Chairman Paul, Ranking Member Peters, and Members of the Subcommittee — thank you for the opportunity to speak with you today about an important topic that should worry every American concerned about the state of civil liberties.

In Riley v. California the U.S. Supreme Court recognized that searches of cellphones implicate privacy concerns beyond those associated with searches of wallets, cigarette packs, and other everyday items.1 Writing the Riley majority opinion, Chief Justice Roberts stated that the government's claim that the search of a cellphone and the search of a wallet are "materially indistinguishable" is "like saying a ride on horseback is materially indistinguishable from a flight to the moon."2

Roberts was correct. Our cellphones and laptops contain troves of revealing information about our personal relationships, careers, religious affiliations, and hobbies. It's no exaggeration to say that unfettered access to a cellphone allows investigators to uncover details about almost every intimate communication and relationship associated with the owner of the cell phone.

Officials with access to cell phones can easily view photos, calendars, email accounts, social media postings, and other revealing data. Riley's holding, that police need a warrant to search phones belonging to arrested persons, recognizes the privacy interests American adults have in the content of cell phones.

Despite Riley, cell phones and other electronic devices enjoy reduced protections at the border and functional border equivalents, such as airports. This is thanks to the long-standing "border exception" to the Fourth Amendment.3 This exception was recognized at the founding, but was not formally recognized until 1977 in United States v. Ramsey.4 The exception and Customer and Border Protection's (CBP) search authorities have also been codified in law.5

The Supreme Court has yet to consider the constitutionality of warrantless searches of electronic devices at the border. However, Congress can extend the Riley standard to the border via legislation.6

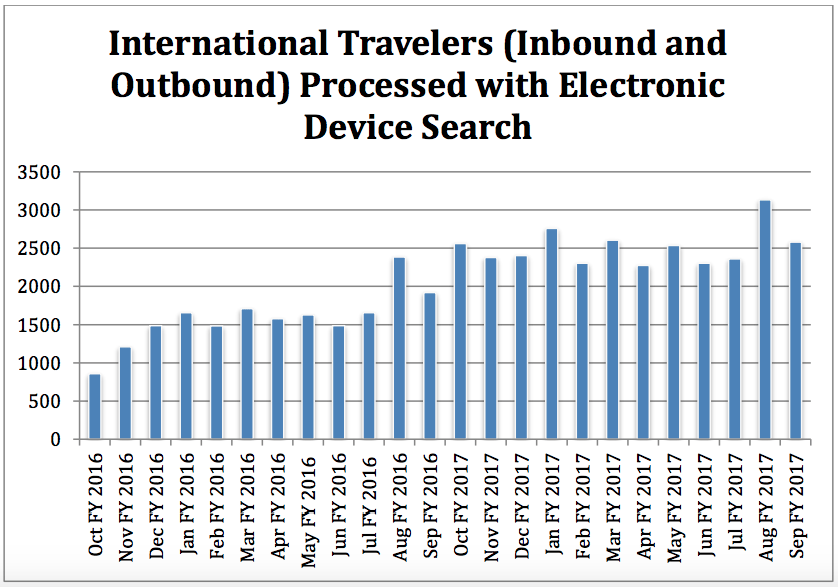

Although warrantless electronic searches affect a minority of travelers, the number of these searches has been increasing. According to CBP's figures, there was an almost 60 percent increase in the number of international travelers processed with an electronic device search between FY 2016 and FY 2017 (See Appendix A).7

A 2009 CBP directive on electronic device searches stated, "In the course of a border search, with or without individualized suspicion, an Officer may examine electronic devices and may review and analyze the information encountered at the border."8

In the wake of widespread concern about warrantless searches of electronic devices at airports CBP issued an updated directive earlier this year.9

The 2018 directive improved the 2009 directive, but not enough. The latest directive distinguishes between "Basic" and "Advanced" searches. Under current DHS policy, a search of an electronic device that doesn't involve an officer connecting the device to external investigatory equipment is a Basic search. Basic searches do not require suspicion, which is required for Advanced searches.10 The new directive includes a worrying provision that allows officers to examine a phone with external equipment if there is a "national security concern."11 This is especially worrying because the directive notes that "the presence of an individual on a government-operated and government-vetted terrorist watch list" creates reasonable suspicion.12 Government watch lists don't only include terrorists. Officials have placed law-abiding American citizens on watch lists designed to prevent dangerous people from flying.13

The 2018 directive also requires travelers to unlock their phones.14 CBP officers have compelled American citizens to unlock and hand over their phones, even after being told that the phone contained sensitive data, including those from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.15

According to the latest directive, officers conducting a search must either have travelers disable network connectivity or disable the connection themselves by (for example) putting the device in airplane mode.16

These policies are of little reassurance to travelers. Even in airplane mode, cellphones contain revealing information. Text messages, emails, photos, browsing histories, videos, and calendars are still available to officers examining a cellphone in airplane mode. In addition, cellphones in airplane mode do not conceal apps that the cellphone owners may use. You hardly need to have a phone connected to a network to uncover information about someone who has downloaded the Muslim Pro, Coinbase, Tinder, or Diabetes and Blood Glucose Tracker apps.

