Congress created the H‑2A program in 1986 to allow legal foreign workers to temporarily work for U.S. farmers who were unable to hire qualified Americans. However, illegal immigrant workers came to dominate the industry in the 1990s, and the H‑2A program was rarely used. While it still supplies only about 10 percent of farm labor, H‑2A employment has increased fivefold since 2005.

The H-2A program needs reforms, but productive reform is only possible if policymakers understand how the system currently operates. This brief explains how the H-2A visa program works. Its main findings include the following:

- The H-2A program has more than 200 rules and is bureaucratically complex.

- H-2A minimum wages are higher than every state’s minimum wage by, on average, 57 percent.

- Americans accept only 1 in 20 H-2A job offers, and most later quit.

- H-2A expansion is likely responsible for much of the large decline in illegal immigration from Mexico.

- Violations of H-2A regulations are generally minor. An average of only 0.27 percent of farmers per year have been barred from the program because of serious H-2A violations.

H‑2A Program Rules

The H-2A program is an employer-sponsored temporary worker program, meaning that farmers initiate the process, not the workers. The H-2A visa program has no numerical cap but is restricted to temporary or seasonal jobs lasting less than a year.1 This requirement significantly limits participation and effectively bars dairies and most animal farms that demand labor year-round.2 H-2A’s most widely used predecessor—colloquially known as the Mexican Bracero Program (canceled in 1964)—had no such limitation.3 The H-2A program also narrowly defines “agriculture,” excluding most meat packers and processors.4

