Chair Landwehr and members of the Committee, my name is Michael F. Cannon. I am the director of health policy studies at the Cato Institute in Washington, DC.

The Cato Institute is a 501(c)(3) non-partisan, non-profit, tax-exempt educational foundation. Cato educates the public and policymakers about the principles of individual liberty, limited government, free markets, and peace. Cato scholars conduct independent research on a wide range of policy issues. To maintain its independence, the Cato Institute accepts no government funding. Cato receives approximately 80 percent of its funding from individuals. The remainder comes from foundations, corporations, and the sale of books and other publications. The Cato Institute takes no positions on legislation. No Cato donors have had any input into my testimony.

Thank you for the opportunity to comment on HB 2556, the “Cutting Healthcare Costs for All Kansans Act,”1 which would expand Kansas’ Medicaid program to cover able-bodied adults up to 138 percent of the federal poverty threshold.

In my 20 years as director of health policy studies at Cato, I have had the honor to visit the Kansas legislature on numerous occasions. In 2013, I testified against Kansas expanding Medicaid.2 The reasons I offered then remain true today:

- “Medicaid is rife with waste and fraud.”3

- “Medicaid increases the cost of private health care and insurance, crowds out private health insurance and long-term care insurance, and discourages enrollees from climbing the economic ladder.”4

- “There is scant reliable evidence that Medicaid improves health outcomes at all, and absolutely no evidence that it is a cost-effective way of doing so.”5

- “Historical experience with government health programs shows that enrollment and spending often dramatically exceed projections.”6

In 2019, I participated in a two-day, bicameral roundtable that focused broadly on expanding access to care for low-income Kansans.7 On both occasions, I warned that expanding Medicaid would be costly and counterproductive.

Also on both occasions, I offered reforms that would make health care better, more affordable, and more secure—particularly for the most vulnerable Kansans—without imposing any costs on Kansas taxpayers. Those reforms include:

- Recognize clinician licenses from other states, freeing competent clinicians to treat Kansas patients via telehealth or in person.

- Apply for a federal waiver to allow Kansas to conduct randomized, controlled trials that quantify the benefits enrollees and taxpayers receive from the Medicaid program.

- Let doctors and patients enact their own cost-saving and quality-improving medical malpractice liability reforms.

Kansas has wisely avoided expanding Medicaid and should continue to do so. But if Kansas lawmakers want to make health care more universal, they must adopt these and other reforms I detail below.

Not a Free Lunch

Experience shows that expanding Medicaid would impose larger burdens on Kansas taxpayers than current projections suggest. The Kansas Health Institute (KHI) projects that expanding Medicaid would increase combined federal and state government spending by $14 billion over 10 years. KHI further estimates that as a result of federal incentives and clever gaming of the Medicaid program, the state of Kansas—which is to say, Kansas taxpayers—would bear just 1 percent of that cost, on average $17 million per year.8

The burden on Kansas taxpayers would actually be much larger, for several reasons.

- First, in states that have expanded Medicaid, actual expenditures have exceeded pre-enactment projections by more than 32 percent.9 A conservative estimate would therefore be that total government spending and taxes would rise by $18 billion, and the average annual burden on Kansas taxpayers would be $22 million per year, over the first 10 years.

- Second, Kansas’ share would jump to 5 percent when federal incentives disappear after the second year, reaching $116 million per year by 2034.

- Third, Kansas’ share would inevitably rise even further. Congress cannot continue funding Medicaid at current levels. Federal budget officials project that by 2025, the U.S. debt will exceed 100 percent of U.S. GDP.10 Stein’s Law reminds us, “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.”11 When Congress finally faces a budget constraint, the change that both political parties in Washington, DC, have already proposed—shifting more of the cost of the Medicaid expansion to states12—will become inevitable.

Perhaps Not Even a “Lunch” at All

What would Kansas taxpayers be getting for all that additional cost? Research suggests the benefits to Kansas residents of expanding Medicaid are scant and uncertain. There remains little reliable evidence that expanding Medicaid has a net positive effect on health and absolutely no evidence that it is the best way to improve the health of targeted populations.

The most reliable evidence on the health impacts of the Medicaid expansion comes from Oregon. In 2008, the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment examined the effects of Medicaid by taking advantage of a policy that randomly assigned applicants to receive Medicaid or nothing, and then compared outcomes for the two groups. As it happens, the study examined able-bodied adults in the income range that would make them eligible for the Medicaid expansion. Even though researchers chose measures of physical health that were amenable to treatment over a two-year period, Medicaid enrollment “generated no [discernible] improvements in measured physical health outcomes in the first 2 years.”13 The lack of any improvement in physical health outcomes among Medicaid enrollees should throw a stop sign in front of the Medicaid expansion.

