In a previous blog posting, I suggested that there is no case for capital adequacy regulation in an unregulated banking system. In this ‘first-best’ environment, a bank’s capital policy would be just another aspect of its business model, comparable to its lending or reserving policies, say. Banks’ capital adequacy standards would then be determined by competition and banks with inadequate capital would be driven out of business.

Nonetheless, it does not follow that there is no case for capital adequacy regulation in a ‘second-best’ world in which pre-existing state interventions — such as deposit insurance, the lender of last resort and Too-Big-to-Fail — create incentives for banks to take excessive risks. By excessive risks, I refer to the risks that banks take but would not take if they had to bear the downsides of those risks themselves.

My point is that in this ‘second-best’ world there is a ‘second-best’ case for capital adequacy regulation to offset the incentives toward excessive risk-taking created by deposit insurance and so forth. This posting examines what form such capital adequacy regulation might take.

At the heart of any system of capital adequacy regulation is a set of minimum required capital ratios, which were traditionally taken to be the ratios of core capital[1] to some measure of bank assets.

Under the international Basel capital regime, the centerpiece capital ratios involve a denominator measure known as Risk-Weighted Assets (RWAs). The RWA approach gives each asset an arbitrary fixed weight between 0 percent and 100 percent, with OECD government debt given a weight of a zero. The RWA measure itself is then the sum of the individual risk-weighted assets on a bank’s balance sheet.

The incentives created by the RWA approach turned Basel into a game in which the banks loaded up on low risk-weighted assets and most of the risks they took became invisible to the Basel risk measurement system.

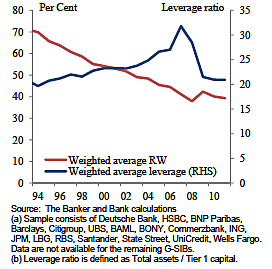

The unreliability of the RWA measure is apparent from the following chart due to Andy Haldane:

Figure 1: Average Risk Weights and Leverage

This chart shows average Basel risk weights and leverage for a sample of international banks over the period 1994–2011. Over this period, average risk weights show a clear downward trend, falling from just over 70 percent to about 40 percent. Over the same period, bank leverage or assets divided by capital — a simple measure of bank riskiness — moved in the opposite direction, rising from about 20 to well over 30 at the start of the crisis. The only difference is that while the latter then reversed itself, the average risk weight continued to fall during the crisis, continuing its earlier trend. “While the risk traffic lights were flashing bright red for leverage [as the crisis approached], for risk weights they were signaling ever-deeper green,” as Haldane put it: the risk weights were a contrarian indicator for risk, indicating that risk was falling when it was, in fact, increasing sharply.[2] The implication is that the RWA is a highly unreliable risk measure.[3]

Long before Basel, the preferred capital ratio was core capital to total assets, with no adjustment in the denominator for any risk-weights. The inverse of this ratio, the bank leverage measure mentioned earlier, was regarded as the best available indicator of bank riskiness: the higher the leverage, the riskier the bank.

These older metrics then went out of fashion. Over 30 years ago, it became fashionable to base regulatory capital ratios on RWAs because of their supposedly greater ‘risk sensitivity.’ Later the risk models came along, which were believed to provide even greater risk sensitivity. The old capital/assets ratio was now passé, dismissed as primitive because of its risk insensitivity. However, as RWAs and risk models have themselves become discredited, this risk insensitivity is no longer the disadvantage it once seemed to be.

On the contrary.

The old capital to assets ratio is making a comeback under a new name, the leverage ratio:[4] what is old is new again. The introduction of a minimum leverage ratio is one of the key principles of the Basel III international capital regime. Under this regime, there is to be a minimum required leverage ratio of 3 percent to supplement the various RWA-based capital requirements that are, unfortunately, its centerpieces.

The banking lobby hate the leverage ratio because it is less easy to game than RWA-based or model-based capital rules. They and their Basel allies then argue that we all know that the RWA measure is flawed, but we shouldn’t throw out the baby with the bathwater. (What baby? I ask. RWA is a pretend number and it’s as simple as that.) They then assert that the leverage ratio is also flawed and conclude that we need the RWA to offset the flaws in the leverage ratio.

The flaw they now emphasize is the following: a minimum required leverage ratio would encourage banks to load up on the riskiest assets because the leverage ratio ignores the riskiness of individual assets. This argument is commonly made and one could give many examples. To give just one, a Financial Times editorial — ironically entitled “In praise of bank leverage ratios” — published on July 10, 2013 stated flatly:

Leverage ratios … encourage lenders to load up on the riskiest assets available, which offer higher returns for the same capital.

Hold on right there! Those who make such claims should think them through: if the banks were to load up on the riskiest assets, we first need to consider who would bear those higher risks.

The FT statement is not true as a general proposition and it is false in the circumstances that matter, i.e., where what is being proposed is a high minimum leverage ratio that would internalize the consequences of bank risk-taking. And it is false in those circumstances precisely because it would internalize such risk-taking.

Consider the following cases:

In the first, imagine a bank with an infinitesimal capital ratio. This bank benefits from the upside of its risk-taking but does not bear the downside. If the risks pay off, it gets the profit; but if it makes a loss, it goes bankrupt and the loss is passed to its creditors. Because the bank does not bear the downside, it has an incentive to load up on the riskiest assets available in order to maximize its expected profit. In this case, the FT statement is correct.

