Many Americans want immigrants to “get in line.” But they cannot do so on their own. They need to get a sponsor, either a U.S. citizen family member or a U.S. employer, to petition the government to grant them permanent residency (a “green card”). Even if immigrants do obtain sponsors, there isn’t just one line to get into. Rather, immigrants have separate lines based on the type of sponsorship and their country of origin, and these lines all move at different speeds. Even two immigrants working in essentially the same position whose employer petitions for them on the same day can end up receiving their green cards decades apart if they were born different places.

How America still discriminates based on nationality

This bizarre fact is a consequence of the racist history of U.S. immigration law. In 1921, Congress created the first quota on legal immigration (the “worldwide limit” ). Three years later, it created limits for individual nationalities (the “per-country limits”). The per-country limits give each nationality a share of the worldwide limit. If nationals of a certain country use up their share of the green cards, they have to wait, and immigrants from other countries get to skip ahead of them in line. (And no, Congress made sure that immigrants can’t evade the per-country quotas by getting citizenship somewhere else. Birthplace is all that matters.)

Initially, the per-country limits openly discriminated against “undesirable” immigrants, defined as Asians, Africans, and Eastern Europeans (mostly Jews). But in 1965, Congress made the per-country limits uniform across countries. Today, no country can receive more than 7 percent of the worldwide limit in any green card category. But this reform just shifted the discrimination toward nationalities with the highest demand for green cards. The goal here was not any less racist. The debates over the law abounded with “liberals” reassuring conservatives that America wouldn’t be flooded with Asians.

In order to apply for a green card, green cards must be available under both the worldwide limit and the per-country limit for the relevant category. After their sponsors petition for them to receive a green card, immigrants wait in line to apply for the green card themselves. The State Department releases a green card bulletin every month to inform immigrants of which ones can apply that month. Immigrants whose sponsor petitioned for them before a certain date—called the “priority date”—can apply. Everyone else must continue to wait.

Right now, for example, Filipinos can apply for a green card this month if their U.S. citizen siblings petitioned for them before June 8, 1994—23 years ago. But here’s the critical point: this “priority date” tells Filipinos nothing about how long they will have to wait if their sibling petitioned for them today. If a lot fewer U.S. citizens applied for Filipino siblings after June 8, 1994, they might be able to receive their green cards a decade or more sooner than those receiving them today. However, if the number of petitions increased, then the wait could be even longer—maybe decades longer.

For example, the priority date for Filipino siblings of U.S. citizens in June 1994—when those who are today receiving their green cards started the process—was June 1977. In other words, Filipino siblings filing green card applications in June 1994 had waited from 1977 to 1994. The U.S. citizen who filed an immigrant petition on June 8, 1994 may have looked at the green card bulletin and thought his Filipino sibling would have to wait “only” 17 years. In fact, he had to wait 23.

How green card time moves backwards

To know when an immigrant entering the process today will receive a visa, the government would need to know the number of petitions filed in each year under each green card category, the nationality of the beneficiary of each petition, and the nationalities of any spouses and children of the petition beneficiary.

A precise estimate is impossible because some applicants abandon their petitions, apply sometime after their priority date comes up, have additional children, get married, become ineligible, etc. But one would think that the government would attempt to track the basic information carefully, so it could give at least a decent estimate of the future wait times. But being the government, it naturally doesn’t, so whenever the State Department moves up the “priority date,” it essentially guesses how many people more will apply. If the State Department guesses wrong, it realizes its mistake and moves the priority date back in time. In other words, green card waiting time doesn’t move linearly like real time does. It stops, starts, and even runs in reverse. The government calls movement backward a “retrogression.”

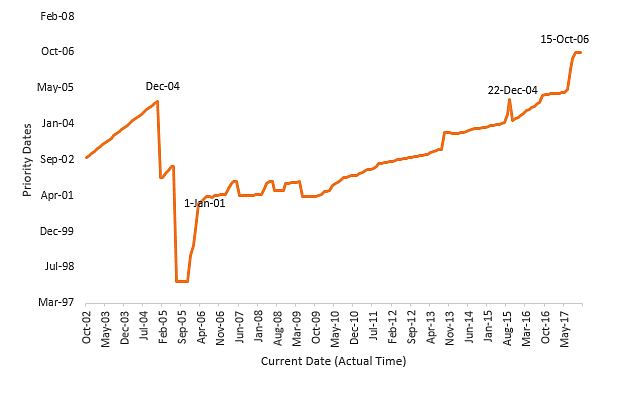

Figure 1 below highlights how priority dates move in the green card backlog for Indian college graduates sponsored by U.S. employers under the employment-based third preference category. When priority dates move ahead in time, the orange line goes up. When they move back in time, it goes down. When the priority date is the same as the current date for multiple months, it goes in a straight line at about a 45-degree angle, progressing steadily upward with each month. As Figure 1 shows, from October 2002 through December 2004, priority dates were current.

