Key Points

-

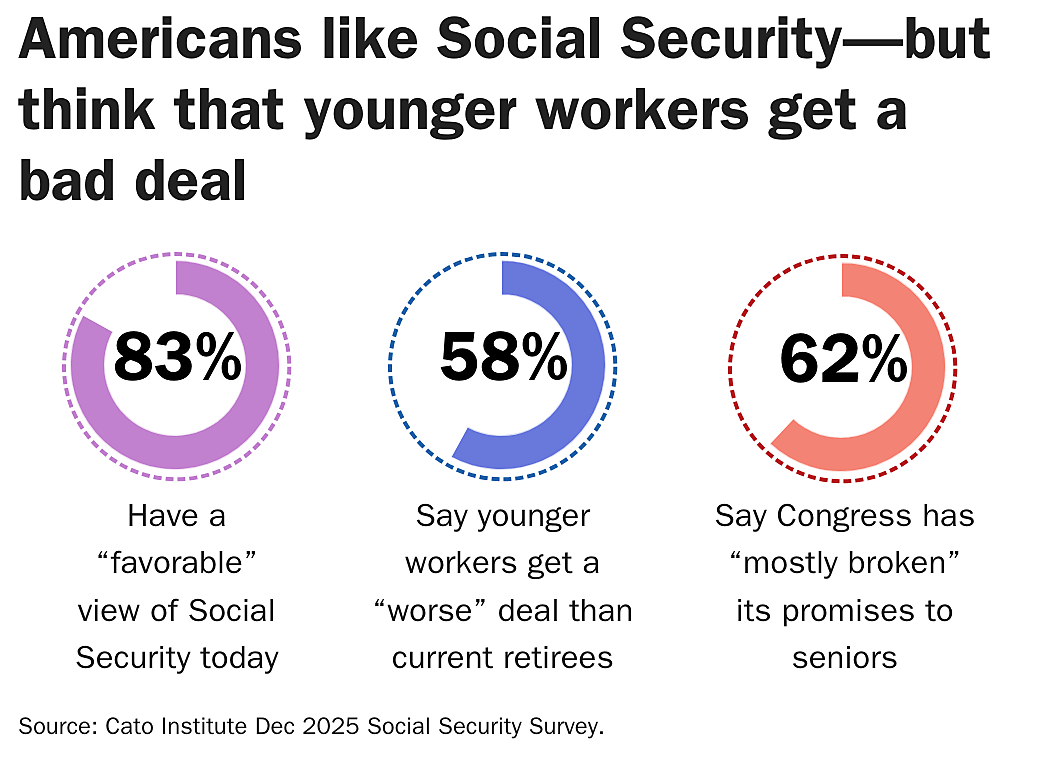

83% have a favorable view of Social Security.

-

30% believe Social Security will not exist when they retire.

-

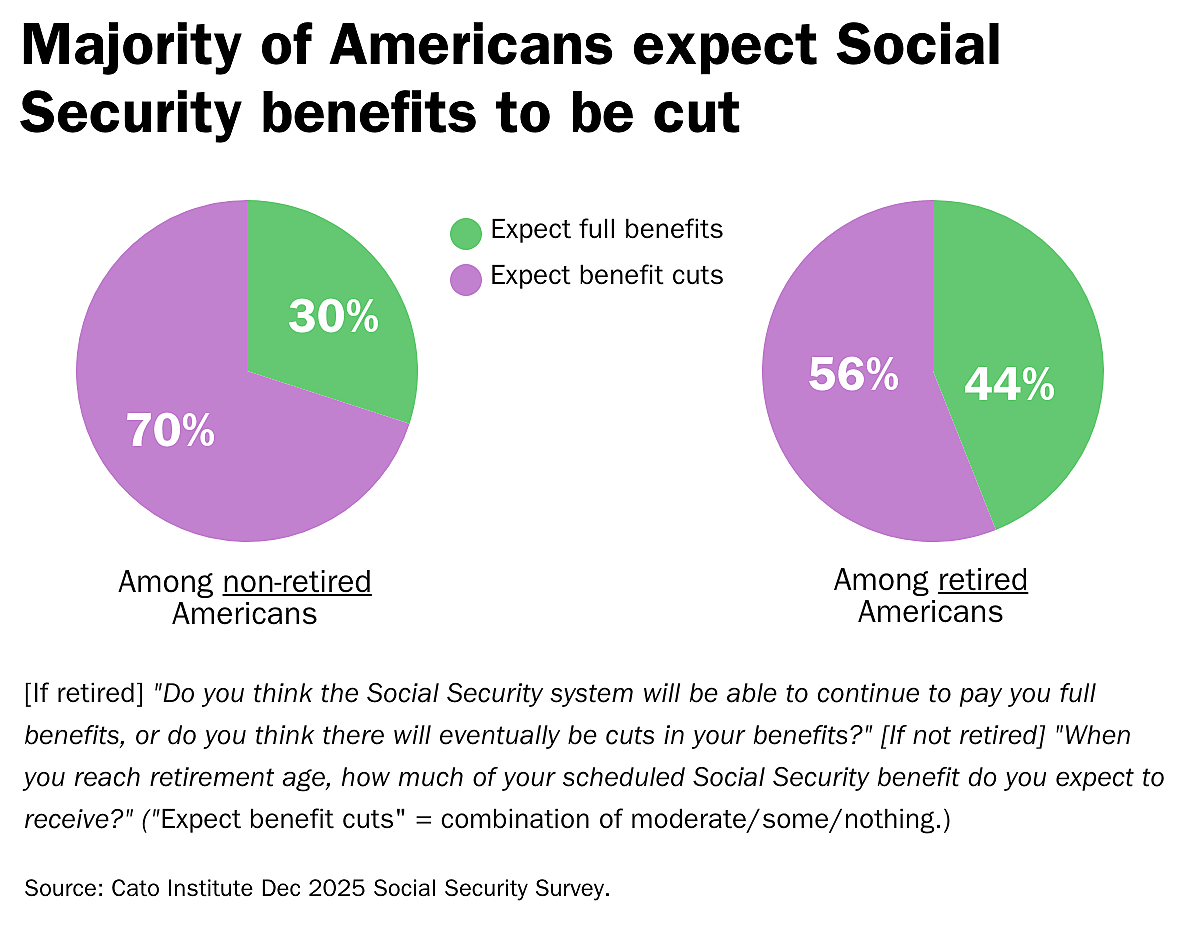

70% expect Social Security benefits to be cut in the future.

-

58% say younger workers are getting a worse deal than today’s retirees receive.

-

62% say Congress has “mostly broken its promises” in managing Social Security.

-

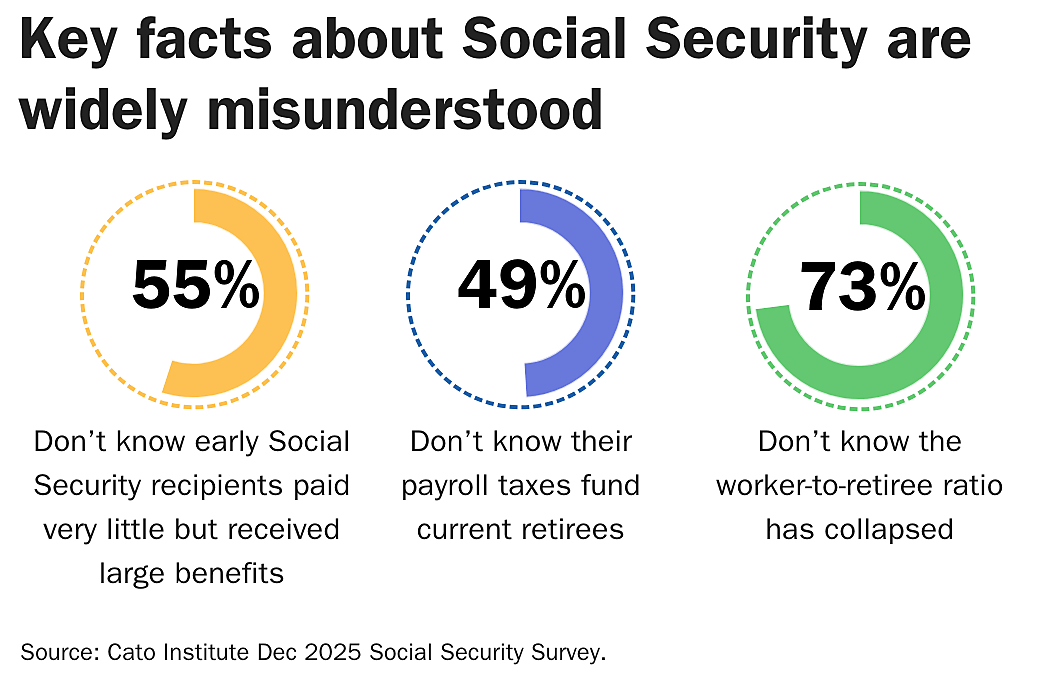

49% don’t know their payroll taxes fund current retirees’ benefits.

-

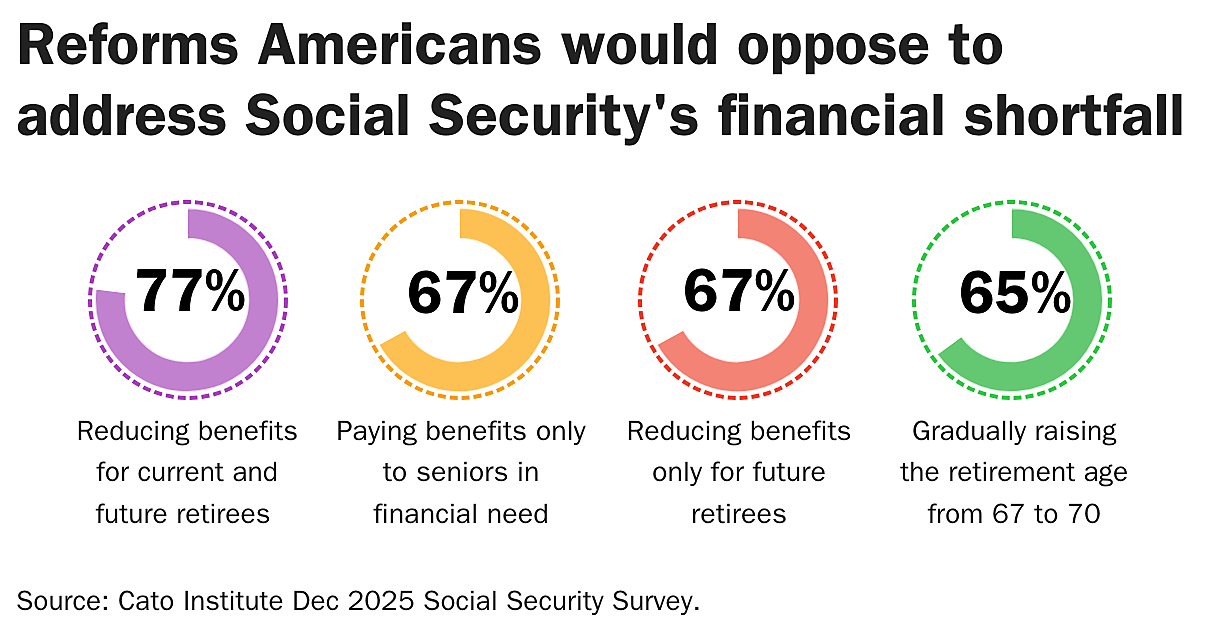

77% oppose cutting benefits for current and future retirees.

-

77% oppose raising their own payroll taxes by $1,300 per year.

-

71% support creating a nonpartisan commission to fix Social Security.

-

51% say they aren’t currently saving for retirement.

A new survey of 2,000 Americans from the Cato Institute in collaboration with YouGov finds that 83% of Americans have a favorable view of Social Security. This support spans party lines: 90% of Democrats, 82% of Republicans, and 81% of independents hold positive views. Most workers (82%) also expect Social Security to fund at least part of their income during retirement.

Resources

Yet, Americans express deep concerns about the program’s future. Seven in 10 Americans expect Social Security benefit cuts, and nearly a third (30%) believe the program will not exist when they retire (and 36% are unsure). A majority (58%) say Social Security offers younger workers a “worse deal” than current retirees receive, and nearly two-thirds (62%) believe Congress has broken its promises in managing the program. Notably, Democrats (60%) and Republicans (55%) agree that younger workers are getting a worse deal, and 58% of both groups believe Congress has broken its promises.

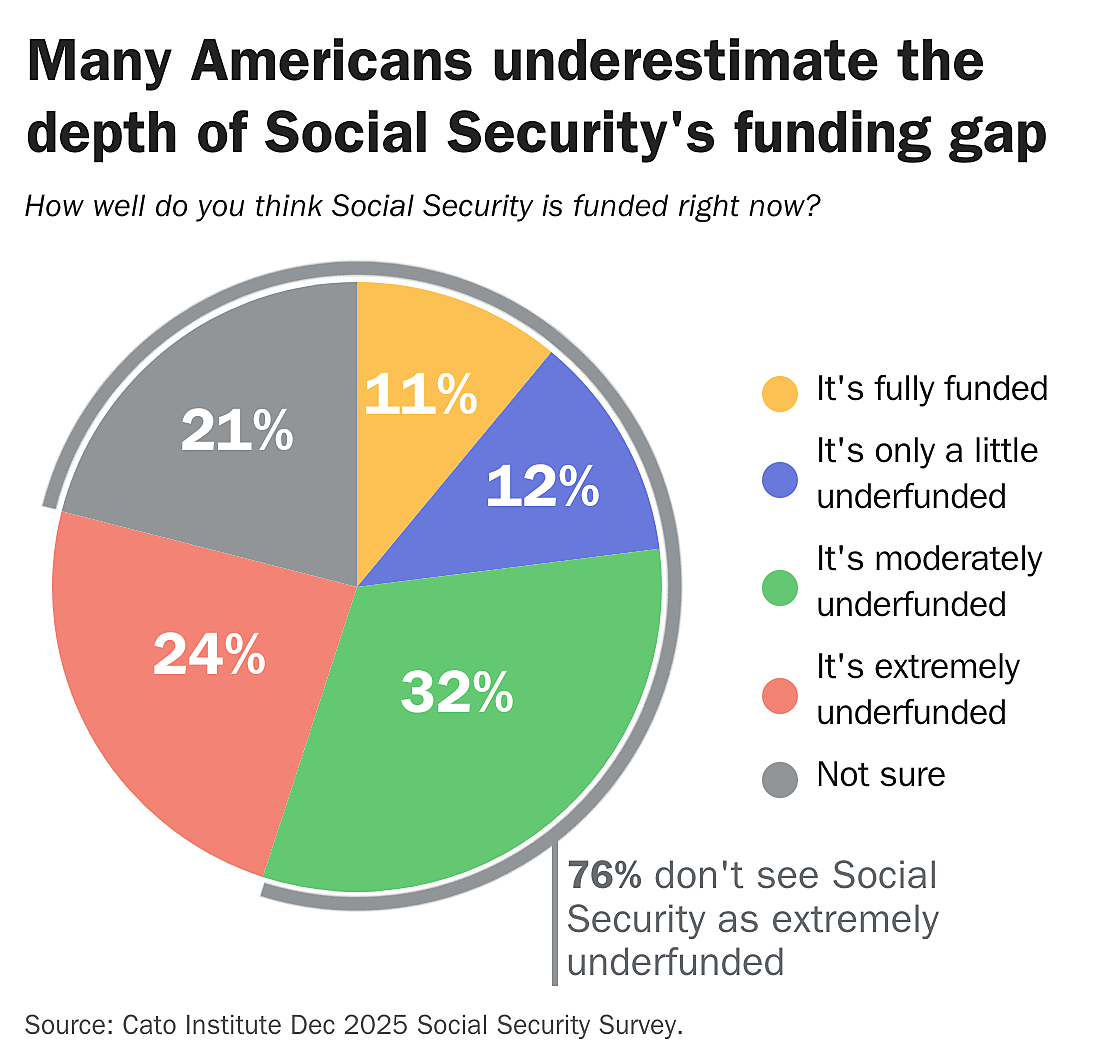

Americans underestimate the severity of Social Security’s financial problems, with 76% unaware that the program is extremely underfunded. When informed that benefits could be cut by nearly a quarter starting in 2033, almost half (44%) say the problem was more serious than they realized. This broad lack of public understanding poses a major obstacle to reform.