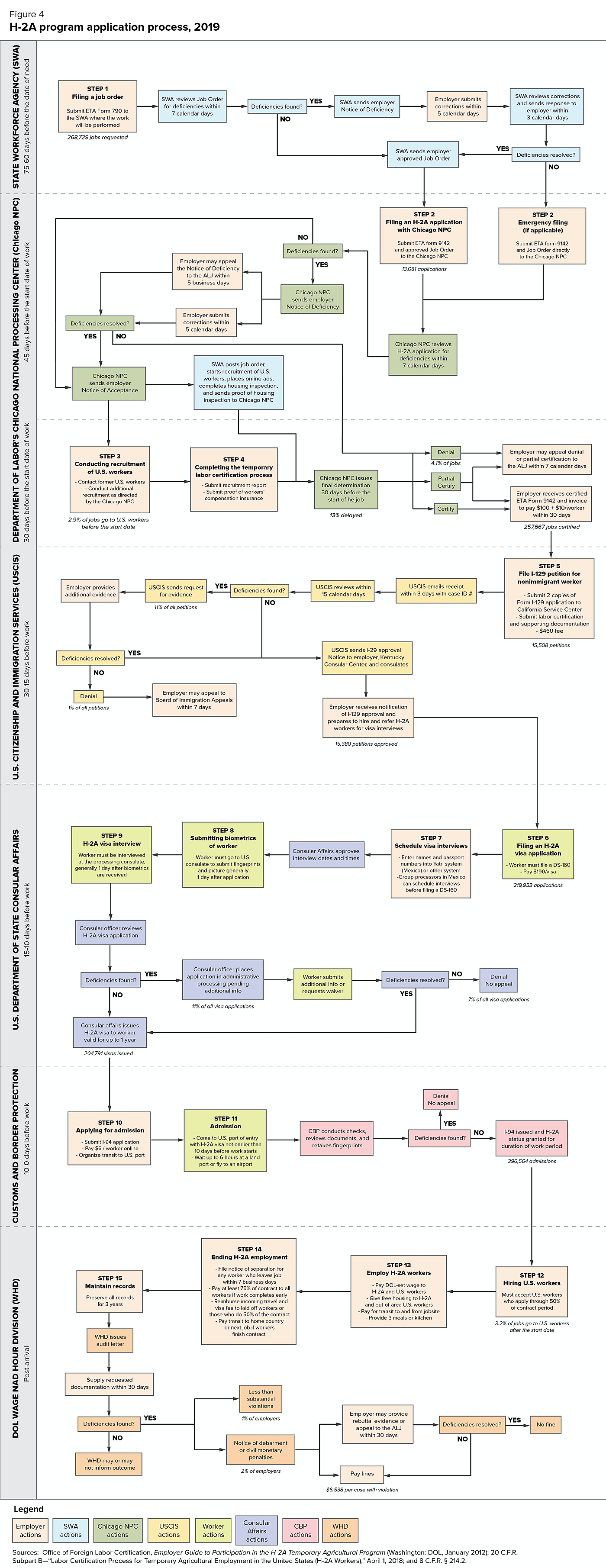

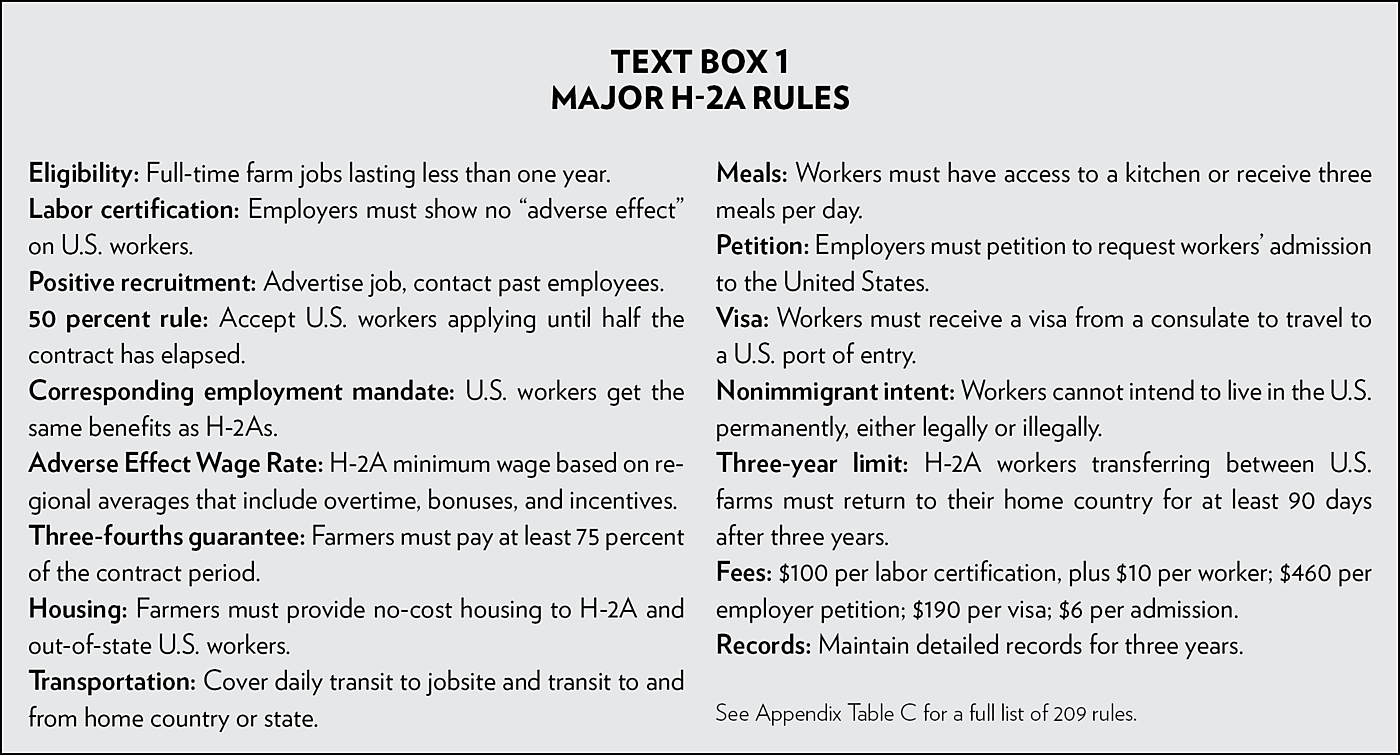

Figure 1 broadly outlines the H-2A process. The Government Accountability Office has found that the “complexity of the H-2A program poses a challenge for some employers” because it “involves multiple agencies and numerous detailed program rules that sometimes conflict with other laws.”5 In 2014, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) ombudsman characterized the H-2A program simply as “highly regulated.”6 Appendix Table C details a noncomprehensive list of 209 H-2A rules that apply to workers and farmers, and Text Box 1 is a short summary of those rules.

