This study examines the growing phenomenon of debanking—the sudden and often unexplained closure of individuals’ or organizations’ financial accounts. While media and political narratives often attribute these closures to political or religious discrimination, this study finds that the majority of debanking cases stem from governmental pressure. To identify this cause more accurately, the study distinguishes between four forms of debanking—governmental, operational, political, and religious—evaluating each form in turn. Based on public evidence, governmental debanking appears to be the most significant issue. Congress can correct this issue by reforming the Bank Secrecy Act, repealing confidentiality laws, and permanently ending reputational risk regulation. Doing so would reduce the incentives to debank, expose how widespread debanking has become, and cut out the tools that the government has used to pressure banks and other financial institutions.

Introduction

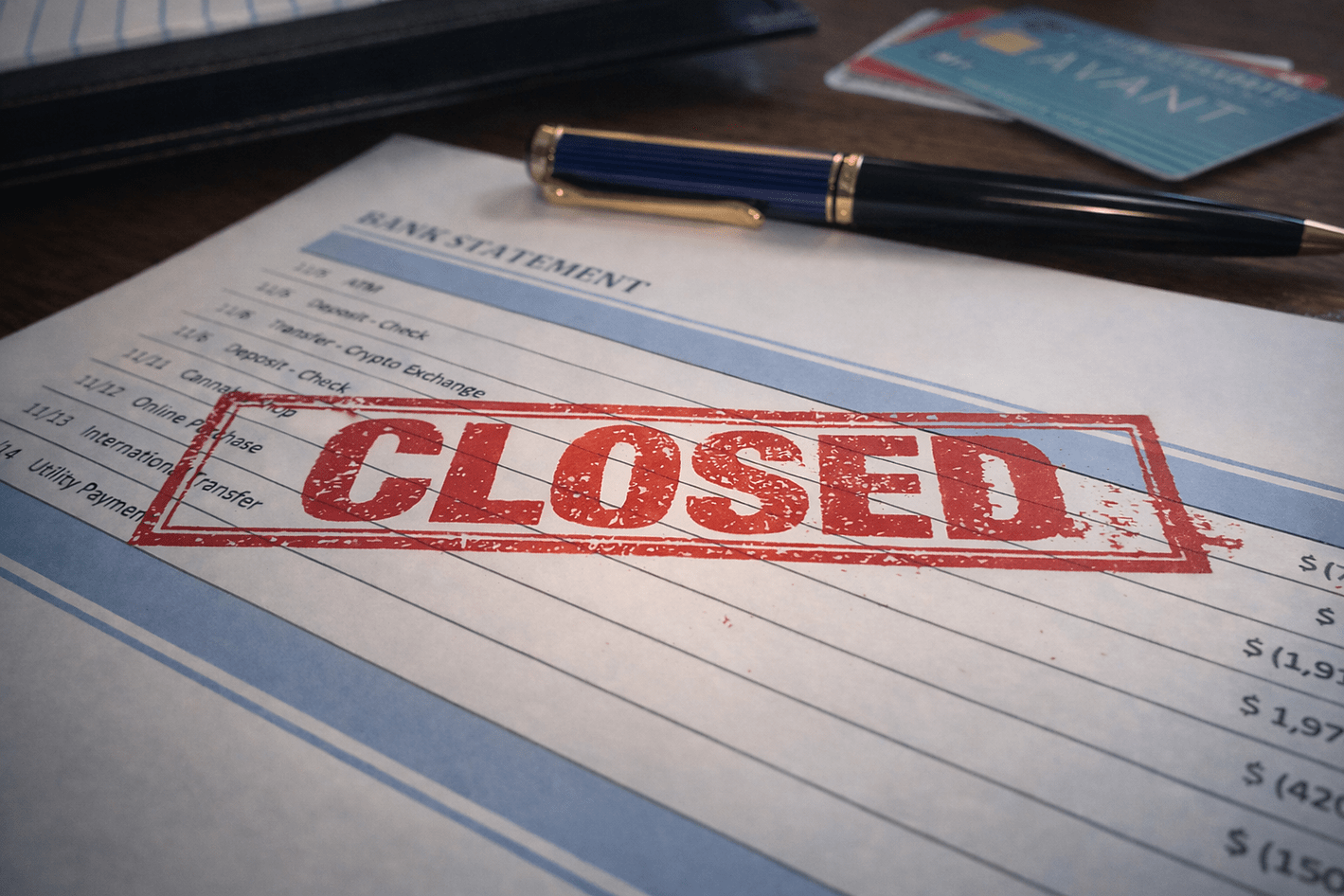

Debanking can be a frustrating and nerve-racking experience. A sudden notice from the bank announces that you have 30 days to collect your money and find another bank. You panic. What could you have done wrong? You paid your bills on time (or at least most of the time). What could have caused this change? You call to ask the bank, and you’re told there’s nothing more that can be said. You’re left in the dark.

