“… equally efficacious, and equally a hoax.” – Benjamin Disraeli, 1848[1]

One of the highlights of the U.S. summer for Fed watchers is the annual ritual in which the Fed’s economic soothsayers peer into their crystal balls, a.k.a. their stress tests, to reassure us that the U.S. banking system is robust and getting stronger all the time.

You see, while the future is uncertain, the results of the stress tests are not. Praise be that the news is always good and getting better.

This year, the news is particularly good. As usual, the key capital metrics across the system are better than ever. And whereas in previous years there were always dunces who failed, the latest set of stress tests are the first in which all the banks passed and this year’s class laggard, Capital One, got only the mildest of slaps on the wrist.

As James Ferguson of The MacroStrategy Partnership notes in a recent commentary on the latest stress tests:

… everywhere you look, the Fed now seems to be bending the rules in the banks’ favour. … This [stress test] appears to be a test that has been designed to be passed.”[2]

In fact, the Fed is so pleased with the performance of its stress-test examinees that it decided to reward them (or, more precisely, their shareholders) with a big dividend/buyback party that will give them a big windfall.[3] The Fed provides the punchbowl which will be paid for by other bank stakeholders including taxpayers — yes, the same taxpayers who are still being compelled to subsidize the banks (via Too Big to Fail, deposit insurance, and such like) to take excessive risks and overleverage themselves, and who stand to pay the bill if there is another crisis and the banks get bailed out again.[4]

It is curious that these capital distributions are being welcomed by many of the same people who have argued vociferously against higher capital requirements. Advocates of low capital requirements say that high capital requirements would limit banks’ lending capacity, but they fail to note that this is what dividend payouts do too.

Nor is there any sign that the Fed is inclined to take away the punchbowl any time soon. Former Fed chairman William McChesney Martin must be turning in his grave.

Indeed, plans are afoot to make future stress tests even less demanding: the days when banks felt challenged by the Fed’s stress tests are well and truly over.

So this year’s stress tests are great news for bank shareholders, but bad news for everyone else.

Headline results

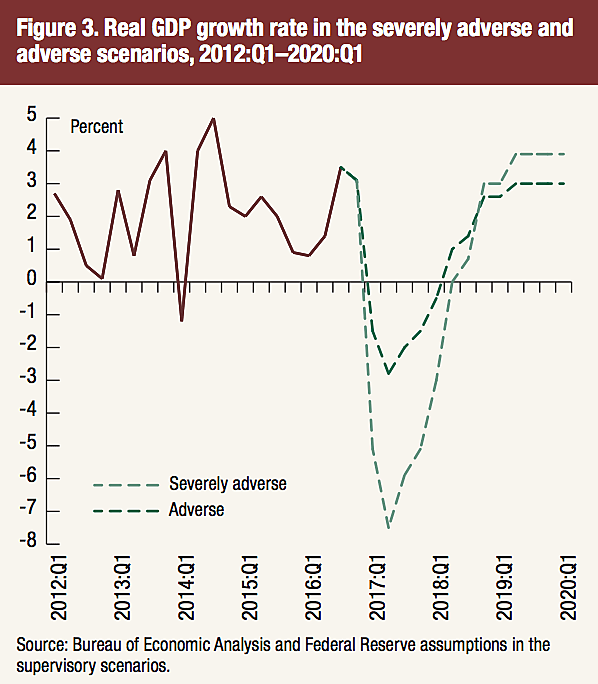

The results for the Fed’s stress tests were published in two stages. The results of the first stage – formally known as the Dodd-Frank Act Stress Tests (DFAST) 2017 — were published on June 22. These tests give results showing how the banks involved would fare under an “adverse scenario” and a “severely adverse scenario” projected over the period 2017:Q1 to 2019:Q1. The 34 bank holding companies (BHCs) tested — generally those with $50 billion or more in total consolidated assets — represent more than 75 percent of the assets of all domestic BHCs.