To start, when farmers have jobs that they want to fill with H‑2A workers, they must first receive a labor certification from the Department of Labor (DOL).7 They must anticipate a worker shortfall and initiate the labor certification process 60 days before the job’s start date by submitting job orders to State Workforce Agencies (SWAs), which are state-run entities that help unemployed U.S. workers.8 The SWAs guarantee that job offers comply with H‑2A regulations and inform unemployed Americans about the job opportunities.9 Farmers meanwhile must contact former U.S. employees and advertise the jobs.10

If too few U.S. workers apply, DOL will again review the jobs and certify the farmer to hire foreign workers for the remaining positions. The law requires DOL to make certifications at least 30 days before the job starts.11 Delays have cost farmers millions of dollars in lost crops.12 But the internet has improved DOL processing: it deployed online applications in 2012, and by 2019, about 94 percent of applicants used it.13 As a result, the department moved from completing just 63 percent of labor certifications within 30 days in 2011 to completing 97 percent in 2015 (Figure 2).14 In 2019, however, delays reemerged as DOL had the lowest rate of timely approvals (86 percent) of any year since 2013.15

If DOL grants the labor certification, the farmer pays fees of $100 plus $10 per worker, up to $1,000 total.16 Even after H-2A workers start, however, farms must continue to accept U.S. workers until half the job period has expired.17 While farmers continue recruiting U.S. workers, they petition USCIS to admit foreign workers and pay a $460 fee per petition.18 USCIS will conduct yet a third duplicative review (after the State Workforce Agencies and DOL) of the jobs.19 This can also delay workers’ arrivals, and while USCIS has a 15-day deadline, it may surpass the deadline if it requests additional information from the farmer, which it did 11 percent of the time in 2019.20 Farmers may generally request workers from only 84 eligible countries.21 Since 2015, USCIS has removed four countries from the eligibility list: Belize, Ethiopia, Haiti, and the Philippines.22

If USCIS approves a petition, workers may apply for visas. They pay a $190 visa fee, which employers later reimburse if the worker finishes at least half of the contract.23 The Mexican Bracero Program streamlined entries by not requiring visas.24 Until 2016, USCIS also permitted visa-less H-2A entries from several Caribbean countries.25

To receive visas, H-2A workers must demonstrate that they do not intend to live in the United States permanently, either illegally or legally.26 Based on the available evidence, less than 1 percent of the illegal immigrants who overstayed visas were H-2A workers, indicating that they value their legal status.27 Farmers petitioned for legal permanent residence on behalf of only 77 H-2A workers in 2018 because workers cannot receive H-2A status with a permanent residence petition pending; the process is too lengthy and expensive for farmers, and employers cannot request permanent residence for workers in temporary jobs.28 Visas authorize travel to the U.S. border, where Customs and Border Protection (CBP) screens workers, grants them admission, and authorizes their H-2A status for the job’s duration.29 CBP charges an entry fee of $6 per worker, and workers often wait in line several hours to enter the country.30

When workers arrive, farmers must pay wages and benefits at rates set by DOL to both H-2A and U.S. workers in “corresponding employment.”31 This parity requirement—which the Bracero Program lacked—applies even if U.S. workers are the vast majority of employees, which discourages new farmers from joining.32 Farmers must usually pay a minimum wage called the Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR), which is the costliest and most contested rule.33

The AEWR is a regional average wage based on annual government surveys.34 The AEWR ignores differences between localities, detailed job types, skills, and experience. Both the H-2B nonagricultural and H-1B skilled worker programs determine wages for local areas for specific occupations and permit some private surveys.35 The H-1B program also provides four skill levels.36 The 2020 hourly AEWR (Figure 3) was between $11.71 (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina) and $15.83 (Oregon and Washington).37 The 2020 AEWR was higher than every state’s minimum wage by an average of 57 percent.38

DOL adjusts the AEWR annually based on a survey and uniquely classifies overtime, hazard pay, bonuses, performance incentives, and all other payments as wages.39 This inflates the base hourly rate before adding these types of extra compensation for the following year.40 This inflated average rate then applies to all workers, pricing out H-2A and U.S. workers who had below-average wages. When these workers drop out, the surveyed wage is artificially inflated even further. Many farmers feel these procedures put the AEWR on an upward escalator that becomes more disconnected from reality each year. The average AEWR has grown about twice the rate of inflation since 2001.41 In some states, the AEWR increased 23 percent in 2019.42

Farmers must guarantee AEWR wages equal to at least 75 percent of the projected job period even if it finishes early.43 H-2A farmers must also finance transit to and from jobsites and offer workers either kitchens or three daily meals.44 H-2A workers and out-of-the-area U.S. workers must receive housing at no cost. Excluding the AEWR, housing is the costliest rule for farmers: it accounts for nearly a quarter of H-2A requirements (see Appendix Table C) and inflates total compensation far above the non–H-2A rate.45 In comparison, the H-2B program for nonagricultural jobs generally has no housing mandate.46

When H-2A workers complete 50 percent of the job, farmers must reimburse their expenses for travel to the United States and, if workers complete the job, pay for the trip back to their home country, unless workers find other H-2A jobs.47 Regulations require H-2A workers to find another employer within 30 days and mandate absences of at least three continuous months every three years.48 DOL’s Wage and Hour Division conducts audits of H-2A farmers and fines those who fail to comply with regulations.49 Figure 4 illustrates a simplified version of H-2A filing procedures.

