About a month ago, a Facebook post drew my attention to an attempt, by Casey Pender of Prague’s CEVRO Institute, to test my thesis that free banking contributes to NGDP stability using statistical evidence from Canada, which had a relatively free banking system between 1867, the year of Canada’s confederation, and 1935, when the Bank of Canada was established.

In “Some Odd Data on Free Banking in Canada,” a blog post discussing his preliminary findings, Pender reports that he had hoped to be able to show that Canada, from 1867–1935, had a more stable NGDP percent change from year to year than the U.S. And I thought this would be an easy and quick historical example that I could use to bolster my underlying theory. But things seem like they just ain’t so.

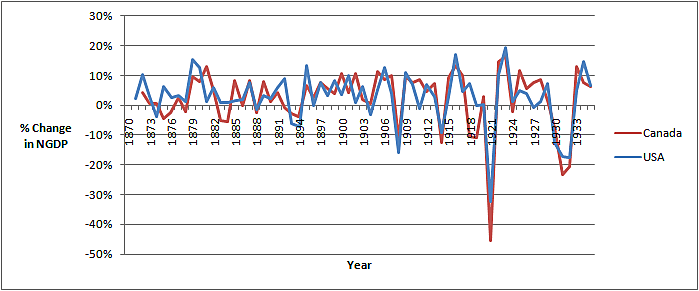

Instead, in comparing the fluctuations of Canadian and U.S. NGDP using data from the Macrohistory database, Pender found that Canadian NGDP was not less but more volatile. Moreover that conclusion held not just for the full 1870–1935 sample period, but also for the sub-period 1870–1914, which omits various extraordinary Canadian government interventions during WWI and the Great Depression.

Here is Pender’s chart showing his results from the full sample period:

Having now been made privy to these findings, I suppose that you are looking forward to seeing ol’ Doc Selgin eat humble pie. Well, you can quit holding your breath ’cause that won’t be happening anytime soon. In fact, for the moment at least, I remain thoroughly impenitent.

How come? First of all, I never claimed that free banking alone could achieve any particular degree of absolute stability of nominal spending. What I have claimed is that, by tending to offset changes in the velocity of money with opposite changes in its quantity, free banking makes for a more stable relationship between the level of overall spending and the available quantity of base or high-powered money than might exist otherwise. To the extent that the available quantity of base money itself changes, however, the quantity of money will also tend to change independently of its velocity. Total spending will then tend to vary also.

What’s more, under an international gold standard regime like the one in place during Canada’s free banking episode, the amount of base money in any particular gold standard country was hardly likely to remain stable or grow at a very steady rate. On the contrary: changes in trade patterns and international capital flows were bound to routinely alter the distribution of gold among gold standard countries, just as changes in trade patterns and capital flows within individual countries are bound to alter the distribution of gold among those countries’ various regions. To the extent that it consisted of holdings of monetary gold, Canada’s monetary base was no less subject to change than the monetary base of, say, Nova Scotia.

In fact during the free-banking era Canada’s base money consisted of both monetary gold and paper “Dominion notes” first issued by the Canadian government in 1866. While some portion of these had to be fully backed by gold, there was also an un-backed or fiduciary component, the quantity of which rose from just $8 million in 1868 to $30 million by the outbreak of World War I. Until 1885 or so at least, those fiduciary issues, instead of being linked even loosely to gold flows, or otherwise regulated for the sake of economic stability, varied according to the Canadian governments’ fiscal needs. Consequently Dominion note issues tended to be an additional cause of irregular changes to Canadian NGDP.

A proper test of the theory that free banking helped to stabilize Canadian NGDP must therefore consider, not just fluctuations in Canadian NDGP as such, but the relationship between those fluctuations and underlying changes in Canada’s monetary base. So long as Canada’s NGDP fluctuations were driven by underlying changes in Canada’s stock of base money, instead of being independent of such changes, the fluctuations were perfectly consistent with the theory.