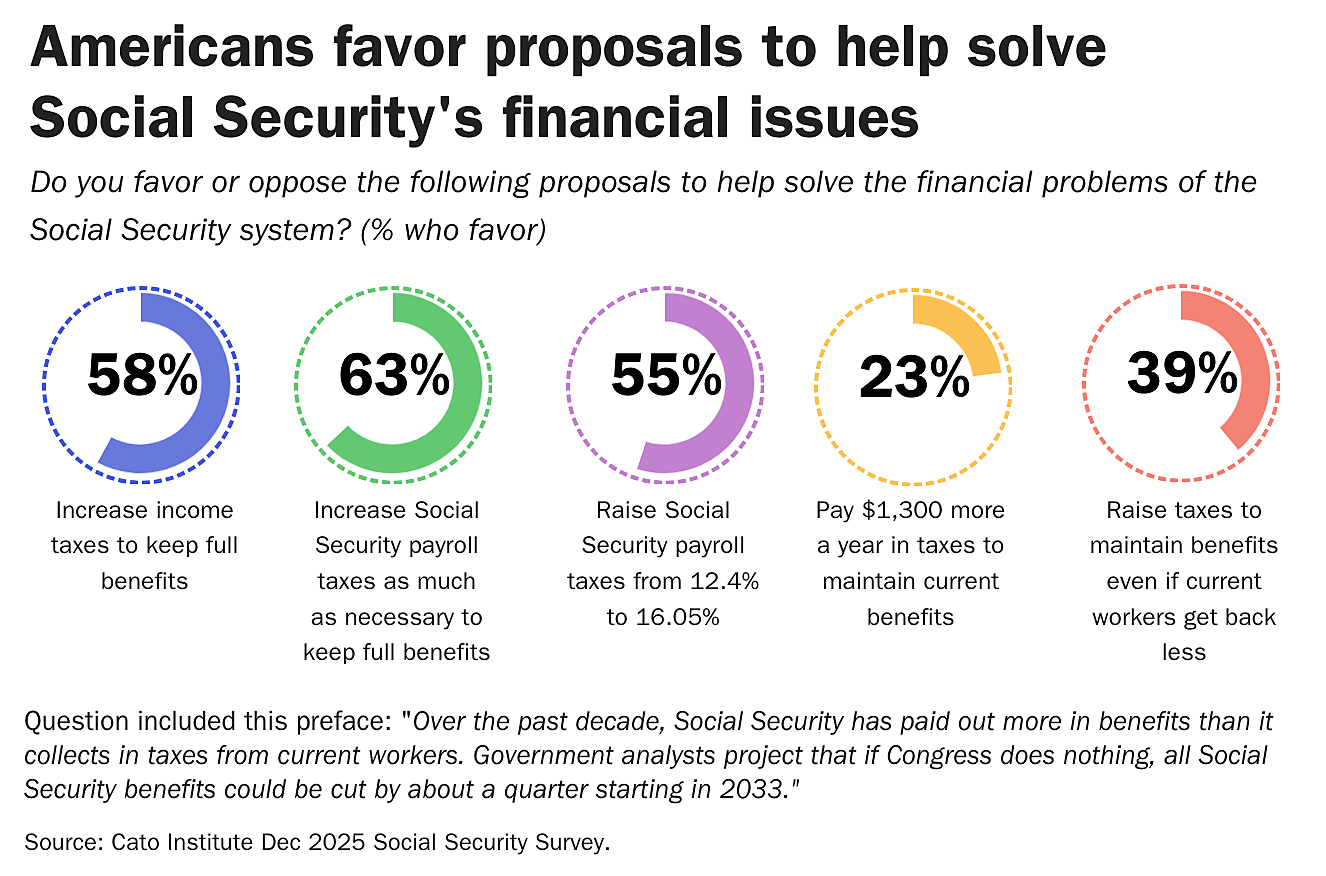

Americans favor small, targeted reforms, such as freezing benefits for one year (57%) or slowing cost-of-living adjustments (58%), that fit with their belief that Social Security is essentially a retirement savings plan they paid for (60%) rather than a welfare program (24%). But the public solidly opposes most major structural reforms required to address the long-term financing shortfall, including cutting benefits for current and future retirees (77%), cutting benefits just for future retirees (67%), paying benefits only to seniors in financial need (67%), or raising the retirement age to 70 (65%). Americans initially appear open to tax increases—for instance, 55% would support raising the payroll tax from 12.4% to 16.05%. But support collapses when framed in dollar terms: 77% oppose even a $1,300 annual tax increase—below what would be necessary to maintain current benefit levels. Moreover, 61% oppose tax hikes if current workers weren’t guaranteed to get back what they contributed.

One reform that Americans do support is delegating authority to an independent bipartisan national commission: 71% favor empowering such a commission to solve Social Security’s budget problems.

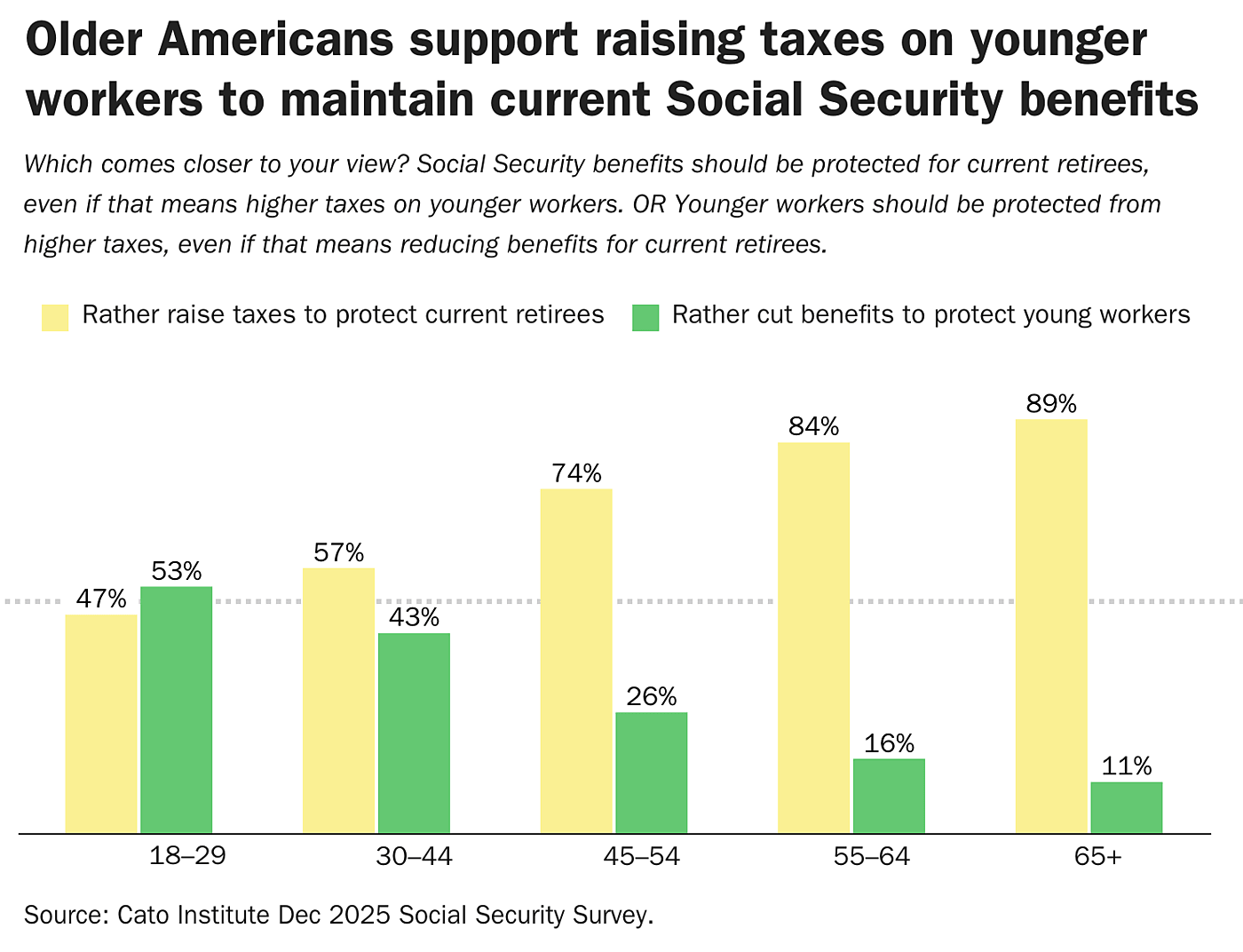

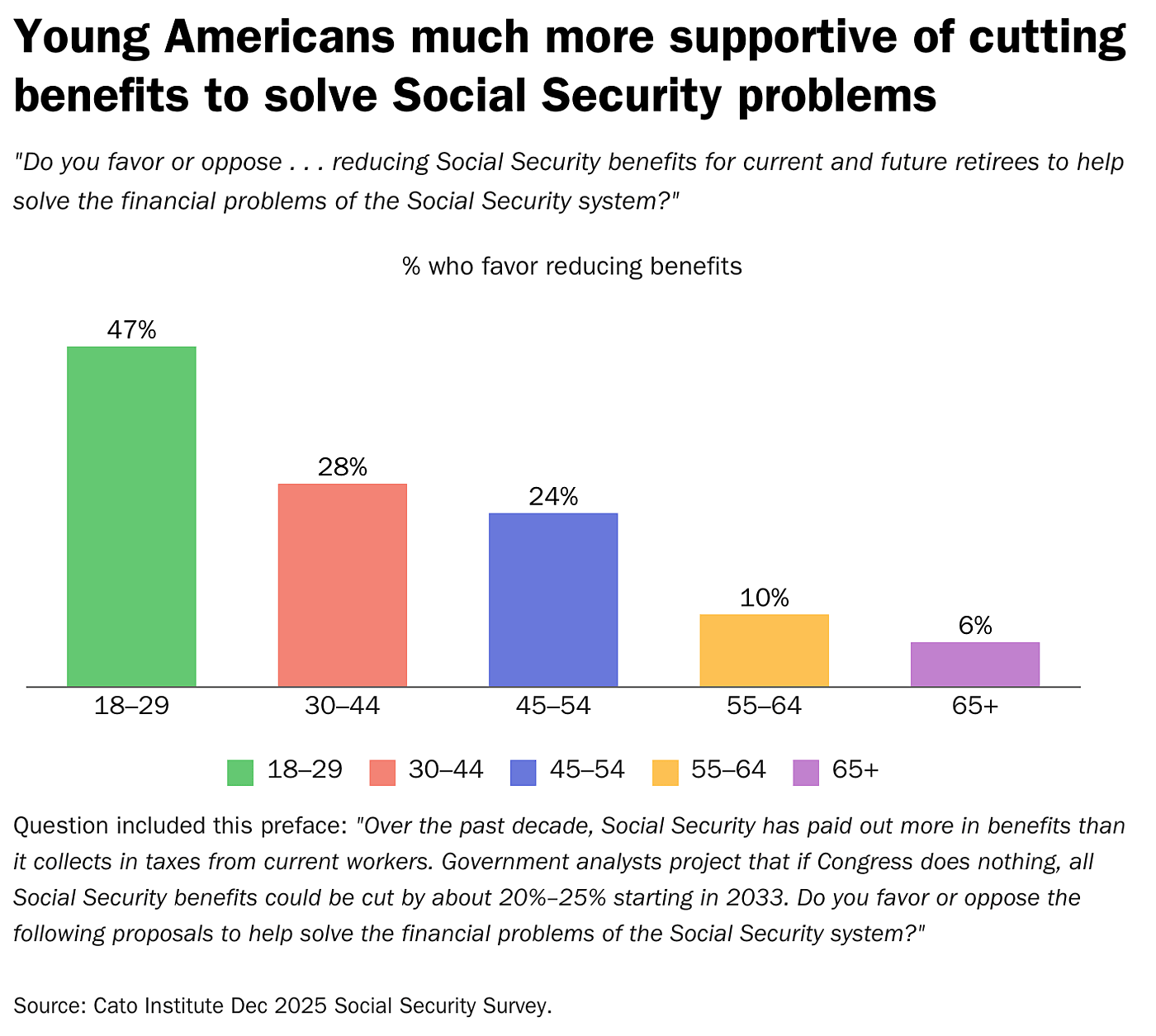

A striking generational divide emerges over Social Security reform. A majority (53%) of Americans under age 30 say younger workers should be protected from higher taxes even if doing so requires reducing benefits for current retirees. In sharp contrast, 89% of seniors age 65 and older believe current retirees’ benefits should be protected even if that means higher taxes on younger workers. Gen Z (defined here as Americans under 30) are eight times more likely than those 65 and older to support reducing benefits for current and future retirees to address Social Security’s financial problems (47% vs. 6%).

Americans Like Social Security, View It as a Retirement Savings Program

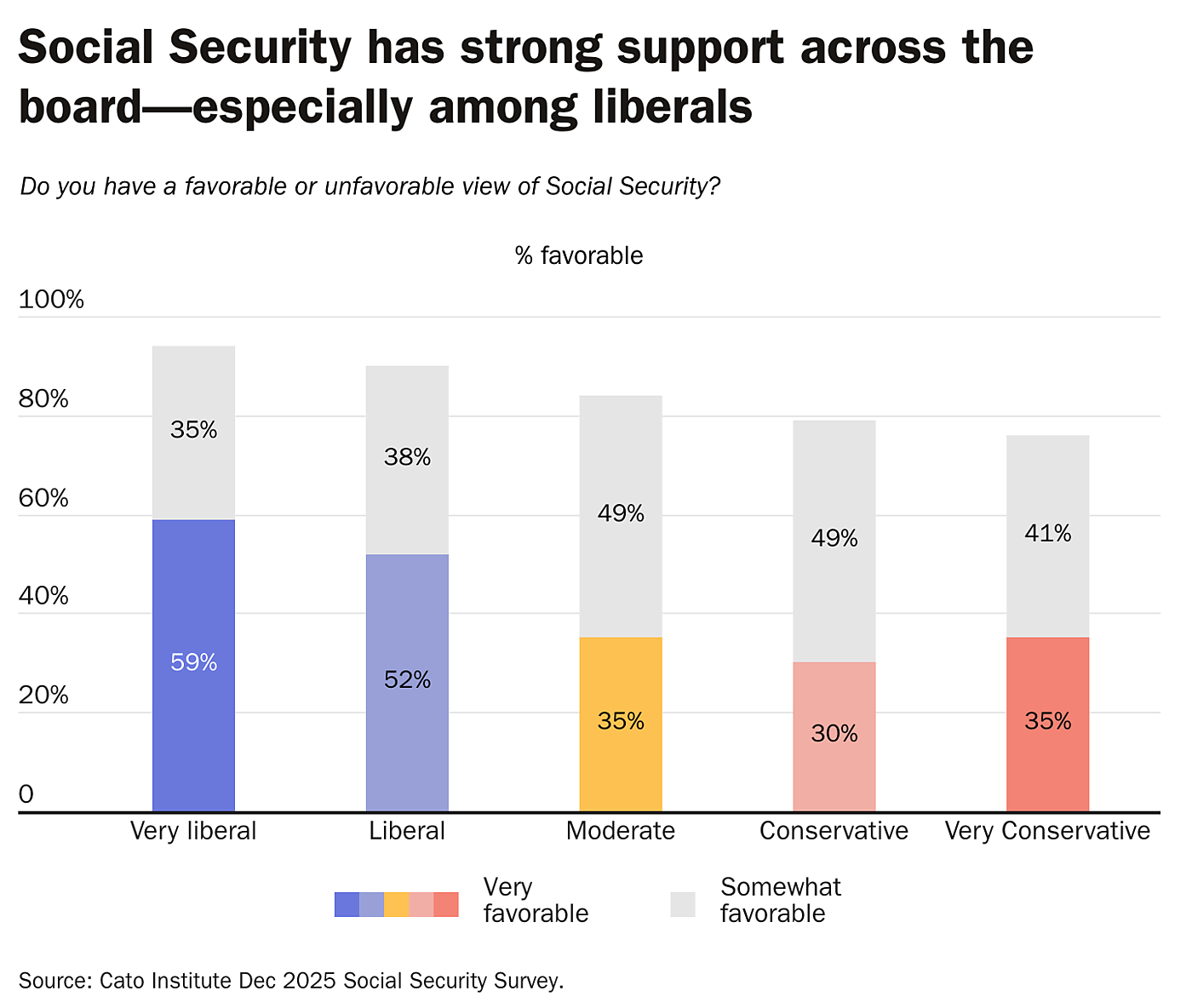

Americans overwhelmingly have positive views (83%) of Social Security, including 37% who have “very favorable” views. These views extend widely across party lines with 90% of Democrats, 82% of Republicans, and 81% of independents who agree. Most view it as a retirement savings program they paid for (60%) that later pays benefits in line with what each worker contributed (58%) rather than a welfare program (24%) or a program that redistributes to lower earners (23%). By extension, most workers (82%) today expect that Social Security will fund at least part of their income in retirement.

While Social Security is a universally popular program, Democrats feel more strongly about it, with 51% of Democrats compared to about a third of Republicans (31%) and independents (34%) who feel “very favorable” toward it. The more liberal a respondent the more strongly they feel, with 59% of strong liberals, 52% of liberals, 35% of moderates, 30% of conservatives, and 35% of strong conservatives feeling very favorable toward Social Security. This isn’t clearly a function of income: Americans earning less than $30,000 annually (34%) or earning between $30,000 and $60,000 annually (40%) were about as likely as those earning more than $150,000 annually (40%) to feel very positive about the program.