Given the high costs and regulatory complexities of the H-2A program, farmers use it as a last resort. For this reason, it served few farms until around 2005 but has grown rapidly since then (Figure 5). In 2019, DOL certified about five times as many jobs for H-2A employment as in 2005—an increase from 48,336 to 257,667.50 These certified jobs led to 204,366 visas for new foreign workers to travel from abroad, and H-2A workers were admitted to the United States about 397,000 times.51 Nonetheless, H-2A jobs were just 10 percent of the roughly 1.4 million full-time equivalent agricultural jobs in 2019.52

U.S. Workers and the H‑2A Program

The first sections of Figure 4 cover DOL’s labor certification.53 The Government Accountability Office has called this process a “time consuming, complex, and challenging” exercise that “imposes a burden on H-2A employers that is not borne by employers who break the law and hire undocumented workers.”54 The labor certification is intended to demonstrate that H-2A workers will not “adversely affect” U.S. workers.55 Numerous government and academic reports have found that this expensive effort is largely futile, producing few, if any, hires that would not otherwise occur.56

DOL has continuously raised H-2A minimum wages to induce U.S. workers to apply, but Department of Agriculture economists have concluded that “farm labor supply in the United States is not very responsive to wage changes.”57 When Congress canceled the Bracero Program—which had admitted at its peak nearly a half a million Mexican workers—farmers in areas that lost braceros hired no more U.S. workers nor did they raise wages compared to other farms.58 Instead, they mechanized, shifted to less labor-intensive crops, and downsized.

With more hospitable and consistent jobs available elsewhere, U.S. workers pass on seasonal farm jobs. For example, the North Carolina Growers Association sought to fill 7,008 jobs through the H-2A program in 2012 and just 143 U.S. workers—2 percent of those demanded—applied for and showed up for the jobs, and only 10 completed the growing season. From 2007 to 2010, only about 50 out of the 290,000 net increase in unemployed North Carolinians chose agricultural jobs (Figure 6).59

DOL found that from 2014 to 2016, 87 percent of H-2A employers requesting U.S. workers received none.60 Just 6 percent of H-2A jobs ultimately went to U.S. workers, and a majority of those showed up after the harvest began and H-2A workers had started.61 This means that H-2A recruitment—including higher wages and state and federal oversight—provided farmers with U.S. workers in time for harvests just 2.9 percent of the time. Even then—as the North Carolina growers found—many U.S. workers “either did not report to work or voluntarily resigned.”62

Of course, even the few U.S. workers in H-2A jobs would likely have found jobs without the extensive regulatory structure. The H-2A employment surge has even coincided with a dramatic drop in unemployment for domestic farmworkers (Figure 7).63 In other words, farms have hired domestic workers alongside H-2A workers.

Farmers and the H‑2A Program

American farms produced about $133 billion—a bit below 1 percent—of the U.S. gross domestic product in 2017. Related downstream industries that depend on U.S. agricultural production contributed more than $1 trillion to GDP.64 This important industry spends about $40 billion on hired help and depends on reliable sources of workers because harvests must occur during brief time windows.65

Farmers hire foreign workers because very few U.S. workers want farm jobs despite rising wages. The illegal immigrant share of domestic farmworkers grew from 7 percent to 56 percent from 1989 to 2000, but dropped to 48 percent by 2016 (Figure 8). Since 1989, the share of U.S.-born farmworkers fell from about 40 percent to roughly 25 percent (Figure 8).66

In addition to faster H‑2A processing times (Figure 2), farm labor markets have changed since the late 1990s to encourage hiring more H‑2A workers. Most important, the share of domestic farmworkers who are new (non–H‑2A) entrants to U.S. farm work began cratering, falling from 27 to 4 percent from 1997 to 2016.67 With fewer workers coming down the road, more farmers sought new workers through the H‑2A program.