These scenarios project the steep decline in real U.S. GDP shown in Figure 3 of the report.

The “severe adverse scenario” suggests a shock (in real GDP terms) that is more severe than the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). It also posits the U.S. unemployment rate rising by approximately 5.25 percentage points to 10 percent, accompanied by heightened stress in corporate loan markets and commercial real estate. Equity prices fall by 50 percent through the end of 2017, accompanied by a surge in equity market volatility, which approaches the levels attained in 2008. House prices and commercial real estate prices also experience large declines, with house prices and commercial real estate prices falling by 25 percent and 35 percent, respectively, through the first quarter of 2019. Total projected losses across the 34 banks come out to $493 billion.

The results for the second stage — the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) 2017 — were published on June 28. The CCAR provides a quantitative assessment of a firm’s capital adequacy and planned capital distributions (or “capital plan”), such as any dividend payments and stock buybacks, and provides a qualitative assessment of the bigger and/or more complex firms. The principal difference between the DFAST and CCAR stress tests is that the former uses a standardized capital plan mandated by the Dodd-Frank Act, whereas the CCAR uses a firm’s planned capital actions under its BHC baseline scenario.

The significant point about this year’s CCAR was that the Fed proved to be in a remarkably generous mood: it approved the capital plans of 33 out of the 34 banks in the stress test exercise. The one exception, Capital One, was given a conditional non-objection to its capital plan, conditional on its plan making certain improvements by the end of the year.

“This year’s results show that, even during a severe recession, our large banks would remain well capitalized,” said the official in charge of the stress tests, Governor Jerome H. Powell, on June 22. “This would allow them to lend throughout the economic cycle, and support households and businesses when times are tough.”

I disagree.

Generic Weaknesses of the Stress Tests

My doubts start with the observation that the primary purpose of the stress tests program is to reassure the public that the banking system is safe. So when the Fed says the U.S. banking system is in good shape, well, they would say that, wouldn’t they? That is what central banks always say and they can realistically do no other. The stress tests are not some independent assessment of the financial strength of the banking system carried out by experts who are free to arrive at conclusions that might not suit the Fed; instead, the stress tests are part of a publicity campaign by a public agency with is own interests and agenda. Therefore, the credibility of the exercise is compromised before it has even started.

A second problem is that the stress tests place far too much emphasis on a single scenario, its “severe adverse scenario.” Recall that stress tests originated as tools for financial risk management in the private sector, and the financial risk management literature recommends against stress tests that rely on a single stress event. The reason is obvious: a firm will face a range of risk scenarios, and if its risk managers assess its vulnerability to only one of these, then their stress tests cannot give them any reassurance that it will be safe in the event of any major stress scenarios that it did not consider.

The same should apply to stress tests carried out by a central bank. Now admittedly, the Fed’s “severe adverse stress scenario” is, indeed, a severe one. However, it is still only one scenario (if one ignores the pointless “adverse scenario”), and there are other scenarios that could have a significant adverse impact on the U.S. banking system or economy more generally.[5] Examples would be a collapse in the Chinese or eurozone banking systems, a major trade war, or a major shock in the oil market. Do the Fed’s stress tests give us any assurance that the U.S. banking system could withstand such shocks and still be in good shape? No. And why not? Because the Fed’s stress tests did not even consider them.

Turning now to the modeling itself, it seems to me that the stress test projections fail a basic reality check: the Fed’s projected losses seem to be low. First, the projected loss of $493 billion from a scenario that in GDP growth or unemployment rate terms is about as severe as the GFC is barely half the losses accumulated so far since the GFC.[6]

More tellingly, Table 2 on p. 25 of the 2017 DFAST Report indicates that the stressed portfolio loan-loss rate is 5.8 percent. This is a very low loss rate for a major stress. Loan-loss rates in crises can easily be double that (e.g., the loan-loss rate in the United States in the period since the GFC is over 12 percent[7]) and sometimes even higher. These low projected loss rates suggest that the link between the severe adverse scenario and projected losses is too low to be plausible.