Half of Americans Aren’t Saving for Retirement; Most Expect Social Security to Partially Fund Their Retirement

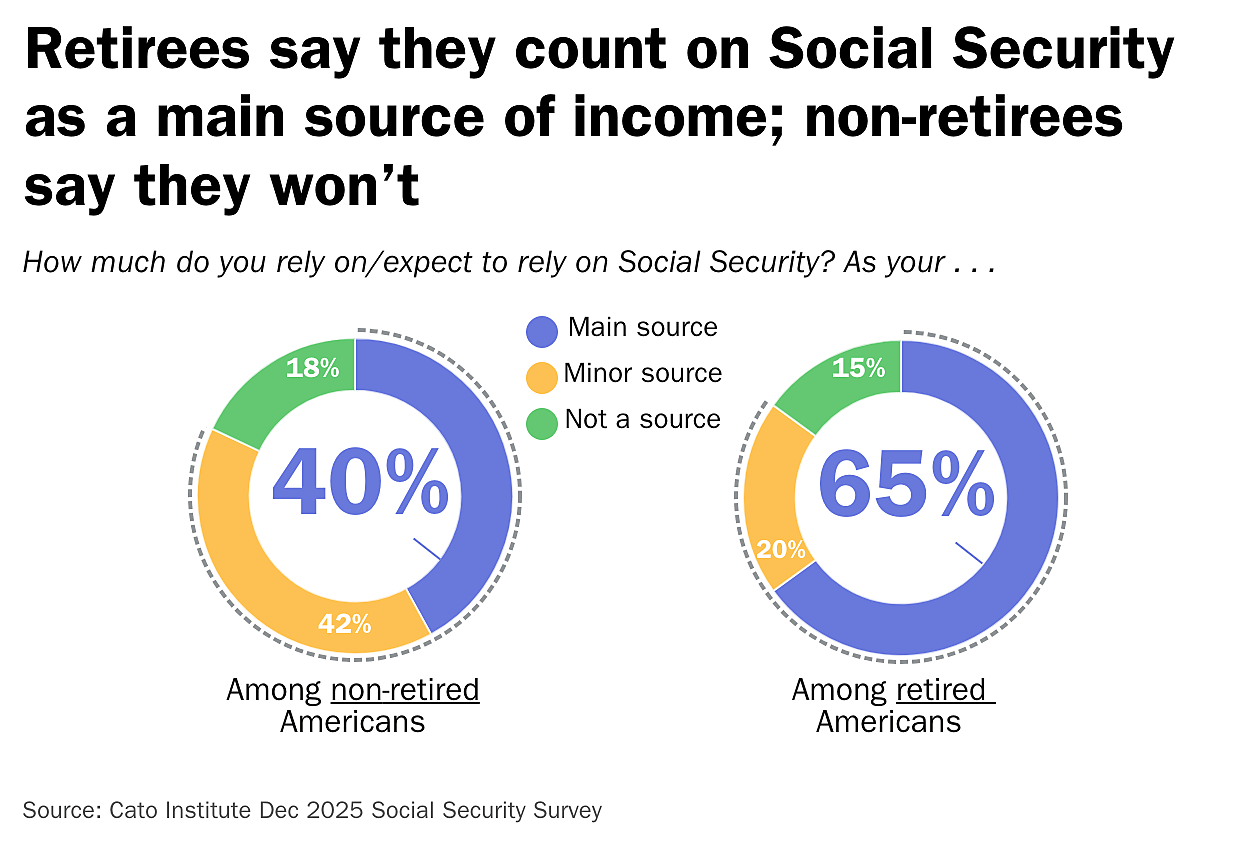

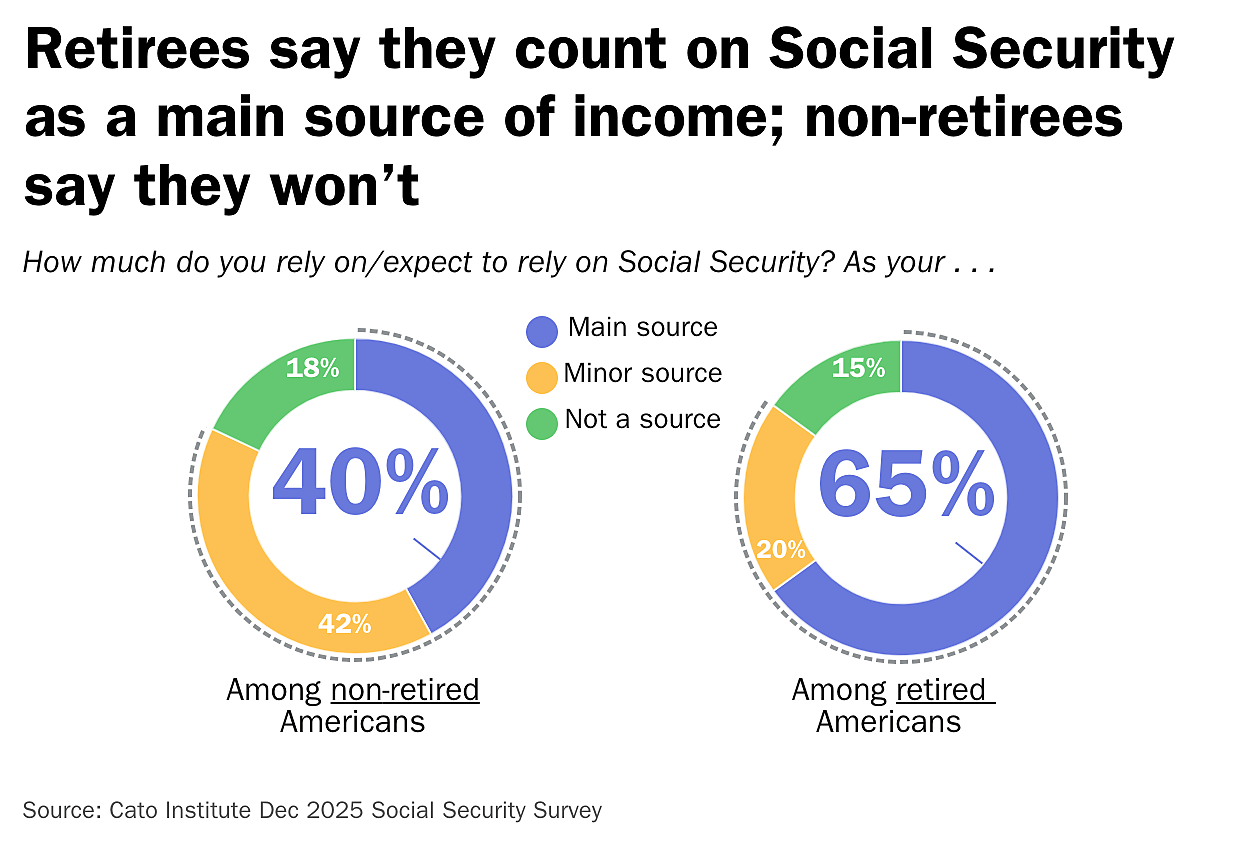

One reason people have such favorable views of Social Security may be that a little over half (51%) of working-age Americans say that they are not currently saving for retirement through a 401(k), IRA, or other means. Instead, an overwhelming majority (82%) of Americans say they anticipate benefits from Social Security will fund either a major (40%) or minor (42%) portion of their retirement income.

Americans Know Social Security Is in Financial Trouble but Underestimate Its Severity

Americans have serious concerns about the Social Security program’s longevity and benefit amounts. Most believe it’s unfair to younger workers. Most are aware that Social Security is underfunded, but most are unaware of its severity.

More than two-thirds (68%) of Americans are aware that Social Security is not fully funded, only 11% think it is, and 21% aren’t sure. Both retirees (56%) and current workers (70%) believe this to mean their benefits will be cut.

Some go even further—nearly a third (30%) think Social Security will not even exist when they retire—another 36% aren’t sure if it will.

Nearly two-thirds (62%) of Americans say that Congress’s management of the Social Security program has resulted in “mostly broken promises” to workers. Most believe benefit amounts are too low (54%), and even more (58%) believe Social Security offers a “worse deal” to younger workers compared to current retirees.

However, the public underestimates Social Security’s dire financial situation. When survey respondents were informed that benefits would need to be cut by about a quarter across the board if Congress does nothing starting in 2033, nearly half (44%) concede that the situation was “more serious” than they thought. Another 51% say it was about what they thought, and only 5% say this was less serious than they expected.

Few Understand the Structural Causes of Social Security’s Financial Problems

Few Americans understand the structural reasons behind Social Security’s severe financial problems. First, most are unaware that the earliest recipients contributed very little compared to what they received in benefits. In fact, a majority (55%) believe the first cohort either paid in more (18%) or about the same (37%) as they received. But this isn’t what happened.

Consider Ida May Fuller, one of the first recipients of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s new Social Security program. Adjusted for today’s dollars, she contributed only about $500 in Social Security taxes and then eventually collected about half a million dollars in benefits.

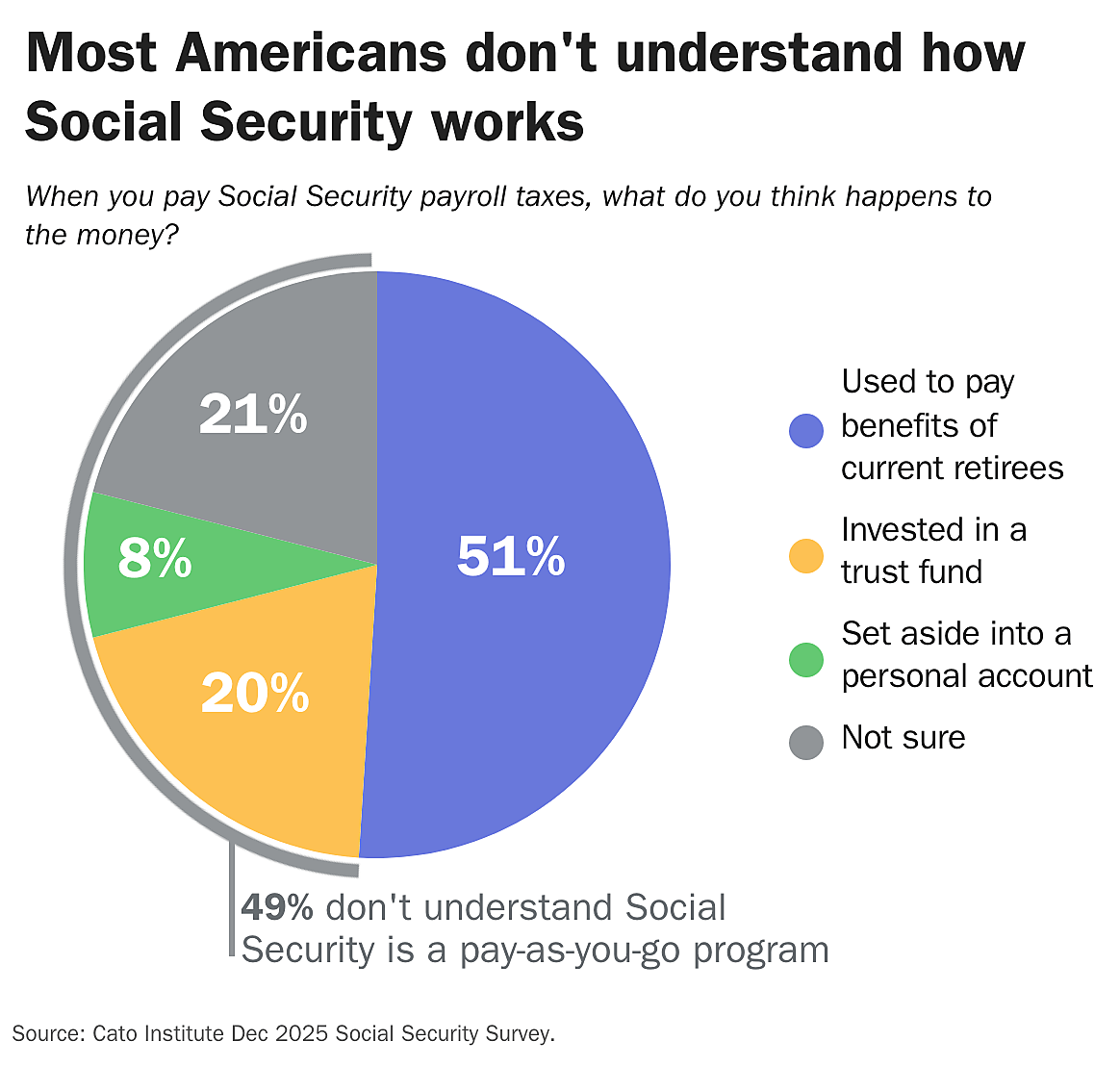

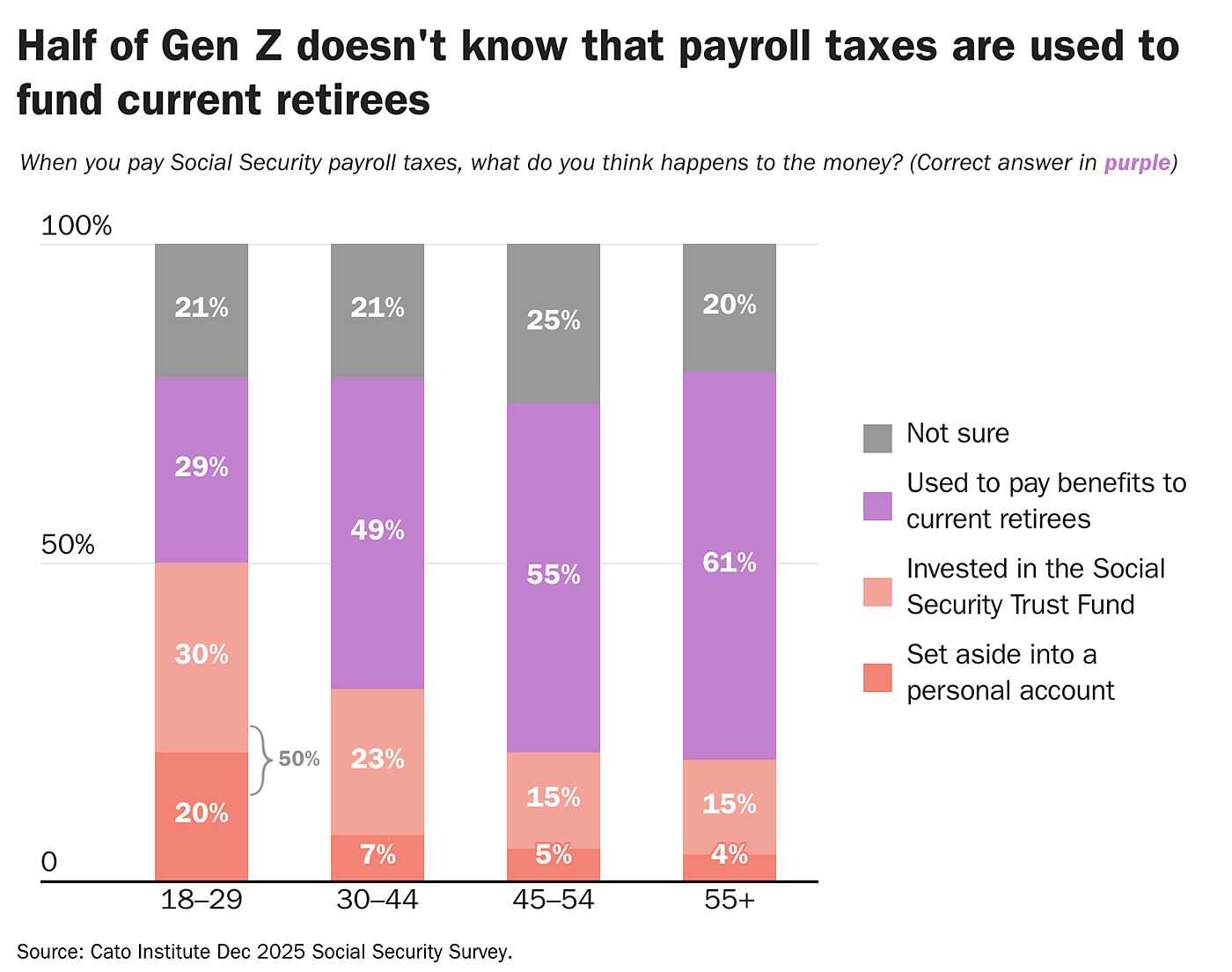

Second, about half (49%) of Americans do not realize that Social Security is a pay-as-you-go system in which current workers’ payroll taxes fund current retirees’ benefits—not the workers’ own future retirement. This misunderstanding reinforces the mistaken belief that Social Security functions similar to a personal retirement account.

Third, few understand how the program’s demographic foundations have shifted. In 1950, about 16 workers supported each retiree; today only 2.7 workers do. Yet, Americans are equally likely to say the number of workers per retiree has increased a lot (27%) as to say the number has decreased a lot (27%). In short, most do not know that the ratio of workers to

retirees has collapsed, sharply reducing the pool of contributors available to fund benefits.

Americans need a clearer understanding of these dynamics: the small contributions of early beneficiaries, the pay-as-you-go design, and the dramatic shrinking of the worker base. Without grasping these facts, the public cannot understand why Social Security is not a retirement savings program and why the system has such a significant shortfall. This lack of understanding makes it more difficult for policymakers and reformers to build public support for necessary changes.

The Public Doesn’t Understand How Social Security Works

➤ Half don’t understand Social Security’s pay-as-you-go structure

Nearly half (49%) of Americans don’t understand that Social Security is a pay-as-you-go program. Instead, 20% think that their Social Security payroll taxes are “invested” in the “Social Security Trust Fund” on their behalf until they retire, 8% think their taxes are saved in a personal account for them, and 21% concede they aren’t sure what happens to their payroll taxes. Just over half (51%) think payroll taxes are used to fund current retirees. Young Americans are far less likely to know this, only 29% of Americans under age 30 think their payroll taxes pay for current retirees compared to 61% of Americans over age 55.

➤ Only one in five Americans know how much they pay in payroll taxes

Most Americans don’t know the payroll tax rate they pay. Only 17% know that the combined payroll tax that employer and employee pay is about 12%. About a quarter (23%) think it is 6%, 10% think it is 3%, 7% think it is 16% or more. Nearly half (43%) concede they aren’t sure what the payroll tax rate is.