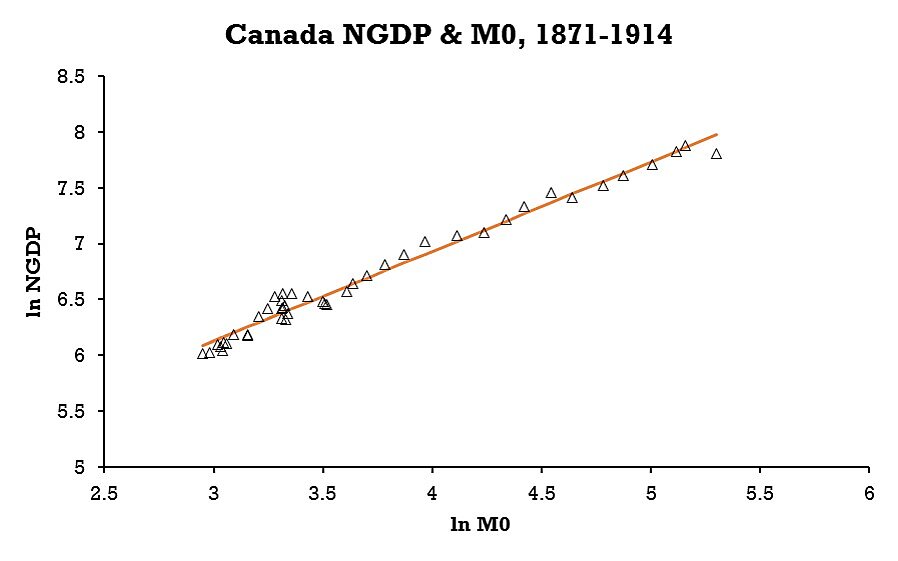

So, what does the record have to say about it? To find out, I had Tyler Whirty, the CMFA’s trusty RA, run some simple regressions for me, with Canadian NGDP as their dependent variable, and Canada’s stock of base money (M0) as the independent variable. The NGDP estimates are the same ones employed by Pender, from the Macrohistory database[1], while the monetary base numbers are from Metcalf, Redish, and Shearer (1998). So far we’ve looked only at the pre-WWI record, as that era is most aptly described as one of relatively unblemished free banking. We also ran the regressions both using raw data and after taking logs. I shall report only the log results, as those fit the data best; but the general conclusions to be reported here don’t depend in the least on the log transformations.

The results, shown in the next figure, are not just consistent but remarkably consistent with the theory, and especially so given that Canada’s arrangement involved some not entirely trivial departures from the theory’s assumptions, one of which is that paper money is supplied by commercial banks alone. (In fact, Canada’s banks were prohibited from issuing notes worth less than $5.) The regression R‑squared is .980254, while the coefficient on M0, about .80, seems quite reasonable allowing for the fact that some Canadian base money, including smaller Dominion notes, circulated instead of serving as bank reserves.

Although the Canadian results seem perfectly consistent with the theory, we still have to compare them with evidence from the U.S. as a step toward establishing that the stable relationship they point to might be attributable to Canada’s having had a free banking system: were a similarly close relationship to exist in the U.S. data, that would suggest that Canada’s distinct institutional arrangements, including free banking, didn’t really make any difference.

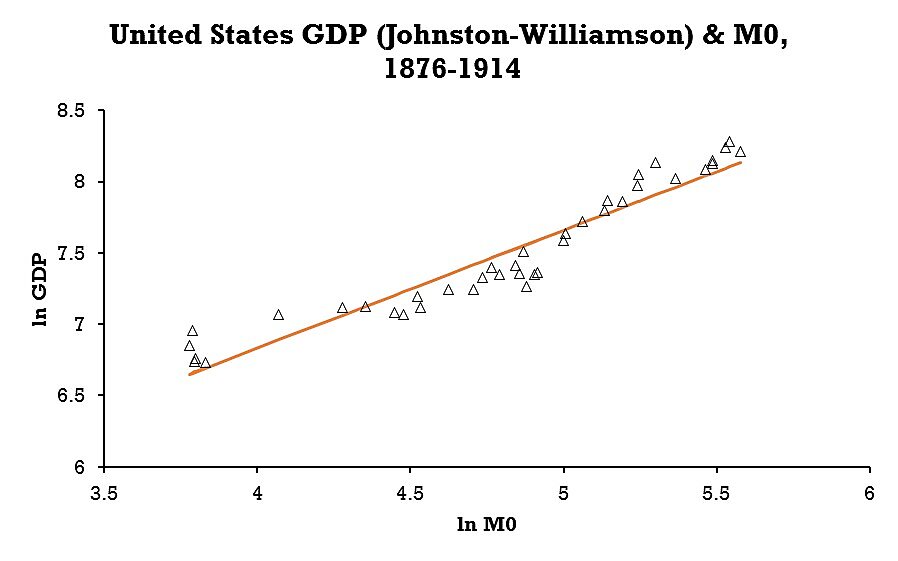

For our base U.S. regression, we drew again upon the Macrohistory database, using its U.S. NGDP estimates (which were originally developed by Louis Johnston and Samuel H. Williamson[2]). For the U.S. monetary base, we subtracted national bank notes from Philip Cagan’s monetary base figures: while Cagan himself justified including those banknotes by noting that they were practically claims against the U.S. Treasury, we exclude them because, despite that, they were neither legal tender nor capable of satisfying banks’ legal reserve requirements.