The modeling of the Fed’s stress scenarios over the years has been subject to a number of other major problems, some of which are set out in Morris Goldstein’s new book, Banking’s Final Exam.[8] The modeling is much too orderly to capture key features of real-world financial crises. It understates the fat tails and nonlinearities, does not capture the amplification effects, and ignores the chaos, confusion, contagion, funding and firesale problems involved.

In addition to underestimating the impact of real-sector effects on the financial sector, it also underestimates the impact of financial-sector effects on the real sector. These factors make financial crises much more costly than normal recessions and the stress tests greatly understate them. Goldstein also provides a neat example that shows the near-impossibility of getting empirically plausible models of real-world financial crises:

(a) Note that when former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke testified to Congress in 2007 about the subprime crisis, he estimated that it would generate total losses in the neighborhood of $50 billion to $100 billion … (b) But … when Bernanke gave testimony in an AIG court case … he explained that, by September and October of 2008, 12 of 13 of the most important financial institutions in the United States were at risk of failure within a period of a week or two. The question for stress test architects and modelmakers is, How do you make your models generate a transition from (a) to (b) in the course of, say, a year or two? This is not a technical sideshow. In stress modeling, it is the main event [emphasis added].[9]

I would also note several other problems with the Fed’s modeling. First, the Fed’s own history suggests that the Fed itself is a major risk to the banking system, e.g., through its own erratic monetary policy, and yet the Fed’s stress tests take no account of Fed risk. Second, the Fed’s prudential policies, including the stress tests, have the effect of standardizing banks’ risk management practices, thereby exposing the whole system to the weaknesses in the Fed’s own risk management models and creating the potential for hidden systemic risks to which the Fed’s and the banks’ risk models are blind.[10]

There is also a sense in which the stress tests are aiming to achieve the impossible. Frank Partnoy and Jesse Eissinger have made the compelling case that it is no longer possible even for a qualified expert to infer a bank’s true financial state from its audited accounts. But in that case one has to wonder how anyone – the Fed included – can possibly work out a bank’s financial condition from exercises such as the stress tests. It strains credibility to suggest that some questionable spreadsheet model of an arbitrary hypothetical shock can be relied upon to compensate for a major weakness in a bank’s accounts. If a bank has a large hidden (e.g., off-balance-sheet) loss that does not show up on its accounts, then how can we expect a stress test to identify that hidden loss? The answer is that we can’t. If the accounting numbers are not right, then the stress tests cannot correct for them.

Biggest Problems with the 2017 Stress Tests: Low Capital Standards and Regulatory Capture

My biggest concerns with the 2017 stress tests, however, relate to the low pass standards and to the evidence that the longstanding tug of war between the banks and the Fed over the stress tests has finally ended with the victory of the banks over the Fed.

Take the headline capital adequacy metric, the CET1 (Common Equity Tier 1) ratio —that is, the ratio of CET1 capital to Risk-Weighted Assets (RWA). I would immediately dismiss these numbers because the RWA metric is unreliable to the point of being discredited.[11]

The more reliable capital ratio metric is the leverage ratio, defined as the ratio of core capital to some measure of total exposure such as un-risk-weighed assets.

In its 2017 stress tests, the Fed uses two different leverage measures each with its own pass standard: the plain “leverage ratio,” defined as the ratio of Tier 1 capital to average assets, with a pass standard of 4 percent; and a newly introduced and more demanding “supplementary leverage ratio” with the same numerator but an expanded denominator equal to average assets plus (some) off-balance-sheet exposures, and which has a pass standard of 3 percent. These pass standards are not high, however. I find it difficult to believe that a banking system with leverage ratios close to these pass standards would be robust and able to service the real economy as we would wish it to in a subsequent stress scenario—especially bearing in mind the unreliability and gameability of the regulatory and accounting numbers, the off-balance-sheet risks that are not captured in those numbers, and the enormous scope for errors in the stress test modeling.