Fewer new entrants partly explains why labor demand has outstripped the supply of H‑2A workers, causing farm wages to rise (Figure 9).68 Farm laborers in crop production—the primary H‑2A activity—saw especially outsized wage growth. In 2001, such laborers made 53 percent as much as all workers weekly, compared to 60 percent in 2019.69

Farms where labor expenses are the highest hire the most H‑2A workers. Fruits, vegetables, horticulture, and tobacco farming constituted nearly three-quarters of H‑2A jobs in 2018, and these industries spend double or triple the share on labor as other agricultural industries (Table 1).70 While dairies and other animal farms use the H‑2A program less, they also face a major legal obstacle to participating because most of their jobs are permanent rather than, as H‑2A law requires, temporary.71

The H-2A increase has likely lowered illegal border crossings, reducing the supply of illegal farmworkers and prompting still more farmers to hire H-2A workers. From 2000 to 2018, a 1 percent increase in H-2 visas for Mexicans—including some under the H-2B program for nonagricultural jobs—was associated with a 1 percent decline in the absolute number of Mexicans apprehended for crossing illegally.72 Figure 10 shows that when H-2A admissions are high, Border Patrol apprehensions (per agent) have remained low.73 As one H-2A worker told the Washington Post in April 2019, “Most of my friends go with visas or they don’t go at all.”74

Foreign Workers and the H‑2A Program

Almost all H‑2A workers are Mexicans. Figure 11 shows the number of H‑2A visas issued by nationality from 1997 to 2019.75 Mexicans dominate the flow every year, and from 2005 to 2019, the Mexican share further increased from 82 to 91 percent. The next most common nationality is South African (2 percent), followed by Jamaican (2 percent), and Guatemalan (1 percent). All other nationalities amounted to just over 3 percent.

Farmers must petition the government to request foreign workers before workers can receive visas, meaning that farmers control which countries the workers come from. As H‑2A employer requests grew, U.S. recruiters expanded their existing recruitment in Mexico.76 For this reason among others, it is unlikely that farmers will hire many non-Mexican workers in the foreseeable future.77 If Congress wants to encourage the hiring of other nationalities that are prone to making illegal border crossings, it needs to expand the program, such as allowing year-round industries to use H‑2A visas but only to hire from those specific countries—thus forcing employers to recruit there.78