Current DHS policy does not do enough to protect travelers' civil liberties. S.823, the "Protecting Data at the Border Act," sponsored by Senator Wyden (D-OR) and S.2462, "A Bill to Place Restrictions on Searches and Seizures of Electronic Devices at the Border," sponsored by Sen. Leahy (D-VT) would improve the status quo, but they are not without their own issues.17

A welcome provision of S.823 is its warrant requirement for advanced/forensic searches. Alternatively, the legislation permits officers to request travelers to allow access to digital contents through informed consent, overriding the warrant requirement. However, unlike S.2462, it does not require DHS to report the number of electronic devices searches that resulted in criminal charges.18

S.2462, would also improve the current situation by requiring that CBP officers have reasonable suspicion an individual is carrying contraband or is inadmissible before conducting a search that does not involve the entry of passwords or assistance from other electronic devices.19 Like S.823, this bill requires probable cause for an advanced/forensic search.20

Under current policy, these searches are justified on the basis that they help CBP in its mission to prevent and investigate terrorism and the trafficking and possession of child pornography.21 However, DHS has not published figures showing how many of the warrantless searches of electronic devices have contributed to terrorism or child pornography-related convictions. Such data would be welcome, as it would allow the public to better assess the efficiency of warrantless searches that endanger their privacy. Both S.823 and S.2462 would improve DHS transparency regarding these searches.

Some of the United States courts of appeals have considered questions concerning the standard of suspicion necessary for CBP to conduct forensic searches of electronic devices.22 As things stand, there is no consensus.23 Until the Supreme Court addresses this issue, lawmakers can provide CBP with requirements that go beyond the unsatisfying directive issued by DHS.

The question of warrantless searches of electronic device searches at the border is only one of the many civil liberty concerns associated with immigration enforcement. CBP is interested in using drones with facial recognition capability.24 In addition, DHS is using facial recognition technology at select American airports, despite Congress never explicitly authorizing the collection of American citizens' biometrics via facial recognition.25

Again, thank you for your attention to this important matter and for the opportunity to testify before you. I look forward to answering any questions you may have.

Appendix A: International Travelers (Inbound and Outbound) Processed with Electronic Device Search between October FY 2016 and September FY 201726

|

Oct FY 2016 |

857 |

|

Nov FY 2016 |

1208 |

|

Dec FY 2016 |

1486 |

|

Jan FY 2016 |

1656 |

|

Feb FY 2016 |

1484 |

|

Mar FY 2016 |

1709 |

|

Apr FY 2016 |

1578 |

|

May FY 2016 |

1626 |

|

Jun FY 2016 |

1487 |

|

Jul FY 2016 |

1656 |

|

Aug FY 2016 |

2385 |

|

Sep FY 2016 |

1919 |

|

Oct FY 2017 |

2561 |

|

Nov FY 2017 |

2379 |

|

Dec FY 2017 |

2404 |

|

Jan FY 2017 |

2760 |

|

Feb FY 2017 |

2303 |

|

Mar FY 2017 |

2605 |

|

Apr FY 2017 |

2275 |

|

May FY 2017 |

2537 |

|

Jun FY 2017 |

2304 |

|

Jul FY 2017 |

2359 |

|

Aug FY 2017 |

3133 |

|

Sep FY 2017 |

2580 |

Notes:

1 Riley v. California, 134 S. Ct. 2473, 2488 (2014). Pg. 17 of slip opinion. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/13pdf/13-132_8l9c.pdf

2 Ibid.

3 U.S. Const. amend. IV

"The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized."

4 "That searches made at the border, pursuant to the longstanding right of the sovereign to protect itself by stopping and examining persons and property crossing into this country, are reasonable simply by virtue of the fact that they occur at the border, should, by now, require no extended demonstration." J. Rehnquist, United States v. Ramsey, 431 U.S. 616 (1977)

5 See: 8 U.S.C. §§ 1225 1357 19 U.S.C. §§ 482 507 1461 1496 1581 1582 1589a 1595a

6 Two pieces of legislation already aim to do this:

U.S. Congress, Senate, Protecting Data at the Border Act, S 823, 115th Cong., introduced in Senate April 4th, 2017.