Moreover, both leverage ratios use Tier 1 capital in the numerator, but Tier 1 is an unreliable capital measure because it includes hybrid securities that are unreliable as core capital in a crisis.[12]

Then there is the question of what the ideal minimum required leverage ratio should be. To start with, many economists have called for higher capital requirements and/or criticized inadequate regulatory capital standards as a contributory factor to the severity of the GFC. These include: James Barth and Matteo Miller, Sheila Bair, Charles Calomiris, James Grant, Thomas M. Hoenig, Simon Johnson, Ed Kane, Norbert Michel, Gerald P. O’Driscoll, Jr.[13], The Systemic Risk Council and Sir John Vickers. In his book, The End of Alchemy, former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King wrote that a “minimum ratio of equity to total assets of 10 per cent would be a good start.”[14] Others would suggest higher minimum ratios. A famous example is an important letter drafted by Anat Admati in the Financial Times in 2010, in which no less than 20 renowned experts recommended a minimum ratio of equity to total assets of at least 15 percent. Independently, Morris Goldstein has recommended a leverage ratio of around 15 percent, John Allison, Martin Hutchinson and yours truly have called for minimum capital to asset ratios of at least 15 percent, and Allan Meltzer[15] and Walker Todd[16] have recommended a minimum of 20 percent for the largest banks.

The pass standards in the stress tests (and those in the leverage ratio tests in particular) are far from being an academic issue. Had the latter been higher, then some or all of the banks would have failed to meet the minimum capital requirements and the Fed would have been obliged to object to their capital plans — in other words, the banks would have been required to further build up their capital.

This issue is particularly acute for the 8 big systemic banks. The following table shows their DFAST and CCAR supplementary leverage ratios under the severe adverse scenario:

Table: Minimum Stressed Supplementary Leverage Ratios for U.S. Systemic Banks (Percent)

| Bank | DFAST | CCAR |

| Bank of America | 5.4 | 4.3 |

| Bank of New York Mellon | 5.5 | 4.8 |

| Citigroup | 5.5 | 4.5 |

| Goldman Sachs | 4.1 | 3.1 |

| JP Morgan Chase | 5.0 | 3.9 |

| Morgan Stanley | 3.8 | 3.2 |

| State Street | 4.2 | 3.6 |

| Wells Fargo | 6.1 | 5.3 |

| Weighted average | 5.4 | 4.4 |

Note: The pass standard is 3 percent. Numbers based on Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Dodd-Frank Act Stress Test 2017: Supervisory Stress Test Methodology and Results, Tables 2 and 4; and Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review 2017: Assessment Framework and Results, Tables 1 and 6.A. Both reports were published in June 2017.

Several points jump out.

First, the stressed supplementary leverage ratios in the DFAST column are low even before the bank-specific distributions in the CCAR column. Had the Fed applied a higher minimum pass standard for CCAR plans then most if not all of the banks’ capital plans would have been rejected: at a 4 percent minimum, the capital plans of only four banks (BOA, NY Mellon, Citi and Wells Fargo) would have been approved; at a 5 percent minimum, only Wells Fargo’s plan would have been approved; and at a 6 percent minimum none of the big banks’ capital plans would have been approved.

In this context, it is interesting to note that the Fed is in the process of imposing a 5 percent minimum “enhanced supplementary leverage ratio” on the 8 big systemic BHCs, and a 6 percent minimum on their federally insured subsidiaries, to become effective on January 1, 2018. One must wonder then why the Fed chose to impose a 3 percent supplementary leverage ratio on them in the 2017 stress tests. As a general rule, the pass standards in any central bank stress tests should be at least the minimum required standards under the capital adequacy rules, otherwise banks can be (and in the case of the 2017 CCAR seemingly were) deemed to have passed the stress tests even though their stressed leverage ratios appear to fall below the regulatory minima.

