State Medicaid departments have a great deal of discretion over how they run and organize their Medicaid programs. This discretion ranges from the level of reimbursements for providers, to whether the program itself is centrally managed and run by the state or contracts care delivery to private managed care organizations (MCOs).

States can also choose to blend those latter two approaches. On one hand, a state’s size and concomitant bargaining power could allow it to obtain sizable discounts for services, drugs, and medical supplies. On the other, an MCO brings a wealth of experience from around the country and in the private insurance and Medicare sectors that could be leveraged into providing care at a lower cost. Blending the two approaches hopes to capture both benefits.

We suggest that market power alone, harnessed by centralized purchasing, is not sufficient to justify state governments managing their Medicaid contracts. To support this, we use data from Michigan and Illinois to show that, with cutting-edge drugs, Illinois’s decision to make extensive use of MCOs saved taxpayers tens of millions of dollars.

Hepatitis C’s Deadly and Growing Threat

Hepatitis C is a liver infection that is spread primarily through contact with blood from an infected person. Most people become infected with the hepatitis C virus by sharing needles or other equipment used to prepare and inject drugs. For some people, hepatitis C is a short-term illness lasting less than six months, but for about 80% of infected people it becomes a chronic infection. Chronic hepatitis C can result in life-threatening health problems like cirrhosis and liver cancer, and it is the primary indication for liver transplant. While there are vaccines available for hepatitis A and B, there is no vaccine for hepatitis C.

In the most recent data, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate there were 50,300 new cases of hepatitis C in 2018, up from an estimated 24,700 cases in 2012. There is a wide gap between the number of reported cases and the number of estimated cases, which researchers ascribe to the fact that many people with hepatitis C are asymptomatic and not everyone with symptoms seeks testing and treatment. Further, local and state jurisdictions with inadequate state or local public health offices can fail to count even those who have been diagnosed. Some 15,713 deaths were attributed to hepatitis C in the United States in 2018. That figure almost assuredly underestimates the true number.

Because of the nature of how hepatitis C spreads — mainly via sharing needles among drug addicts — its sufferers skew younger and tend to be from lower-income households. The CDC reports that two-thirds of acute hepatitis C cases reported in 2018 were 20–39 years of age. Nearly three-fourths of those with acute cases who were asked reported injection drug use.

A Treatment Breakthrough

The introduction of direct-acting antivirals in the early 2010s was a game-changing moment, providing a cure for hepatitis C. The treatment is not cheap, at least in relation to extant pharmacotherapies. The list retail price for a course of these drugs was nearly $100,000 when they were first introduced, although it fell significantly as more pharmaceutical companies entered the market with competing drugs, and insurance companies and governments received significant discounts on the price. Regardless, relative to the cost of liver transplant (the surgery costs roughly $575,000 and the subsequent lifetime of anti-rejection drugs costs $36,000 per year), the antivirals are remarkably cost-effective for patients with the most common type of hepatitis C and other early-stage liver disease.

Much of the focus on these drugs since their introduction has been on the potential effect on state Medicaid budgets. Because the Medicaid population is disproportionately affected by hepatitis C, the cost of these drugs can wreak havoc with states’ short-term budgets. For many policymakers, those fiscal exigencies have overshadowed the incredible benefit that these drugs cure a disease that kills roughly 400,000 people a year globally. Besides the health benefit, the short-term cost of the drugs indisputably reduces the long-term cost of caring for a chronically ill patient or a liver transplant and subsequent care.

One might cynically note that while liver transplants are expensive, livers are difficult to acquire and comparatively few liver transplants are performed. In 2017 only 8,082 liver transplants were performed in the United States. With 50,000 new hepatitis C cases per year, most of which will develop into chronic cases involving liver disease, there will never be enough livers available for transplantation. In other words, while one alternative for those with hepatitis C may be an expensive transplant, most people will be unable to procure an organ.