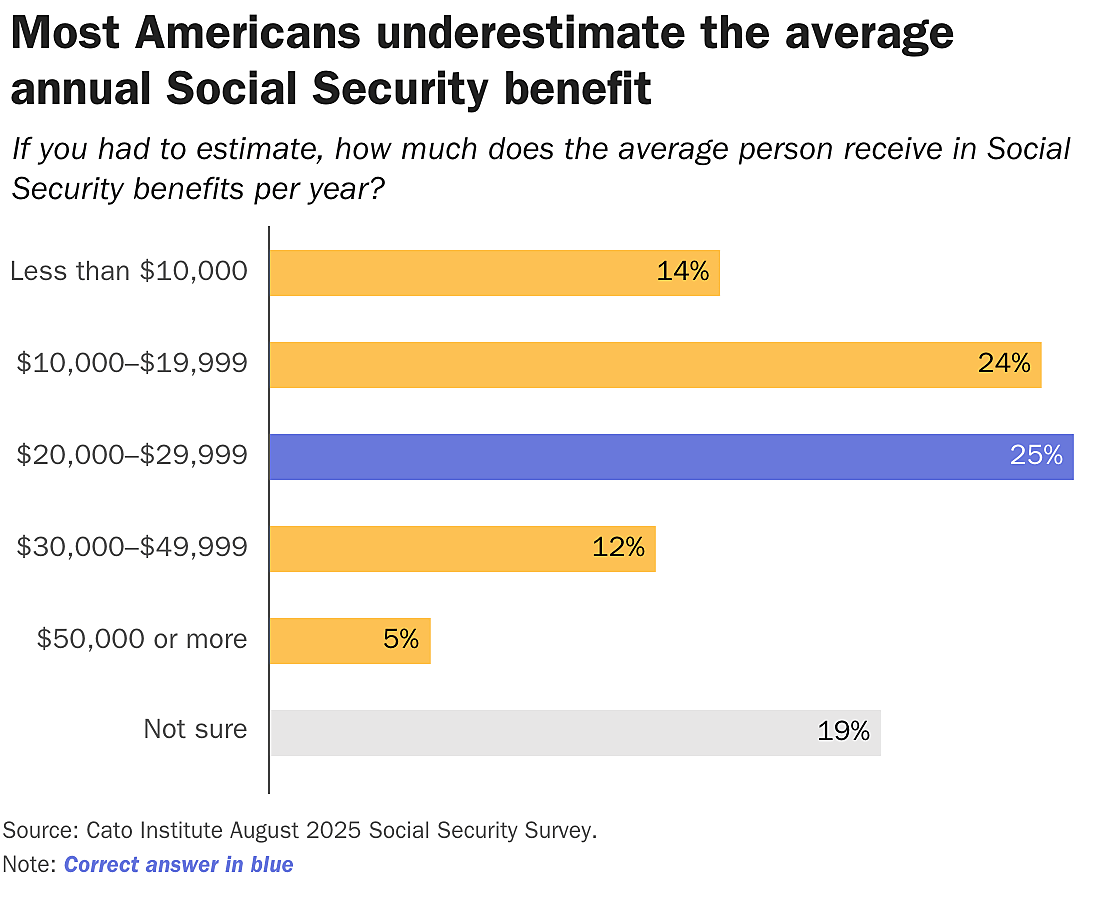

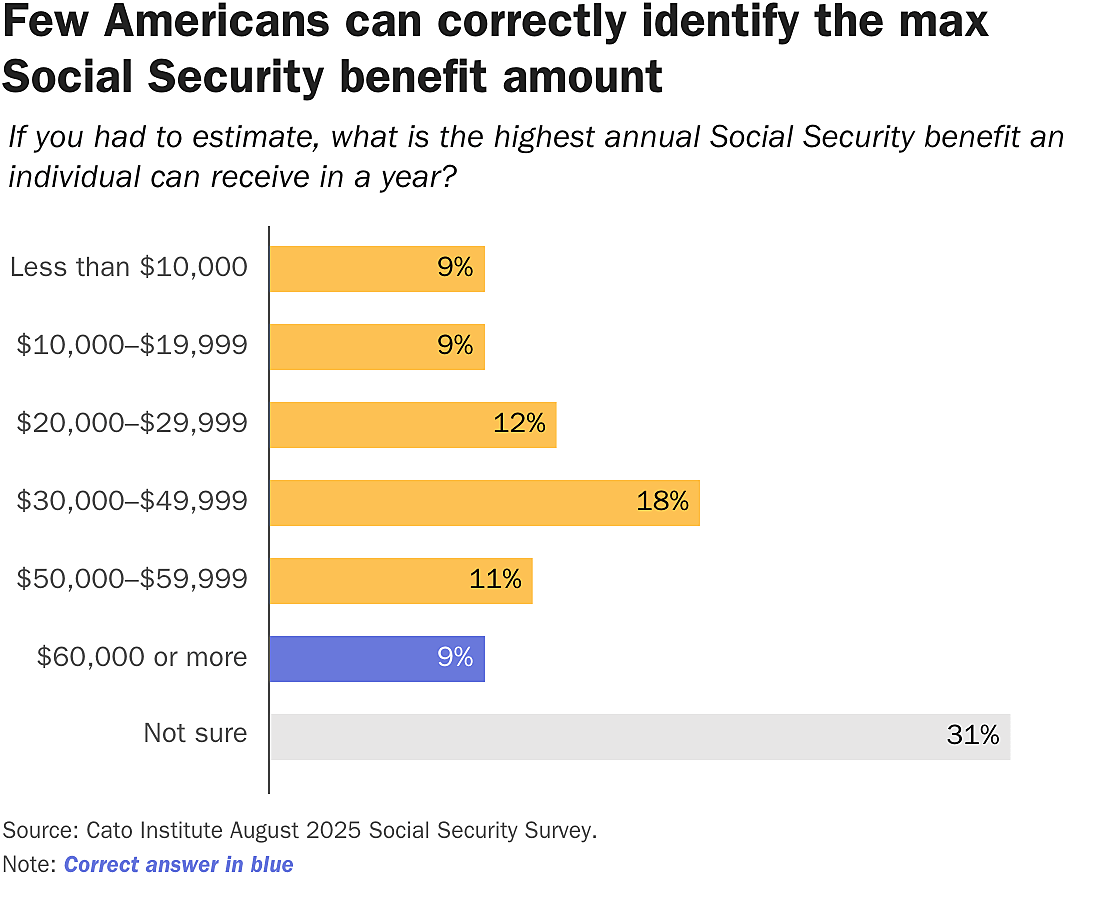

➤ Many underestimate how high Social Security benefits can be

When given a set of options, only a quarter (25%) correctly say that the average person receives between $20,000 and $30,000 in Social Security benefits a year. Thus, three-fourths (75%) of Americans do not know the average amount Social Security pays out in benefits: 38% underestimate the amount believing it’s something less than $20,000 a year, 17% overestimate the average amount, and 19% say they aren’t sure.[1]

Only 9% are aware that the highest annual Social Security benefit an individual can receive in a year is a little over $60,000 annually. Nearly two-thirds (60%) underestimate the highest benefit amount, and 31% report they don’t know.

➤ Most don’t know when people become eligible for Social Security

Most Americans don’t know when people become eligible for Social Security. Only 50% know that Americans could begin receiving some form of benefit at age 62, and only 39% know full benefits start at age 67.

➤ Most don’t know Social Security redistributes money

Few Americans realize that Social Security is redistributive—lower earners generally receive more than they paid in, while higher earners receive less. Only 28% correctly understand this. A third (33%) believe everyone gets back roughly what they contributed plus some interest, and a plurality (40%) say they’re not sure. Social Security was designed such that lower-income earners receive a higher replacement rate relative to what they paid in and higher income earners receive a lower replacement rate relative to their contributions.

Taken together, the public’s limited understanding of Social Security’s structural problems and basic mechanics—ranging from its pay-as-you-go financing to benefit levels, eligibility rules, and demographic pressures—creates major obstacles to building support for realistic solutions.

➤ Universal and contributive

Americans perceive Social Security to be a universal and contributive program, meaning that they do not believe it’s welfare but an enforced retirement savings plan. An overwhelming majority (86%) believe that “all who have paid into the system” should receive Social Security benefits, and only 14% think that benefits should be reserved for “those in financial need.” Seniors reach near universal consensus (97%) that benefits should be paid to all who contributed, which is 26 points higher than the share of Americans under age 30 (71%) who agree.

➤ Proportional

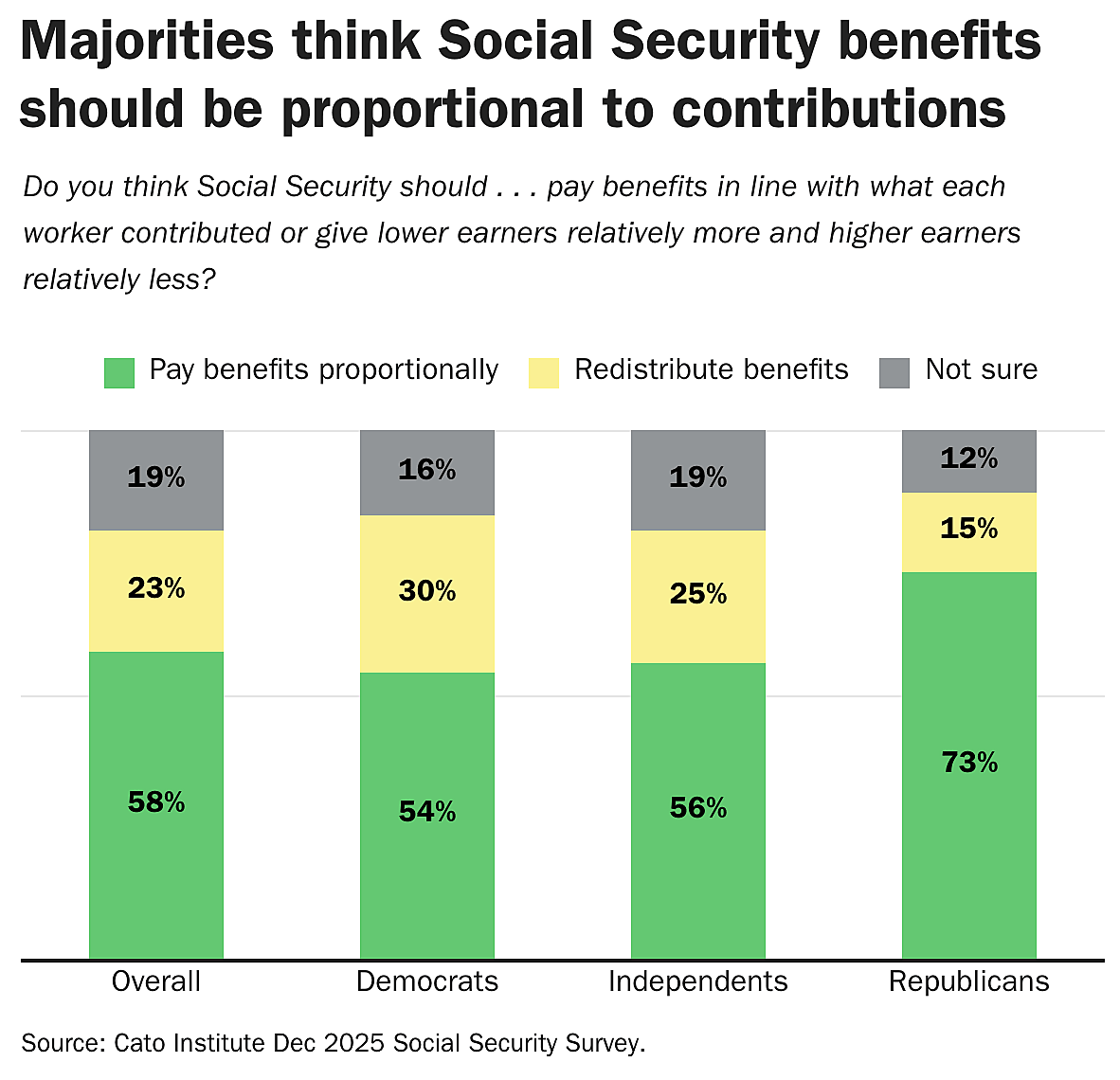

A solid majority (58%) think that Social Security benefits should be in line with or proportional to the amounts that workers contributed. Far fewer, about a quarter (23%), think that the program should redistribute such that lower earners get relatively more and higher earners get relatively less than they contributed; 19% aren’t sure either way. Notably, majorities of Democrats (54%) and Republicans (73%) believe in a proportional system, while Democrats (30%) are more comfortable with a redistributive structure than Republicans (15%) are. An overwhelming majority (70%) of seniors compared to less than half (47%) of those under age 30 think benefits should align with what each worker contributed.

➤ Replace incomes

Most do not think of Social Security as a social insurance program to protect seniors from poverty, as Franklin D. Roosevelt and New Deal planners imagined. Instead, 55% of Americans believe the “main purpose” of Social Security is to “largely replace seniors’ incomes after they retire.” Less than half (45%) view it as a program to ensure “no senior falls below the poverty line.” Democrats (52%), independents (54%), and Republicans (59%) view Social Security as an income replacement program, but Democrats are more supportive of the view that it’s an anti-poverty program.[2]

There is a significant generational divide, with a majority of Americans over age 65 who say it’s an income replacement program (60%), while a slim majority (52%) of Americans under age 30 say it’s an anti-poverty program.[3]

➤ Not welfare

Americans do not believe Social Security is a welfare program. When asked if they think of Social Security as more like a retirement savings program or a welfare program, nearly two-thirds (60%) say they think of it as a “retirement savings program [they] paid for.” About a quarter (24%) think of the program as a “welfare program that provides benefits.” Another 15% aren’t sure either way.

➤ Reward work

The survey also examined views of the earnings test, which reduces benefits for recipients who continue working (with those reductions later credited back). Nearly two-thirds (61%) of Americans say beneficiaries should be able to work and earn as much as they want without having their Social Security benefits reduced.

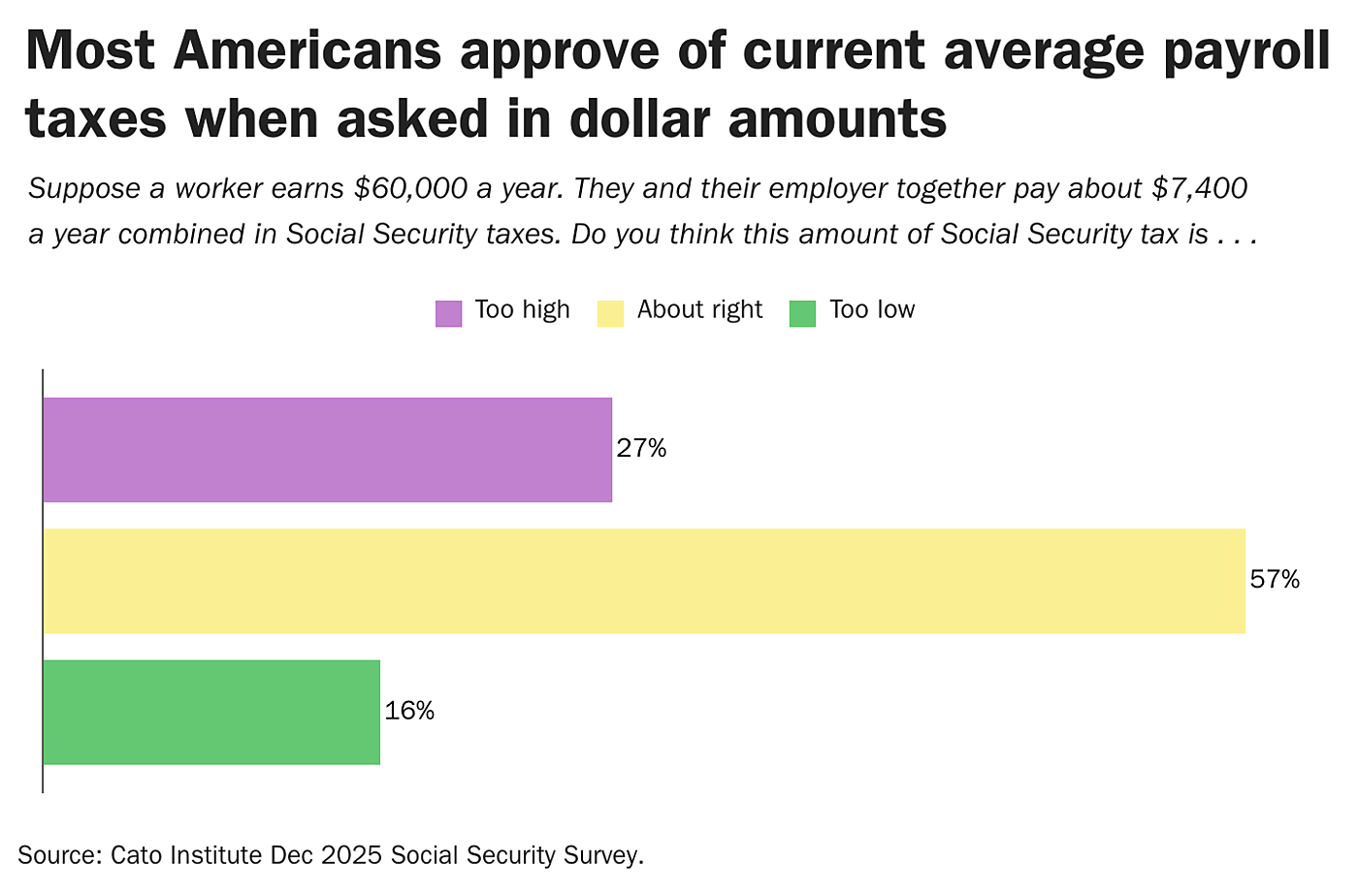

➤ Fair taxes

Most Americans think today’s Social Security payroll tax burden is reasonable. To assess perceptions of fairness, the survey presented respondents with a typical worker earning $60,000 a year who, together with their employer, pays about $7,400 in Social Security taxes. A majority (57%) say this amount is “about right,” while 27% think it is too high and 16% think it is too low.

