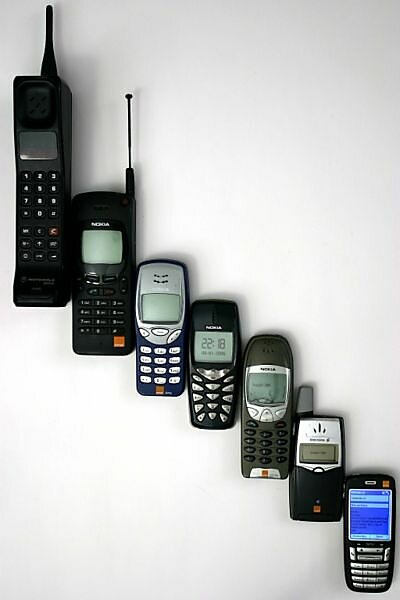

When I was a kid in the 1960s and we came back from a visit to my grandmother’s, my mother used to call my grandmother, let the phone ring twice, and then hang up. It was important for my grandmother to know that we’d arrived home safely, but long-distance telephone calls were too expensive to indulge in unnecessarily. When I entered Vanderbilt University in 1971, my parents had to decide whether to pay for a telephone in my dorm room. They decided to do so, but most of the thoroughly upper-middle-class students on my floor did not have phones. Phones cost real money back then. Then came the breakup of the AT&T monopoly in 1984. Phone technology and competitive service provision exploded. In 1982, Motorola produced the first portable mobile phone. It weighed about 2 pounds and cost $3995. Within a very few years they were much smaller, much cheaper, and selling like hotcakes.

Today there are some 4.6 billion mobile phones in the world, and counting, or about 67 per every 100 people in the world. The newer ones allow you to carry in your hand more computing power than the computers that put Apollo 11 on the moon. You can cruise the internet, find your location with GPS, read books, send texts, pay bills, process credit cards, watch video, record video, stream video to the web, take and send photos — oh, and make phone calls from just about anywhere. Unimaginable just a few years ago.

And to celebrate this incredible achievement, Slate and the New America Foundation are holding a forum titled “Can You Hear Me Now? Why Your Cell Phone is So Terrible.”

This is an old story. Markets, property rights, and the rule of law provide a framework in which technology and prosperity soar, and some people can only complain. I was reading some of Deirdre McCloskey’s forthcoming book Bourgeois Dignity this week. She points out that the average person lived on the equivalent of $3 a day in 1800. Today there are six and a half times as many people, but the average person earns and consumes 10 times as much, far more than that in the most capitalist countries. And yet some people, most leftist intellectuals, continue to ignore what McCloskey calls “the gigantic gains from bourgeois dignity and liberty” and to denounce the markets, economic liberalization, and globalization that have liberated billions of people from eons of back-breaking labor.

Now don’t get me wrong. I’m a big fan of consumer reporting and analysis, which is an important part of a robust marketplace. Competition and consumer reporting both help to keep prices low and quality improving. And there’s plenty of room for criticism of cell phone pricing, contracting, and service. But when a discussion like this is held by a public policy research organization and a public-affairs magazine as part of a program on public policy, then it’s not just consumer advice. It is presumably a discussion of what the sluggish, coercive institution of government can do to improve — or more likely impede — a fabulously dynamic, constantly improving consumer-directed industry. And that usually ends in tears.

Maybe we should hold a forum titled “Can You Hear Me Now? And Watch Me on Video? And Read My Book on Your Handheld Device? And Check Your Blood Pressure and Glucose? How Markets, Innovation, and Entrepreneurs Have Taken Cell Phone Technology from Clunker to Computer in Barely a Generation.”