Medicaid Managed Care in Illinois and Michigan

Generally speaking, there are two ways for states to approach the procurement of drugs for their Medicaid populations: via pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and via centrally coordinated — that is, government — purchasing. These two approaches are exemplified by the two Midwestern states we examined. In Illinois, the government pushed heavily into Medicaid managed care, including the use of PBMs, to coordinate the procurement of pharmaceuticals for Medicaid enrollees. In Michigan, the government also moved into Medicaid managed care but pulled back some service lines to centrally coordinate purchasing — namely specialty pharmacy products, including hepatitis C drugs.

Managed care involves the use of close coordination of care for enrollees to ensure that they obtain access to necessary care in a timely and efficient manner. MCOs typically contract with hospitals and physicians to obtain preferential pricing for services along with assurances of access to care. Additionally, MCOs work with PBMs to ensure ease of access to drugs for enrollees. Contracts between states and MCOs are generally structured such that efficient care delivery rewards both the state and the MCO. The use of managed care in Medicaid is not new and its effects on health care use have been studied for decades.

Despite tight federal guardrails, the states have significant discretion in how their Medicaid programs operate. For example, states can structure contracts with a variety of features, including risk adjustment mechanisms and performance guarantees. Another commonly employed mechanism is a “carve-out,” whereby the state retains administrative purchasing control over some components of the covered benefits, such as pharmacy benefits or in some cases behavioral health care. One recent survey revealed that while only four states fully carved out their pharmacy benefit, many more states were considering it. Moreover, some states will selectively carve out subsets of drugs, such as high-cost product classes. Five states (including Michigan) have also carved out hepatitis C treatments.

A common argument used to justify carving out pharmacy benefits is that centralizing all Medicaid purchasing to a single state entity will reduce administrative costs and “streamline” care, in addition to — theoretically, at least — allowing for states to exercise greater leverage over pricing. However, it remains an empirical question whether the states have the wherewithal to take advantage of the purported greater leverage they gain from centralization. That is the central question of our research.

DATA

We use the State Drug Utilization Data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in our analysis. The CMS requires states to report drug utilization data for covered outpatient drugs (including specialty pharmacies) that are paid for by state Medicaid agencies since the start of the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. These data include state, drug name, National Drug Code, number of prescriptions, and dollars reimbursed.

Importantly, the data separate managed care drug purchases via MCOs from fee-for-service purchases via the state. We identify all hepatitis C virus utilization quarterly from the third quarter of 2015 until the end of 2019. Data for both states were not consistently and reliably available in 2020 nor prior to the third quarter of 2015. We use these data to compute the weighted average of the amount paid per course of treatment by quarter for MCOs and fee-for-service operations (FFS) in both Illinois and Michigan from the third quarter of 2015 to the fourth quarter of 2019.