Reforms Americans Support to Address Social Security’s Financial Problems

Reform will be necessary if Americans wish to avoid dramatic across-the-board Social Security benefit cuts or payroll tax increases. The survey explained to respondents, “Over the past decade, Social Security has paid out more in benefits than it collects in taxes from current workers. Government analysts project that if Congress does nothing, all Social Security benefits could be cut by about a quarter starting in 2033.” Respondents were then asked how they felt about a variety of potential reforms.

Tax reform: Americans oppose tax increases necessary to close budget shortfall

When confronted with a roughly 25% benefit cut starting in 2033, Americans initially say they would rather raise taxes (35%) than cut benefits (14%) or borrow money (17%). About a third (34%) are unsure. But further probing shows that Americans are not willing to raise taxes nearly enough to maintain current benefit levels.

When asked what types of tax increases Americans would support in general terms, solid majorities say they would favor raising “income taxes” (58%) or “payroll taxes as much as necessary” (63%) to keep benefits intact. More specifically, a majority (55%) say they support raising payroll taxes from 12.4% to 16.05%.

But framing tax increases in dollar amounts produces a very different response.

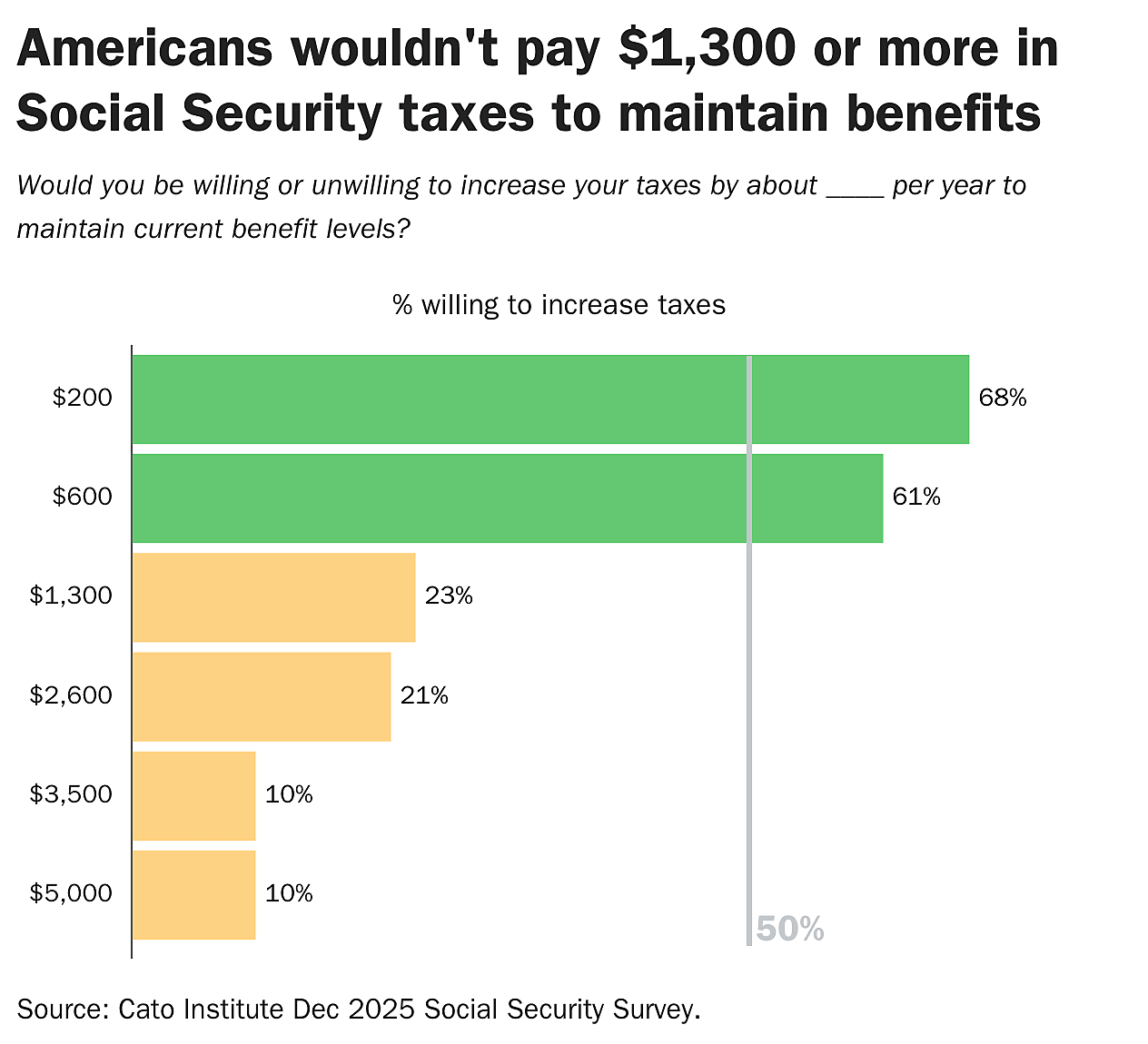

Most Americans don’t think in terms of percentages. When asked in concrete dollar amounts if they would be willing to raise their own taxes by $1,300 per year to maintain current benefits, an overwhelming majority (77%) say no. Yet, the realistic tax increase needed for the average worker is roughly $2,600 more per year, far above what the public is willing to pay.

When offered a range of annual tax increases to avoid benefit cuts, Americans support smaller increases: $200 more per year (68% support) and $600 more per year (61% support). However, majorities would oppose if taxes needed to be raised $1,300 per year (77% opposed) $2,600 per year (79% opposed) or higher. Nine in 10 reject increases of $3,500 or $5,000 per year. The survey did not test amounts between $600 and $1,300 so the exact inflection point remains unclear.

These patterns hold across income levels. For instance, Americans earning more than $150,000 per year are about as unwilling as a person earning less than $30,000 per year to pay an additional $2,600 per year in payroll taxes (75% and 78%, respectively). Strong majorities of both Democrats (73%) and Republicans (86%) also oppose tax increases at the projected $2,600 level needed to maintain benefits.

Tax reform: Americans want to personally benefit from a tax increase.

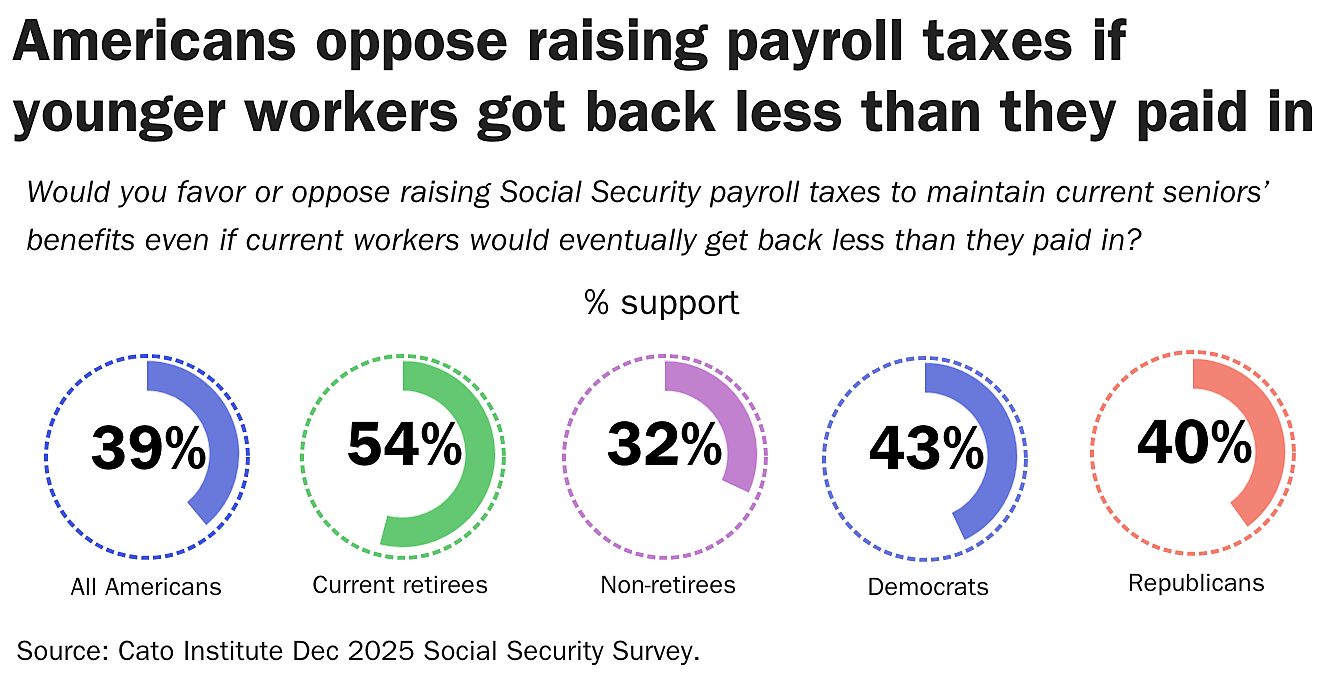

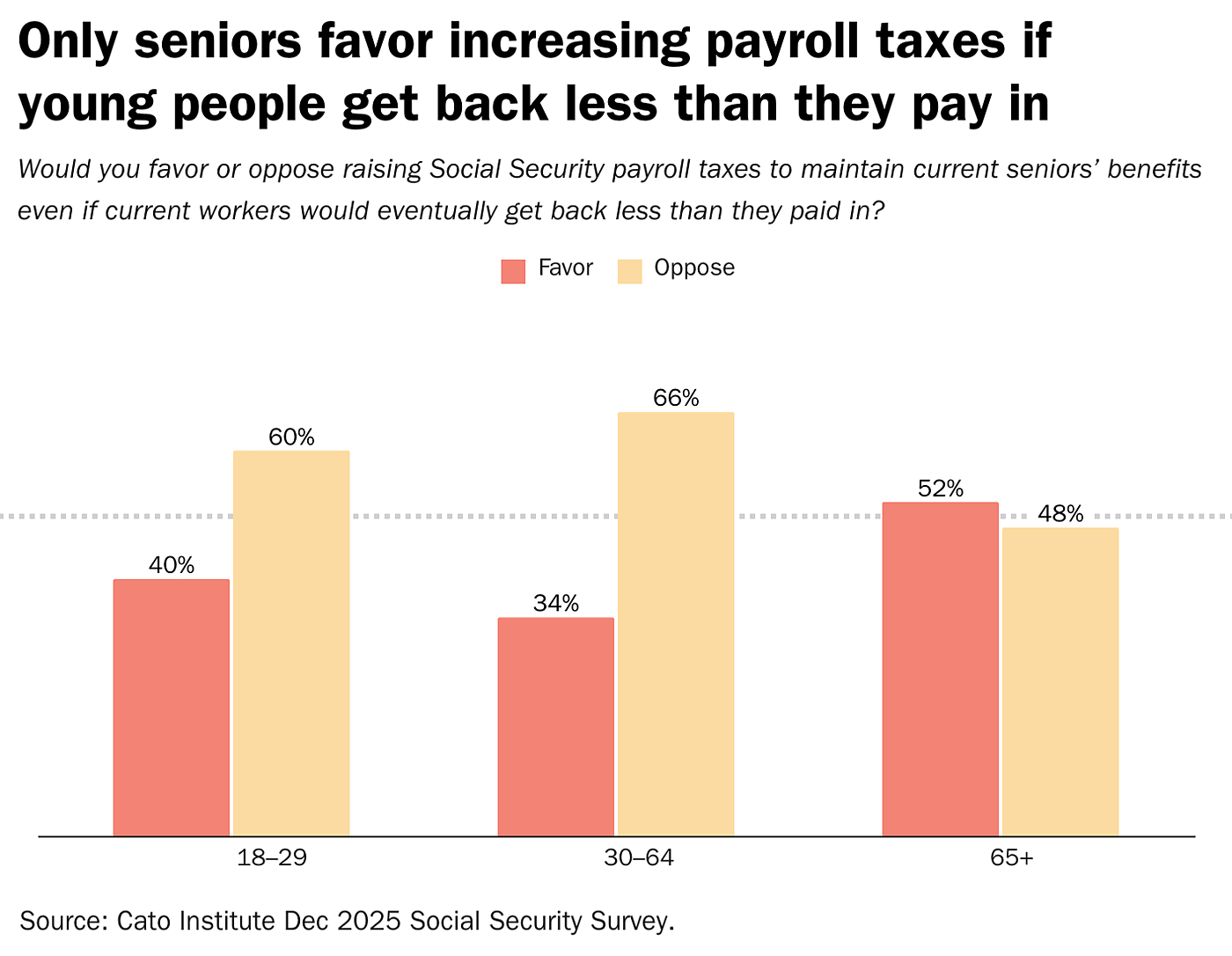

Taxpayers also don’t want to pay higher Social Security taxes if they would not personally benefit. For instance, nearly two-thirds (61%) oppose raising payroll taxes to maintain current seniors’ benefits if doing so meant today’s workers would ultimately receive less than they contributed. Majorities across parties—Democrats (57%), Republicans (60%), and independents (61%)—are also unwilling to pay higher taxes to preserve current benefit levels for seniors if they don’t get back what they contributed.

Current retirees, however, feel differently. A majority (54%) of Social Security recipients support raising payroll taxes to maintain their own benefits, even if younger workers would ultimately receive less. Among people who are not yet receiving Social Security, the opposite view prevails: 68% oppose raising their payroll taxes if doing so would not benefit them.

In sum, Americans are unwilling to raise taxes to the level required to close Social Security’s funding gap. They tolerate small increases but reject the much larger increases needed to sustain current benefits. These findings also suggest that the public evaluates taxes through a personal lens: Americans will support higher payroll taxes only if they believe those contributions secure their own future benefits. If higher taxes would primarily benefit someone else, as in a pay-as-you-go system, they oppose them. This reflects a widely held belief that Social Security functions similar to a mandatory personal retirement plan rather than a redistributive program. Policymakers attempting to preserve the status quo through tax increases may therefore encounter resistance if the public is convinced they will not receive proportional value for what they pay.

Reforms Americans say they would support

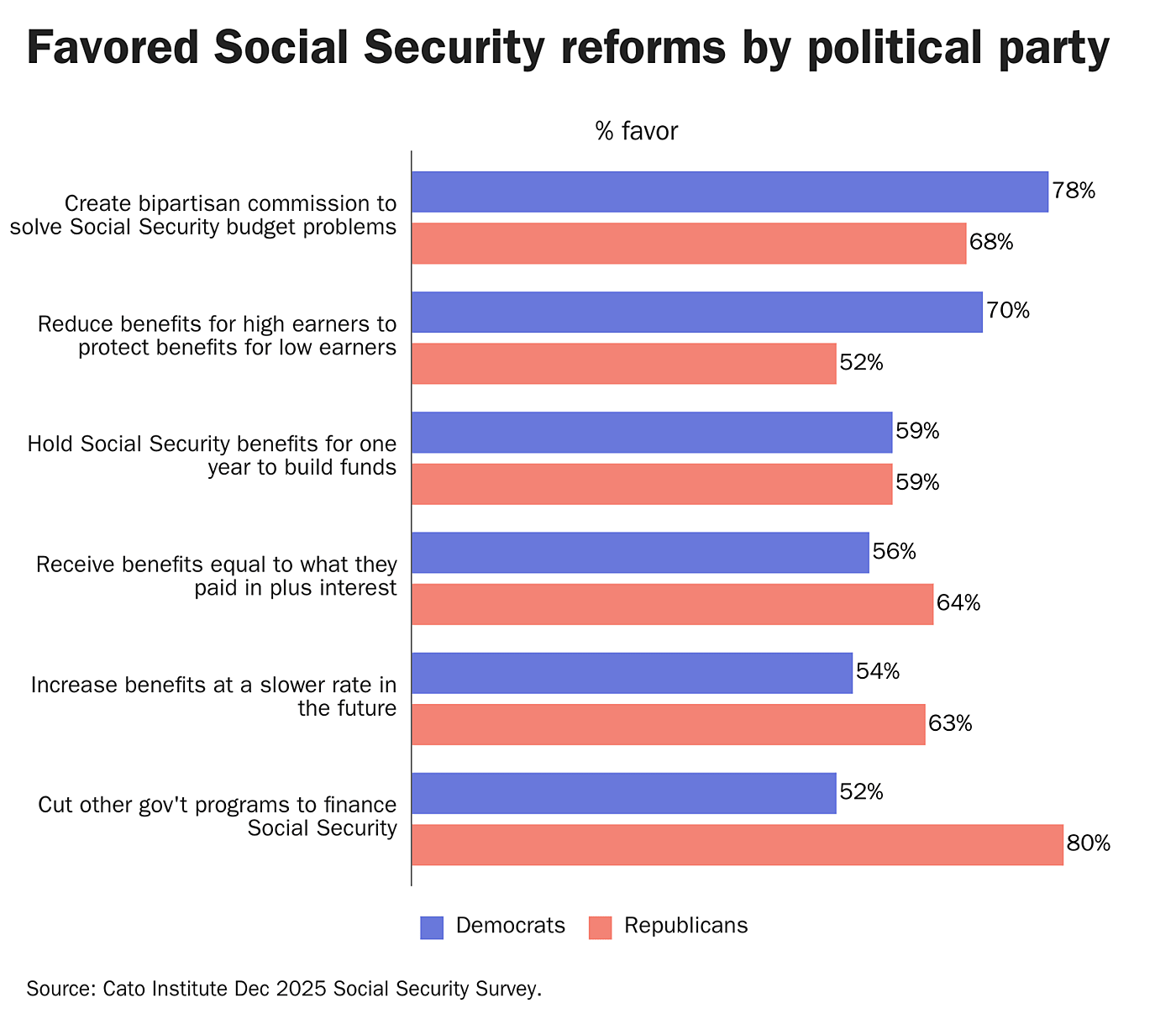

Respondents were asked about a variety of large and small proposals aimed at addressing the Social Security program’s financial problems. The public tends to support small, targeted changes that will not fundamentally address the system’s underlying structural problems—with one potential exception. A majority (71%) would support creating a national commission of bipartisan and independent experts authorized to tackle the program’s financial problems. This type of commission would be similar to the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Commission tasked by Congress in the 1990s with recommending how to close and consolidate military bases. This independent commission avoided the conventional contentious and controversial political processes of shutting down military installations. The public appears to support something similar to handle the fraught issues of reforming Social Security.

