The number and impact of natural disasters are increasing because of climate change and more people living in urban areas (Sanderson and Sharma 2016). The mechanism is simple, at least when considering climatic events: higher temperatures lead to higher rates of water evaporation, which increases the chance of flooding events (Wallace et al. 2014; IPCC 2001). The number of hot days has increased and the number of cold days has decreased in land areas, with model projections indicating that extreme precipitation events will continue to increase, resulting in more floods and landslides. At the same time, mid‐continental areas will get dryer, which will increase the chance of droughts and wildfires (Van Aalst 2006). The course of action taken by humanity in the next decades will likely play a pivotal role since extreme differences in projections are expected if global temperatures rise 2°C in comparison to 1.5 °C above preindustrial levels (Allen et al. 2019). What are the economic impacts of natural disasters? This question has been addressed to a large extent in the literature, but it still does not have a conclusive response. The seemingly natural reasoning that destruction cannot lead to a net benefit for society was explained almost two centuries ago by Bastiat (1850) in his famous broken window fallacy. A shopkeeper’s son, Bastiat relates, breaks a pane of glass in his father’s store. The father, angry due to the boy’s careless action, is offered consolation by the spectators, who claim that the event is positive for the economy since it provides labor to glaziers. While Bastiat acknowledges that the accident brings trade to the glazier since the shopkeeper has to replace the window, regarding the event as wealth‐increasing conveys a narrow perspective. The shopkeeper ends up poorer since he cannot spend the same money elsewhere, and if the boy had not broken the window, then the labor and other materials that were used to repair the damage would have been used elsewhere, potentially making the tangible wealth of the community grow.

As reasonable as Bastiat’s argument might sound, it is not clear if natural disasters, or any destructive event for that matter, should affect economic growth and in which direction it might do so. There is a difference in the predictions that an economist would obtain with neoclassical growth models and certain endogenous growth models. While the former theorizes that a natural disaster—that is, a negative shock to capital or both to capital and labor—decreases output in the short run, it does not affect the steady‐state of the economy in the long run. Neoclassical models also predict that the destruction of the capital stock will temporarily accelerate growth immediately after the disaster by increasing the marginal return on capital. On the other hand, some endogenous growth models based on Schumpeterian creative destruction can predict an overall higher growth rate produced by an accelerated replacement of the capital stock with more productive capital, as is the case in vintage capital models (Hallegatte and Dumas 2009).

Given the extensive debate regarding natural disasters and economic growth, in an attempt to shed light on the mechanisms by which these destructive events affect the economy, we ask whether economic institutions and, in particular, economic freedom, is relevant for obtaining a higher rate of economic growth, independent of whether this growth is positive or negative. There are not many articles that have studied the relationship between institutions and economic growth after natural disasters. In our review of the literature, we found the following published articles: Felbermayr and Gröschl (2014), Barone and Mocetti (2014), Raschky (2008), and Kahn (2005). Our objective is to expand on this literature by emphasizing the role of economic freedom as a relevant factor in explaining the economic recovery process in the aftermath of disasters, which is increasingly relevant today given the climate change projections for the next decades. As the frequency of natural disasters increases and their economic impact in society can be ameliorated with better institutions, it becomes imperative to find out, with as much precision as possible, which institutions are relevant and what policies can be put in place to lessen the destruction.

In the following section, we discuss the relevant literature regarding the impact of natural disasters on output and the role of institutional measures. Then we describe our methods and data, present the regression results, and offer some concluding comments.

Literature Review

Natural disasters are a topic that has been studied extensively in the scientific literature. Over 6,000 articles matching the topic “natural disasters” are registered in the Web of Science core collection. The body of literature that focuses on economic growth is much smaller, with 136 articles matching search results for “natural disasters” and “economic growth” at the same time.1 Instead of attempting to provide a general perspective regarding this literature, we focus on the few articles that study the effects of institutions and their relationship with economic activity after a natural disaster (Felbermayr and Gröschl 2014; Barone and Mocetti 2014; Raschky 2008; Kahn 2005) and discuss their findings.

Felbermayr and Gröschl (2014), in a growth model that shows that disasters are negatively correlated with growth, included two institutional variables in their analysis: measures of democracy (polity index) and trade openness. They found that only the latter is significant in reducing the negative economic impact of natural disasters. Barone and Mocetti (2014) focused on whether the quality of institutions affect subsequent growth in GDP per capita after an earthquake by performing a case study of two Italian regions. They construct what they call an “overall institutional quality index,” which they estimate through a principal component analysis based on four local variables: corruption levels, the share of politicians involved in scandals, electoral turnout, and newspaper readership. The authors found that the region with the higher institutional quality index experiences faster growth after the disaster.