Immigrants who were the beneficiary of a green card in December 2004 would have thought, if they had looked only at the priority date, that they would receive their visa almost immediately. In fact, they had to wait more than a decade—until September 2015 to apply. Then, when they finally did apply, the priority immediately retrogressed again. When this happens, the government sets their applications aside until the date becomes current again. Since December 2004, there have been seven significant retrogressions and several other smaller ones.

Figure 1

Priority Dates for Employment-Based (EB‑3) Immigrants from India, October 2002 to November 2017

Source: U.S. Department of State

The big retrogression in 2005—when the priority date moved back to 1998—isn’t quite as meaningful as it appears. The State Department moved the dates back that far just to prevent anyone from applying. It’s not that the wait really grew quite that much. (If you want to know why the big jump happened, skip to this endnote.[1]) In any case, starting from March 2006—right after the big dip where Figure 1 shows “1‑Jan-01”—green card time moved about half as fast as actual time. Priority dates have advanced five years and ten months, while actual time moved forward 11 years in eight months. Figure 2 shows the wait for Indian immigrants to apply more than doubled from 5 years to 11 years, while waits for all other immigrants (excluding China, Philippines, and Mexico) have disappeared.

Figure 2

How Long Applicants Had to Wait to Apply for Green Cards from India and Elsewhere*, October 2002 to November 2017

Source: U.S. Department of State

*Excluding China, Philippines, and Mexico

Wait times are actually longer than Figure 2 shows. Figure 2 only shows the wait to apply, not to receive an approval. As I mentioned before, when the State Department moves the dates forward, and more applicants apply than there are slots available, their applications are held in abeyance until numbers are available again. This post-application waiting period still happens today. In fact, nearly 140,000 immigrants are waiting at this stage in the employment-based categories, and more than a third of them are Indians. It will take several years to clear just these cases from the backlog.

So how long will Indian immigrant workers have to wait going forward? Again, no one really knows for certain. In 2012, Stuart Anderson of the National Foundation for American Policy estimated 70 years. In 2014, the government estimated that 234,000 high skilled workers were waiting to apply for green cards. The family of the workers, however, use up a little more than half of the green card quotas, so there are probably now roughly half a million green card holders in line.

For the two employment-based categories with the longest waits, Indians can only receive 5,600 green cards (out of 80,000). We would need to know what share of those in line are Indian and what share are waiting in which of the employment-based categories to provide a good estimate of the wait for immigrants applying today. This information isn’t available. But if even half of these workers are Indians in the EB‑3 category—which seems very likely given how much longer Indians in this category have already been waiting than other nationalities—then their wait would be about a century.

In other words, it’s possible that almost all of the Indian workers applying today will die before they receive permanent residency, while other immigrant workers will receive their green cards almost right away. This is the system that Congress refuses to reform.

[1] Two factors apparently combined to slam the brakes on Indian workers—and everyone else in the EB‑3 green card category—in 2005. First, Congress passed a law at the start of FY 2001 that eliminated the backlog temporarily in 2003 and 2004. The law waived the per-country limits in situations where the worldwide limit for the category otherwise would not be filled, and it temporarily increased the number of green cards by recapturing visas that went unused in 1999 and 2000 (unused visas are a crazy topic for another post).

At the very same time, Congress created a new agency—U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS)—to adjudicate green card applications from temporary workers in the United States, and it was developing new procedures to adjudicate applications. Even though the State Department kept telling immigrants that they could apply, USCIS wasn’t processing them quickly enough. This led to a growing backlog in green card applications. Once USCIS instituted measures to catch up, the State Department realized that it let far too many applicants apply and slammed on the brakes. These applications are then held in abeyance.