Other, smaller reforms the public would support include cutting other government programs to maintain Social Security (64% support). While the public opposes (67%) only paying seniors in financial need, Americans are open to reducing the benefits of higher earners (61%) and cutting benefits that exceed what workers and their employers paid into the system (59%). Americans would also accept slowing the pace at which benefits increase each year (58%) and even freezing cost-of-living increases for one year to build up funds (57%).

Majorities of both Democrats and Republicans support each of these reforms but to varying degrees. Democrats are nearly 20 points more likely than Republicans are to support cutting benefits for higher earners to protect benefits of lower earners (70% vs. 52%). Yet, Republicans are nearly 30 points more likely than Democrats are to support cutting government spending on other programs to finance Social Security (80% vs. 52%). Republicans are slightly more likely than Democrats are to favor increasing benefits at a slower rate (63% vs. 54%) and paying benefits in proportion to contributions (64% vs. 56%). Democrats are slightly more likely than Republicans are to favor a bipartisan commission to solve Social Security’s budget problems (78% vs. 68%).

Overall, the broadest bipartisan support emerges for establishing a BRAC-style commission and for slowing or temporarily freezing benefit growth. Bipartisan agreement weakens if reforms involve cutting other government programs or means-testing the program.

Reforms Americans say they would oppose

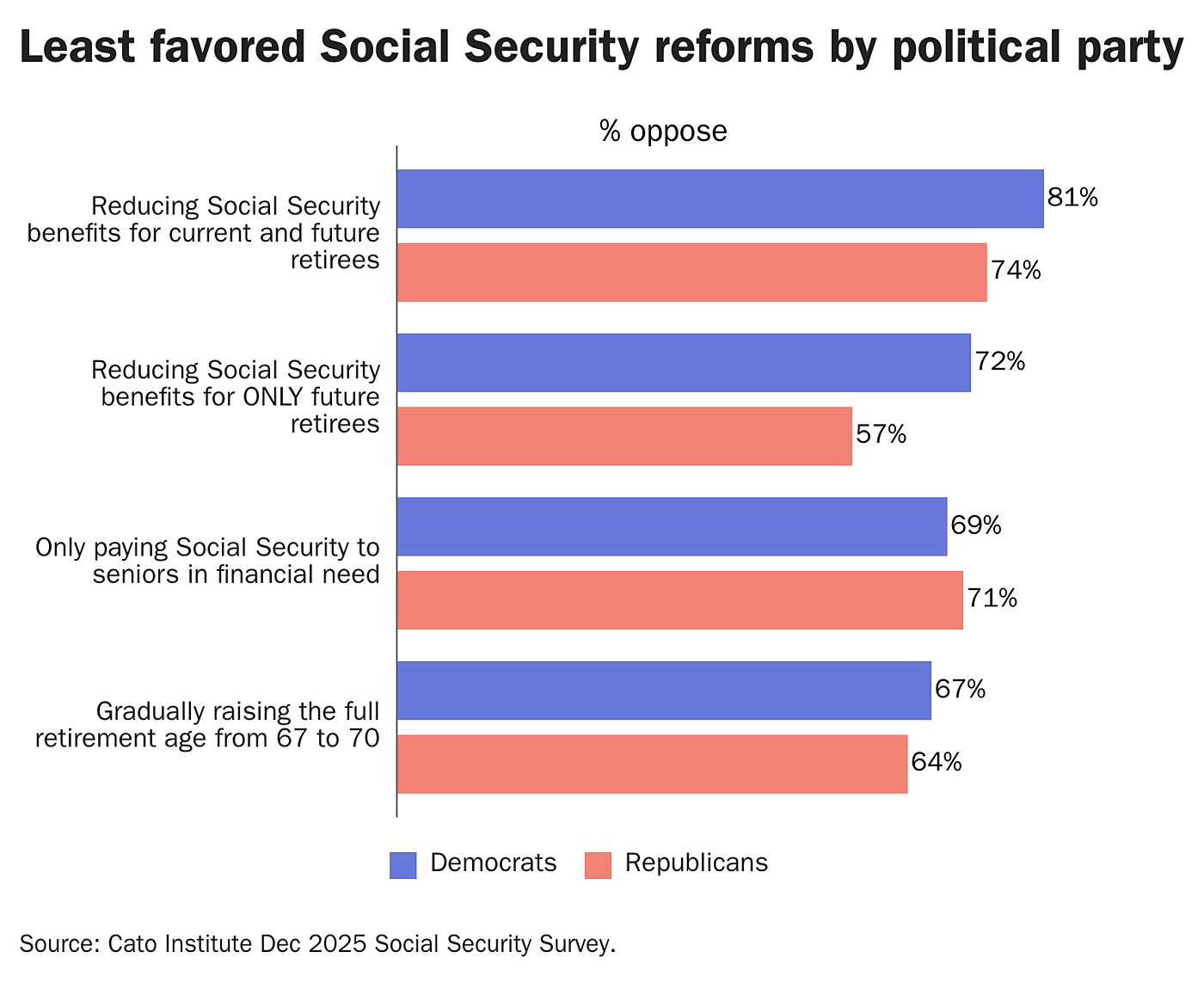

The public opposes the major reforms that would most directly address Social Security’s financial shortfall. Broad-based benefit cuts either for current (77% opposed) or only for future retirees (67% opposed) are deeply unpopular. A similar share (67%) rejects moving Social Security to an anti-poverty, means-tested benefit structure. And nearly two-thirds (65%) oppose gradually raising the retirement age from 67 to 70. Together, these results show that the reforms with the greatest budgetary impact are also some of the most politically fraught.

Partisans are generally equally opposed to these proposals. For instance, similar majorities of both Democrats and Republicans oppose gradually raising the retirement age to 70 (67% vs. 64%) and only paying seniors in financial need (69% vs. 71%). Democrats are more opposed than Republicans to reducing benefits for current and future retirees (81% vs. 74%) or only future retirees (72% vs. 57%).

Younger Americans are much more supportive than older Americans are of benefit cuts. For instance, Americans under age 30 are eight times more likely than seniors are to support immediate benefit cuts (47% vs. 6%). And Gen Z is the only age cohort in which a majority support reducing future benefits (53%) compared to a little more than a third (36%) of seniors and even less (27%) among those between ages 30 and 64.

Public opposition to benefit cuts likely reflects several overlapping beliefs and expectations. As the survey found, many Americans view Social Security as an enforced retirement savings program that they personally paid for (60%); therefore, they see benefit reductions as taking away something they have earned. Others have come to view Social Security as a predictable baseline of income in old age, making them reluctant to disrupt long-standing expectations (65% of retirees say it’s their main source of income). Thus, retirees are far more likely to support taxing younger workers more to maintain benefit levels even if those workers didn’t personally benefit from the tax hikes. Some also believe seniors deserve additional support because of age, past work, or reduced earning capacity. Behavioral dynamics such as loss aversion further amplify this resistance: People are more concerned about losing promised benefits than they are about paying more in taxes.[4]

These reasons are distinct, and breaking them apart is useful. Each implies different strategies for making reforms more acceptable. For example, proposals that guarantee benefits will not fall below a workers’ lifetime contributions plus interest might address concerns about fairness. Likewise, reforms that offer a flat universal benefit could resonate with those who see Social Security as a minimum income guarantee. Understanding the specific sources of opposition enables policymakers to design reforms that directly address public concerns, making otherwise difficult changes more politically feasible.

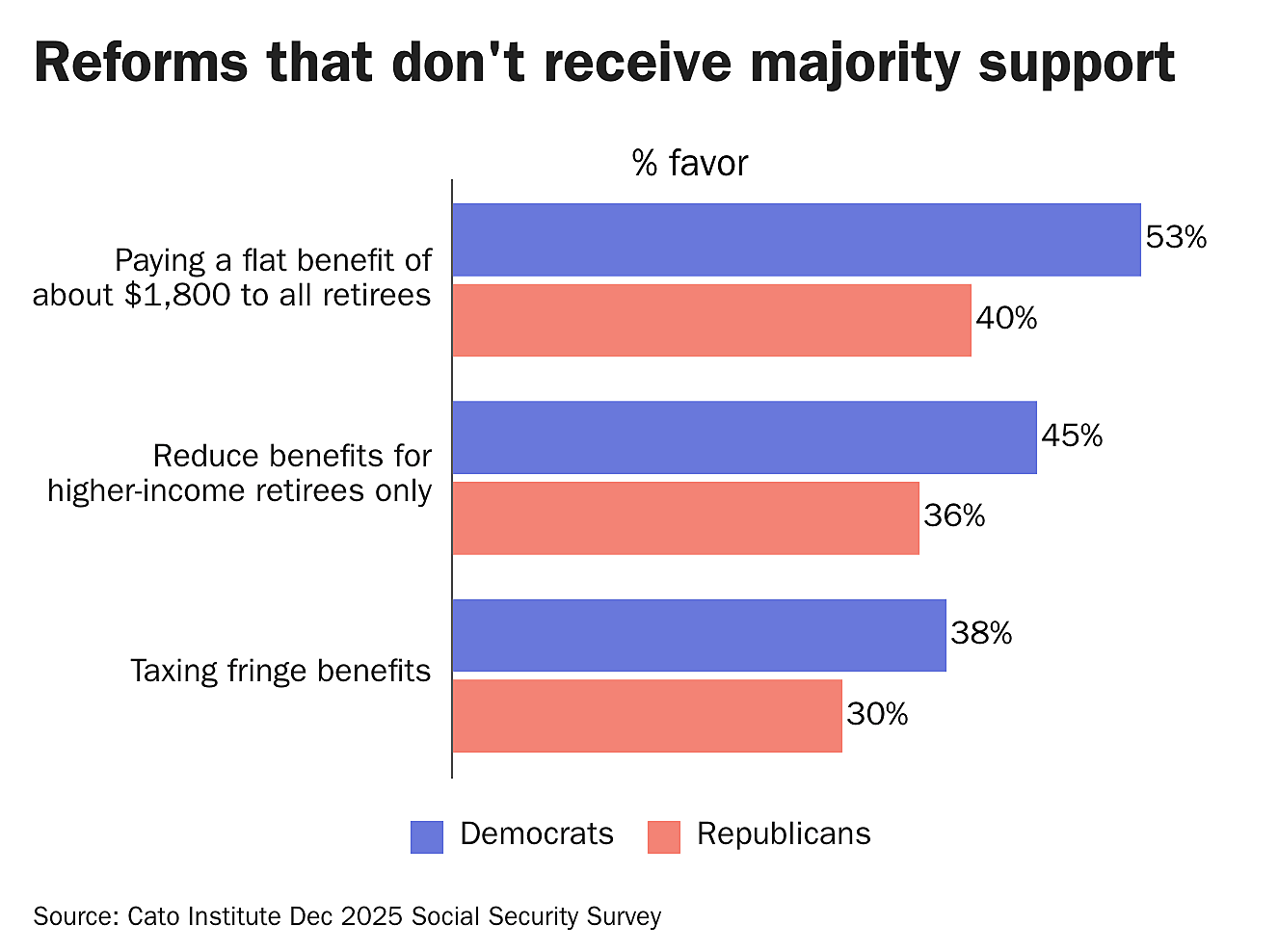

Reforms with mixed support

The public is ambivalent about other reform options. For instance, a third (31%) would support but a plurality (47%) would oppose taxing employer-provided fringe benefits such as health insurance. A plurality (41%) would support reducing higher earners’ benefits to protect lower earners’ benefits and avoid tax increases, while 29% would oppose since higher earners paid more into the system. Nearly a third (30%) aren’t sure either way.