Similarly, there is no evidence that Medicaid expansion is cost-effective. The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment did find small improvements in self-reported mental health. But that study did not attempt to quantify whether state and federal governments could have purchased better health by spending those funds differently or enacting different reforms. Moreover, it found that “Medicaid’s value to recipients is lower than the government’s costs of the program,” with the “welfare benefit to recipients from Medicaid per dollar of government spending rang[ing] from about $0.2 to $0.4.”14

In the decade since I first alerted Kansas legislators to the lack of evidence of benefit of the Medicaid expansion, advocates could have adopted my recommendation to obtain a waiver that would have allowed the state to quantify those benefits. Had they done so, their argument for expanding Medicaid might be stronger than it is today.

Kansas lawmakers should not shoulder taxpayers with additional burdens when the value to enrollees is well below the cost to taxpayers, and when lawmakers can’t even identify what taxpayers are getting in return.

A Precarious Situation for Medicaid Enrollees

Even if all goes as supporters predict, expanding Medicaid would threaten access to care for current and new enrollees. The fact that the federal government would contribute a larger share of spending for the expansion population than for other Medicaid enrollees would make Kansas officials more likely both to increase spending on able-bodied adults and to cut spending on children, mothers, and the aged. One study found that expanding Medicaid “shift[ed] financial resources away from certain vulnerable enrollee populations, the most notable being from low-income children.”15 In addition, many potential Medicaid-expansion enrollees currently have health plans. Expanding Medicaid would cause them to lose those plans, thereby disrupting their access to care.

Moreover, all might not go as supporters predict. Expanding Medicaid would replace those plans with coverage that is much more likely to disappear. Kansas’ share of Medicaid-expansion spending would inevitably rise above both the 5 percent that KHI estimates and the 10 percent that federal law ostensibly requires.

As a result, expanding Medicaid would inevitably leave state officials with a choice between either imposing substantial tax increases or taking coverage away from substantial numbers of Kansans. Both options would harm low-income Kansans. Tax increases would eliminate economic opportunities that would otherwise help low-income Kansans become self-sufficient.

Withdrawing from the Medicaid expansion—which HB 2556’s sunset provision would make automatic if the official state share rose above 10 percent—would take coverage away from more Kansas residents than lost Medicaid coverage due to the covid “unwinding.” KHI projects 152,000 Kansans would gain coverage as a result of expanding Medicaid.16 If history is any guide, even more Kansans would lose coverage because actual enrollment would exceed those projections. Kansas officials estimate that as of the end of last year, 133,000 residents lost Medicaid coverage due to unwinding.17

Kansas Has Chosen the Responsible Course

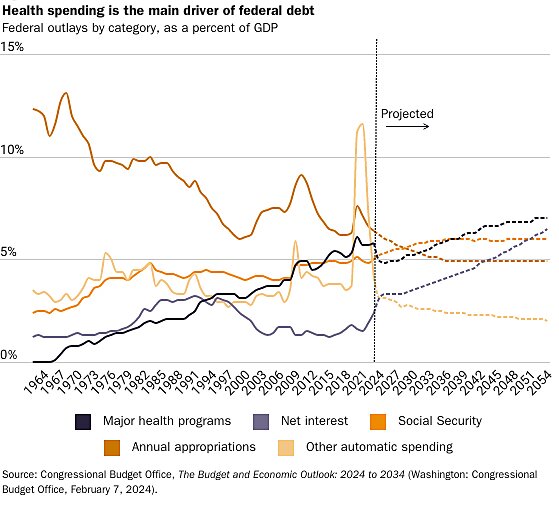

The federal debt is exploding primarily because states and the health care industry have gamed federal health programs, just as HB 2556 attempts to game the Medicaid expansion. The nearby figure illustrates that federal health spending is the primary driver of growth in the federal debt. So far, Kansas has chosen the responsible course by not making the problem of federal deficits and debt worse.

Contrary to what some Medicaid-expansion advocates claim, Kansas is not “leaving money on the table.” There are no pots of money that Congress has set aside to fund the Medicaid expansion in each state. To finance its share of a state’s Medicaid-expansion program, Congress issues additional debt. As a result, when a state implements the Medicaid expansion, state officials themselves trigger additional federal borrowing and debt. As I told this legislature in 2019, whether to implement the Medicaid expansion “is the biggest decision Kansas will make that will affect the federal deficit.”18

Kansas has so far done the right thing. A back-of-the envelope calculation suggests the state’s refusal to implement the Medicaid expansion prevented some $9 billion in additional federal debt from 2014 to 2024. If KHI projections and historical experience are any guide, Kansas lawmakers would increase the federal debt by $18 billion from 2025 through 2034 if they were to expand Medicaid now. Of course, that additional debt would hasten the collapse of the program.