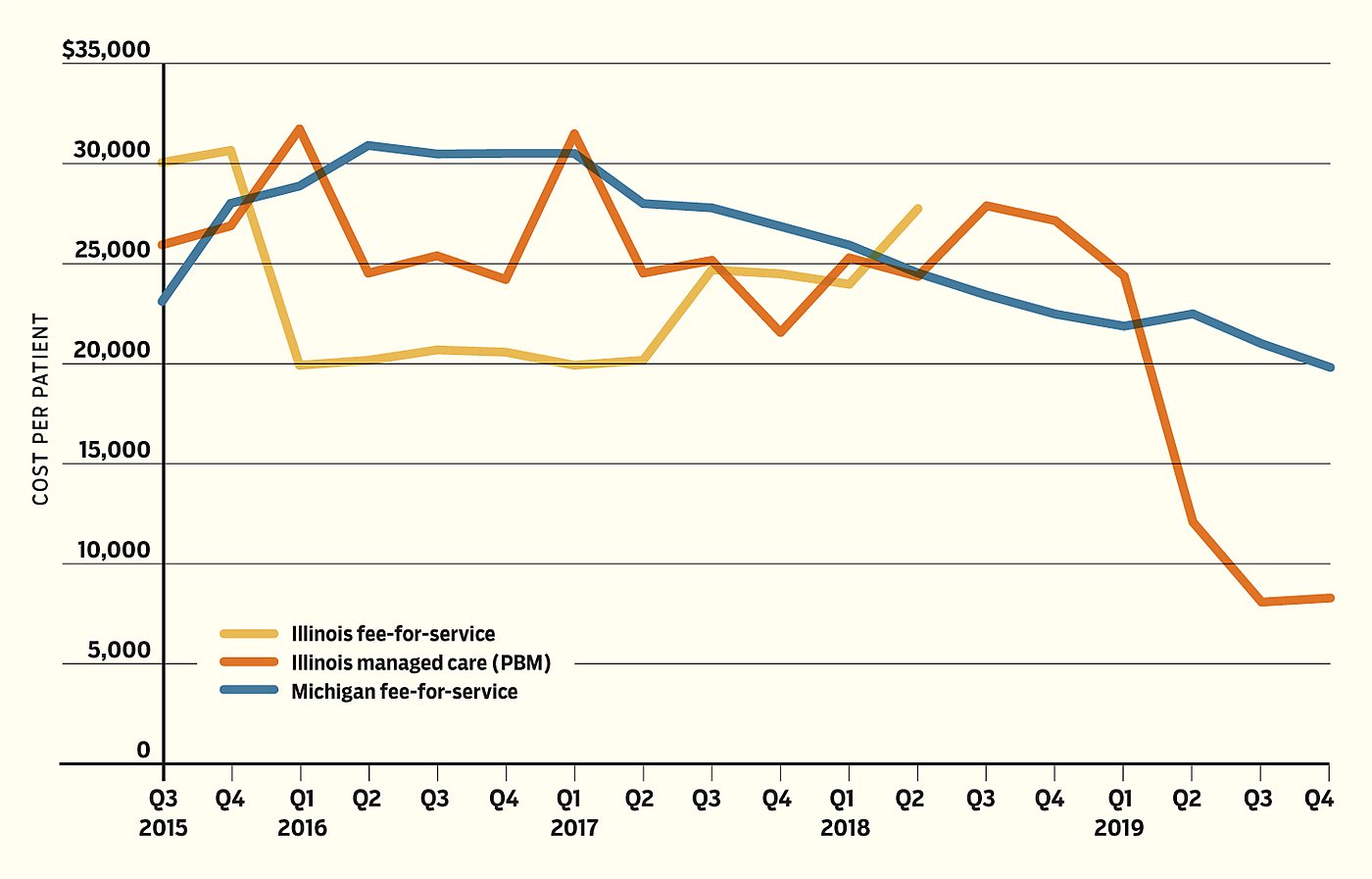

Figure 1

Per-Patient Cost of Antiviral Drug Treatment for Hepatitis C

Results

Figure 1 displays the prices paid for these drugs by Illinois’s FFS and MCOs as well as Michigan’s FFS. Unit prices for all three categories began close to one another, but shortly after Michigan centralized purchasing of the hepatitis C treatments by the middle of 2015, its per-unit prices increased and remained above those in Illinois for the next three years. The Illinois FFS ceased provision of substantial quantities of hepatitis C antivirals in the spring of 2018 and its MCOs were doing nearly all the prescribing. The next year, Michigan’s prices fell below Illinois’s.

The critical period begins one year later, in the spring of 2019, when substantially cheaper generic forms of the branded drugs Epclusa and Harvoni became available. Illinois’s MCOs rapidly switched to the generics, while in Michigan the central Medicaid agency continued purchasing the branded drug Mavyret. While the products have different active ingredients, they are all highly efficacious in treating hepatitis C. Indeed, the plethora of competing products available highlights the ability of PBMs to negotiate effectively with manufacturers.

Over the next nine months, average unit price per prescription in Illinois fell by well over 50%, to just over $8,000 by the second half of 2019, while it remained over $20,000 per prescription in Michigan. The cost of the price stasis was significant. Had Michigan paid the same prices as Illinois in the latter part of 2019 alone, the state would have saved nearly $36 million. This costly inability to respond to the evolving availability of cheaper drugs, perhaps because of inflexibly written contracts or simple inattention, represents the fundamental flaw in criticisms of the private market.