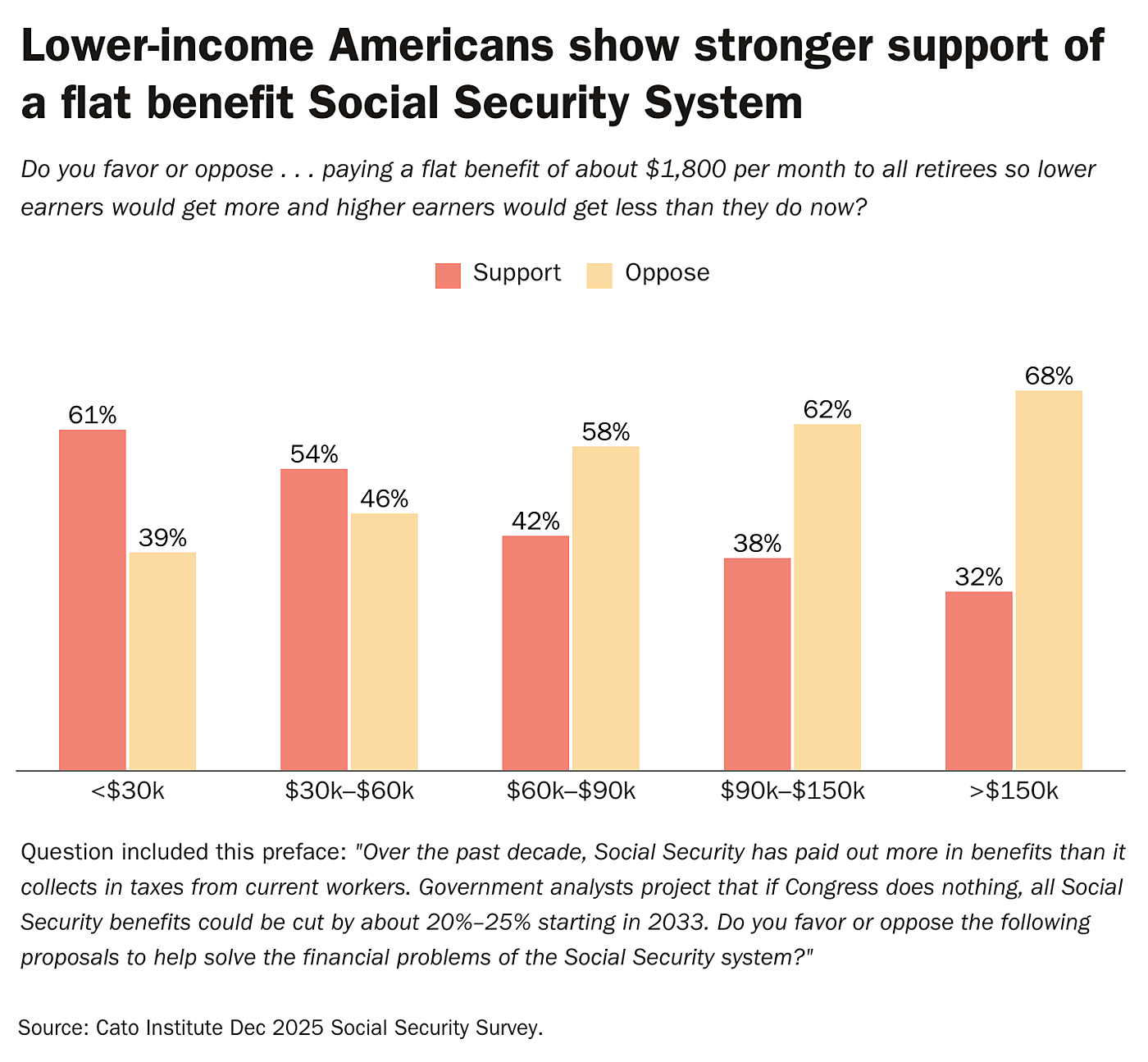

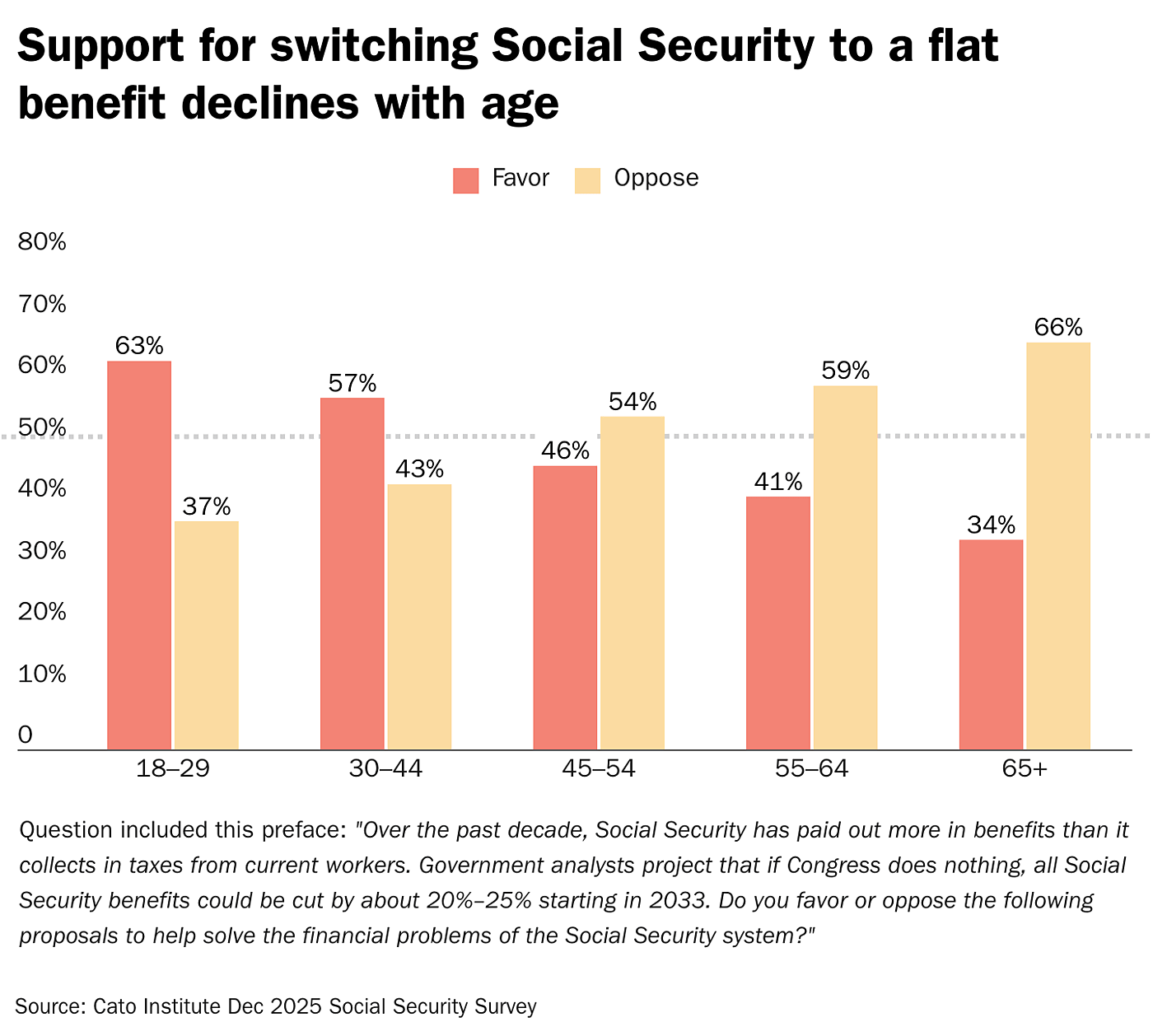

Would Americans support a flat benefit?

Some analysts have proposed adopting a flat universal benefit—a single uniform monthly payment for all retirees—–to avoid large tax increases or across-the-board benefit cuts. When framed explicitly as an alternative to these broader sacrifices, a plurality (38%) of Americans support “changing social security so that all retirees get the same flat monthly benefit of about $1,800 per month—even if that means lower benefits for high earners and higher benefits for low earners.” About a quarter (28%) would oppose the idea, while a third (34%) are unsure. Support falls when the flat benefit is presented without the trade-off context. In this neutral framing, a plurality (35%) oppose the reform, compared to 32% who support it and 33% who are unsure.[5]

Support shifts when the policy is framed as a way to address Social Security’s financial problems—and respondents are required to choose a side. Under this framing, a slim majority (52%) oppose paying a flat benefit of $1,800 per month to all retirees, while 48% support it. Partisans diverge with a majority of Democrats (53%) who support the flat benefit and a solid majority of Republicans (60%) who oppose it. Current Social Security recipients are more likely to oppose (56%) a flat benefit than non-recipients (49%) are. One reason may be that the amount is less than what most are currently receiving or expect to receive.

Support also varies by income. Majorities of lower-income Americans support a flat benefit—61% among those earning under $30,000 annually and 54% among those earning $30,000 to $60,000 annually. But support declines as income rises: Majorities oppose the flat benefit among those earning $60,000–$90,000 annually (58% opposed), $90,000–$150,000 annually (62% opposed), and more than $150,000 annually (68% opposed). Notably, a majority of middle-income earners (58%) feel they would lose out under this reform.

This pattern is consistent with the broader survey finding that most Americans view Social Security as a contributory retirement program in which they think benefits should be proportional to what workers paid in. A flat benefit conflicts with proportionality, making it more appealing to lower-income earners but less acceptable to middle- and higher-income Americans and current beneficiaries.

Would Americans support means-testing Social Security?

The survey finds limited support for means-testing Social Security and a preference for benefits to be proportional to contributions. Most Americans (58%) think Social Security ought to “pay benefits in line with what each worker contributed,” while less than a quarter (23%) think that lower earners should receive relatively more and higher earners receive relatively less. Another 19% are unsure.

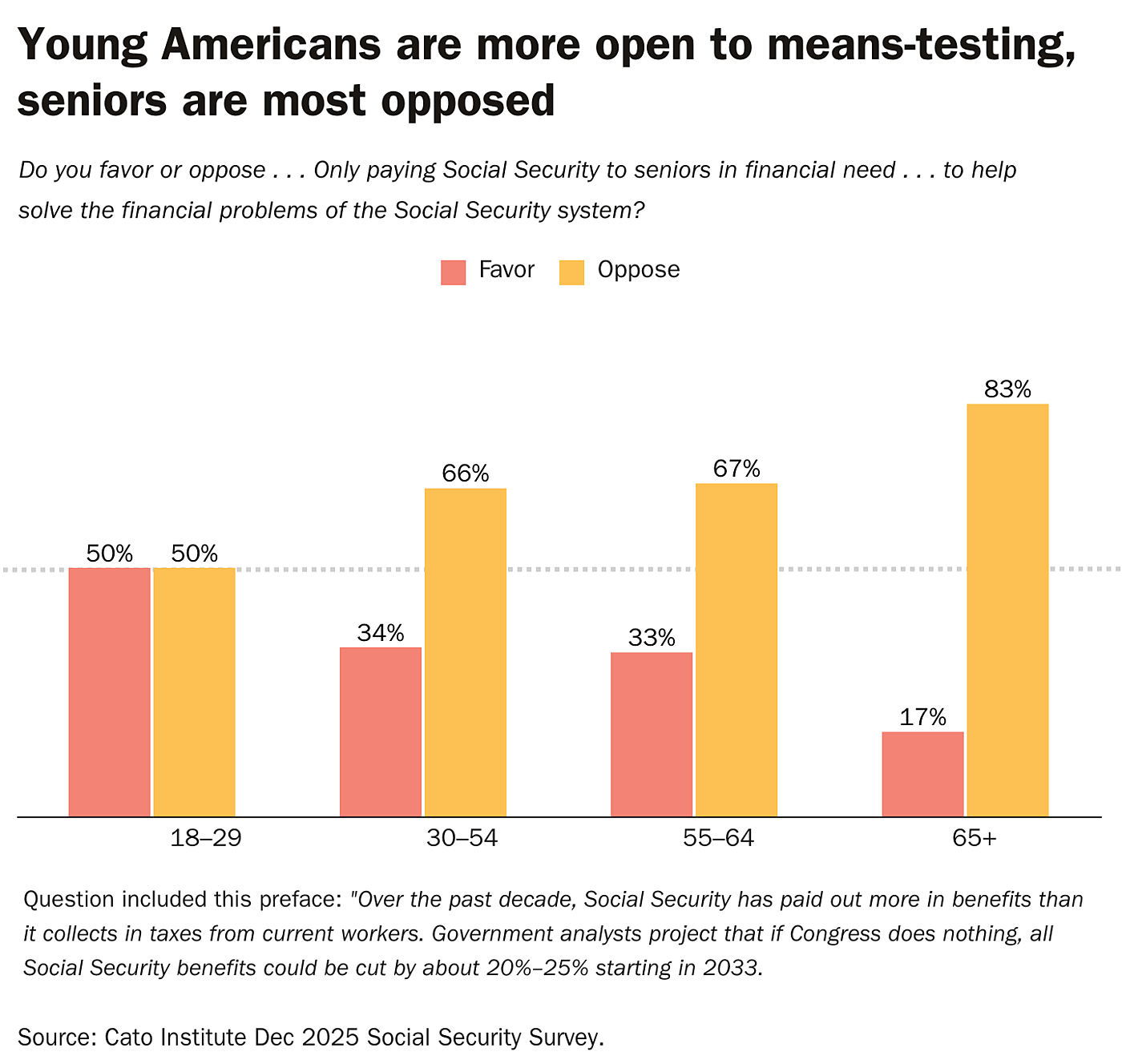

When confronted with the trade-offs, such as across-the-board benefit cuts or tax increases, attitudes shift only modestly. Most are averse to a complete elimination of benefits for higher income earners. Only 33% would support providing benefits only to “seniors in financial need” as a way to address Social Security’s financial shortfall, and 67% would oppose it.

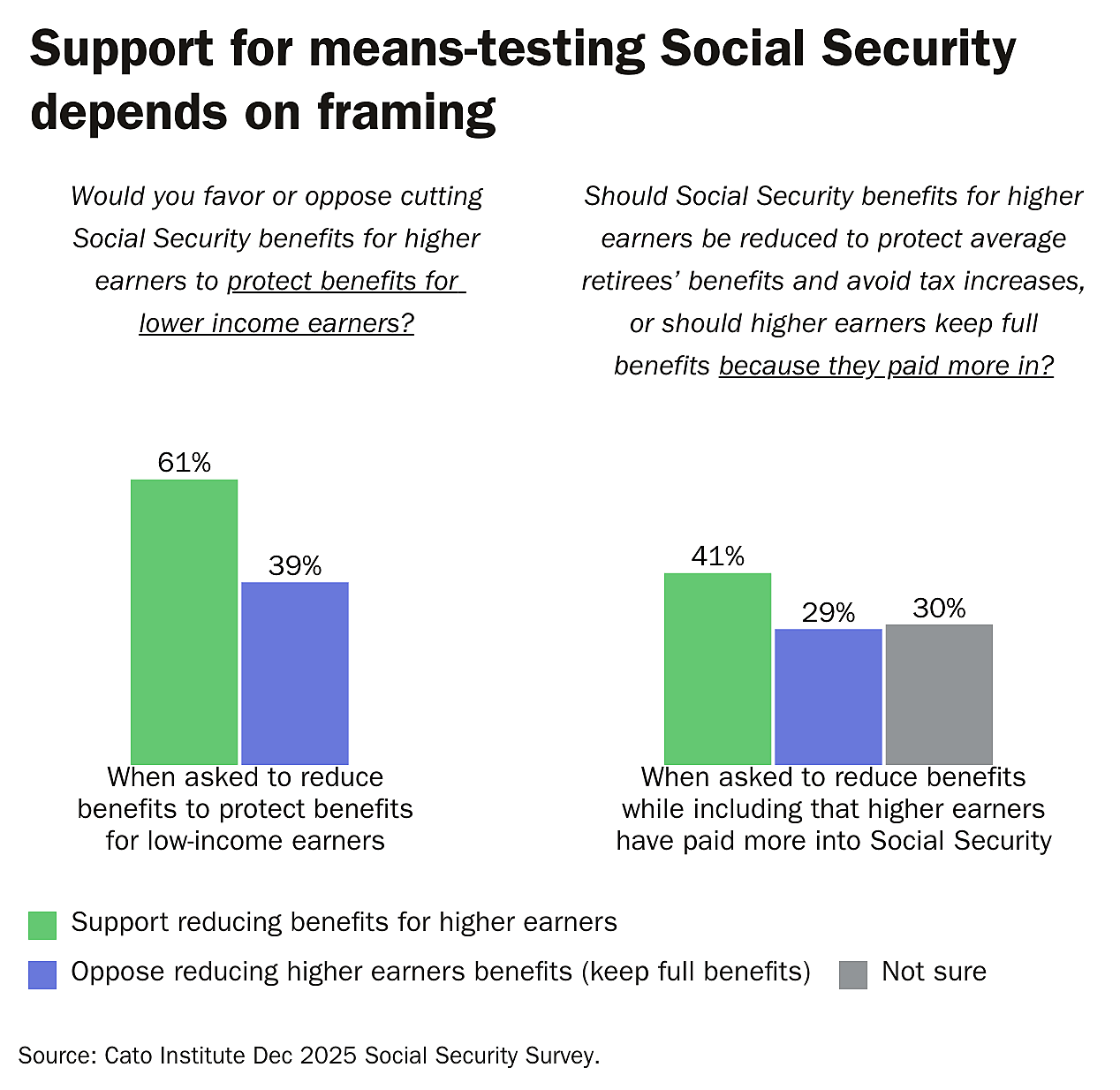

Support increases somewhat when reforms are framed as reducing, rather than eliminating, benefits for high earners. If framed as reducing benefits for high earners to “protect benefits for low-income earners” a solid majority (61%) favor and 39% oppose the approach. However, when the same approach is framed to mention that higher earners paid more in, support drops to less than half (41%) who support reducing higher earners’ benefits to protect lower earners’ benefits, while 29% think higher earners should “keep full benefits because they paid more in.” Nearly a third (30%) aren’t sure.

Overall, these results indicate limited enthusiasm for means-testing but greater openness to targeted reductions for higher earners when framed as protecting low-income retirees. Even then, public support is constrained by a strong underlying belief that Social Security should operate as a retirement savings program in which workers receive benefits roughly proportional to what they contributed.

Reform package

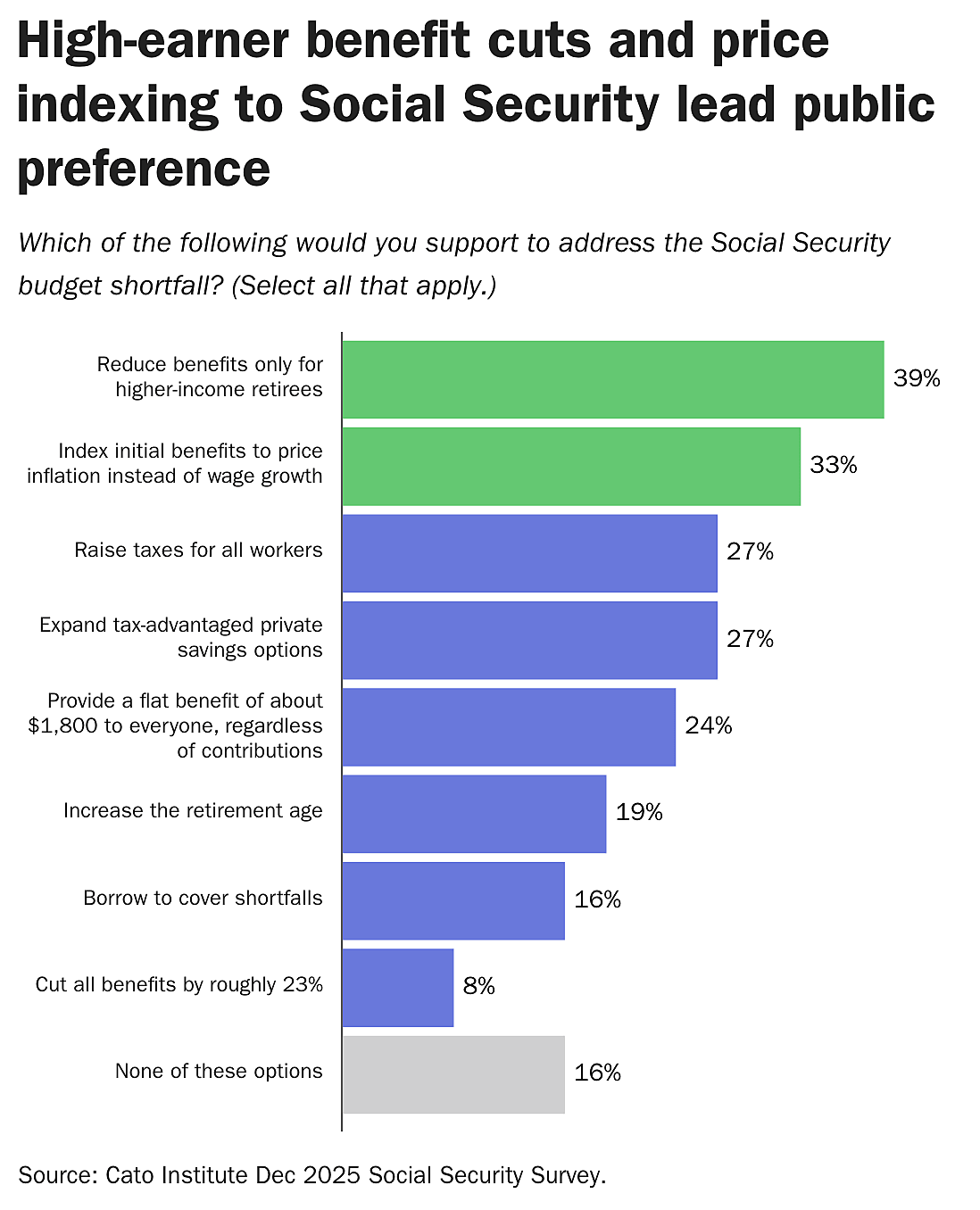

Solving Social Security’s budget crisis will likely require a multifaceted approach. The survey offered respondents as many reform options as they wished from a list of eight proposals. No single reform option reached majority support.

