) recognized as “powerful new factors” that had come into play during the war, by far the most important of which consisted of the rationing, if not the complete lack, of all sorts of consumer goods. That many goods, and durable goods especially, weren’t available during the war, was hardly a secret. But the economists assumed that, whatever consumers couldn’t spend on autos and refrigerators they’d instead spend on clothing, liquor, and other nondurables.

To say that they were mistaken would be a gross understatement. Far from keeping up with disposable income during the war, consumption as a share of income nosedived, while the personal savings rate shot up. “Instead of ‘spilling-over into nondurable expenditures,” Michael Sapir (1949, p. 303) writes, money that couldn’t be spent on durable goods “flowed into…liquid assets such as currency, bank deposits, and federal government securities,” including war bonds. The government for its part encouraged workers to buy those bonds by appealing to their patriotism while arranging to have the bonds paid for through payroll deductions (Brunet and Hlatshwayo 2022, p. 29). As can be seen in the next chart, by D‑Day the public was saving almost 30 percent of its post-tax income, as compared to less than 5 percent in 1929.[2]

When the war ended, the public, having practiced abstinence for several years, was sitting on more than $150 billion worth of highly liquid assets, with a matching urge to start shopping (Higgs 1999, p. 607). With many durable goods still hard to come by at first, the public—and returning veterans especially (Sapir 1949, p. 318)—at first went on a nondurable-goods spending spree. But eventually, as controls were lifted and reconversion made durable goods increasingly available, demand for them also rose enough to keep their producers in the black, and to make jobs available for most former defense workers and demobilized military personnel who wanted them.

Yet it wasn’t the case, as some economic historians have assumed, that Americans drew down their wartime savings to pay for all those goods. Instead, as Bob Higgs (1999, pp. 607–09) has pointed out, and as the last chart shows, although the public reduced its savings rate after the war, on the whole it didn’t actually dissave at all. “On the whole,” Michael Sapir, 1949, p. 613) observes, citing a careful Federal Reserve study, “families did not intend and did not want to spend their liquid assets in 1946 on such things as automobiles, refrigerators, and consumer goods generally.” Instead, “people preferred if possible to buy out of income, or perhaps borrow on short-term.”[3] In fact, although they no longer piled-up savings as they had during the war, Americans saved as much, and eventually more, than they saved in the ’30s, or even in the 1920s. By 1950 the savings rate was more than twice its pre-depression level; and it would never fall any lower until the mid-1980s.

The Investment Revival

That Americans were both consuming more and saving more after the war than they had before it, and were doing so despite huge cutbacks in government spending, could only one thing, namely, that businesses were doing their part—a much bigger part, presumably, than before the war—to buoy up the postwar economy.

And so they were. The postwar investment revival, or whatever forces were behind it, was arguably the most important of the “powerful new factors” driving U.S. economic activity during the postwar era. “In current dollars,” Higgs (1999, p. 609) observes,

gross private domestic investment leaped from $10.6 billion in 1945 to $30.6 billion in 1946, $34.0 billion in 1947, and $46.0 billion in 1948. Relative to GNP, that surge pushed the private investment rate from 5.0 percent in 1945 (it had been even lower during the previous two years) to 14.7 percent in 1946 and 1947 and 17.9 percent in 1948. As a standard for comparison, one may note that the investment rate had been nearly 16 percent during the latter half of the 1920s, before hitting the skids during the depression.

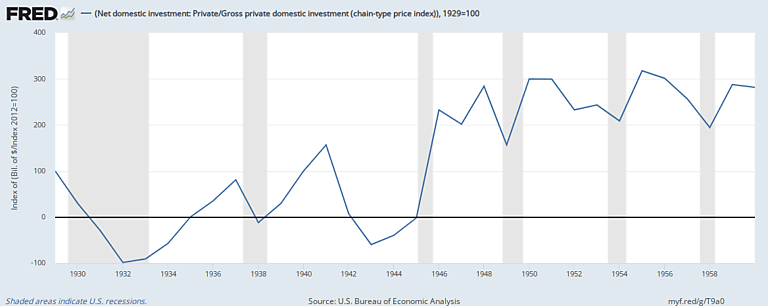

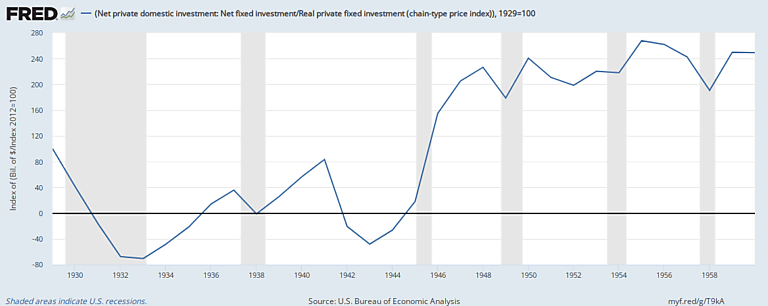

Impressive as the upturn of gross investment was, the revival of net investment, which is what actually fuels economic growth, was still more so. “Revival” is the right word, because as the next chart shows, for most of the 1930s, and again while the United States was at war, net private investment gave way to private capital consumption. Having plunged deep into negative territory before Roosevelt took office, private net domestic investment recovered somewhat before dropping to zero again during the ’37 downturn. A second recovery began in 1938, only to be halted by America’s entry into the war. Finally, after V‑J Day, it leaped back to life, swaying thereafter between two and three times its 1929 level until the 1960s, when it began rising even higher.