Because Cagan’s numbers only start in 1875, the U.S. regression covers a somewhat shorter period than the Canadian one.

While the results of the U.S. regression suggest a relationship between U.S. NGDP and M0 that’s broadly similar to the Canadian one (M0 coefficient .825), that relationship, as depicted in the next figure, is considerably less tight, with an R‑squared of .908. That the Canadian relation should be so much tighter now seems all the more remarkable, given both the relatively small size and openness of Canada’s economy, and its heavy dependence upon U.S. exports to the U.S.

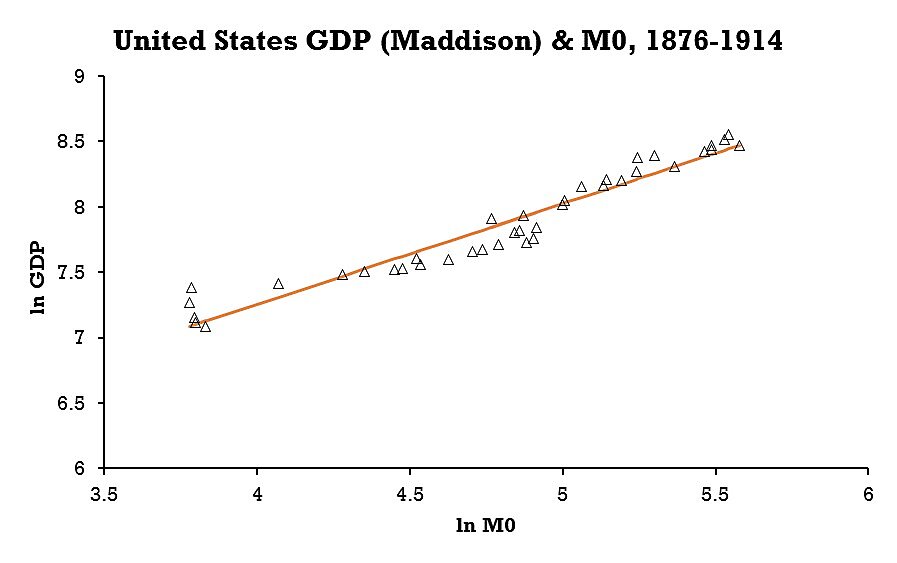

To check the robustness of these U.S. results, we performed the same regression using Angus Maddison’s NGDP estimates in place of the Johnston-Williamson numbers. Although the R‑squared, of about .0935, is a bit higher in that case, the coefficient (.769) is similar:

In brief, both our Canadian regression results themselves, and a comparison of those results with results using U.S. data, seem fully consistent with the theory that free banking helps to stabilize the relationship between NGDP and the monetary base.

Does that mean they confirm the theory? Alas, it doesn’t. Freedom in banking is but one of many differences between the pre-WWI Canadian system and its U.S. counterpart. Furthermore, even if Canada’s more stable NGDP-M0 relationship were in fact due to its having had a relatively free banking system, it wouldn’t follow that my theory is correct. Free banking could well have contributed to the stable relationship in question for reasons apart from the one my theory points to. We know, for example, that branch banking — itself an element of free banking — made Canada’s system less fragile, and therefore less vulnerable to financial crises, than the U.S. system. We also know that financial crises tend to involve a collapse in bank credit and spending. So the relative stability of the Canadian NGDP-M0 relationship, instead of reflecting a tendency for changes in M to offset opposite changes in V, may instead simply have reflected a relative lack of banking crises and associated increases in the ratio of bank reserves to bank credit. Although all this is still good news for fans of free banking, it leaves my particular hypothesis unproven.

In short, while my theory has yet to be discredited, it also has yet to be confirmed. I hope that either Mr. Pender or some other enterprising econometrician will eventually settle the matter, one way or the other.

__________________

[1] Òscar Jordà, Moritz Schularick, and Alan M. Taylor, “Macrofinancial History and the New Business Cycle Facts,” in NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2016, volume 31, edited by Martin Eichenbaum and Jonathan A. Parker. 2017. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[2] Louis Johnston and Samuel H. Williamson, “What Was the U.S. GDP Then?” MeasuringWorth, 2017.