In keeping with Capitolism tradition, my first column of 2026 will examine some of my big, open questions for the coming year—questions that could have significant economic policy implications but don’t yet have solid answers. I think my previous questions from 2023, 2024, and 2025 hold up well, so hopefully these will too. (Even if they don’t, they’ll still give you an idea of some of the things I’ll be watching and writing about this year.)

Before we begin, a small programming note: After more than five years of almost-weekly dives into a sea of policy issues, Capitolism will be stepping back a bit in 2026 due to various other work obligations and my intense desire to stay somewhat sane and rested. Thus, I’ll be writing this newsletter every other week for the foreseeable future. Given that I tend to cover a few core issues and that I rarely chase news cycles, this change should, I think, have only a modest effect on what regular readers will learn each year (and, with a little more time for thought and analysis, it might even improve the overall content). That said, this is admittedly a significant change, so I wanted to mention it.

And with that, let’s get started.

So, Now What?

It might be a cop-out to put the U.S. economy’s trajectory as my No. 1 policy question for 2026, but last year basically demands it. The prolonged government shutdown and standard reporting lags mean that we still don’t have rock-solid economic data for the last few months of 2025. November’s surprisingly tame inflation report, for example, is probably wrong because it inexplicably lacked housing cost data, and future reports will likely be affected, too. Economists also expect significant data-related revisions to the solid third-quarter GDP report that came out right before Christmas. And several other important economic reports, originally scheduled for late 2025, still haven’t been published. So, from a simple reporting perspective, there’s still a ton of shutdown fog obscuring how the U.S. economy finished out 2025.

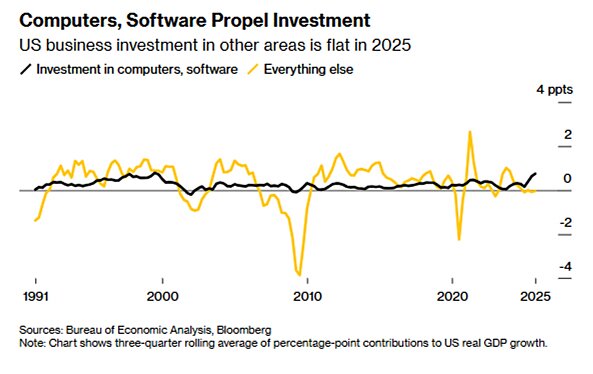

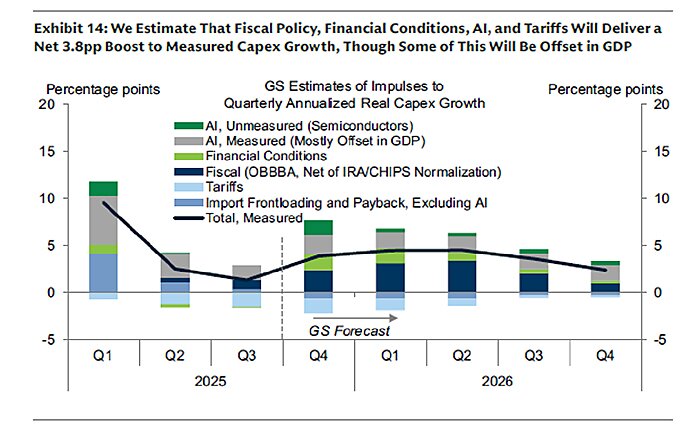

The data we do have, meanwhile, reveal a very mixed bag (contrary to partisan cheerleaders and doomsayers alike). On the one hand, consumer spending and nonresidential business investment have remained strong enough this year to more than offset drags from sagging residential construction and high tariffs (which, yes, have been a real drag). Tech-related investment has been particularly solid because of the AI boom (and tariff exemptions for basically everything U.S. AI companies need):

Productivity in the U.S. continues to be the envy of the developed world—also owed in part to the continued adoption of AI across many American industries. Wealth effects from housing and a still-strong stock market have been another tailwind, especially through the fall.

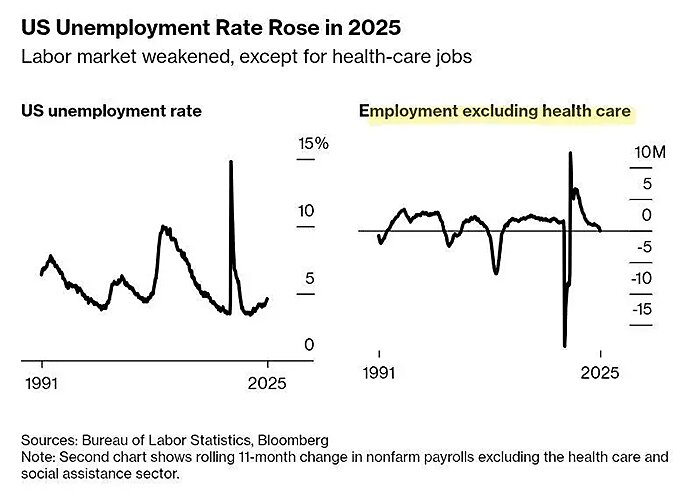

The data also show, however, several reasons for concern. Most notably, the U.S. labor market is basically treading water, with unemployment ticking up and private payrolls eking out a small annual gain thanks mainly to the health care sector:

Both hiring and firing have been subdued, signaling employer trepidation and softening economic activity; small businesses are shedding workers; and blue-collar job growth has been particularly lousy:

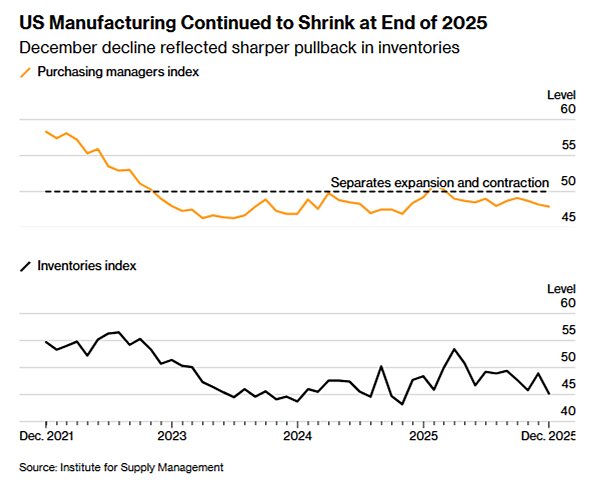

Consumer sentiment, meanwhile, is in the toilet (not only among Democrats); business bankruptcies are at 15-year high; profit margins are looking compressed; manufacturing is stagnant, at best; and inflation, while cooling, is still significantly higher than the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target. In each case, including with jobs, tariffs appear to be playing a role, and deportations probably are too. As we’ve discussed repeatedly, however, those policy mistakes alone won’t tip the big, dynamic U.S. economy into a recession. They’re just misguided and needless economic headwinds.

Put it all together, economist Dave Herbert documented right before Christmas, and you have an unsettled and foggy U.S. economy that definitely didn’t stink last year, but also wasn’t the “golden age” that President Donald Trump promised us, either. Assuming the most recent (and optimistic) inflation and GDP are unchanged and carry through the end of the year—both big assumptions—annual economic growth for 2025 would be about 2.47 percent. That’s better than many expected back in the spring (though an outright recession was never the consensus view), but it’s also a few ticks below the growth we had in 2024. (The same general conclusion follows for other, less-distorted measures of U.S. economic output, too.) And if fourth-quarter GDP disappoints, last year’s growth could be even slower.

These mixed economic signals—plus the data issues, big 2026 tax policy changes, and continued uncertainty surrounding trade and Trump’s pick for Federal Reserve chair—make predicting the U.S. economy’s near-term trajectory even more difficult than usual. (The top economic forecasters, for example, agree that the U.S. will see continued growth this year, but there is “considerable disagreement” and “it is essentially a coin toss” on whether forecasters will hit their marks.) With the Trump administration promising that their policies will deliver big economic wins this year and with midterm elections ramping up and voters still obsessed with inflation and the economy, it’d be malpractice not to list this very unsettled issue as among the biggest (if not the biggest) question of the year. Buckle up.

Tariffs, Sure, But How?

One thing we do know about 2026 is that tariffs will once again be a top-of-mind policy issue (much to my chagrin). Beyond that, however, lies a trove of open questions. In the coming days, for example, the Supreme Court will rule on the legality of Trump’s “emergency” tariffs, which, U.S. customs data show, constituted approximately 60 percent of all duties collected through mid-December of last year. If the court invalidates those duties—an outcome that informed observers (and betting markets) still view as likely—there’ll be huge questions about how (not whether) the administration re-creates the president’s tariff walls, how the federal government will refund the tens of billions of dollars it would owe to U.S. importers, and how the U.S. economy, multinational corporations and investors, and foreign trading partners will respond to the court’s ruling and Trump’s reactions thereto. We have some clues for each issue, but—as we learned all too well in 2025—it’d be foolish to assume that things will go according to script.

These are not, however, the only open tariff questions for 2026. As already discussed, for example, there’s still a ton of uncertainty surrounding the economic effects of Trump’s tariffs—both last year and (especially) going forward. Beyond simply getting the data we need to assess what’s happened so far, will U.S. companies pass on the costs they’ve thus far been absorbing? Will they invest more here to avoid tariff costs, or will they move offshore to lower-cost places so they can better service key export markets? And how will continued uncertainty affect foreign investment that’s supposedly been goosed by all those trade deals? The list goes on.