In a cross-country setup, Raschky (2008) studied the relationship between economic development and vulnerability to natural disasters, suggesting that although economic development reduces the number of disaster victims and the amount of economic losses, increasing wealth inverts the relationship and causes higher losses. He concluded that higher income does not necessarily lead to better protection against disasters. As a secondary research question, he addressed the importance of institutional quality as a socioeconomic factor that provides protection against natural hazards, for which he used data on governmental stability and the investment climate, which are institutional measures from the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG). Raschky found that both measures, government stability and investment climate, have a significant impact on reducing the death toll and economic losses from natural disasters. In a similar line, Kahn (2005) studied whether institutions are relevant for predicting the death toll from disasters by examining the impact of the Polity index from Systemic Peace and the World Governance Indicators from the World Bank. He determined with borderline significance that ceteris paribus, democracies experience less death from disasters, which he attributes to the fact that democracies have greater accountability and less corruption. As for the World Governance Indicators, which include measures of property rights, democracy, regulatory quality, voice and accountability, rule of law, and control of corruption, Kahn finds an overall positive correlation with less death by disasters.

The importance of institutions for economic growth has been established since North (1991), who was the first to explain how institutions provide the incentive structure of an economy (see also Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson 2005). Knowing the rules of the game and being confident that those rules will be enforced is a key component for growth, and factors such as property rights, regulation, inflation, civil liberties, political rights, freedom of the press, government expenditures, and trade barriers have all been linked to growth in empirical studies (Talbott and Roll 2001).

The structure of property rights is a critical economic institution and, therefore, an essential factor underlying growth. With poor property rights, individuals will have little incentive to invest in physical or human capital, which is a larger problem after a natural disaster since a portion of the capital stock has been destroyed and, therefore, the incentives to increase it are higher. It is also likely that a society with more disregard for property rights will have a higher incidence of looting behavior after a disaster, which is detrimental to the recovery process.

A mechanism commonly presented in the empirical literature that is used to explain the positive effects of natural disasters is the accelerated replacement of the existing capital stock with more productive capital, which causes a faster embodiment of new technologies and temporarily accelerates growth (Albala-Bertrand 1993; Skidmore and Toya 2002). In Hallegatte and Dumas (2009), this mechanism is referred to as the “productivity effect” and is investigated in detail in a Solow-like model with embodied technological change. Without this mechanism, one way to explain higher economic growth after a natural disaster is by the higher amount of government spending in the aftermath of the disaster. An economic boom can occur driven by the construction sector (Benson and Clay 2004). However, spending will be easier to finance if institutions that value sound fiscal policy are present. If a country has an unbalanced budget with a high deficit and sustained debt, then financing the costs of reconstruction will increase the deficit and debt level even more, which is associated with lower levels of growth (Checherita-Westphal and Rother 2012).

Entrepreneurship activities have been increasingly linked to natural disasters, with recent evidence suggesting that they decrease start-up activity in the next two years after a disaster (Boudreaux, Escaleras, and Skidmore 2019), although they have also been shown to be correlated with an increase on entrepreneurial intention (Monllor and Murphy 2017).

The relationship between entrepreneurship and disasters is relevant given the link between entrepreneurial activity, economic growth, and institutions. An atmosphere that promotes strong economic institutions is also favorable for entrepreneurship (Larroulet and Couyoumdjian, 2009), which is a fundamental driver for growth, especially after a disaster in which there is significant destruction of the capital stock.

