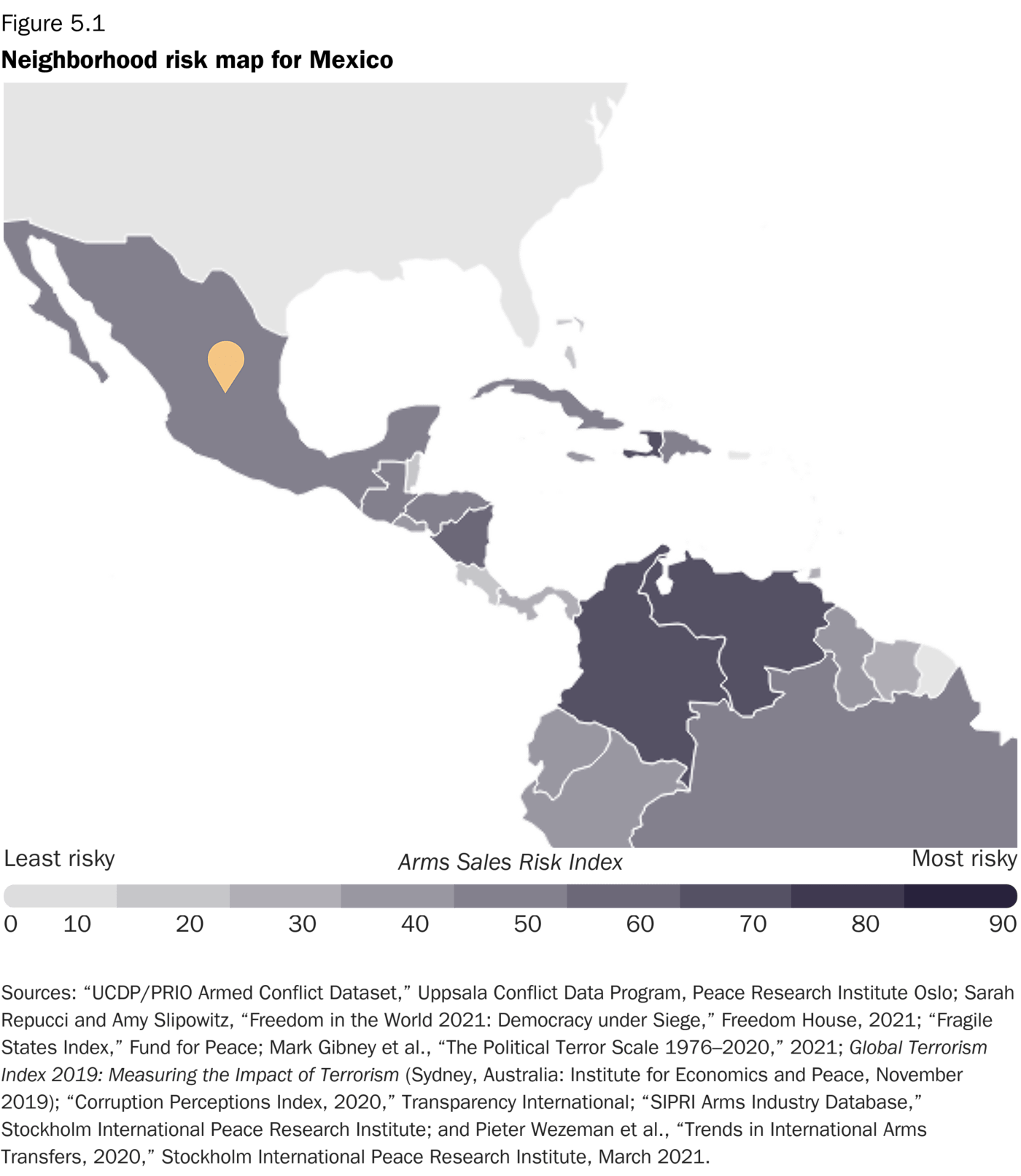

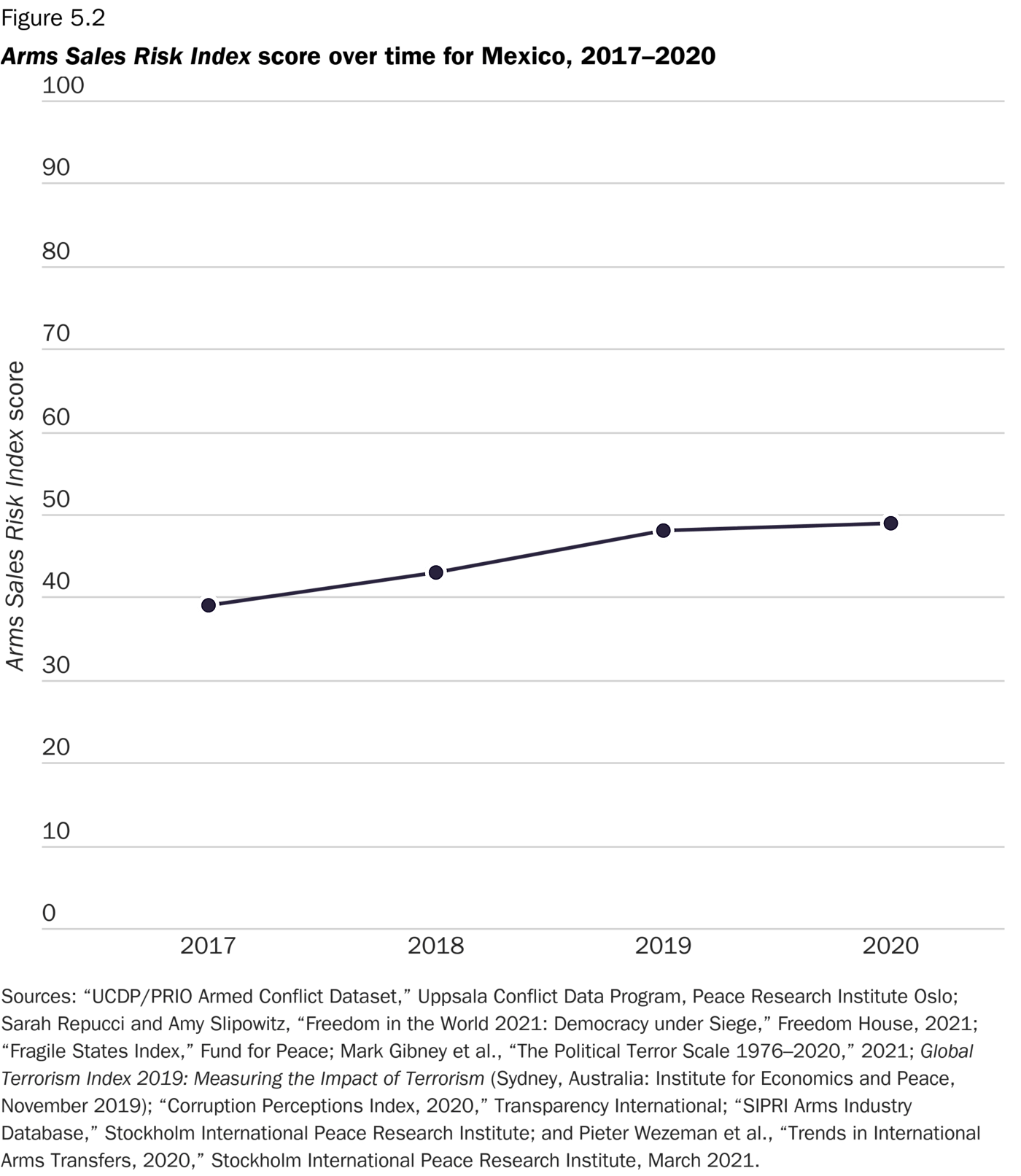

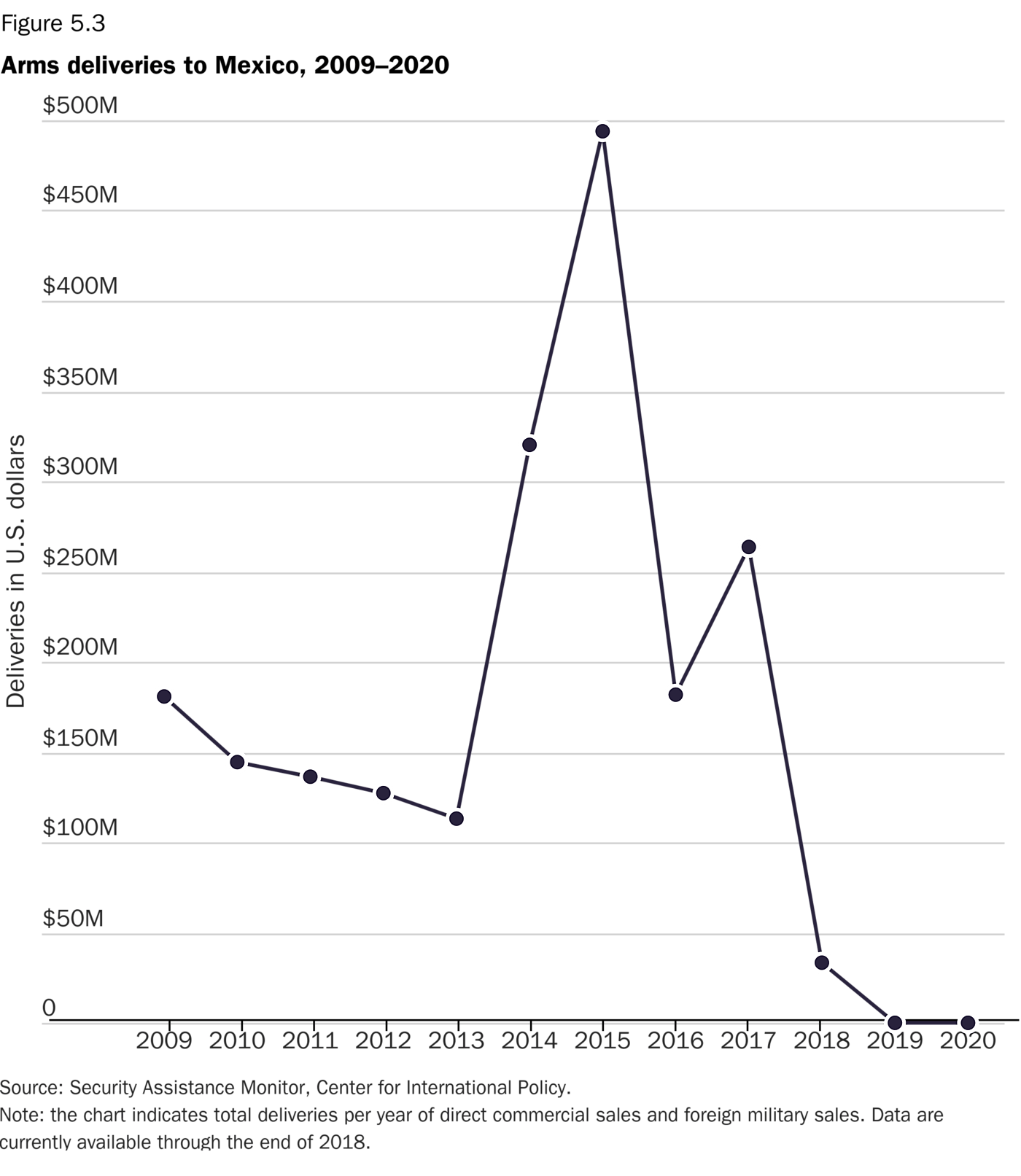

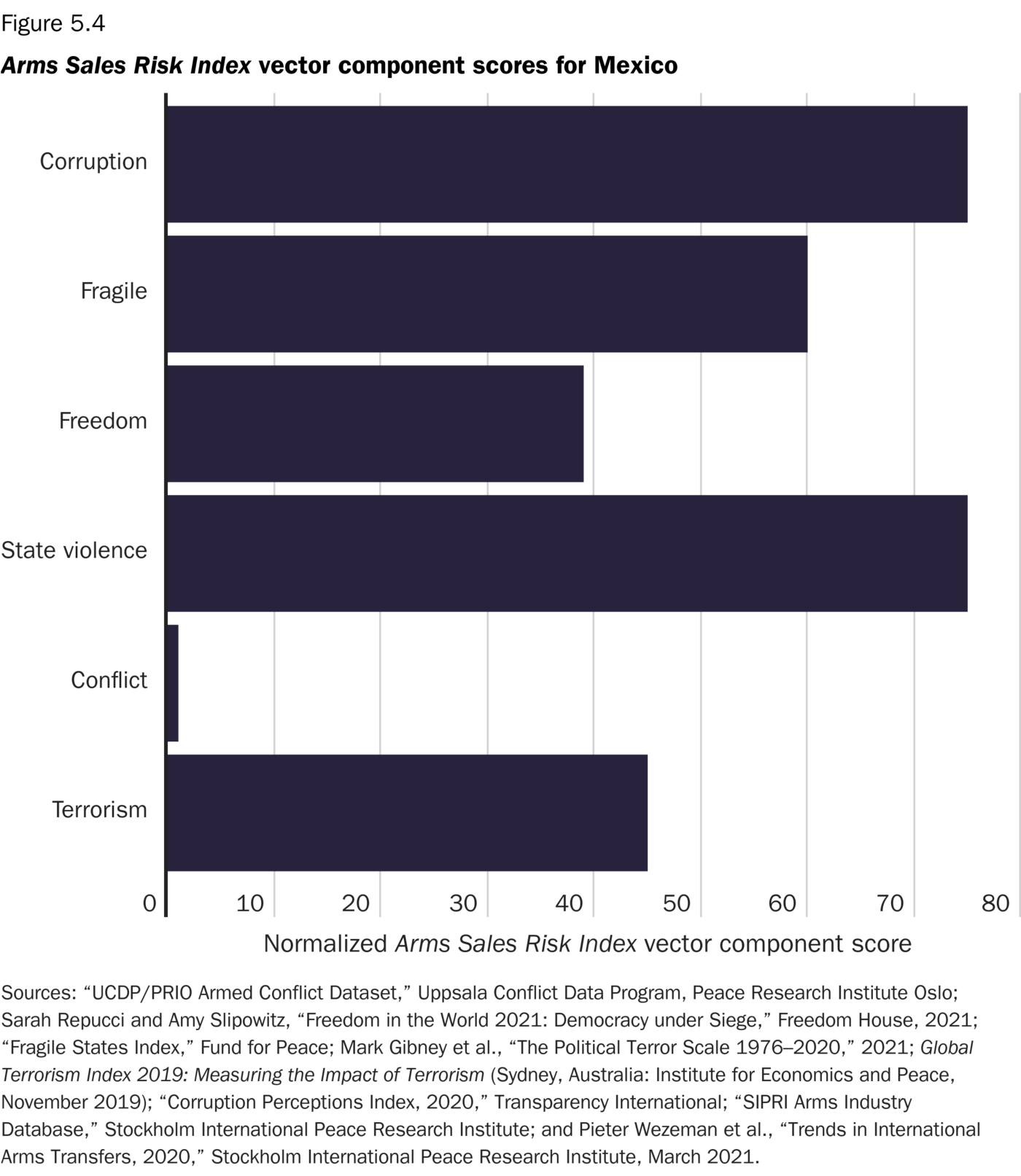

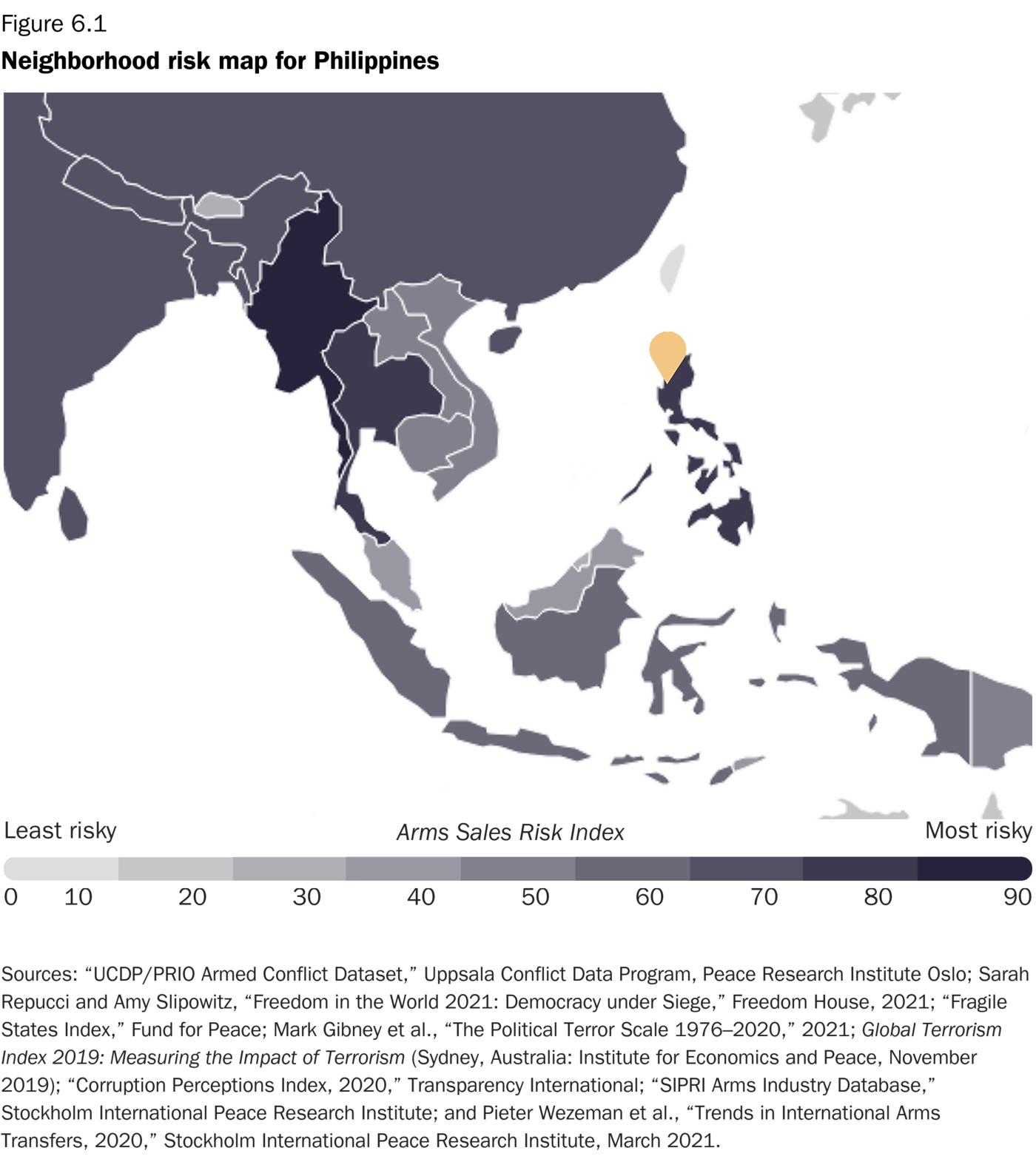