But the most striking change of all was to net private fixed investment, that is, private-sector spending on structures, equipment, and production inputs other than raw materials. Fixed investment differs from total private investment in excluding changes to firms’ stocks of unsold goods, or inventory investment.” Although inventory investment is often deliberate, in which case it’s no less a sign of business buoyancy than investments of other sorts, it can also be an unwanted result of falling demand (Khan 2003). Low inventories may, on the other hand, be a sign of recovery.[4] For this reason, the extent of net fixed private investment can be a more reliable indicator of both the progress of economic recovery and investment’s contribution to it.

To judge by this indicator, as tracked in the next chart, recovery made very little progress during the New Deal compared to the tremendous leap it took just after the war. Even the fillip given to American manufacturers by Europe’s mobilization never managed to raise real net private fixed investment much beyond 80 percent of its 1929 level. In 1947, it was more than twice as high.

Economists have long understood that “business cycles are mainly about fluctuations in private investment” (Martin 2016; compare Gordon 1955, p. 23), that severe downturns inevitably involve a collapse in such investment, and that self-sustaining recoveries after such downturns, with robust real economic growth, are only possible if private investment itself recovers. Expansionary monetary and fiscal policies unaccompanied by such a recovery can equip people with money to offer for goods. But they alone won’t deliver the goods.[5] In a very fundamental sense, the postwar revival of private investment was not just a sign that the U.S. economy had recovered. It was the very essence of recovery.

But what was behind it, and why hadn’t it happened sooner?

Continue Reading The New Deal and Recovery:

- Intro

- Part 1: The Record

- Part 2: Inventing the New Deal

- Part 3: The Fiscal Stimulus Myth

- Part 4: FDR’s Fed

- Part 5: The Banking Crises

- Part 6: The National Banking Holiday

- Part 7: FDR and Gold

- Part 8: The NRA

- Part 8 (Supplement): The Brookings Report

- Part 9: The AAA

- Part 10: The Roosevelt Recession

- Part 11: The Roosevelt Recession, Continued

- Part 12: Fear Itself

- Part 13: Fear Itself, Continued

- Part 14: Fear Itself, Concluded

- Part 15: The Keynesian Myth

- Part 16: The Keynesian Myth, Continued

- Part 17: The Keynesian Myth, Concluded

- Part 18: The Recovery, So Far

- Part 19: War, and Peace

- Part 20: The Phantom Depression

- Part 20, Coda: The Fate of Rosie the Riveter

- Part 21: Happy Days

_________________________

[1] Although the federal government’s response to the 1949 downturn is often considered a successful test of Keynesian fiscal policy, to even describe it, as Benjamin Caplan (1956, p. 27) (one of the CEA’s own economists from that period) has, as “a limited test with very mixed results,” is being generous. As Caplan himself notes, until well into 1949, the CEA’s chief concern was not recession but inflation. Consequently Truman, acting on the Council’s advice, repeatedly pressed an anti-inflationary program on a reluctant, Republican-controlled Congress. Just when Truman finally managed, in July 1948, to get Congress to impose some anti-inflationary measures, the boom tapered off. “It was,” Caplan (ibid., p. 37) says, “a case of locking the barn after the horse was stolen.”

From then on, the signs of a weakening economy became increasingly evident. Yet the CEA continued to be concerned about inflation, and Truman kept calling for more measures to counter it, even after the ’49 downturn began (ibid., p. 38). Although it’s true that expansionary fiscal measures ultimately helped to avoid a more severe downturn, these were mainly the result of steps Congress took a year earlier despite Truman’s (and the CEA’s) recommendations, including stepped-up defense spending, the Marshall plan, and a $5 billion tax cut, the last of which passed over Truman’s veto (ibid., p. 37; 41). In short, it appears that deliberate deficit spending informed by Keynesian economics and the 1946 Employment Act played no part at all in the 1949 recovery. Nor, according to De Long (1996, p. 47; also Gordon, 1980) had matters changed much by the 1990s. “Looking back at the budget since World War II,” he wrote then, “it is difficult to argue that on balance ‘discretionary’ fiscal policy has played any stabilizing role.”

[2] It may put the extent of the public’s WWII-era saving into perspective to compare it to what it saved during the 2020–21 COVID-19 pandemic, when lockdowns, business closings, and the disease itself had effects similar to those of wartime shortages and rationing. Defining “excess saving” as any savings above 7.5 percent of disposable personal income, Gillian Brunet and Sandile Hlatshwayo (2022, p. 3) determine that the public’s excess savings during the pandemic amounted to 6.8 percent of its disposable income. The corresponding figure for WWII was 16.8 percent.

[3] Despite the fact that wartime credit controls were still in place, total consumer credit began to grow rapidly immediately after V‑J Day. When controls were finally lifted, on November 1st, 1947, credit grew still more rapidly (McHugh 1947). One must bear in mind, however, that this growth was from a record-low wartime level, and that, rapid as it was, incomes also rose rapidly, so that it took until 1952 for consumer credit to once again amounted to roughly the same percentage of personal income it amounted to in 1940.

[4] Thus Keynes, writing in 1936 (1936, p. 545), observed that “The increase in inventories in 1929 was probably for the most part designed to meet demand which did not fully materialize; whilst the small further increase in 1930 represented accumulations of unsold stocks.” The very low level of inventories at the end of 1933, finally, “was an almost certain herald of some measure of recovery.” “In general,” Keynes concluded, “an aggregate of net investment which is based on an increase in business inventories beyond normal is clearly precarious.”

[5] The worst postwar case of a severe downturn marked by a lack of real net private domestic investment was the Great Recession, when such investment briefly turned negative in 2009 (Martin 2016; Higgs 2013). Five years later, it was still only two thirds of its 2007 peak. Yet, poor as this performance was, it pales beside that of net private investment between 1929 and 1946.