Methods and Data

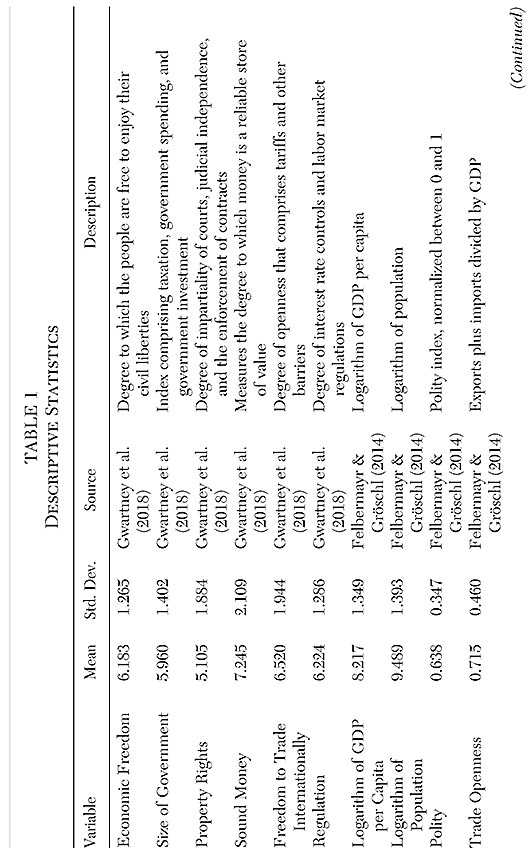

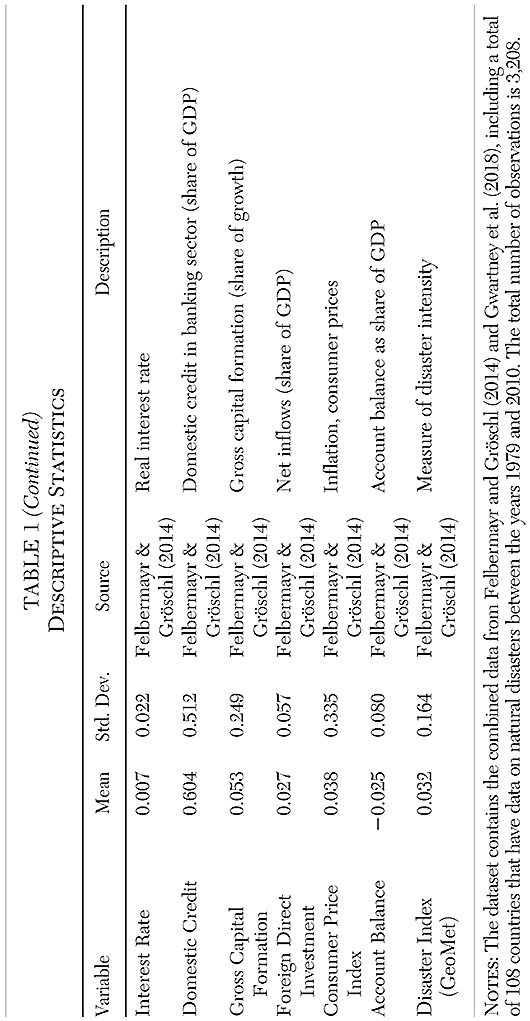

We use publicly available data from two different sources for our regression model, GeoMet for economic and disaster variables (Felbermayr and Gröschl 2014), and the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom Index for institutional quality, which includes the size of government, property rights, sound money, freedom to trade internationally, and regulation.2 The reason behind using these institutional variables as opposed to, for example, the World Governance Indicators by the World Bank, is that the Fraser Institute’s variables start further back in time, beginning on a quinquennial basis since 1970 and yearly since 2000, while the data from the World Governance Indicators starts at 1996. We also include the Polity index in our analysis as a measure of the democracy level, for which yearly data are available throughout the entire period in question. Table 1 shows a description of the variables used as well as the sample mean and standard deviation for each.

Following Felbermayr and Gröschl (2014), we use a standard growth regression framework. The units of observation are country-year combinations. We include lagged GDP per capita to estimate a dynamic model, a disaster measure, several control variables, and the economic freedom institutional indexes. Our basic specification takes the following form:

(1) Δln yi,t = (ρ — 1) ln yi,t21 + α Ii,t21 + β Di,t + γ Xi,t21 + ∊i,t,

where yi,t is the GDP per capita of country i at time t, Dln yi,t is the growth rate of GDP per capita at time t, and Ii,t21 is the set of institutional variables included, that is, the Polity index and the Economic Freedom Index, indexed for country and year and lagged one period. Di,t is a yearly measure of disaster intensity, encompassing the disasters that occurred in the country i at time t, as constructed by Felbermayr and Gröschl and available in GeoMet. Finally, Xi,t21 include the following group of control variables: the logarithm of population, trade openness, the real interest rate, domestic credit in the banking sector (as a share of GDP), gross capital formation (as a share of growth), foreign direct investment (as a share of GDP), the logarithm of the inflation rate, and the current account balance (as a share of GDP).3

We use the extended version of the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT), GeoMet, for disasters data between the years 1979 and 2010, and the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom Index database, which has data from 1970 onward. Combining these datasets, we are left with a panel of 90 countries to run our main regression model. As the data on economic freedom before the year 2000 are available only once every five years until 1970, the data are interpolated to be used in our regression model for the period 1979–2010.

