Dear Chair Hill, Ranking Member Waters, and Members of the Committee,

After fifty-five years of financial surveillance steadily increasing, it is time to take steps to rein in the Bank Secrecy Act.1 Adjusting the thresholds for financial surveillance would mark a substantial improvement for Americans’ financial privacy, banks’ ability to serve customers, and law enforcement’s ability to catch criminals.

In 1970, the American Bankers Association warned Congress that the Bank Secrecy Act posed a threat to the civil liberties of customers and the efficiency of the market.2 Clifford Sommer, president of the association at the time, testified that “Banks have an obligation to their customers to maintain the privacy of their personal financial affairs except in response to subpoena or other regular legal process.” He went on to warn that the Bank Secrecy Act would create a sweeping system of financial surveillance that would violate this privacy.

Sommer also warned that the bill risked creating “an unnecessarily elaborate system of records and reports which banks … would be required to file and maintain without regard to whether such records are needed.”

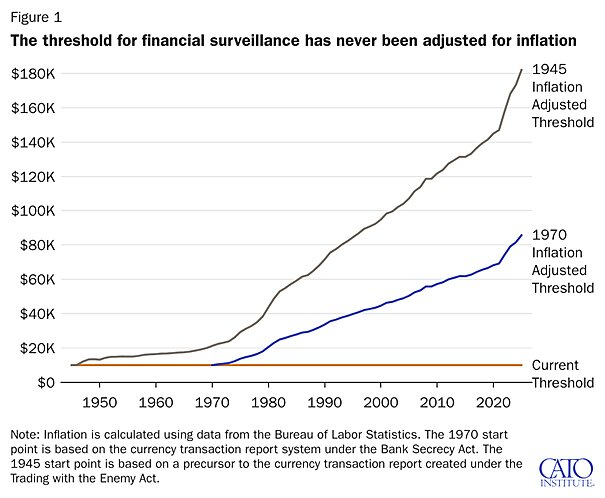

It’s been fifty-five years since Sommer warned Congress, and his concerns can be seen today. Because Congress passed the Bank Secrecy Act, and did so without safeguards, the level of surveillance has increased every year through inflation alone. What was $10,000 in 1970 is now around $86,000 (Figure 1). Put differently, you could buy two brand new Corvettes for $10,000 in 1970.3 Today, you could spend all of that on just the engine.4

The increasing level of surveillance is partly why the number of reports filed tends to increase each year. Banks filed 27.5 million reports in 2024.5 Of those reports, 20.5 million reports were for nothing more than large cash transactions.6 Banks spend an estimated $59 billion complying with this system.7

Yet, it is not just an issue of unjust surveillance and rising compliance costs. The unnecessarily low threshold also forces the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) to face an ever-expanding workload. In fact, that may be why, despite being asked for decades, FinCEN has no idea whether these reports are actually helping to catch criminals.8 As Representative Bryan Steil (R‑WI) once described it, “Finding a needle in the haystack is dependent on a number of things.”9 One of those factors is how much hay is in the stack. Every year that the number of reports is arbitrarily increased through inflation is another year that it is progressively more difficult to identify actual criminal activity.

Reforming this inefficient and ineffective system is long overdue. One of the foundations of this country is that people are innocent until proven guilty. Sweeping financial surveillance for nothing more than crossing an outdated threshold takes the opposite stance. Is the approach in the bill perfect? No.10 Would it be a positive step forward? Yes. The Financial Reporting Threshold Modernization Act may not address every problem with the Bank Secrecy Act regime, but financial surveillance has increased unchecked for far too long.11 Representative Loudermilk’s approach would mark the first step in finally changing the tide.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.