There are also many nagging policy questions. Will various exemptions and loopholes—which cut the actual U.S. tariff rate to around half the announced rate but also ramped up the distortions—be closed or expanded, especially for well-connected and politically important corporations? Will pending “national security” tariff investigations ever get finished? Will all those “trillions” in foreign investment from Japan, Korea, and others—which many have speculated were more stalling tactic than financial reality—start to flow, and will they give Trump more opportunities to take equity stakes in companies? Will tariff tensions imperil the USCMA negotiations scheduled for later this year? And how will the rest of the world continue to respond to Trump’s trade onslaught?

As we’ve discussed—and as new data show—the global economy has proven remarkably resilient in the face of Trump’s tariff onslaught, thanks to both creative corporate maneuvering (inventory front-loading, supply chain adjustments, etc.) and foreign governments’ refusal to follow Trump’s protectionist lead (instead moving to keep the U.S. at arm’s length and trade more with each other). How these trends continue to shake out will be one of the more important things to watch in 2026, as will how Trump responds if his core tariff objectives—significantly cutting the trade deficit, boosting manufacturing investment and jobs, etc.—aren’t achieved. Given the direction of things so far (see next issue), that last tariff question might be the most important one of all.

Is 2026 U.S. Manufacturing’s Make-or-Break Year?

Last year, I skeptically asked whether 2025 would be the year that “Bidenomics” industrial subsidies would combine with Trump 2.0 tax and deregulatory moves to help American manufacturing get its groove back. The answer through December—even acknowledging that sagging factory employment is a poor indicator of the industry’s overall health—has been a resounding “nope.”

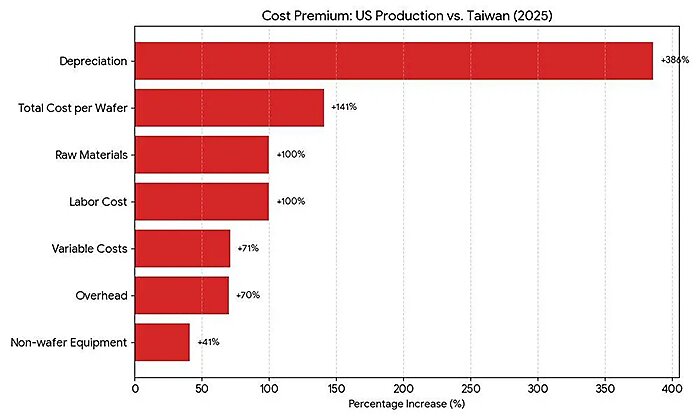

Many of the reasons for the sector’s continued doldrums come right out of previous Capitolism editions (and Econ 101 textbooks). Discrete industrial policy wins have been costly, prematurely celebrated, and offset by losses elsewhere in the U.S. economy (owed in part to the inherent uncertainty baked into a system dictated by politics and elections rather than markets). Trump’s blanket and byzantine tariffs, meanwhile, have helped some U.S. manufacturers but saddled far more—especially small and medium-sized firms—with higher production costs, increased compliance burdens, and diminished global competitiveness. And any modest tariff benefits have been further muted by the uniquely erratic and complex nature of Trump’s unilateral levies. Indiscriminate deportations and new U.S. immigration restrictions are also causing problems by tempering demand and by straining an industrial labor market that was already struggling to find warm bodies. Overall, it’s a recipe for not the immediate boom the administration promised last spring but continued manufacturing stagnation. And that’s basically what we got.

Unsurprisingly, administration officials and their protectionist allies have now pivoted to promising us that, actually, 2026 will be the year American manufacturing is made great again. And they do have a few points in their favor. New and extended corporate tax provisions in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (aka “full expensing”) should—along with lower interest rates, lighter regulatory scrutiny, and continued adoption of AI—encourage more domestic manufacturing investment and output. If SCOTUS invalidates the IEEPA tariffs, big refunds might goose corporate balance sheets, and investment-dampening policy uncertainty should modestly abate (but mainly because it can’t get much worse!). Maybe some of those foreign investments actually do happen (though it won’t be “trillions,” sorry); maybe a weaker dollar—itself a policy question—helps some U.S. exporters sell more abroad; and maybe political concerns about the midterms and “affordability” discourage more trade hostilities. Maybe.

Regardless, one thing is clear: A revived U.S. manufacturing sector in 2026 wouldn’t be because of Trump’s tariffs, but in spite of them.

Viva, Argentina?