Most disaster studies use the EM-DAT Database, but as has been noticed by Felbermayr and Gröschl (2014), there might be an inclusion bias in the database (see Strobl 2012). The problem is that the probability of inclusion could be correlated with income. Even more troublesome is the fact that direct damage might not be a reliable measure of disaster intensity. Monetary damage, or variables correlated to it, are higher in a richer economy after a disaster, which is why they are not reliable variables to be used in growth regressions. Felbermayr and Gröschl (2014) put together GeoMet to account for this issue, which is why their measure of disaster intensity, D(i,t), the same one we use in our regressions, does not depend on estimations of monetary damage but on direct exogenous measures of disaster intensity, as Richter magnitude for earthquakes, wind speed for storms, precipitation level for floods, and temperature level for extreme temperatures events.

Results: Regression Analysis

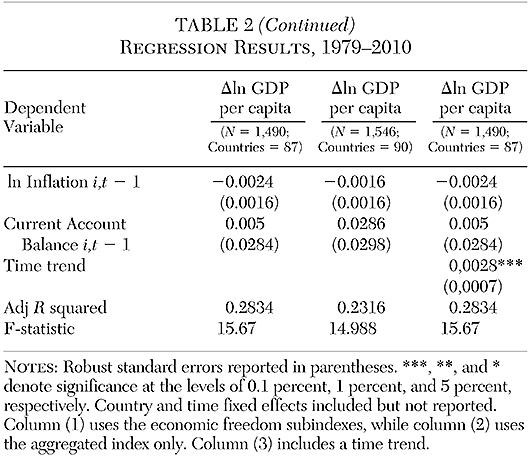

We present the results of our regression model in Table 2.4 The disaster index variable is an unweighted sum of the physical intensity measures of disasters that happened in a specific country in a specific year divided by the log of the area of the affected country to account for country size. The empirical analysis indicates that a country with a higher quality of institutions, which is expressed in the economic freedom indexes as higher values of all variables except for size of government, are more favorable for economic growth. Countries with higher economic freedom will be able to respond more effectively to an exogenous shock to capital and labor, achieving higher economic growth immediately after a natural disaster.

Our results regarding the disaster index in growth in GDP per capita are in line with Felbermayr and Gröschl (2014), which is expected since we use the same disaster index variable. Quantitatively, looking at our main specification in column (1) of Table 2, since the estimated coefficient for the disaster index is 20.0556 and the sample mean of the index is 0.032, in a year in which the index is equal to the mean, economic growth will be lower by 0.18 percent. Considering a stronger natural disaster (i.e., a disaster that is one standard deviation higher in the GeoMet index), we can tell by the estimated coefficient that growth in the year of the disaster, ceteris paribus, will be 1.1 percent lower.

Concerning the institutional variables from the Fraser Institute, we find significant effects for property rights and freedom to trade internationally at 0.1 percent significance, and borderline significance for the regulation component of the index at the 10 percent level. The property rights component of the index has a sample mean of 5.105, which means that, on average, a country with the mean level of property rights will grow by 3.27 percent, and a 1 point decrease will cause growth to decline to 2.63 percent. Regarding freedom to trade internationally, a country with the sample mean value of 6.520 will have an average yearly growth of 3.39 percent, and a 1 point decrease from the mean level will decrease growth to 2.87 percent. Lastly, regulation has a regression coefficient of 0.0052, which means that based on its sample mean level of 6.224, the yearly growth after a natural disaster is 3.23 percent, and a 1 point decrease will cause growth to decline to 2.72 percent.

In column 3 of Table 2, we include a time trend to account for linear growth in the time series. The coefficient is statistically significant at the 0.1 percent level and positively impacts growth, indicating that countries are on average increasing their economic growth in the data. Comparing our three regression specifications in Table 2: with or without the individual economic freedom components, and with or without a time trend, we find that our main results hold, that is, that economic freedom is relevant and causes a positive and statistically significant effect in economic growth after natural disasters.

Conclusion

Performing a fixed-effects regression clustered at the country level and using the growth of GDP per capita as the dependent variable, we found evidence that natural disasters reduce growth in real GDP per capita in the year that they occur and that institutions, specifically property rights and freedom to trade internationally, reduce their negative impact.

The regression coefficients express the magnitude of the effect of institutional variables on GDP per capita. We find that a 1 point drop in the property rights index causes growth to decline by 0.64 percent after a natural disaster. Regarding freedom to trade internationally, a 1 point drop decreases growth in income by 0.52 percent. We do not find the level of democracy to be relevant for economic growth after a natural disaster according to the Polity index as its coefficient is not significant in our specifications, nor are the economic freedom components related to the size of government or sound money.