In the second case, imagine a bank with a high capital-to-assets ratio. This bank benefits from the upside of its risk-taking but also bears the downside if it makes a loss. Because the bank bears the downside, it no longer has an incentive to load up on the riskiest assets. Instead, it would select a mix of low-risk and high-risk assets that reflected its own risk appetite, i.e., its preferred trade-off between risk and expected return. In this case, the FT statement is false.

My point is that the impact of a minimum required leverage ratio on bank risk-taking depends on the leverage ratio itself, and that it is only in the case of a very low leverage ratio that banks will load up on the riskiest assets. However, if a bank is very thinly capitalized then it shouldn’t operate at all. In a free-banking system, such a bank would lose creditors’ confidence and be run out of business. Even in the contemporary United States, such a bank would fall foul of the Prompt Corrective Action statutes and the relevant authorities would be required to close it down.

In short, far from encouraging excessive risk-taking as is widely believed, a high minimum leverage ratio would internalize risk-taking incentives and lead to healthy rather than excessive risk-taking.

Then there is the question of how high ‘high’ should be. There is of course no single magic number, but there is a remarkable degree of expert consensus on the broad order of magnitude involved. For example, in an important 2010 letter to the Financial Times drafted by Anat Admati, she and 19 other renowned experts suggested a minimum required leverage ratio of at least 15 percent — at least five times greater than under Basel III — and some advocate much higher minima. Independently, John Allison, Martin Hutchinson, Allan Meltzer and yours truly have also advocated minimum leverage ratios of at least 15 percent. By a curious coincidence, 15 percent is about the average leverage ratio of U.S. banks at the time the Fed was founded.

There is one further and much under-appreciated benefit from a leverage ratio. Suppose we had a leverage ratio whose denominator was not total assets or some similar measure. Suppose instead that its denominator was the total amount at risk: one would take each position, establish the potential maximum loss on that position, and take the denominator to be the sum of these potential losses. A leverage-ratio capital requirement based on a total-amount-at-risk denominator would give each position a capital requirement that was proportional to its riskiness, where its riskiness would be measured by its potential maximum loss.

Now consider any two positions with the same fair value. With a total asset denominator, they would attract the same capital requirement, independently of their riskiness. But now suppose that one position is a conventional bank asset such as a commercial loan, where the most that could be lost is the value of the loan itself. The other position is a long position in a Credit Default Swap (i.e., a position in which the bank sells credit insurance). If the reference credit in the CDS should sharply deteriorate, the long position could lose much more than its current value. Remember AIG! Therefore, the CDS position is much riskier and would attract a much greater capital requirement under a total-amount-at-risk denominator.

The really toxic positions would be revealed to be the capital-hungry monsters that they are. Their higher capital requirements would make many of them unattractive once the banks themselves were to made to bear the risks involved. Much of the toxicity in banks’ positions would soon disappear.

The trick here is to get the denominator right. Instead of measuring positions by their accounting fair values as under, e.g., U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, one should measure those positions by how much they might lose.

Nonetheless, even the best-designed leverage ratio regime can only ever be a second-best reform: it is not a panacea for all the ills that afflict the banking system. Nor is it even clear that it would be the best ‘second-best’ reform: re-establishing some form of unlimited liability might be a better choice.

However, short of free banking, under which no capital regulation would be required in the first place, a high minimum leverage ratio would be a step in the right direction.

_____________

[1] By core capital, I refer the ‘fire-resistant’ capital available to support the bank in the heat of a crisis. Core capital would include, e.g., tangible common equity and some retained earnings and disclosed reserves. Core capital would exclude certain ‘softer’ capital items that cannot be relied upon in a crisis. An example of the latter would be Deferred Tax Assets (DTAs). DTAs allow a bank to claim back tax on previously incurred losses in the event it subsequently returns to profitability, but are useless to a bank in a solvency crisis.

[2] A. G. Haldane, “Constraining discretion in bank regulation.” Paper given at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Conference on ‘Maintaining Financial Stability: Holding a Tiger by the Tail(s)’, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta 9 April 2013, p. 10.

[3] The unreliability of the RWA measure is confirmed by a number of other studies. These include, e.g.: A. Demirgüç-Kunt, E. Detragiache, and O. Merrouche, “Bank Capital: Lessons from the Financial Crisis,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series No. 5473 2010); A. N. Berger and C. H. S. Bouwman, “How Does Capital Affect Bank Performance during Financial Crises?” Journal of Financial Economics 109 (2013): 146–76; A. Blundell-Wignall and C. Roulet, “Business Models of Banks, Leverage and the Distance-to-Default,” OECD Journal: Financial Market Trends 2012, no. 2 (2014); T. L. Hogan, N. Meredith and X. Pan, “Evaluating Risk-Based Capital Regulation,” Mercatus Center Working Paper Series No. 13–02 (2013); and V. V. Acharya and S. Steffen, “Falling short of expectation — stress testing the Eurozone banking system,” CEPS Policy Brief No. 315, January 2014.

[4] Strictly speaking, Basel III does not give the old capital-to-assets ratio a new name. Instead, it creates a new leverage ratio measure in which the old denominator, total assets, is replaced by a new denominator measure called the leverage exposure. The leverage exposure is meant to take account of the off-balance-sheet positions that the total assets measure fails to include. However, in practice, the leverage exposure is not much different from the total assets measure, and for present purposes one can ignore the difference between the two denominators. See Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, “Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems.” Basel: Bank for International Settlements, June 2011, pp. 62–63.