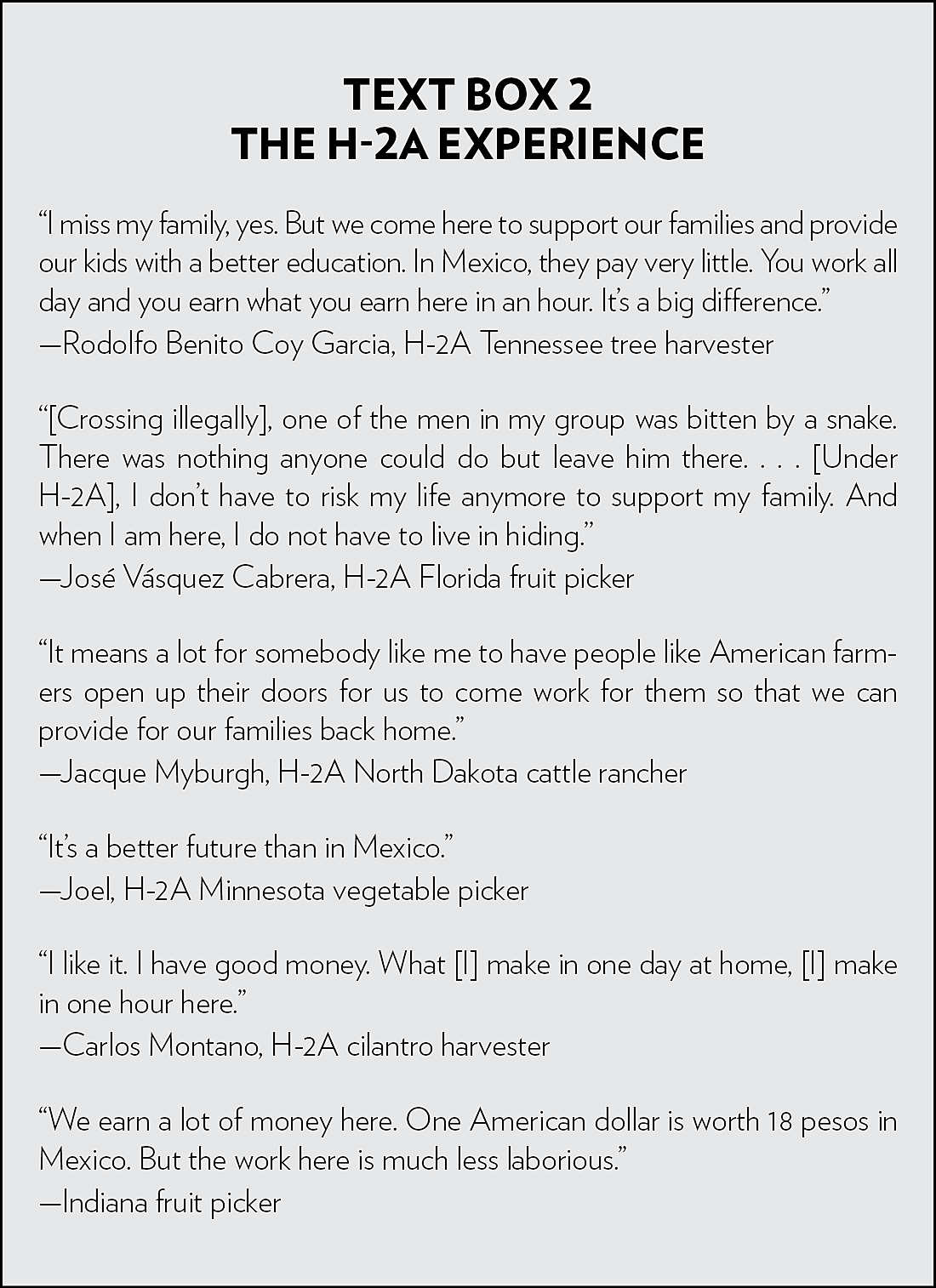

Higher U.S. wages motivate Mexicans to accept U.S. farm jobs (see Text box 2).79 The annualized wage for H‑2A workers was almost $25,000 in 2019.80 Mexico’s minimum wage for farmworkers was just $4.64 per day, less than $1,200 per year.81 Even the highest paid agricultural workers in Mexico only earn $15 per day.82 Even if H‑2A minimum wages fell, Mexicans would still greatly benefit from H‑2A jobs.83 Indeed, a larger number would benefit because a lower wage would allow farmers to hire more workers.

Nearly all H-2A workers willingly attempt to return year after year. While the State Department fails to disclose the frequency at which H-2A workers return, one indication is that the similar H-2B program for nonagricultural workers—most of whom are also Mexicans—doubled in size when Congress allowed H-2B returning workers to be exempt from the cap in 2007.84 The H-2A program is uncapped, so no similar experiment can occur, but H-2A workers also report repeatedly participating.85

The frequency of returning workers indicates that whatever the downsides, foreign workers prefer H-2A jobs to jobs in their home countries or illegal status. Unfortunately, abuses can happen. Polaris, a group dedicated to combating human trafficking, received 327 complaints to its human trafficking hotline from H-2A visa holders from 2015 to 2017—about 0.08 percent of visas issued.86 These are tragic cases, but as David Medina of Polaris told the Guardian, most H-2A workers’ “biggest fear is to lose that visa.”87

The Wage and Hour Division of DOL investigates abuses and enforces H-2A rules. Figure 12 compares the number of H-2A wage and hour violators fined by the division to the number of unique H-2A employers each year since 2008.88 Even with H-2A’s immense regulatory complexity, DOL fined just 2 percent of H-2A employers, on average, annually from 2008 to 2018. Most fines were for minor infractions, worth on average just $237.89 The maximum available fine per violation in 2019 was $115,624.90 Fewer than 20 employers from 2008 to 2018 had serious enough violations to have been suspended or debarred from the program—an annual rate of 0.27 percent of the employers.

While farmers, unions, and migrant advocates disagree over the necessity of more intrusive auditing of all employers to deal with such limited abuses, they generally agree that H‑2A workers should be better able protect their own rights by leaving to find new jobs.91 This would require lengthening the period that workers have to find another job and allowing existing H‑2A workers to be recruited on the same terms as U.S. workers so that subsequent employers need not have already initiated the complex recruitment process before the worker applies. These changes would be a rare win-win reform for both farmers and foreign workers.

Conclusion

The H‑2A program has more than 200 complex rules that reduce farmer participation. Farmworker wages have increased continuously since 2001, but H‑2A recruitment of American workers still attracts less than 3 percent of the needed workers by the job’s start date. Higher wages, low unemployment rates, and fewer U.S. workers entering agriculture have encouraged more farmers to use the program, which has likely resulted in fewer illegal border crossings. H‑2A abuses of foreign workers are rare, and H‑2A workers choose to return year after year because program conditions improve their lives. Congress could expand on this successful program by making H‑2A visas available to year-round industries and streamlining its rules and regulations.

Appendix

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.