The arrest on Saturday of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, leader of the Sinaloa Cartel, is no small feat. He was perhaps the world’s most wanted man, and his capture certainly represents a major political victory for Mexico and its president Enrique Peña Nieto. But just like the killing of Pablo Escobar in 1993 didn’t end the war on drugs, the downfall of Joaquín Guzmán won’t put an end to drug trafficking in the Americas.

As leader of Mexico’s largest criminal organization, “Chapo” was the central figure in the breakout of drug violence in that country. In 1992, Guzmán decided to invade the turf of the Arellano Félix brothers in Tijuana. Years later he also declared war on the Juárez and Gulf cartels, thus unleashing years of unprecedented bloodshed in northern Mexico. Eventually he would succeed in controlling most of the lucrative routes, and his organization would become responsible for nearly half of all illegal drugs coming into the United States.

His power relied not solely on plomo (lead) but also plata (money). Some years ago, high-ranking officials at Mexico’s Attorney General’s Office were arrested for receiving bribes from the Sinaloa cartel. The sums were staggering: between $150,000 and $450,000 per month. Guzmán’s organization was also actively engaged in buying the support of policemen. According to the Secretariat of Public Security, every year the cartels spend approximately $1.2 billion dollars bribing 165,000 cops all over Mexico (just as a comparison, the Merida Initiative, Washington’s aid package to Mexico and Central America to fight organized crime, totals $1.6 billion).

Without a doubt, Guzmán’s capture is a huge success for Enrique Peña Nieto. In the last seven months, the leaders of Mexico’s top three drug cartels (Zetas, Gulf and Sinaloa) were arrested without a single shot being fired. So, are we on the verge of wining the war on drugs? That all depends on what the ultimate goal is. Is it taking down drug kingpins or stopping the flow of drugs into the United States? If it’s the latter, the war is far from over. A report from the Office of Intelligence and Operations Coordination of the U.S. Custom and Border Protection agency looked at drug seizure data from January 2009 to January 2010 and matched it with the arrests or deaths of drug operatives (11 druglords in total). It found that “there is no perceptible pattern that correlates either a decrease or increase in drug seizures due to the removal of key DTO [drug trafficking organization] personnel.”

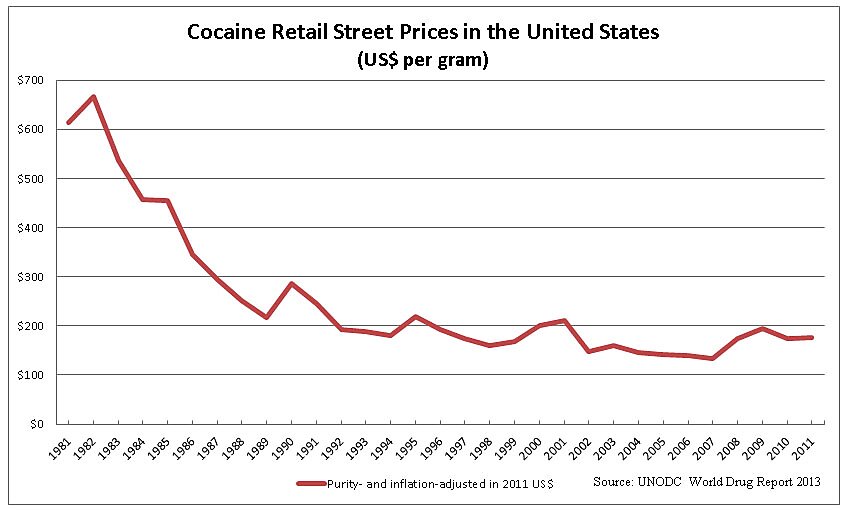

The latest National Drug Threat Assessment report from the Justice Department indicates that while cocaine availability has been declining since 2007, that of marijuana, heroine and methamphetamine is on the rise. In the case of cocaine, the fall in availability hasn’t produced a sharp increase in its street price, as the graph below shows:

We shouldn’t expect a major decline in the flow of drugs into the United States, just as such didn’t occur after Pablo Escobar, then the leader of the powerful Medellín cartel, was killed in December 1993.

The consequences on the dynamics of violence in Mexico are yet to be seen. Sinaloa is the last major drug organization with a semi-pyramidal structure in that country, and it’s also the most professionally run. Two of “Chapo’s” top lieutenants, Juan José “El Azul” Esparragosa and Israel “El Mayo” Zambada remain at large. It’s likely that they already had in place a succession plan in case Guzmán was arrested. Some experts even speculate on a new generation of drug kingpins taking over Sinaloa. So it isn’t sure that the cartel will implode or disintegrate. Nor we should expect an outbreak of violence as other cartels try to move into Sinaloa territory. That didn’t happen when Miguel Ángel Treviño, leader of the Zetas, was arrested last July.

The arrest of “Chapo” Guzmán is being seen as a major triumph in the battle against organized crime in Mexico. But his capture doesn’t bring us any closer to victory in the war on drugs.