Second, the difference between the two columns — the distributions approved by the CCAR vs. those assumed in the DFAST — are remarkably high, with most of them being at least 100 basis points. Not reported in the table are the banks’ plans to increase their payout ratios — their ratios of distributions to net earnings — to nearly 100 percent on average, with some banks planning even higher payout ratios. For the Fed to approve distributions on such a scale, when the big systemic banks have such low leverage ratios and are being subsidized to run down their capital and take excessive risks too, seems reckless in the extreme.

Goldman Sachs gamed the system to near perfection: with a CCAR supplementary leverage ratio of 3.1 percent, it managed to persuade the Fed to approve a capital plan that left it with 10 basis points to spare over the Fed’s regulatory minimum. We can now presumably expect that in future CCARs, the banks’ stressed supplementary leverage ratios will converge to the minimum possible, 3 percent.

Why is the Fed approving such generous distributions when the banks’ leverage ratios are so low? Two words: regulatory capture.

Or consider the following live blog feed from MarketWatch on the Fed’s press conference on June 28th announcing the results of the CCAR:

4:30 pm EDT

One thing that has emerged from the stress tests is that banks are running very close to the minimum thresholds on capital and leverage. A Fed official didn’t deny that. That means the banks are getting good at calculating the maximum payouts they can make to investors without failing the stress tests.

4:30 pm EDT

A Federal Reserve official said banks have substantially increased their payouts, as they’ll be paying out close to 100% of projected net income over the coming four quarters, compared to 65% last year. The Fed sees that as a sign of health. “I’m pleased that the CCAR process has motivated all of the largest banks to achieve healthy capital levels and most to substantially improve their capital planning processes,” said [Governor] Powell in a prepared statement.”

I hope that I am not the only one to sense a disconnect here.

Is the U.S. Banking System Really in Good Shape?

So the Fed is confident that the U.S. banking system is in good shape – and, so much so, that on June 25 this year, Chair Yellen said that she did not expect to see another financial crisis in her lifetime. Let’s wish her a long life and hope that her prediction does not go the way of Keynes’s “We will not have any more crashes in our time” (1926) or Irving Fisher’s “Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau” twelve days before the October ’29 crash.[17] But still the doubts creep in. For a start, she has often gotten her forecasts wrong before, even with a large staff of economists from top schools grinding them out. Consider this little beauty from January 22, 2007:

While the decline in housing activity has been significant and will probably continue for a while longer, I think the concerns we used to hear about the possibility of a devastating collapse—one that might be big enough to cause a recession in the U.S. economy—have been largely allayed.

History suggests that crises always recur and that each crisis always catches the central bank off-guard. “This time is different,” they always say, but it never is.

We should be concerned at the obvious blindspots in the Fed’s stress tests: the scenarios not considered, the low pass standards, the danger of hidden systemic risks, and the worry that the stress tests have now become an easy-to-pass compliance ritual that provides little useful information about the true state of the banks. One cannot dismiss the possibility that the good performance of U.S. banks in the latest stress tests merely indicates that banks have mastered the now routine annual stress test game. They have had plenty of practice.

We should also be concerned about how the Fed is going to achieve monetary normalization without inadvertently bursting the “everything bubble” that it has blown so lovingly since 2008. Elementary back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that losses from a collapse in asset prices could run into trillions, i.e., multiples of the $493 billion losses in the Fed’s “severely adverse scenario” which point also suggests that the Fed’s projected losses might be well on the low side.[18] Even a natural optimist like Robert Shiller is now warning that his CAPE index is higher than at any time since 2000, the eve of the dotcom crash, and 1929.

The Fed may regard the U.S. banking system as well nigh unsinkable but the Fed’s capital adequacy metrics and stress test pass standards on which this view is based are clearly inadequate. The U.S. banking system is also sailing in iceberg-infested waters and one worries that the Fed’s stress test radar system does not detect even those icebergs that are in plain view.