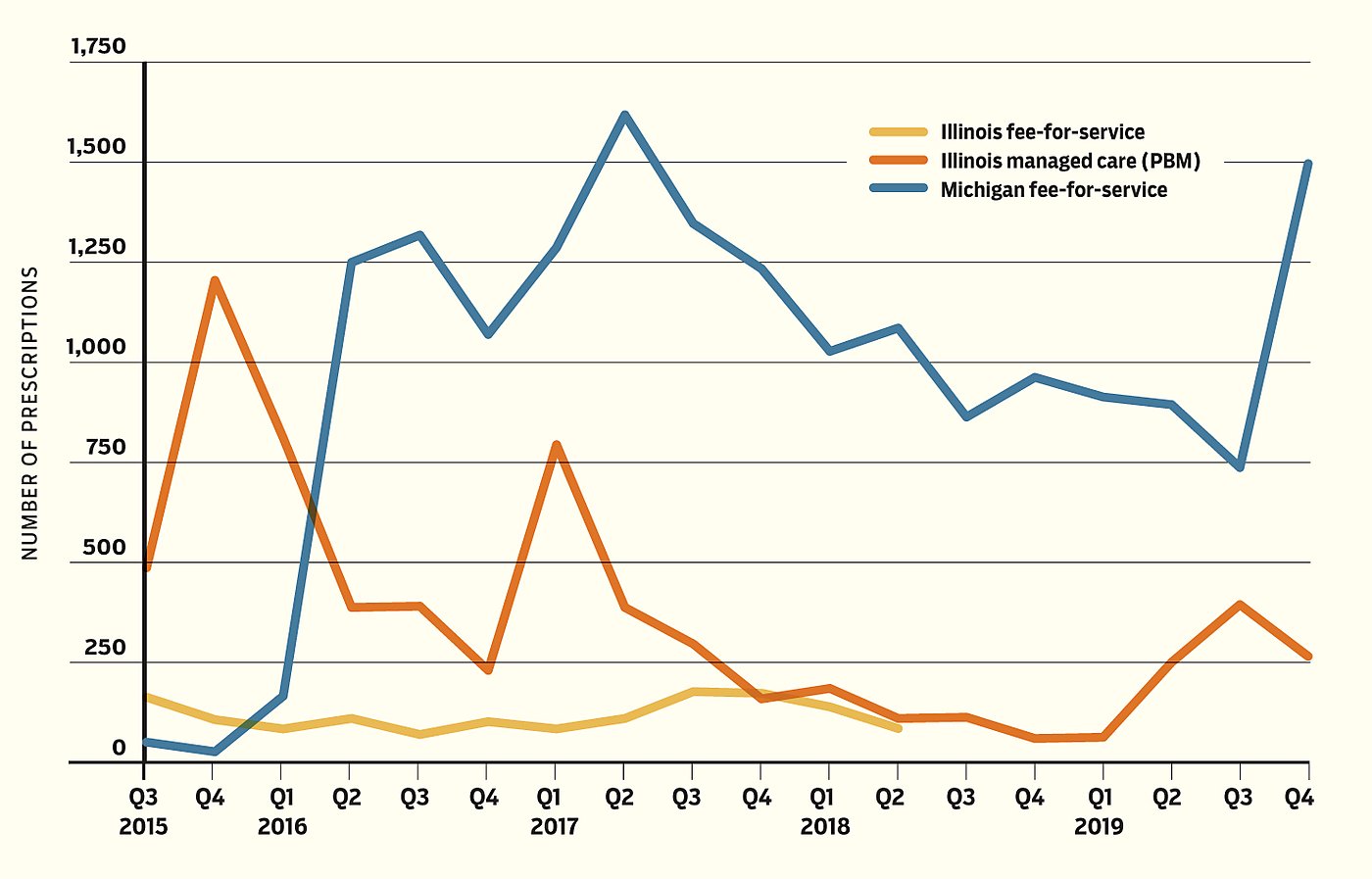

It is worth noting that Michigan filled more hepatitis C prescriptions than did Illinois (Figure 2), although the total number of hepatitis C cases is similar between the two states. The difference may be partly attributable to Illinois’s relatively restrictive eligibility policy for hepatitis C treatment at the time. It could also be partly attributable to more efficient utilization management brought about by the PBMs. Illinois could direct the MCOs to manage utilization more efficiently as a protection from unnecessary utilization by enrollees who could tolerate waiting with minimal effect on quality of life. More detailed data could potentially elucidate this subtle aspect of managed care.