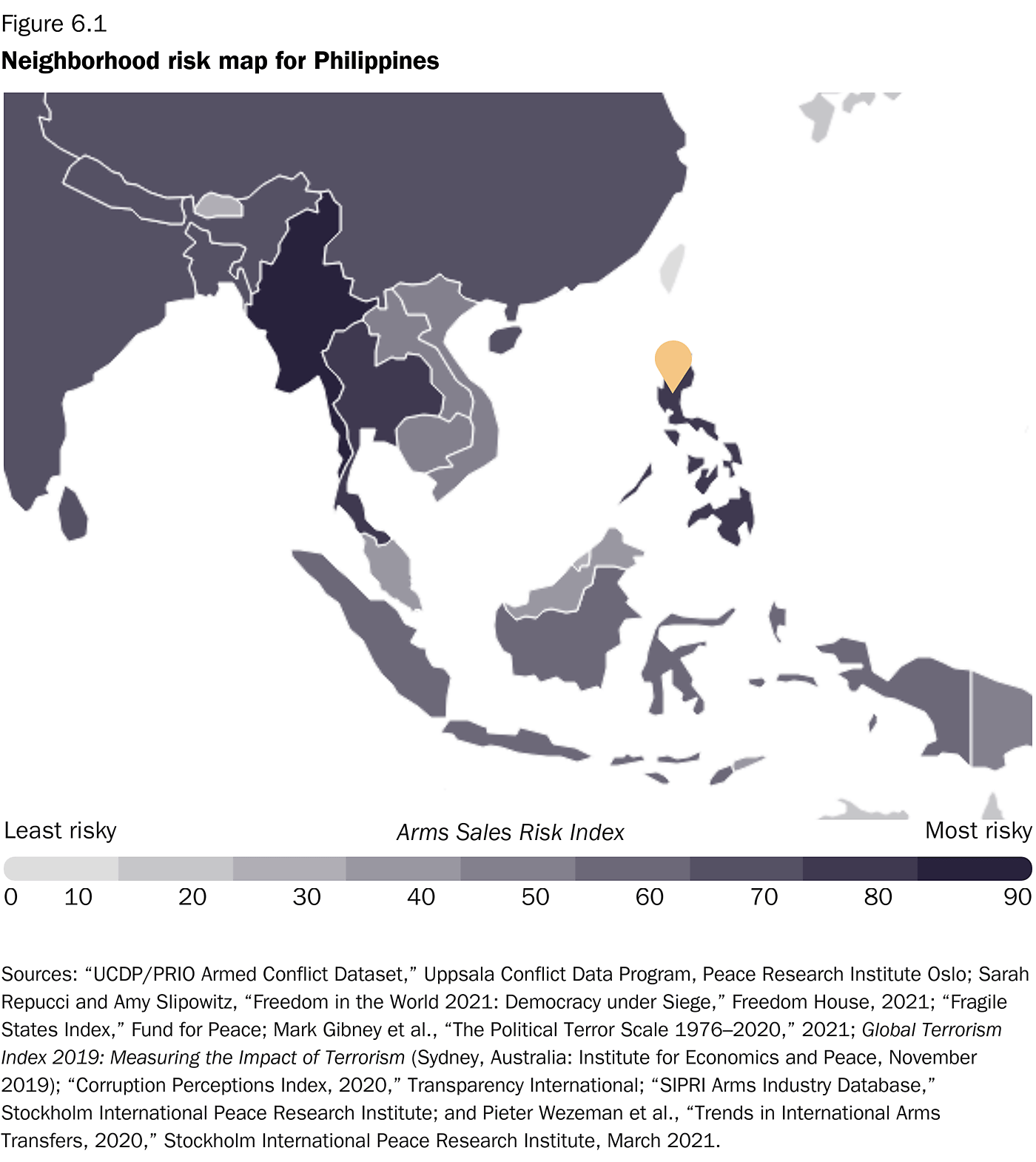

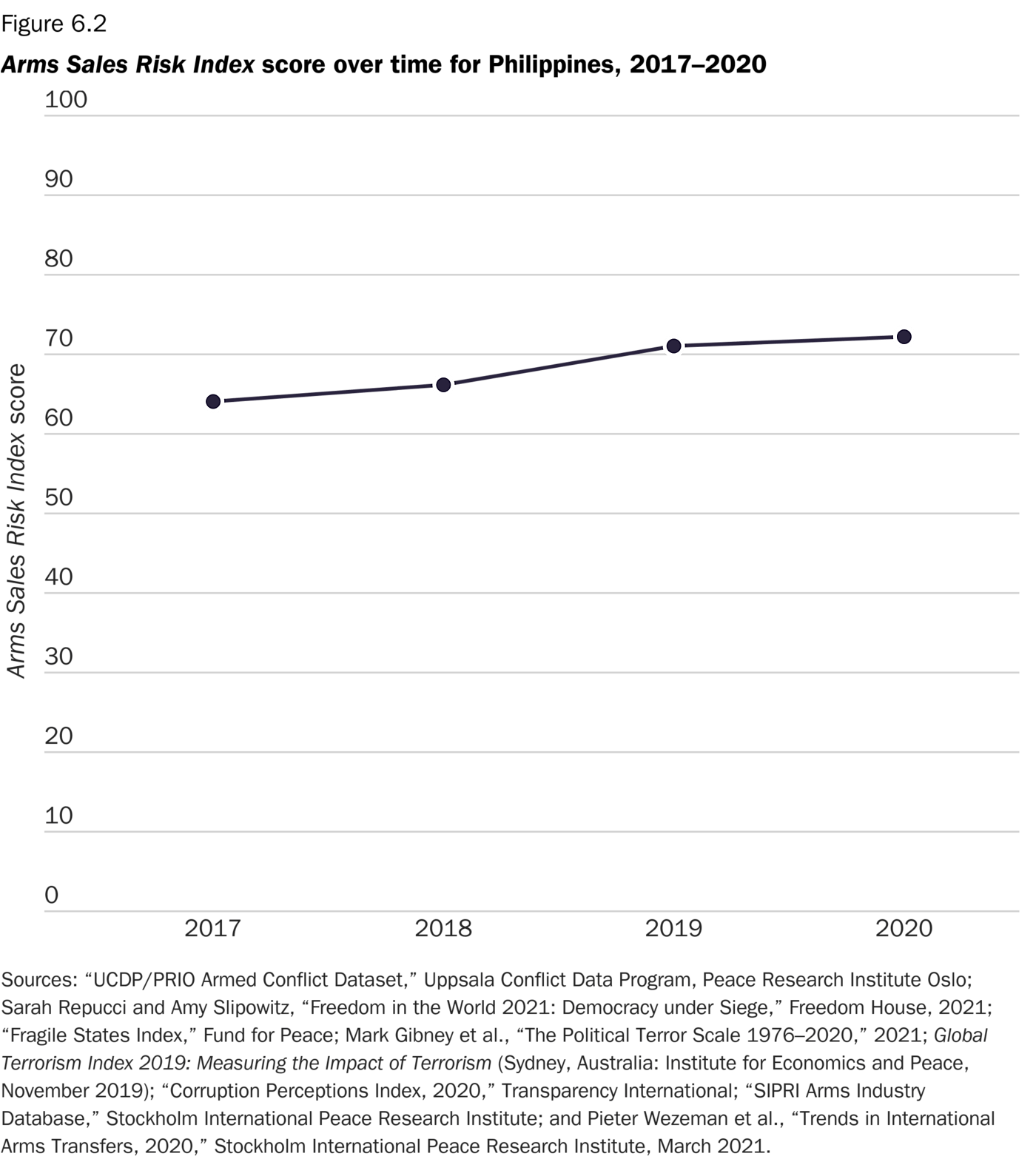

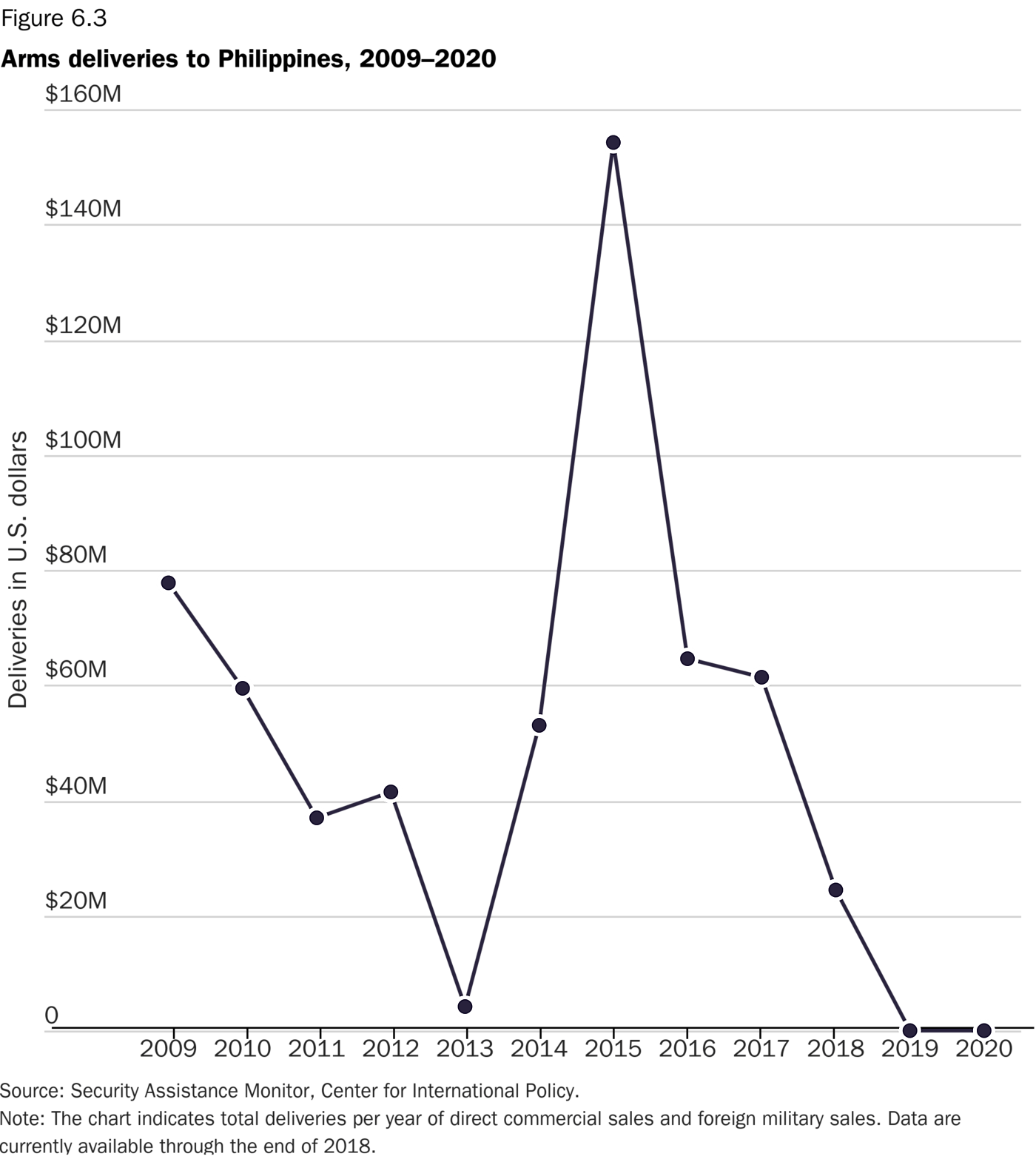

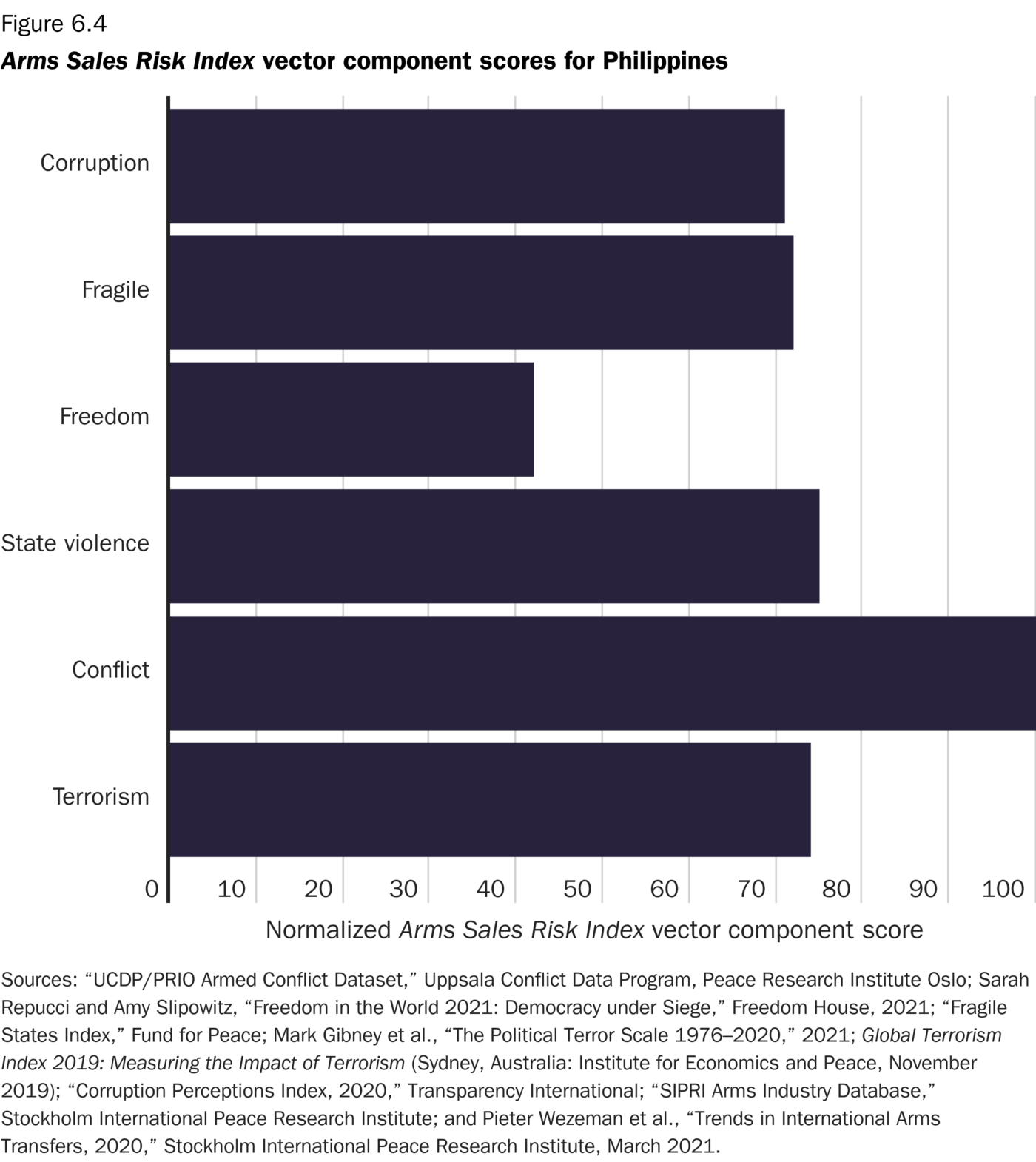

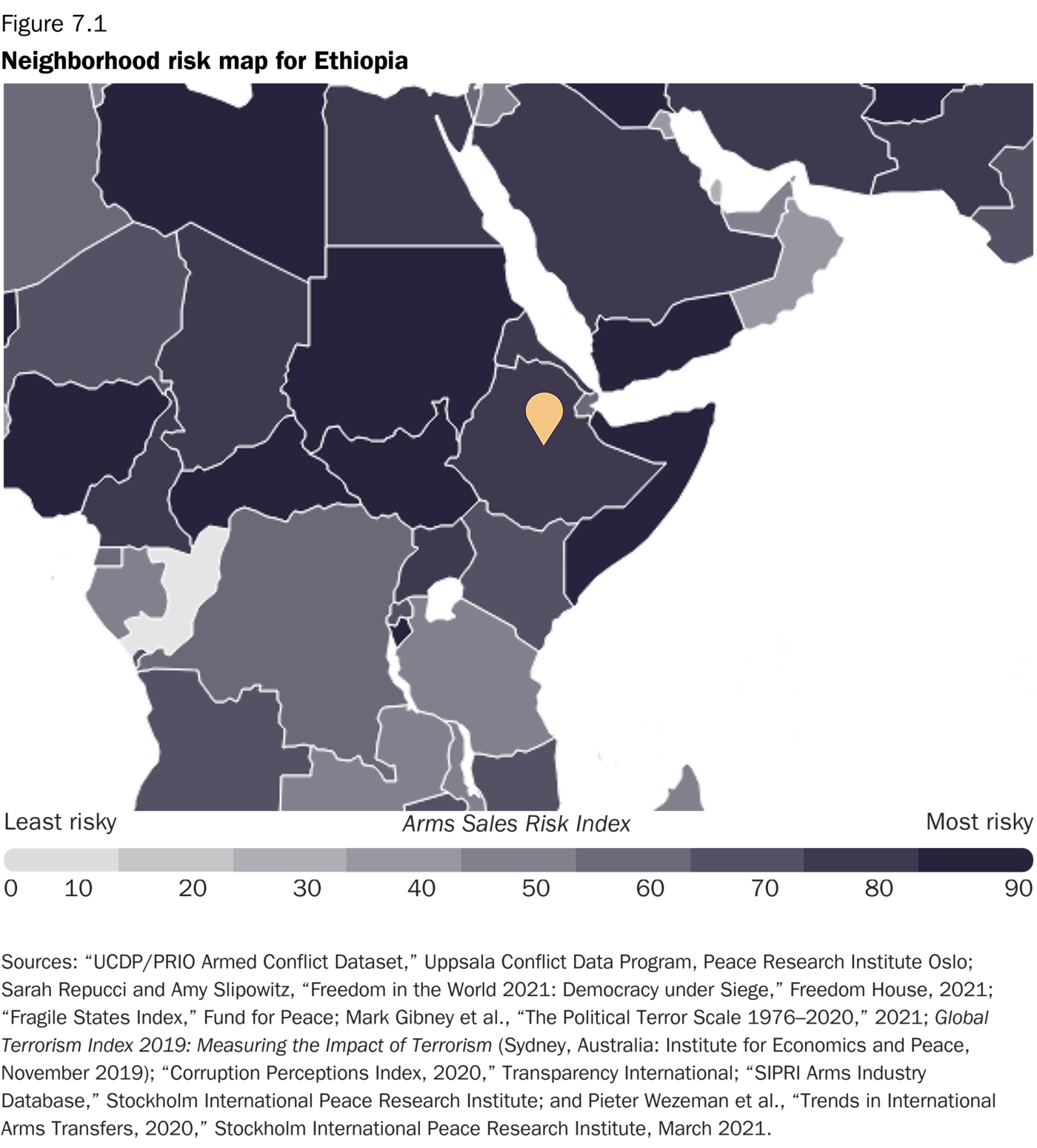