On the other side of the line, however, bankers are often stuck between a rock and a hard place because they are bound by confidentiality. In some cases, it’s possible that even customer service representatives are not allowed to know what took place to justify the account closure. Bankers generally recognize these requirements as part of anti–money laundering, know your customer, and countering the financing of terrorism regulations (often abbreviated as AML, KYC, and CFT regulations). Yet, the public is rarely aware of these requirements.1 This divide has created frustration on both sides.

If Congress wants to bring relief and reduce the debanking phenomenon, it’s time to eliminate the confidentiality that has shrouded the system. It’s time to take the practice of reputational risk regulation off the table. And it’s time to reform the Bank Secrecy Act regime that has deputized financial institutions as law enforcement investigators.

Debanking Explained

In the most basic sense, debanking is simply the sudden closure of a financial account. This experience is usually associated with banks, but it can happen with other financial institutions as well (e.g., credit unions, exchanges, payment apps, etc.). With that said, there are also several subcategories of debanking to consider. The most infamous case of debanking—Operation Choke Point—can be described as governmental debanking. The contrast to that is operational debanking.2 In addition, some groups have recently claimed the existence of both political and religious debanking.3

To better understand the dynamics at play, it helps to look at how these different forms of debanking have taken shape—and how easily they can be conflated.

Governmental Debanking

Governmental debanking is what occurs when the government pressures a financial institution to close a customer’s account.4 Governmental debanking can occur in two forms. The first form occurs when the government directly instructs a financial institution to close an account. This instruction can be as casual as a letter or as formal as a court order. The second form, however, is more indirect. It involves the use of laws and regulations to make it increasingly more difficult to serve customers.

Let’s consider a few examples.

The case of National Rifle Association (NRA) v. Vullo made headlines in 2018 after Maria T. Vullo, superintendent of the New York State Department of Financial Services, issued regulatory guidance instructing financial institutions to review relationships with the NRA and “take prompt actions” to manage the risk of being associated with the organization.5 Vullo joined with then–New York Governor Andrew Cuomo to say that the government “urges all insurance companies and banks … to join the companies that have already discontinued their arrangements with the NRA.”6 This example is a case of direct governmental debanking.

In another example, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (often abbreviated as FDIC) sent private letters to instruct financial institutions to stop conducting cryptocurrency-related activity.7 Some people may take comfort in the fact that the agency only told these institutions to “pause all crypto asset-related activity.” Financial institutions, however, know all too well that the government’s suggestions are rarely optional.8 Furthermore, the agency failed to provide a timeline or follow up with those financial institutions.9 So, in practice, these letters were effectively termination orders. Again, this example is a case of direct governmental debanking.

Finally, yet another example occurred when companies sending money between the United States and Somalia quickly found themselves debanked in 2015 after “a broad US crackdown on money laundering.”10 At the time, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency ordered a bank to shut down these accounts unless the bank could “maintain sufficient transparency to reasonably ensure the legitimacy of the sources and uses of customer funds.” Unfortunately for the companies, the cost-benefit analysis of tracking funds and increasing supervision was not in their favor, and their accounts were closed—marking another case of direct governmental debanking.

Examples of governmental debanking are not always so direct. Sometimes they take on a more indirect form. Rather than explicitly order the closure of specific accounts, the government makes it economically infeasible to serve customers by increasing regulatory costs.

One example of indirect governmental debanking occurs when financial institutions close accounts after a customer incurs too many suspicious activity reports (often abbreviated as SARs). These reports were established under the Bank Secrecy Act regime such that financial institutions must report customers when they do something out of the norm.11 While criminal activity should not go unchecked, these reports rarely catch actual wrongdoers. For example, one of the most common reasons for filing a suspicious activity report is that a customer made a transaction close to $10,000, as doing so could be considered a purposeful attempt to avoid the threshold for filing a currency transaction report (often abbreviated as CTR).12 Yet, each report still counts against a customer because financial institutions can face hundreds of millions of dollars in fines if it turns out that someone was indeed breaking the law and the accounts were not closed.13 In effect, the incentives push financial institutions to be more sensitive than they might otherwise be.