______________

I thank Anat Admati, Jim Dorn, James Ferguson, Morris Goldstein, Martin Hutchinson, Gordon Kerr, Jerry O’Driscoll, Sir John Vickers and Basil Zafiriou for helpful feedback.

[1] M. Hutchinson, “St Januarius’ blood,” The Bear’s Lair, January 6th 2010.

[2] J. Ferguson, “Annual Fed Stress Test: Turning the dividend ATM on full,” The MacroStrategy Partnership, June 26th 2017, p. 2.

[3] As an aside, one has to ask why share repurchases by deposit-insured banks are even legal? Given bankers’ incentive to game the system by running their capital down to the lowest possible level, share repurchases are highly undesirable because they give bankers an additional and easy-to-implement means of decapitalizing their own banks. Buybacks also destabilize the banking system by making it more pro-cyclical. Banks will repurchase shares at the top, and do emergency issues or lobby for bailouts at the bottom, thereby also helping to destroy their shareholders’ wealth and inflict losses on taxpayers as well. Share buybacks may be justifiable for a company under laissez-faire conditions, but when banks are incentivized to take excessive risk and run down their capital, they become a self-dealing handout to stock-optioned management that undermines the stability of the banking system.

[4] The definitive reference on this issue is A. Admati and M. Hellwig, The Bankers’ New Clothes: What’s Wrong with Banking and What to Do about It, Princeton University Press, 2013. See also L. Gambacorta and H. S. Shin “Why bank capital matters for monetary policy,” BIS Working Papers No. 558, April 2016.

[5] The Fed also applied a global market shock to the trading portfolios of six BHCs with large trading and private equity exposures, and it applied a counterparty default component, which assumes the default of a BHC’s largest counterparty under the global market shock, to the same six BHCs and two other BHCs with substantial trading, processing, or custodial operations. However, these components are add-ons to the economic conditions and financial market environment specified in the adverse and severely adverse scenarios, and the former is merely a watered-down version of the latter. So in essence, the stress tests are still dependent on one key scenario, the severe adverse one.

[6] Ferguson, op. cit., p. 5 estimates that the cumulative loss inflicted on U.S. banks by the GFC was as much as $880 billion, excluding fines. I suppose a defender of the stress tests might argue that the Fed’s projected losses are so low because of the relatively short horizon assumed in the stress test, but this is hardly an adequate defense: the logical implication of this position is that the Fed should use a longer horizon. Remember that many of the losses associated with the GFC took much longer than 2 years to feed through into publicly disclosed realized losses.

[7] Ferguson, loc. cit. estimates that U.S. banks’ loss rate was equivalent to 12.4 percent of peak 2008:Q3 loans of $7.1 trillion.

[8] M. Goldstein, Banking’s Final Exam: Stress Testing and Bank-Capital Reform. Washington DC: Petersen Institute for International Economics, May 2017. See also here and here.

[9] Goldstein, op. cit., p. 251.

[10] Indeed, concerns about the stress test program have recently been voiced by the GAO and even by the Fed itself.

[11] See, e.g., here, here or here.

[12] Sir John Vickers, “Response to the Treasury Select Committee’s Capital Inquiry: Recovery and Resolution,” March 3rd 2017.

[13] Gerald P. O’Driscoll, Jr., “The Financial Crisis: Causes and Consequences.” The Intercollegiate Review (Fall 2009): 4–12.

[14] Mervyn King, The End of Alchemy: Money, Banking and the Future of the Global Economy, London: Little, Brown, 2016, p. 280.

[15] Cited in A. Admati and M. Hellwig, op. cit., p. 311.

[16] “Start with 20 percent on a leverage basis, not risk adjusted, for the big boys, and then we’ll talk.” Personal correspondence, May 21st 2017.

[17] New York Times, October 17th 1929.

[18] See, e.g. K. Dowd and M. Hutchinson, “From Excess Stimulus to Monetary Mayhem,” Cato Journal Vol. 37, Number 2, Spring/Summer 2017, p. 316, note 16.