- Reducing benefits for higher-income retirees (39%)

- Adjust initial benefits to rise with price inflation rather than wage growth (33%)

- Raise taxes across the board (27%)

- Expand private tax-preferred savings options (27%)

- Offer a flat benefit of about $1,800 a month to all, regardless of contributions (24%)

- Raising the retirement age (19%)

- Borrowing money (16%)

- Across-the-board benefit cuts of about a quarter (8%)

Another 16% said they opposed all eight options. The absence of majority support for any of these reforms underscores why a BRAC-style bipartisan national commission will likely be important to assemble a politically viable assortment of necessary changes.

Generational Divide on Social Security

The survey found significant generational divides in how Americans think about Social Security and its reform, particularly between current retirees and younger workers. This is important given Social Security’s pay-as-you-go structure in which younger workers pay for older retirees’ benefits. The survey revealed that young Americans are the least likely to expect Social Security will exist for them, the most open to reforms, and the least likely to understand how the program works.

Gen Z isn’t confident Social Security will exist for them

Only about a third (34%) of Americans under age 30, referred to as Gen Z in this report, think Social Security will exist when they retire. Gen Z also expects significant benefit cuts, nearly eight in 10 (78%) expect to receive less than the full scheduled benefit, compared to 56% among current retirees who expect a benefit cut.

Gen Z views Social Security as an anti-poverty program

Younger Americans’ conception of Social Security is more aligned with what its architects intended: an anti-poverty program. While a majority (55%) of Americans and seniors specifically (60%) say the purpose of Social Security is primarily to replace seniors’ incomes after they retire, a slim majority (52%) of Gen Z think its purpose is “to ensure no seniors fall below the poverty line.”[6] Although a plurality (49%) of young Americans think of Social Security as a retirement savings program, they are more than twice as likely as seniors to think of it as a “welfare program that provides benefits” (33% vs. 14%).

Gen Z doesn’t know how Social Security works

Gen Z is also the most misinformed about how Social Security works. For instance, half (50%) of Gen Z thinks their Social Security taxes are saved for them either in a personal account or “invested” in the Social Security Trust Fund. Less than a third (29%) understand their taxes pay for current retirees. Conversely, only 19% of seniors think their money is waiting for them in a personal account (3%) or “invested” in the Social Security Trust Fund (16%). Gen Z is also much less likely than seniors are to know when Americans can first start collecting benefits (80% vs. 32% didn’t know the right answer).

Gen Z is most likely to support reform and benefit cuts

Taxes: Initially, Americans under age 30 are about as likely as older Americans to support increasing taxes to maintain Social Security benefits. For instance, 61% of Gen Z and 64% of seniors say they support raising payroll taxes from 12.4% to 16.05% to close the budget shortfall. But younger Americans turn against raising payroll taxes to maintain benefit levels “if current workers would eventually get back less than they paid in.” If this were to occur, 60% of Gen Z would oppose, while 52% of seniors would favor the tax hikes.

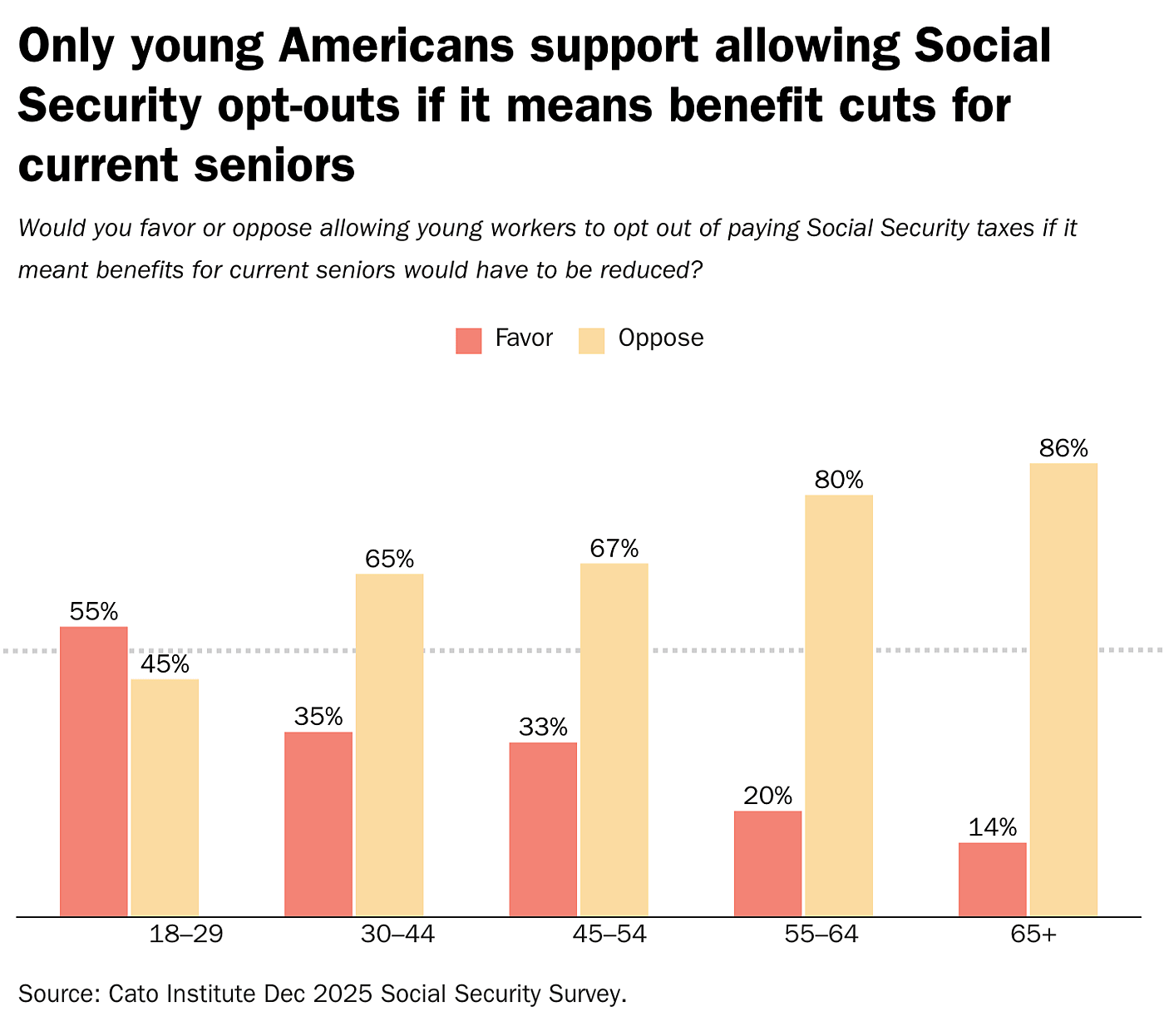

Solving Social Security’s financial problems will require trade-offs, and so the survey asked about the trade-off between taxing younger workers and maintaining benefit levels for current seniors. When asked to choose, Gen Z is the only cohort that prefers cutting benefits for current retirees to protect younger workers from higher taxes (53%). In contrast, majorities of 30–44 year olds (57%) and even more 45–54 year olds (74%), 55–64 year olds (84%), and those age 65 and over (89%) say current retiree benefits should be protected even if that means higher taxes on younger workers.

Benefit cuts: Younger Americans are nearly eight times more likely than seniors are to support benefit cuts to help solve the financial problems in the Social Security system. Nearly half (47%) of Americans under age 30 support benefit cuts compared to about a quarter (26%) of those 30–54 years old, 10% of those 55–64 years old, and 6% of those over 65 years old.

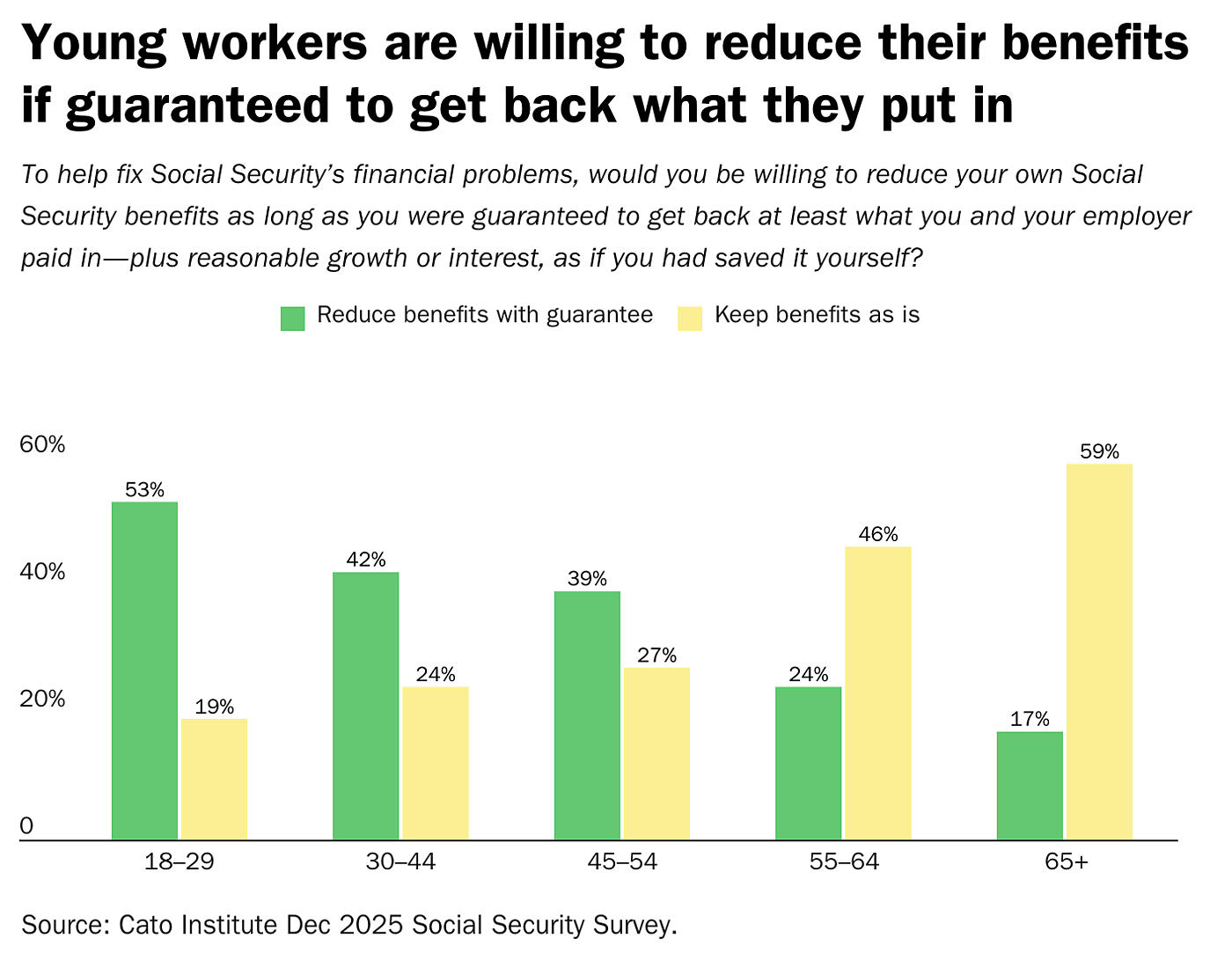

Having paid far less into the system, younger Americans are significantly more likely than older cohorts are to accept reducing their own benefits as long as they are “guaranteed to get back at least what [they and their] employer paid in—plus reasonable growth or interest.” A majority (53%) of Americans under age 30 would support reduced benefits with this guarantee, as would pluralities of 30–44 year olds (42%) and 45–54 year olds (39%). However, a plurality (46%) of 55–64 year olds and a solid majority of seniors (59%) would not accept benefit cuts even with the guarantee to keep benefits proportional to contributions.

Means-testing Social Security

Young Americans are more supportive of means-testing Social Security than older cohorts are. Half (50%) of Americans under age 30 support only paying Social Security to seniors in financial need compared to 17% of those over age 65 and about a third of those 30–64 years old.

Flat benefits

Majorities of Americans under age 45 support the idea of Social Security paying a flat benefit to all retirees of about $1,800 per month, whereas older Americans oppose. Majorities of Americans under age 30 (63%) and 30–44 year olds (57%) favor paying a flat benefit to all retirees regardless of contributions. In contrast, majorities of 45–54 year olds (54%), 55–64 year olds (59%), and those over age 65 (66%) oppose shifting Social Security to a flat benefit.

Opting out

Allowing younger workers to put part of their Social Security taxes into personal investment accounts is appealing to Americans, garnering 60% support. However, this is logistically difficult given the program’s pay-as-you-go structure in which younger workers pay the benefits of current retirees. When people learn that allowing younger workers to opt out of paying Social Security taxes meant benefit cuts for current seniors, attitudes flip and a majority oppose (69%) except among Gen Z. Among those under age 30, 55% would support allowing younger workers to opt out of paying Social Security taxes even if it meant benefit cuts for seniors. Conversely, majorities of 30–44 year olds (65%), 45–54 year olds (67%), 55–64 year olds (80%), and 65 year olds (86%) all solidly oppose opt-outs if it required benefit cuts.

Gen Z, which shoulders a growing share of the Social Security program’s financing, are the least confident that the system will exist for them, the least informed about its mechanics, and the most open to structural reforms including benefit cuts, means-testing, and flat benefits. This reflects a fundamentally different conception of Social Security—one closer to an anti-poverty floor than the current earnings-based structure. If Gen Z’s views don’t follow the path of older cohorts, there may be potential for new reform coalitions as this generation matures into high-turnout voters. But also, the generation’s openness to reform could be at least partly rooted in misunderstandings of the program and its mechanics, indicating that increased knowledge of the program could meaningfully shift attitudes.

The survey suggests that Social Security may function politically as many intergenerational transfer programs: It relies heavily on younger workers who also happen to be the most misinformed about how the system operates and least likely to vote. This creates a dynamic in which younger cohorts—which are financing retirees’ benefits—lack the information needed to evaluate whether the arrangement is fair or sustainable. In this sense, widespread misunderstanding among younger Americans unintentionally reinforces a system that would face far more political pressure if its mechanics were more widely understood. If younger contributors understood more fully that their taxes fund current retirees, that projected benefits for their own generation may fall short of what they’re paying, and that demographic trends make their cohort’s deal progressively less favorable, tolerance for the system’s current design could erode quickly.

Implications

The survey highlights three major barriers to Social Security reform: widespread public misunderstanding of how the program works, deep structural imbalances that require politically difficult trade-offs, and a mismatch between how Americans believe the system should operate (as a universal, contributory, and proportional retirement program) and how it actually operates (as a pay-as-you-go system with progressive replacement rates). These informational, structural, and normative gaps shape subsequent findings and help explain why reform has remained politically intractable.

Americans overwhelmingly value Social Security but are broadly misinformed about its mechanics, financing, and original purpose. Many do not understand how the program is funded, how benefits are determined, when eligibility begins, or that earlier cohorts contributed very little relative to what they received. Nor are most aware of the dramatic demographic shifts—from 16 workers per retiree in 1950 to 2.7 today—that drive the program’s budget shortfall. These gaps in understanding make it more difficult for policymakers to build support for structural changes.

Public beliefs about what Social Security is further complicate reform. Most Americans view it as a government-enforced personal retirement savings plan rather than as a redistributive social insurance program. They believe benefits should be universal, contributory, and proportional to what each worker paid in. These expectations conflict with the program’s actual design, in which benefits are mildly progressive and are financed by current workers’ payroll taxes.

At the same time, the program is on an unsustainable trajectory, and substantial reforms will be required if Americans want to avoid roughly 25% benefit cuts in the next decade. Although most people recognize that Social Security faces financial challenges, they underestimate the scale of the shortfall and are unfamiliar with its underlying causes.

The public generally supports reform only when changes are framed as the “least bad” option. Americans are more open to incremental adjustments—such as slowing benefit growth or temporarily freezing cost-of-living increases—than to major tax increases or broad benefit cuts. While many initially say they favor raising taxes to preserve benefits, support collapses when increases are presented in realistic dollar amounts or when higher taxes would not guarantee proportional returns for today’s workers.

Americans are uncomfortable transforming Social Security into a strictly means-tested anti-poverty program, yet they are more open to reducing benefits for higher earners to protect lower-income retirees. They are also more accepting of benefit adjustments that preserve the proportionality principle they believe that the program embodies.

In short, Americans want Social Security to remain solvent, but they reject most reforms that would actually close the funding gap, except for delegating authority to an independent, nonpartisan commission to implement solutions.

Until the public has a clearer understanding of how Social Security functions and why it faces fiscal strain, building consensus around realistic and necessary reforms will remain extraordinarily difficult.

Methodology

The results presented in this survey report are drawn from two nationally representative surveys—primarily from the Cato Institute December 2025 Social Security Survey conducted by YouGov, which is an in-depth exploration of Americans attitudes, assumptions, and beliefs about the program, and the Cato Institute August 2025 Social Security Survey, which is a short survey conducted by Morning Consult. Unless otherwise noted, all findings in this report refer to the December 2025 survey with YouGov.

YouGov collected responses online between October 9 and14, 2025, from a national sample of 2,000 Americans 18 years of age and older. Restrictions were put in place to ensure that only the people selected and contacted by YouGov were allowed to participate. The margin of error for the survey is +/- 2.59 percentage points at a 95% level of confidence. A more detailed methodology statement can be found in the topline and crosstab documents. Morning Consult collected responses online between July 19 and 21, 2025, from a nationally representative sample of 2,200 respondents. The survey has a margin of error of +/- 2 percentage points.

Full topline results and methodology for the December survey can be found HERE and crosstabs found HERE. Topline and methodology for the August survey can be found HERE and crosstabs can be found HERE.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.