Another example of indirect governmental debanking occurs when banks have left high-risk areas. In one report, the Government Accountability Office found that the rules under the Bank Secrecy Act required banks working near the southwest border to conduct “more intensive account monitoring and investigation of suspicious activity.”14 Eventually, the compliance costs (and the risks) became high enough that these banks closed their branches in the area and shut down accounts. More recently, the Trump administration tried to increase financial surveillance at the border so severely that affected businesses would likely have had to shut down under the new regulatory costs had the order not been stopped by the courts.15

Finally, Operation Choke Point was an example of both direct and indirect governmental debanking. Originally led by the Department of Justice, the operation began with the intent of targeting fraudulent businesses but was quickly used to target payday lenders, pawn shops, gun shops, state-licensed cannabis dispensaries, and other businesses.16

One of the key tools in Operation Choke Point was the regulation of reputational risk.17 As the name suggests, this practice involves shifting the focus of regulators away from traditional factors found on a financial institution’s balance sheet and toward broader issues such as negative publicity.18 When it came to the question of who might present a higher risk to the financial institution’s reputation, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation at one point named 30 different categories of businesses.19 Despite this list describing mostly legal businesses, the message was clear: Doing business here meant facing higher scrutiny, higher compliance costs, and a higher chance of enforcement actions.

Taken together, these examples show that governmental debanking occurs when the government orders or otherwise effectively forces financial institutions to close accounts.

Operational Debanking

Operational debanking is what occurs when a financial institution chooses to close the account of a customer because it is no longer in the institution’s interest. It could be because the customer violated part of their contract with the institution or because the institution itself decided to move in another direction.

Let’s consider a few examples.

Bank of America made headlines in 2018 when it announced that it was stepping away from certain gun manufacturers.20 According to reporting at the time, this decision was made after discussions with employees and customers who had been affected by high-profile shootings.21 Notably, however, gun manufacturers were not cut off from the entire financial system.22 Bank of America only closed some accounts, while it maintained accounts with other gun manufacturers (e.g., Remington and Vista Outdoor). Furthermore, the affected manufacturers could still open accounts elsewhere. So while it seems that Bank of America saw the bad press as unprofitable, others saw it as an opportunity—marking this example as a case of operational debanking.

A similar case occurred in 2019 when JPMorgan Chase announced it would no longer finance privately owned prisons and detention centers.23 Again, this decision appears to have been primarily a response to customers and other members of the public who had protested at shareholder meetings and even in front of JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon’s apartment.24 And again, the privately owned prisons were not cut off all at once or from the entire financial system. Instead, JPMorgan Chase reduced its credit exposure over time.25

With that said, most cases of operational debanking are unlikely to make headlines. A less controversial (though likely more common) example occurs when a financial institution closes an account after repeated overdrafts, late payments, or failure to maintain the account. Put simply, the account holder didn’t pay for the service, so the institution stopped offering it. Although banking has become more accessible in recent years as banks have introduced services like overdraft forgiveness and entry-level accounts, there are still times when the cost of offering a service exceeds the benefit. Banks should be free to assess those cases and make the decision whether to close an account.

Taken together, these examples show that operational debanking occurs when financial institutions choose to close accounts as part of their own internal decisionmaking.

Political Debanking

Political debanking is the idea that financial institutions close accounts solely because they are discriminating against a customer’s political party or identity. Although many things can be described as political in nature and cross over into other forms of debanking, the core requirement for “political debanking” as defined here is that a customer was explicitly targeted for their political beliefs. In practice, cases of political debanking have almost exclusively involved claims that conservatives are being targeted.26 However, many of these cases actually appear to be examples of governmental debanking.

Let’s consider a few examples.

The most well-known claim of political debanking occurred shortly after protestors entered the US Capitol on January 6, 2021. More than 300 accounts associated with the Trump Organization were reportedly closed.27 Although Eric Trump has said this experience “was a clear attack on free speech” and “those who dare to express their political views,” these closures coincided with a period in which then–former President Donald Trump and his associates were facing civil and criminal investigations.28 With this context in mind, it seems much more likely that the closures were really a case of governmental debanking because financial institutions did not want to be caught on the wrong side of the law.