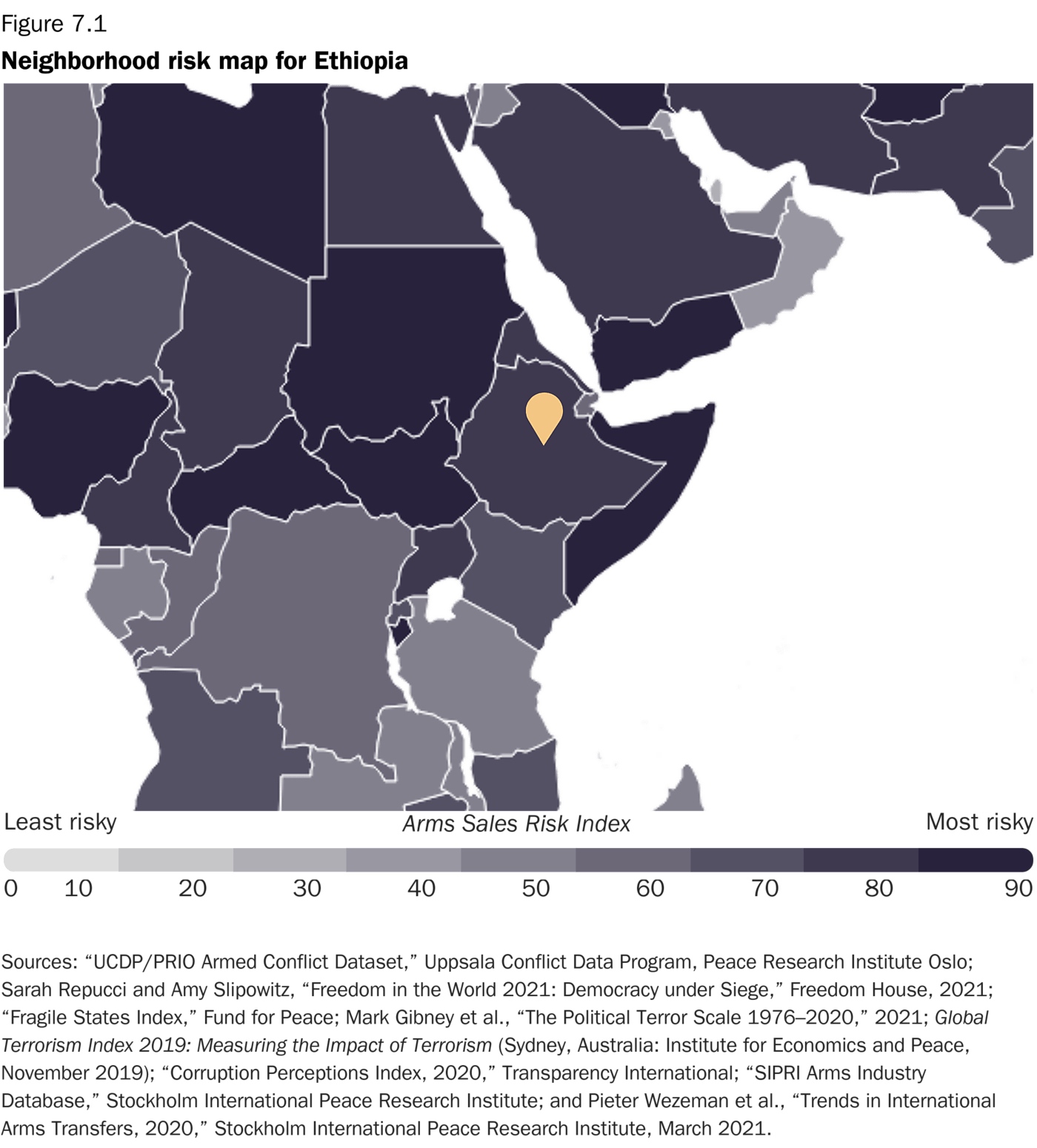

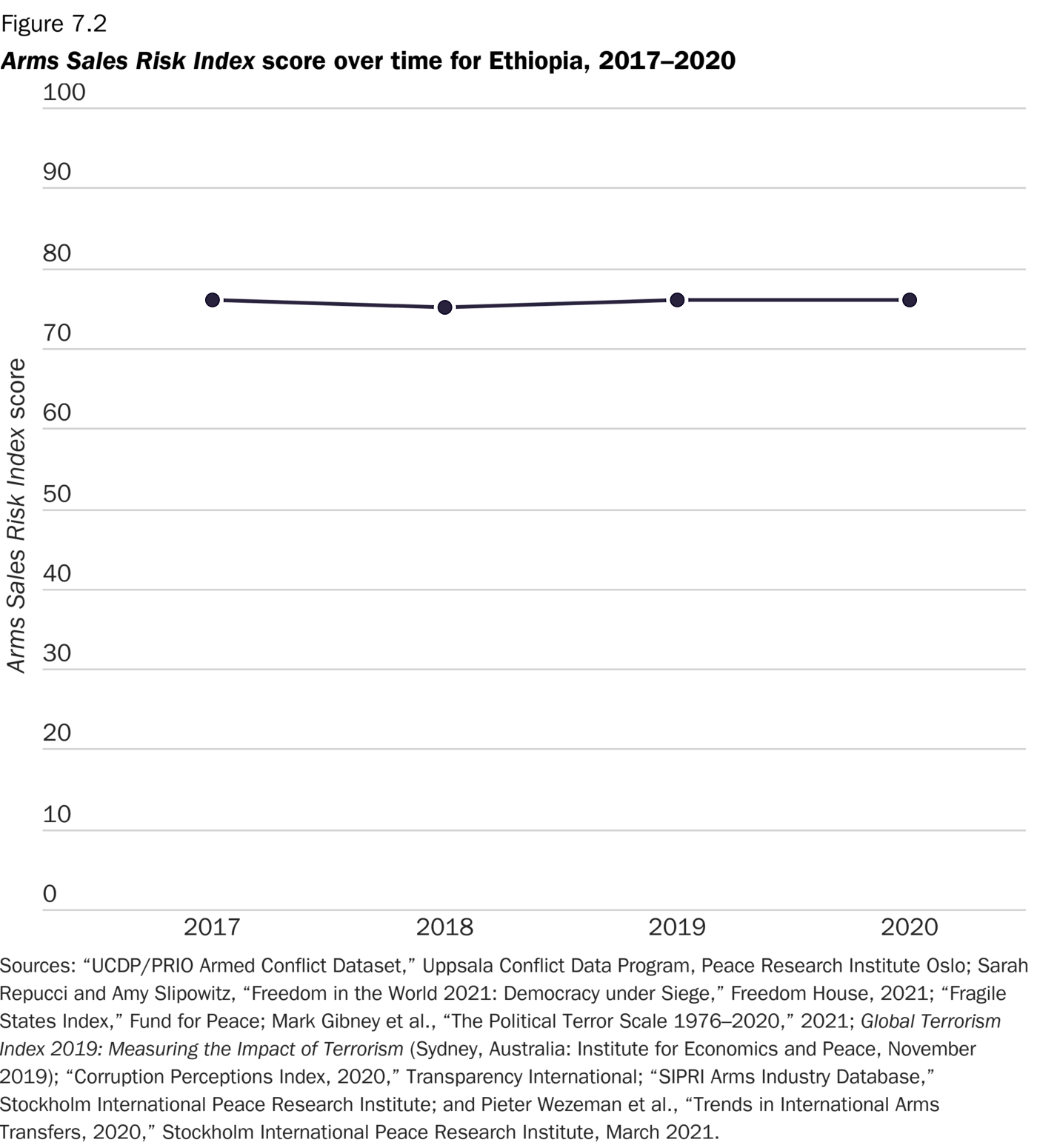

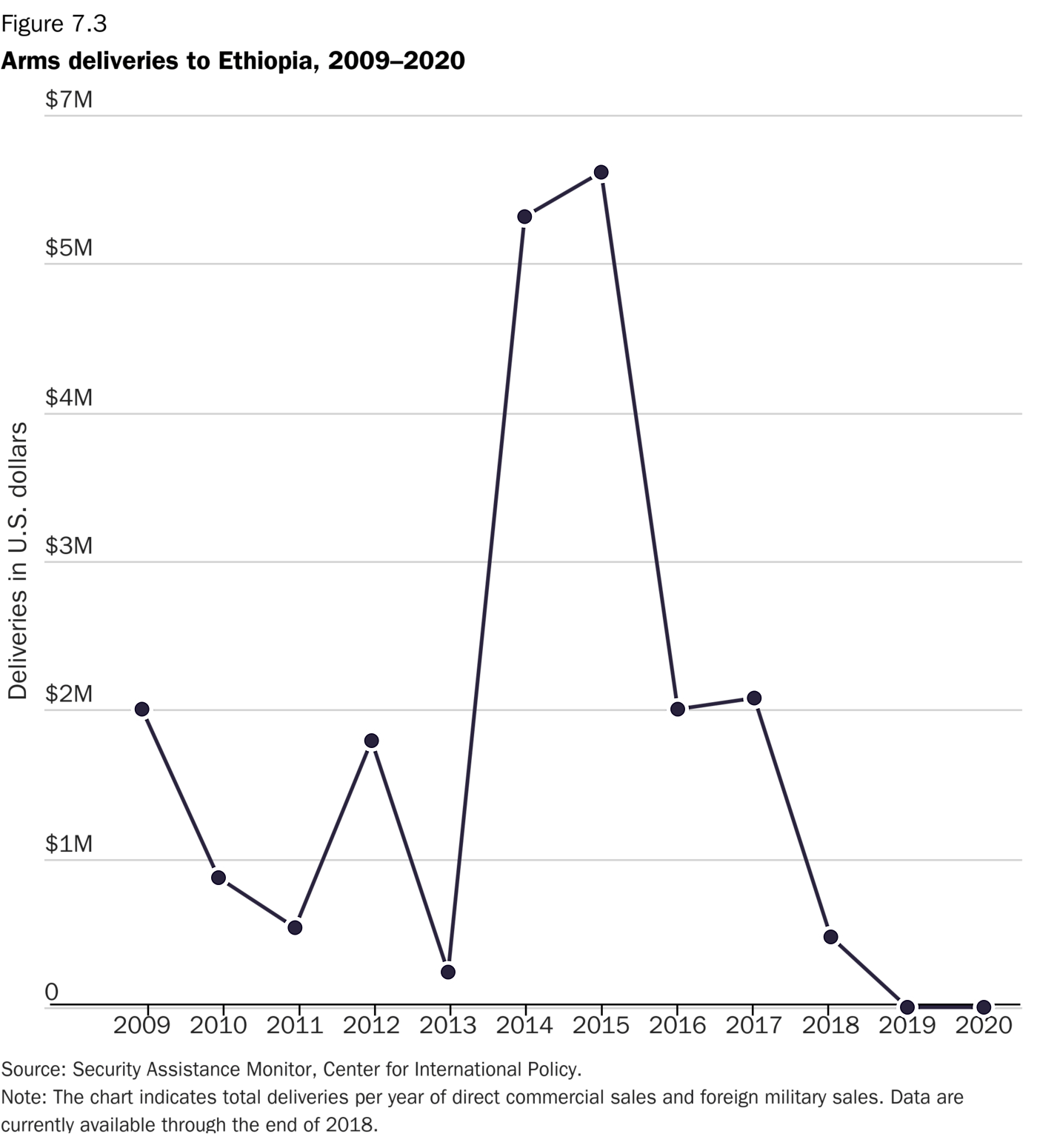

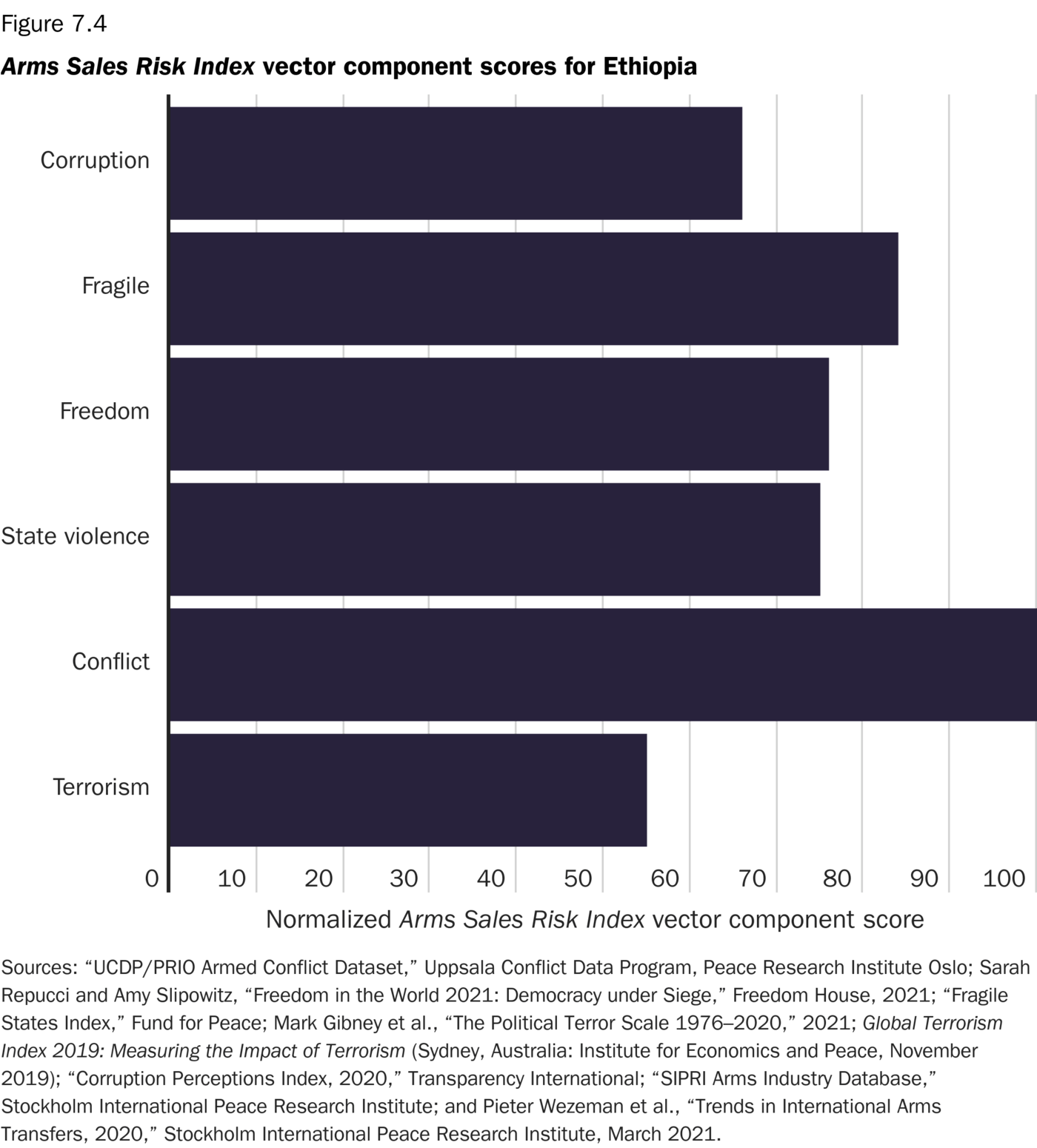

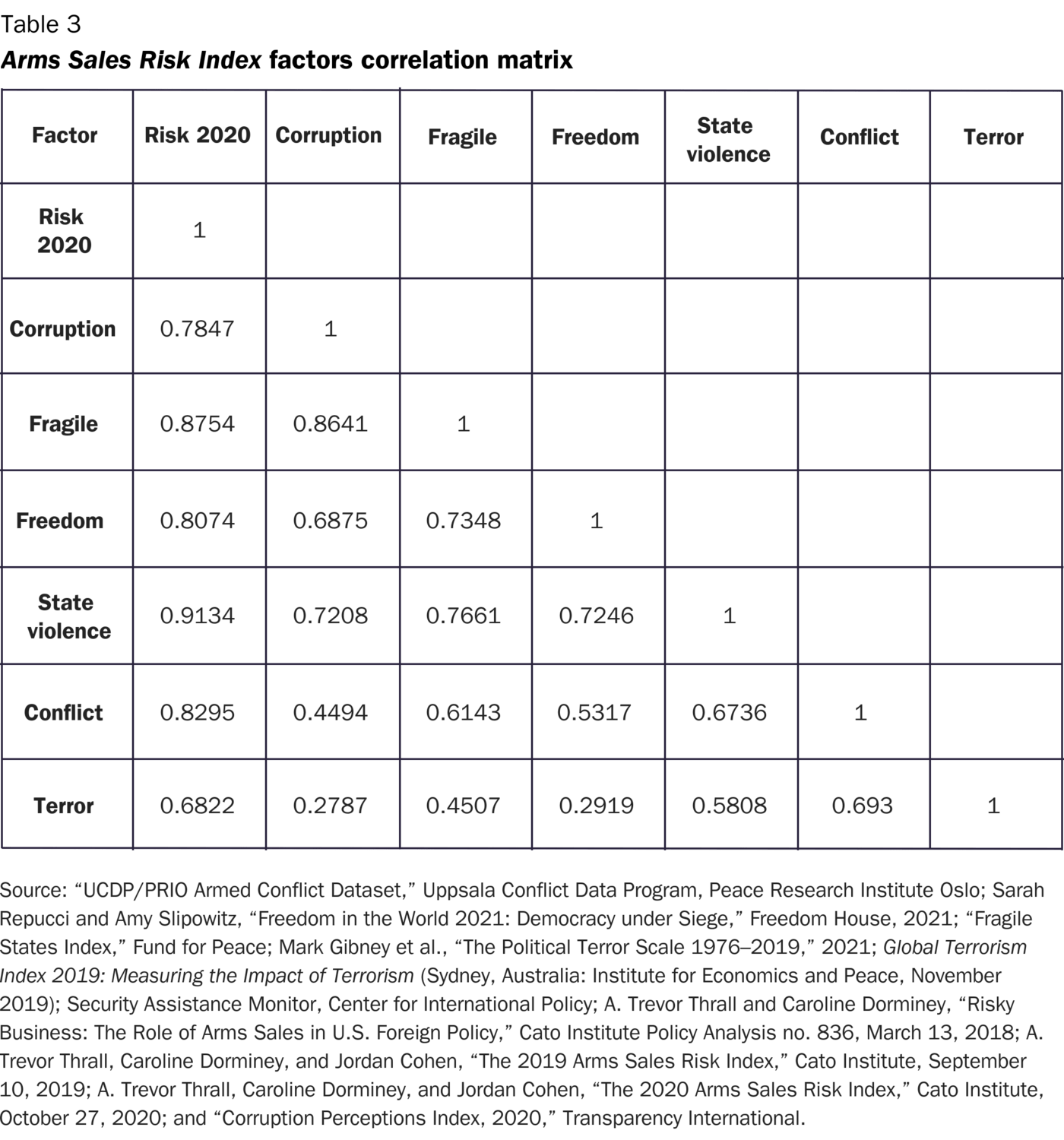

This year, our report includes a special section focused on the risks associated with the sale and transfer of small arms and light weapons (SALW). Though major conventional weapons like fighter jets, anti‐aircraft missile systems, and tanks comprise most U.S. arms sales from a financial perspective, SALW are far more likely to wind up in the wrong hands and to be used in ways that the United States does not intend. Despite this, more work remains to document the connection between the sales of SALW and diversion, diffusion, human rights violations, civilian casualties, and other negative consequences. To stimulate more discussion about the dangers of SALW and to encourage further research, we have assembled three case studies to demonstrate the links between risk factors, the sales of small arms, and the negative outcomes of these sales. We illustrate these negative outcomes from the studies of Mexico, Ethiopia, and the Philippines.

We invite scholars and policymakers to read this report and download the data for further analysis.