U.S. Congress, Senate, To Place Restrictions On Search and Seizures of Electronic Devices at the Border, S 2462, 115th Cong., introduced in Senate February 27, 2018.

7 CBP Releases Updated Border Search of Electronic Device Directive and FY17 Statistics, published by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, January 5, 2018. https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/national-media-release/cbp-releases-updated-border-search-electronic-device-directive-and

8 CBP Directive No. 3340-049 by Acting CBP Commissioner Jay Ahern, August 20, 2009. https://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/cbp_directive_3340-049.pdf

9 CBP Directive No. 3340-049A by Acting CBP Commissioner Kevin McAleenan, January 4, 2018. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/CBP%20Directive%203340-049A_Border-Search-of-Electronic-Media.pdf

10 CBP Directive No. 3340-049A Section 5.1.3 (pg.4)

11 Ibid. Section 5.1.4 (pg. 5)

12 Ibid.

13 Ramzi Kassem, "I Help Innocent People Get Off Terrorism Watch Lists. As a Gun Control Tool, They're Useless," The Washington Post, June 28, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2016/06/28/i-help-innocent-people-get-off-terror-watch-lists-as-a-gun-control-tool-theyre-useless/?utm_term=.844f3c4719cc

14 "Travelers are obligated to present electronic devices and the information contained therein in a condition that allows inspection of the device and its contents. If presented with an electronic device containing information that is protected by a passcode or encryption or other security mechanism, an Officer may request the individual's assistance in presenting the electronic device and the information contained therein in a condition that allows inspection of the device and its contents."

Ibid. Section 5.3.1 (pg.6)

15 "But the agent never touched Bikkannavar's bag — instead, he asked for his smartphone. Bikkannavar handed it over, assuming the agent might just want to inspect it to make sure it wasn't something more dangerous in disguise. The agent turned it over in his hand and asked for the passcode.

Bikkannavar was taken aback. The phone was Jet Propulsion Lab property, he explained, pointing out the barcode stuck to the back. It was his duty to protect its sensitive contents, and he couldn't give out the passcode.

The border agent wouldn't relent. He needed to access the device, he said, and had the authority to do so. […].

Bikkannavar didn't feel like he had a choice. 'I'd read the headlines of people being stranded in airports and having problems entering the country, so I was still in the mode of being as cooperative and polite and courteous as possible,' he said to me."

Kaveh Waddell, "A NASA Engineer Was Required to Unlock His Phone at the Border," The Atlantic, February 13, 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/02/a-nasa-engineer-is-required-to-unlock-his-phone-at-the-border/516489/

16 CBP Directive No. 3340-049A Section 5.1.2 (pg.4)

17 Ibid.

18 U.S. Congress, Senate, To Place Restrictions On Search and Seizures of Electronic Devices at the Border, S 2462, 115th Cong., introduced in Senate February 27, 2018.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 CBP Directive No. 3340-049A Section 1 (pg.1)

22 United States v. Cotterman, 709 F.3d 952, 966 (9th Cir. 2013)(acknowledging child pornography is a legitimate concern and holding reasonable suspicion is a "modest, workable standard");

United States v. Kolsuz, No. 16-4687, 2018 WL 2122085 (4th Cir. May 9, 2018). (holding warrantless border searches of digital devices should, at minimum, adhere to a reasonable suspicion standard);

United States v. Touset, No. 17-11561, 2018 WL 2325350 (11th Cir. May 23, 2018). (deferring to legislature to set the standard of suspicion and admitting evidence obtained through forensic search based on reasonable suspicion).

23 Ibid.

24 Department of Homeland Security Small Unmanned Aircraft System (sUAS) Solicitation Number: HSHQDC-16-R-00114, last updated April 6, 2017. https://www.fbo.gov/index?s=opportunity&mode=form&id=5bb697a0dd83dccb4e…

25 "Harrison Rudolph, Laura M. Moy, Alvaro M. Bedoya, "Not Ready for Takeoff: Face Scans at Airport Departure Gates," Georgetown Law Center on Privacy & Technology. December 21, 2017. (pg. 2). https://www.airportfacescans.com/sites/default/files/Biometrics_Report__Not_Ready_For_Takeoff.pdf

26 CBP Releases Updated Border Search of Electronic Device Directive and FY17 Statistics, published by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, January 5, 2018. https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/national-media-release/cbp-releases-updated-border-search-electronic-device-directive-and

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.