A second, and closely related, example occurred when January 6 protestors were debanked. One study described the closing of these accounts as examples of the “growing weaponization of the financial system to target groups and individuals that engage in disfavored political speech.”29 However, again, the context cannot be ignored. These individuals were at the center of one of the most high-profile legal controversies in recent history. According to one lawyer for the defendants, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and Justice Department were “prodding financial institutions to treat [January 6 protestors] like domestic terrorists.”30 In this case, it again seems more likely that the closures were cases of governmental debanking.

Finally, another example occurred when conservative political commentator Michael Knowles took to social media to reveal he was having issues receiving payments.31 Knowles shared how he received a vague message that there was a problem with his account and that customer support had him going in circles. Facing frustration, Knowles wrote, “I can only conclude that they’ve now decided that certain conservative opinions amount to ‘illegal’ activity.”32 Yet, it seems that what really happened was not political debanking. One day later, Knowles shared that the real reason his account was closed was “a government administrative error.”33 Again, it seems this instance was likely a case of governmental debanking.

Other cases do exist, but there is not enough public information to reliably assess what may have taken place.34 With that said, these examples show that political debanking may be a misdiagnosis. While it’s possible that political discrimination exists, much more evidence is needed to ascribe it as the motive for widespread debanking.

Religious Debanking

Religious debanking is the idea that financial institutions close accounts solely because they are discriminating against a customer’s religion. In practice, cases of religious debanking have largely centered around claims that Christians have been targeted and discriminated against by financial institutions.35 However, looking beyond these claims, publicly documented cases have been few and far between.36 And even then, it seems that these cases may actually be examples of governmental debanking or even operational debanking.

One such case occurred in 2023 when a group of accounts associated with a nonprofit—Indigenous Advance Ministries—working to spread Christianity in Uganda was closed.37 In response, Jeremy Tedesco, senior counsel and senior vice president for corporate engagement at the Alliance Defending Freedom, said, “No American should have to worry that a financial institution will deny them service based on their religious beliefs, but Bank of America appears to have done just that with Indigenous Advance.”38 While such an occurrence would be troubling, it later came to light that one of the accounts was being used for a debt-collection agency in Uganda and that this information had not been disclosed to the bank.39 Operating a high-risk business in a high-risk jurisdiction would likely have posed significant compliance costs. Therefore, it’s unlikely that the issue was with the organization’s Christian beliefs. Given that these costs are incurred under the Bank Secrecy Act regime, it’s likely that this example leans toward being a case of governmental debanking. However, it’s also possible that elements of operational debanking were present, given that the failure to disclose the business could have jeopardized the business relationship.40

Another example occurred in 2022 when the National Committee for Religious Freedom had its accounts closed.41 While headlines said, “Big Banks Discriminate Against Christian Ministries, Churches,” it seemed the real source of the issue was unknown.42 “We can’t really ascribe a motive to this,” said the National Committee for Religious Freedom in one interview. “We don’t know. But if it is religion, that should be frowned upon.”43 However, here too, something strange happened. Additional reporting revealed that the bank was willing to keep the accounts open so long as the organization answered questions related to its 501(c)4 tax status.44 Yet, the organization refused. Considering the accounts could have been reopened, this case walks a fine line in terms of being labeled debanking. However, it appears to lean toward a case of governmental debanking since the problems stemmed from an issue of oversight—something banks cannot legally choose to ignore.

While Christian organizations do not appear to have faced widespread issues, reports have shown that Muslim people are more than twice as likely as the general public to face issues with financial institutions.45 However, again, it’s not clear that the issue is one of faith. What may be more likely is an issue of geography.46 One survey found that the problems for Muslim customers disproportionately stemmed from issues with international transactions, sending money, and keyword flagging. Sending money to family and friends should be an easy endeavor, especially in the digital era. However, having friends and family in high-risk jurisdictions can quickly run afoul under the Bank Secrecy Act regime. In that case, the issue is more so governmental debanking than religious debanking.

Taken together, these examples show that religious debanking may also be a misdiagnosis.