Medicaid Is Not Economic Development

Nor would it benefit the state to use the Medicaid expansion to prop up failing hospitals. Research indicates that Medicaid is unlikely to save failing hospitals. One study comparing states that expanded Medicaid to those that did not reports that from 2013 to 2016, “while profit margins grew in non-expansion states, they plummeted by an average of 10 percent in expansion states over the same period.”19

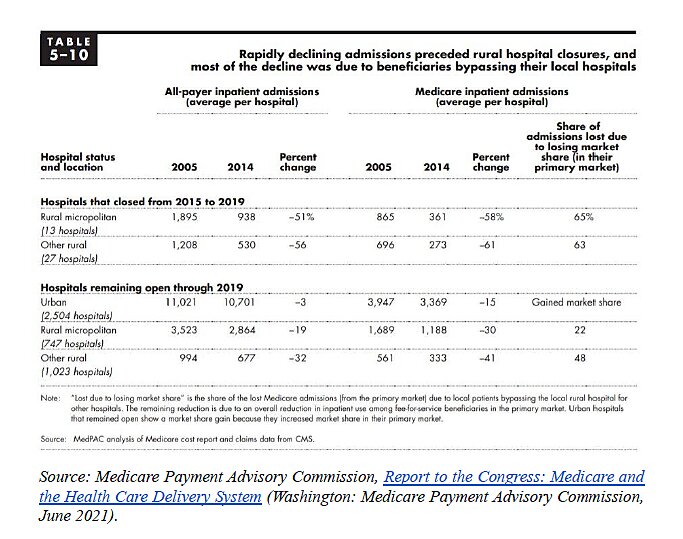

Even if expanding Medicaid did save failing hospitals, basic economics instructs that using Medicaid for this purpose would harm consumers. A federal study found that when rural hospitals closed, it was because on average they had lost more than 50 percent of their patients to competing hospitals.20

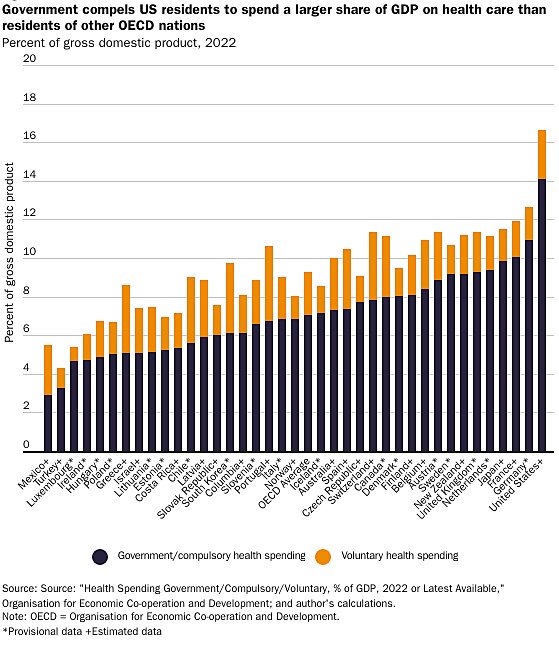

These hospitals are losing customers in a nation where compulsory health spending consumes a larger share of national income than in any other.

If a hospital cannot meet its customers’ needs even with the most lavish government subsidies in the world, the solution is not to provide more subsidies to those hospitals. It is to let those hospitals fail so others can use those resources to meet consumers’ needs.

As I told the legislature in 2019, “Medicaid is a health care program. The moment we start thinking about it as an economic development program, we should probably shut it down.”21

Positive Reforms to Make Health Care More Universal

Rather than expand Medicaid, there are many reforms Kansas lawmakers can enact that would bring health care within reach of low-income residents.

A partial list includes:22

- Recognize licenses from other states and third-party credentialing organizations.

- Eliminate Kansas’ statutory caps on damages in medical malpractice cases.

- Direct courts to enforce private contracts in which patients and providers agree on alternative medical malpractice liability rules.

- Recognize insurance licenses from other states and U.S. territories.

- Remove all restrictions on short-term, limited-duration health insurance.

- Allow non-Farm Bureau members to enroll in Farm Bureau plans.

- Remove barriers to assistant physicians providing primary care.23

- Allow psychologists with special training to prescribe psychotropic medications.24

I am eager to discuss these options with the committee.

I again thank the Chair and the committee for this opportunity.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.