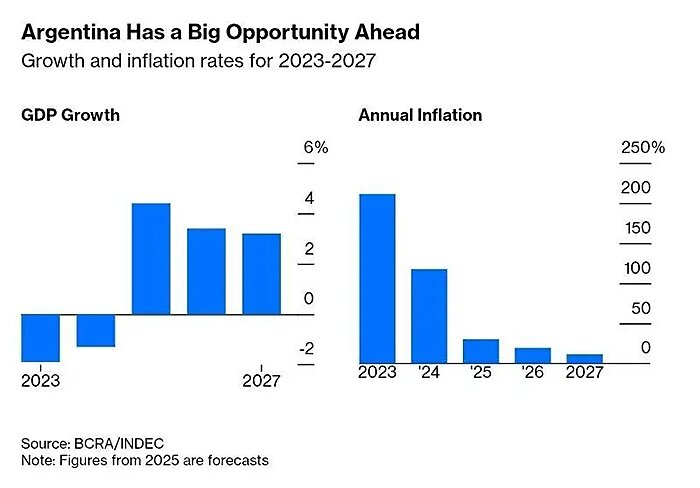

It may have been unconventional and more than a bit concerning, but Javier Milei’s gamble on a Trump administration currency backstop seems to have paid off with a resounding election win in October that gave him a mandate to continue Argentina’s thus-far-successful “free market revolution.” Markets have responded to the win—and the prospects for even deeper reforms now that Milei’s party is more firmly in charge—very favorably, and forecasts for both growth and inflation are looking good:

There are surely challenges ahead—currency, included—but something really does seem to be afoot in the country. As Bloomberg reported in December, Milei’s popularity is back on the upswing thanks in large part to his embrace of markets and fiscal sanity. Meanwhile, “the share of Argentines who say they would rather live in a country where the state does most things rather than private companies has fallen from 70% in 2011 to 41% this year.” ¡Afuera!

If Milei’s success is cemented in 2026, Argentina might really (and shockingly) become a free-market blueprint for the world. So, of course, I’ll be watching with both fingers crossed.

Will Housing Rebound (and Take the U.S. Consumer With It)?

It has been a brutal three-year stretch for the U.S. housing market, with homebuilding, inventories, and sales down and prices and mortgage rates up (way up). But we may have turned a corner in the fall, as lower rates, more supply, and easing prices caused home sales in all regions to climb in November—conditions that are expected to continue into the new year. As Bloomberg’s Conor Sen reports, in fact, “Resale housing inventory has climbed toward or above pre-pandemic levels in most of the South and West,” and this—along with improvements in the rest of the country—should continue through 2027. These dynamics are tilting the market back toward buyers, including young ones:

This normalization is putting gradual but persistent pressure on prices. At a metro level, price growth is either decelerating or prices are outright falling just about everywhere. A surge in delistings heading into year-end indicates that market dynamics are weaker than advertised home prices suggest. The S&P Cotality Case-Shiller US National Home Price Index rose just 1.3% in September from a year ago, well below the 3.7% growth in the average hourly earnings of American workers.

Throw in the fact that many boomers are starting to age out of their homes, Sen notes, and the outlook for Gen Z homebuyers is pretty good—especially in places that allow homebuilders to actually build (see Charts of the Week below). None of this means we’re returning to the “cheap” years of the 1990s or the rock-bottom mortgage rates of the last decade-plus—and continued NIMBY opposition, bad local regulation, and tariffs on construction materials certainly won’t help. But a “return to housing normalcy” could very well be in the cards for 2026, at least on a national level. That would be great news, if so, and with homeownership a constant political issue and likely driver of recent consumer grumpiness (not to mention bad populist policies like rent control), an important political matter, too.

What’s Next for State Corporatism?

Capitolism concluded last year on a sour note about the federal government’s radical and unprecedented push into the daily affairs of numerous private companies. What happens next will be just as important. Will these new national champions grow with Washington backstopping their operations, in the process siphoning finite resources away from incumbent competitors and new market entrants? Will the administration take a more active role in the companies’ operations, like it recently did by prodding U.S. Steel to reopen a decaying Granite City plant that should’ve been shuttered a decade ago? Will customers, investors, and foreign governments seek to do business with government-backed firms to curry favor with the administration or to otherwise influence U.S. policy? Will other companies try to lobby the president into backing them too, or to prevent their competition from getting a federal thumb on the scale? Will the administration give the companies additional favors—subsidies, contracts, regulatory preferences, whatever—to cement their near-term success (or, at the very least, to keep their share prices inflated)? Will there even be enough transparency and data for outside observers to know what’s going on?

And will this and other executive branch adventurism—on trade, immigration, or any number of non-economic issues (ahem, Venezuela)—finally push our long-dormant Congress to exert even a modicum of its express constitutional powers?

On second thought, that last one is probably a better question for 2027.

Chart(s) of the Week