Different Forms Do Overlap

While these labels are helpful, it is important to be mindful that there is some overlap between the different forms of debanking. For example, navigating the regulatory costs incurred under the Bank Secrecy Act is part of a business’s strategic decisionmaking. Still, because those costs stem directly from government intervention, cases of debanking due to Bank Secrecy Act compliance concerns are therefore governmental in nature. Similarly, cases of fraud cover both forms of debanking. While suspicious activity reports are filed for cases of suspected fraud, financial institutions would likely cut ties with customers who lie about their details even without the legal requirement. Another grey area occurs when some organizations are both political and religious in nature. Finally, there is a fine line to draw when assessing operational and political debanking. It would be an operational response to accept the calls of protesting customers to debank a disfavored group, but such a response would veer into political debanking if the protestors were calling for the institution to close accounts solely based on political affiliations. Disentangling the driving motivation for debanking in such cases is not always easy. Therefore, whenever assessing different forms of debanking, care should be taken to recognize the nuances of each situation.

What to Make of Debanking

Based on the available evidence, Congress should prioritize responding to governmental debanking. There are three key reasons for this strategy.

First, governmental debanking is the most pressing issue. The majority of cases over time can be found where government officials have intervened in the market by either directly or indirectly telling banks how to run their business. And the public recognizes it. Although legislation introduced by Republican members of Congress has centered on restricting the conduct of private businesses, 72 percent of conservative citizens saw government intervention as the main issue here.47 Furthermore, governmental debanking is where Congress has the most control and the best ability to fix the issue.

Second, political and religious debanking appear to be almost nonexistent. Out of 8,361 account closure complaints reviewed by Reuters, only 35 complaints mentioned the words “politics,” “religion,” “conservative,” or “Christian.”48 And even where they may exist, the cases appear to be far more complicated than headlines suggest.49 The example of Indigenous Advance Ministries is an illustrative case study of this phenomenon. Although claims of religious discrimination were used to justify pushing state policymakers to restrict access to the financial system, the root issue appears to be that the sole organization cited as an example had not disclosed to the bank that it set up a debt-collection agency in Uganda.50 Congress should resist intervening until, at the very least, more evidence can be collected.

Third, Congress may still be tempted to intervene in operational debanking, but private businesses should be free to make their own decisions, even if it means they face negative consequences from customers. When surveyed, 74 percent of conservatives said banks should be free to make their own decisions because regulatory interventions requiring otherwise could lead to unintended consequences.51 The misguided approach in the Fair Access to Banking Act is an illustrative example.52 In the worst case, the bill responds to government pressure on financial institutions by further restricting what those institutions are allowed to do.

By focusing efforts on governmental debanking, Congress can defend Americans’ economic freedom, avoid creating new distortions, and act where it has both the authority and the responsibility to make meaningful change. For the individuals suddenly locked out of their accounts, the distinction between governmental and operational debanking can make all the difference. Congress should focus reforms where it can truly restore fairness and transparency.

Recommendations

Congress should take a targeted approach to address the problem of debanking—one that both exposes how widespread debanking has become and removes the tools that the government has used to pressure banks and other financial institutions. Both Congress and state policymakers should resist calls to turn banks into utility services by mandating access to accounts. Likewise, policymakers should resist calls to permit account closures only when the risks can be quantified. A notable example of these mistakes can be seen at the state level in Tennessee where a 2024 law made it illegal to deny services based on factors that cannot be quantified.53 Instead, Congress should establish transparency, end reputational risk regulation, and remove the incentives to debank that have been created under the Bank Secrecy Act.

Establishing Transparency

To expose how widespread debanking has become, Congress should repeal the confidentiality requirements that prevent financial institutions from telling customers why their accounts were closed. Time after time, customers have reported feeling helpless because banks say they are not allowed to reveal why accounts were closed.54 For example, after one customer learned that his account was closed due to “unexpected activity,” the bank refused to say more about the exact cause for termination other than that “financial institutions have an obligation to know our customers and monitor transactions.”55

Such confidentiality requirements are particularly relevant in the case of suspicious activity reports. Under current law, it is illegal under 31 U.S.C. Section 5318(g)(2) for a bank to share a suspicious activity report with the customer. In fact, it’s even illegal to confirm the existence of such a report. When these reports are the reason for an account closure, the bank should have the freedom to share that information with the customer.