The analysis suggests policy recommendations regarding the importance of institutions. Increasing economic freedom, property rights or freedom to trade internationally attenuates the negative impact of a natural disaster. In the same way, it may improve the indirect positive impact of fiscal spending in economic growth after a disaster.

References

Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; and Robinson, J. A. (2005) “Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth.” Handbook of Economic Growth 1 (Part A): 385–472.

Albala-Bertrand, J. M. (1993) Political Economy of Large Natural Disasters: With Special Reference to Developing Countries. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Allen M. R. et al. (2019) “Technical Summary.” In Masson-Delmotte et al. (eds.), Global Warming at 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C above Pre-Industrial Levels … and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty.” Geneva: World Meteorological Organization. Available at www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/02/SR15_TS_High_Res.pdf.

Barone, G., and Mocetti, S. (2014) “Natural Disasters, Growth and Institutions: A Tale of Two Earthquakes.” Journal of Urban Economics 84 (November): 52–66.

Bastiat, F. ([1850] 1964) “What Is Seen and What Is Not Seen.” In Selected Essays on Political Economy, chap. 1. Edited by G. B. de Huszar; translated from the French by S. Cain. Irvington-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Foundation for Economic Education.

Benson, C., and Clay, E. J. (2004) Understanding the Economic and Financial Impacts of Natural Disasters. Washington: World Bank.

Boudreaux, C. J.; Escaleras, M. P.; and Skidmore, M. (2019) “Natural Disasters and Entrepreneurship Activity.” Economics Letters 182: 82–85.

Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (2015) EM-DAT: The OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database. Brussels, Belgium: Catholic University of Leuven.

Checherita-Westphal, C., and Rother, P. (2012) “The Impact of High Government Debt on Economic Growth and Its Channels: An Empirical Investigation for the Euro Area.” European Economic Review 56 (7): 1392–405.

Felbermayr, G., and Gröschl, J. (2014) “Naturally Negative: The Growth Effects of Natural Disasters.” Journal of Development Economics 111 (November): 92–106.

Gwartney, J.; Lawson, R.; Hall, J,; and Murphy, R. (2018) Economic Freedom of the World: 2018 Annual Report. Vancouver, B.C.: Fraser Institute.

Hallegatte, S., and Dumas, P. (2009) “Can Natural Disasters Have Positive Consequences? Investigating the Role of Embodied Technical Change.” Ecological Economics 68 (3): 777–86.

IPCC ( (2001) “Summary for Policymakers.” In R. T. Watson et al. (eds.), Climate Change 2001: Synthesis Report. New York: Cambridge University Press for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Kahn, M. E. (2005) “The Death Toll from Natural Disasters: The Role of Income, Geography, and Institutions.” Review of Economics and Statistics 87 (2): 271–84.

Larroulet, C., and Couyoumdjian, J. P. (2009) “Entrepreneurship and Growth: A Latin American Paradox?” Independent Review 14 (1): 81–100.

Monllor, J., and Murphy, P. J. (2017) “Natural Disasters, Entrepreneurship, and Creation after Destruction: A Conceptual Approach.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research 23 (4): 618–37.

North, D. C. (1991) “Institutions.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 5 (1): 97–112.

Raschky, P. A. (2008) “Institutions and the Losses From Natural Disasters.” Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 8 (4): 627–34.

Sanderson, D., and Sharma, A. (2016) World Disasters Report 2016: Resilience: Saving Lives Today, Investing for Tomorrow. Geneva, Switzerland: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC).

Skidmore, M., and Toya, H. (2002) “Do Natural Disasters Promote Long-Run Growth?” Economic Inquiry 40 (4): 664–87.

Strobl, E. (2012) “The Economic Growth Impact of Natural Disasters in Developing Countries.” Journal of Development Economics 97 (1): 130–41.

Talbott, J., and Roll, R. (2001) “Why Many Developing Countries Just Aren’t.” The Anderson School at UCLA, Finance Working Paper No. 19–01.

Van Aalst, M. K. (2006) “The Impacts of Climate Change on the Risk of Natural Disasters.” Disasters 30 (1): 5–18.

Wallace, J. M.; Held, I. M.; Thompson, D. W.; Trenberth, K. E.; and Walsh, J. E. (2014) “Global Warming and Winter Weather.” Science 343 (6172): 729–30.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.