Nevertheless, the fact that Illinois pays a far lower unit price for treatment means that it could substantially increase access to this curative therapy if it desired. Conversely, there is no reason that Michigan should not be able to use its volume purchasing to further reduce its payments, but it still appears to pay more than Illinois.

Figure 2

Antiviral Hepatitis‑C Prescriptions

One potential limitation to our analysis is that the CMS data do not include the amount of any supplemental rebate that might be obtained by either the state or the PBM. These days, a few states have turned to non-traditional models like the subscription models adopted in Louisiana and Washington, which allow for unlimited access to a specific hepatitis C drug for a fixed global price. While it is certainly plausible that Michigan receives a supplemental rebate, it is implausible that it comes close to closing the 55% gap between unit prices in Illinois and Michigan. Moreover, supplemental rebates obtained by MCOs in Illinois are no less likely to be substantial, particularly given the experience MCOs have through their PBMs throughout the private insurance and Medicare Part D markets.

A Tale of Two States and Two Systems

In our analysis of two states and one therapeutic class of life-saving medication, we present a cautionary tale of the pitfalls of believing that centralized purchasing can achieve better savings than the private sector. Our work highlights an often-overlooked aspect of the role of the private market in health care delivery: MCOs in general — and PBMs in particular — have incentive to move more nimbly in response to changing market conditions. In the case of hepatitis C therapies, the predicate has been the rapidly evolving availability of generics. Had Michigan been able to react with the alacrity of the PBMs in Illinois, we estimate it could have saved taxpayers as much as $50 million per year.

No one is arguing that any state should abandon its role of providing for the health care of citizens who lack the means to pay for it. However, government need not directly provide that care. Michigan’s insistence that the government arrange for the purchasing of its drugs and not a private-sector middleman has cost its taxpayers dearly. While centralizing its purchasing gives it a greater heft in the market that it can leverage to obtain quantity discounts, the state’s inability to move adeptly in the marketplace prevented it from taking advantage of rapid changes in the marketplace.

Illinois, which relied on PBMs to manage its drug purchases, exploited the introduction of generic drugs to treat hepatitis C to extract considerable savings. Our observation illustrates that a savvy state can use the market to provide more cost-effective health care treatment to its citizenry.

In the case of hepatitis C treatments, the ultimate savings to the state undoubtedly exceeded the savings from its lower per-unit drug costs. By fully benefiting from the reduced costs in the market, the debt-constrained state is in a better position to expand the use of hepatitis C drugs, which should greatly reduce the long-term costs of treating this chronic illness, primarily by reducing the need for liver transplants.

It might be tempting to argue that, given the circumstances surrounding hepatitis C medications, this example is not generalizable to other medications. However, it is our belief that the hepatitis C treatment experience is relevant because it puts in stark relief the largely unseen advantages of PBMs over state-directed purchasing decisions. Critically, this same process unfolds to a smaller degree every day with thousands of other drugs.

Moreover, we believe the experience is relevant because this is not the last of expensive curative therapies. Indeed, it is likely only the beginning. The important take-away is that the value of expertise in the drug market space will only grow in the future.

There is too much at stake to task overworked and under-resourced state Medicaid departments with the job of being experts on the ever-changing competitive landscape of the pharmaceutical market. A better strategy is to write contracts with private companies in which everybody wins: patients gain access to life-improving therapies at the same time that taxpayers share in the gain from leveraging competitive forces to obtain better prices for drugs.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.