To be clear, so long as banks are still required to file suspicious activity reports under the Bank Secrecy Act and are at risk of being held at fault if they miss a report, “all their incentives are towards closing accounts.”56 The difference, however, is that customers will actually be allowed to know the root cause of the issue.

While members of Congress may be tempted to go further and force financial institutions to explain their actions, this path is unnecessary. If a financial institution chooses to leave customers in the dark even after these reforms, it potentially will be at their own peril as they become known for being unreliable. Congress should therefore remove this veil of confidentiality and leave the rest to the market. To achieve this end, Congress should repeal 31 U.S.C. Section 5318(g)(2), 12 U.S.C. Section 3420(b), and 18 U.S.C. Section 1510.

Another important issue involves “confidential supervisory information,” as these materials can be used to pressure financial institutions to change their conduct and relationships with customers. Yet, it is illegal to share this information under current law. Congress got it right when it crafted 18 U.S.C. Section 1906 and prohibited regulators from sharing supervisory materials. Things started to go wrong, however, when the Federal Reserve “asserted a legal theory” that these materials belong to the government “even when [they are] produced by the banks and even when the banks themselves are eager to disclose [them].”57 That is backward. Banks should have the ultimate say over how this information is shared.

Congress should instruct the Federal Reserve to reform 12 C.F.R. Part 261 and instruct the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation to reform 12 C.F.R. Part 309 so financial institutions that are the subject of confidential supervisory information may share that information as they see fit.58 Doing so would go a long way in adding transparency that would help better identify whether additional reforms are needed.

Ending Reputational Risk Regulation

Great strides have been made to take reputational risk regulation off the books. Regulators have announced that they will cease the practice, Congress has introduced legislation to prohibit the practice, and President Donald Trump has issued an executive order calling for an end to the practice.59 Still, more is needed to ensure that this cycle does not repeat again. The best way to do so is for Congress to enact legislation that limits the actions of regulators by law.

To take this tool off the table for good, Congress should use the following language:

(1) IN GENERAL.—If a government official formally or informally requests or orders a financial institution to terminate a specific customer account or a group of customer accounts, the government official shall—

(A) provide such request or order to the financial institution in writing; and

(B) accompany such request or order with a written justification for why such termination is needed, including any specific laws or regulations the government official believes are being violated by the customer or group of customers, if any.

(2) JUSTIFICATION REQUIREMENT.—A justification described under paragraph (1)(B) may not be based on the reputational risk to the financial institution.

(3) ELIMINATION OF REPUTATIONAL RISK.—No Federal banking agency may engage in any activity concerning or related to the regulation, supervision, or examination of the reputational risk, or any term substantially similar, or the management thereof, of a depository institution, including—

(A) establishing any rule, regulation, requirement, standard, or supervisory expectation concerning or related to the reputational risk, or any term substantially similar, or the management thereof, of a depository institution whether binding or not;

(B) conducting any examination, assessment, data collection, or other supervisory exercise concerning or related to reputational risk, or any term substantially similar, or the management thereof, of a depository institution;

(C) issuing any examination finding, supervisory criticism, or other supervisory or examination communication concerning or related to reputational risk, or any term substantially similar, or the management thereof, of a depository institution;

(D) making any supervisory ratings decision or determination that is based, in whole or in part, on any matter concerning or related to reputational risk, or any term substantially similar, or the management thereof, of a depository institution; and

(E) taking any formal or informal enforcement action that is based, in whole or in part, on any matter concerning or related to reputational risk, or any term substantially similar, or the management thereof, of a depository institution.60

Establishing this process will both take reputational risk factors off the table and create a much-needed paper trail should concerns arise again.

Removing Incentives to Debank

Congress should also reform the larger Bank Secrecy Act regime.61 While the costs of this system have been evident in the cases of accounts closed, the money spent on compliance, and the privacy lost, the government has yet to provide compelling evidence that these impositions deliver meaningful benefits.62 Repealing the Bank Secrecy Act, repealing the reporting requirements, or even just reforming the reporting requirements could all go a long way in changing the incentives financial institutions face.

Congress has three options when it comes to removing these incentives. First, at a minimum, all the thresholds for reports required under the Bank Secrecy Act should be adjusted for inflation. For example, the $10,000 currency transaction report threshold should be adjusted to at least $86,000 to account for the inflation that has taken place since the Bank Secrecy Act was first passed in 1970. Some members of Congress have introduced legislation in recent years to move toward this goal, but more support is needed to make this change a reality.

Legislative language that would make the full adjustment reads as follows:

The Secretary of the Treasury (referred to in this section as the “Secretary”) shall take the following actions:

(1) Not later than 180 days after the date of enactment of this Act, the Secretary shall—

(A) amend part 1010 of title 31, Code of Federal Regulations, or any successor regulations, such that, with respect to each instance in that part in which the threshold for filing a transaction in currency is more than $10,000, such threshold becomes more than $86,000;

(B) amend section 1020.320(a)(2) of title 31, Code of Federal Regulations, or any successor regulation, by striking “$5,000” and inserting “$11,000”;

(C) amend section 1022.320(a)(2) of title 31, Code of Federal Regulations, or any successor regulation, by striking “$2,000” and inserting “$4,000”;

(D) amend section 1022.320(a)(3) of title 31, Code of Federal Regulations, by striking “$5,000” and inserting “$10,000”;

(E) amend section 1010.306 of title 31, Code of Federal Regulations, by striking “$10,000” and inserting “$86,000”;

(F) amend section 1010.330 of title 31, Code of Federal Regulations, by striking “$10,000” and inserting “$30,000”;

(G) amend section 1010.340 of title 31, Code of Federal Regulations, by striking “$10,000” and inserting “$86,000”; and

(H) amend section 1.6050I‑1 of title 26, Code of Federal Regulations, by striking “$10,000” and inserting “$31,000.”

(2) With respect to each amount amended under paragraph (1), the Secretary shall adjust that amount annually to reflect the annualized percentage increase in the personal consumption expenditures price index, as indicated in the Gross Domestic Product, Fourth Quarter report released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis of the Department of Commerce for the applicable year (referred to in this section as the “BEA report”), which the Secretary shall round to the nearest $1,000.

(3) The Secretary shall provide that each adjustment described in paragraph (2) shall be made on the date that is 30 days after the date on which the applicable BEA report is released.

Yet, adjusting the thresholds is akin to treating the symptom instead of the cause. The Fourth Amendment does not say that people have a right to be secure in their papers unless it involves a lot of money. For its second option, Congress should eliminate the reporting requirements entirely. If such a change were made, law enforcement could still go after actual criminals. They would just need to get a warrant to prove they have a legitimate need for someone’s records. To do so, Congress should first repeal 31 U.S.C. Sections 5313–16, 31 U.S.C. Section 5318(a)(2), 31 U.S.C. Section 5318A, 31 U.S.C. Section 5324, 31 U.S.C. Section 5326, 31 U.S.C. Sections 5331–32, 31 U.S.C. Section 5336, 31 U.S.C. Sections 5341–42, 31 U.S.C. Sections 5351–55, 26 U.S.C. Section 6050I, 12 U.S.C. Section 3413(b)–(r), 12 U.S.C. Section 3414, and 12 U.S.C. Section 3402(2), (4), and (5).63

To amend the remaining pieces, Congress should use the following language64:

Declaration of Purpose.—Subchapter II of chapter 53 of title 31, United States Code, is amended by striking section 5311 and inserting the following:

(1) Ҥ 5311. Declaration of purpose

“It is the purpose of this subchapter (except section 5315) to—

(A) require financial institutions to retain transaction records that include information identified with or identifiable as being derived from the financial records of particular customers.”

Even then, eliminating half the regime would not solve all the problems. Issues including know-your-customer requirements, transnational repression, derisking, and debanking all tie back to these laws.65 Therefore, the third option for Congress is to repeal the entire Bank Secrecy Act regime. That would permit banks to decide what information they need, whom they do business with, and what risks they take on. It would still be illegal to knowingly assist criminal activity, and law enforcement would still be able to get a warrant should an investigation justify it.

Conclusion

Debanking is difficult to address. Between layers of confidentiality and the sensitivity of financial relationships, fully understanding what’s taking place is difficult. That is why Congress should prioritize limiting the government’s role in debanking and promoting the transparency needed to understand the full scope of debanking.

Citation

Anthony, Nicholas. “Understanding Debanking: Evaluating Governmental, Operational, Political, and Religious Financial Account Closures,” Policy Analysis no. 1009, Cato Institute, Washington, DC, January 8, 2026.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.