Introduction

What role should arms sales play in American foreign policy? Though major deals — like Trump’s $110 billion agreement with Saudi Arabia announced in 2017 or the decision to sell arms to Ukraine — provoke brief periods of discussion, there is no real debate in Washington about the wisdom of exporting vast quantities of weapons around the globe to allies and nonallies alike. Congress, which has the authority to cancel arms deals, has not impeded a deal since the passage of the 1976 Arms Export Control Act created the framework for doing so. Since 9/11 the pace of sales has increased. From 2002 to 2016, the United States sold roughly $197 billion worth of weapons and related military support to 167 countries.1 In just his first year Donald Trump cut a deal worth as much as $110 billion to Saudi Arabia alone and notified Congress of 157 sales worth more than $84 billion to 42 other nations.2 Despite losing market share over the past two decades because of increasing competition, the United States still enjoyed the largest share of the global arms trade between 2012 and 2016 at 33 percent.3

The current consensus in favor of arms sales rests on three planks. First, advocates argue that arms sales enhance American security by bolstering the military capabilities of allies, enabling them to deter and contain their adversaries, and helping promote stability in critical areas like the Middle East and Southeast Asia. Second, they argue that arms sales help the United States exert influence over the behavior and foreign policies of client nations. Finally, advocates argue that arms sales provide a boon to the U.S. economy and fiscal benefits in the form of lower unit costs to the Pentagon, while helping ensure the health of the American defense industrial base.4

We argue, however, that Washington’s faith in the wisdom of foreign arms sales is seriously misplaced. The benefits tend to be oversold, and the downsides are often simply ignored. The defense industry and its champions, in particular, have long exaggerated the economic boon of arms sales.5 And even if they were greater, economic benefits alone are not worth subverting strategic considerations. More importantly, the strategic deficits of arms sales are severe enough to overwhelm even the most optimistic economic argument. It is the strategic case for and against arms sales that we consider in this analysis.

Arms sales create a host of negative, unintended consequences that warrant a much more cautious and limited approach, even in support of an expansive grand strategy like primacy or liberal hegemony. From the perspective of those who would prefer a more restrained American foreign policy, the prospective benefits of engaging in the arms trade are even smaller. Even in cases where the United States wants a nation to arm itself, there is rarely a need for the weapons to come from the United States. Moreover, the United States would generate significant diplomatic flexibility and moral authority by refraining from selling arms. Given these outsized risks and nebulous rewards, the United States should greatly reduce international arms sales.

To develop our argument we begin in section one with a quantitative analysis of U.S. arms sales since 9/11 in order to illustrate the dangerous track record of recent sales. We then provide a brief history of U.S. arms sales policy to provide a context for the current process in section two. Section three outlines the advocates’ case for arms sales and section four outlines the case against. We conclude with a brief discussion of the current politics of the arms trade and a series of policy recommendations.

U.S. Arms Sales since 9/11: Assessing the Risk from Arms Sales

In order to comply with the Arms Export Control Act (AECA), the U.S. government must generate a risk assessment in order to confirm that sales are unlikely to produce unwanted outcomes. This requirement makes sense, because history shows that arms sales can lead to a host of negative, unintended consequences. These consequences come in many forms, from those that affect the United States, such as blowback and entanglement in foreign conflicts, to those that affect entire regions, such as instability and dispersion, to those that affect the recipient regime itself, such as enabling oppression and increasing the likelihood of military coups. Forecasting how weapons will be used, especially over the course of decades, is difficult, but history provides evidence of the factors that make negative outcomes more likely. Sadly, however, even a cursory review of American arms sales over time makes it clear that neither the White House, nor the Pentagon, nor the State Department — all of which are involved in approving potential sales — takes the risk assessment process seriously.

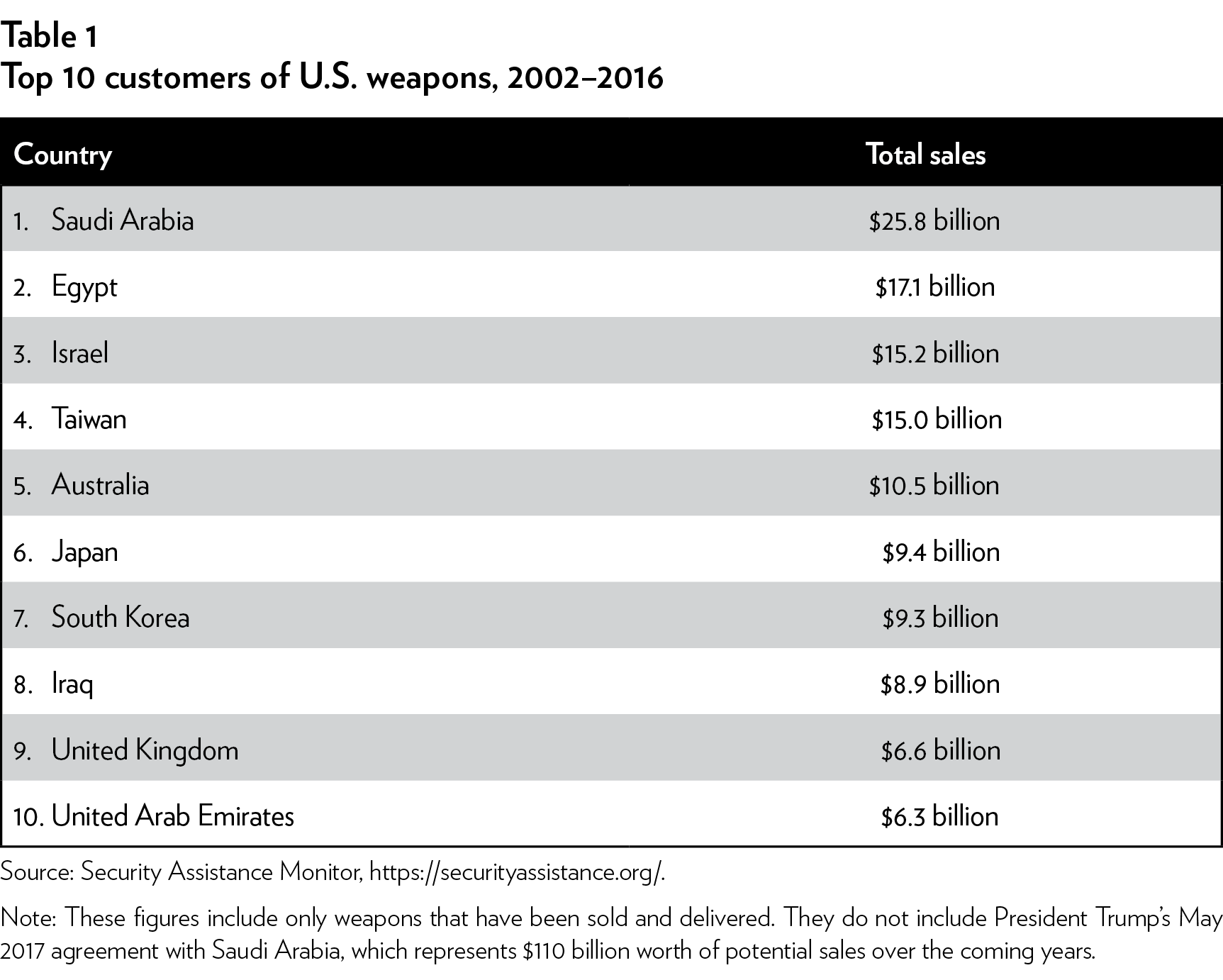

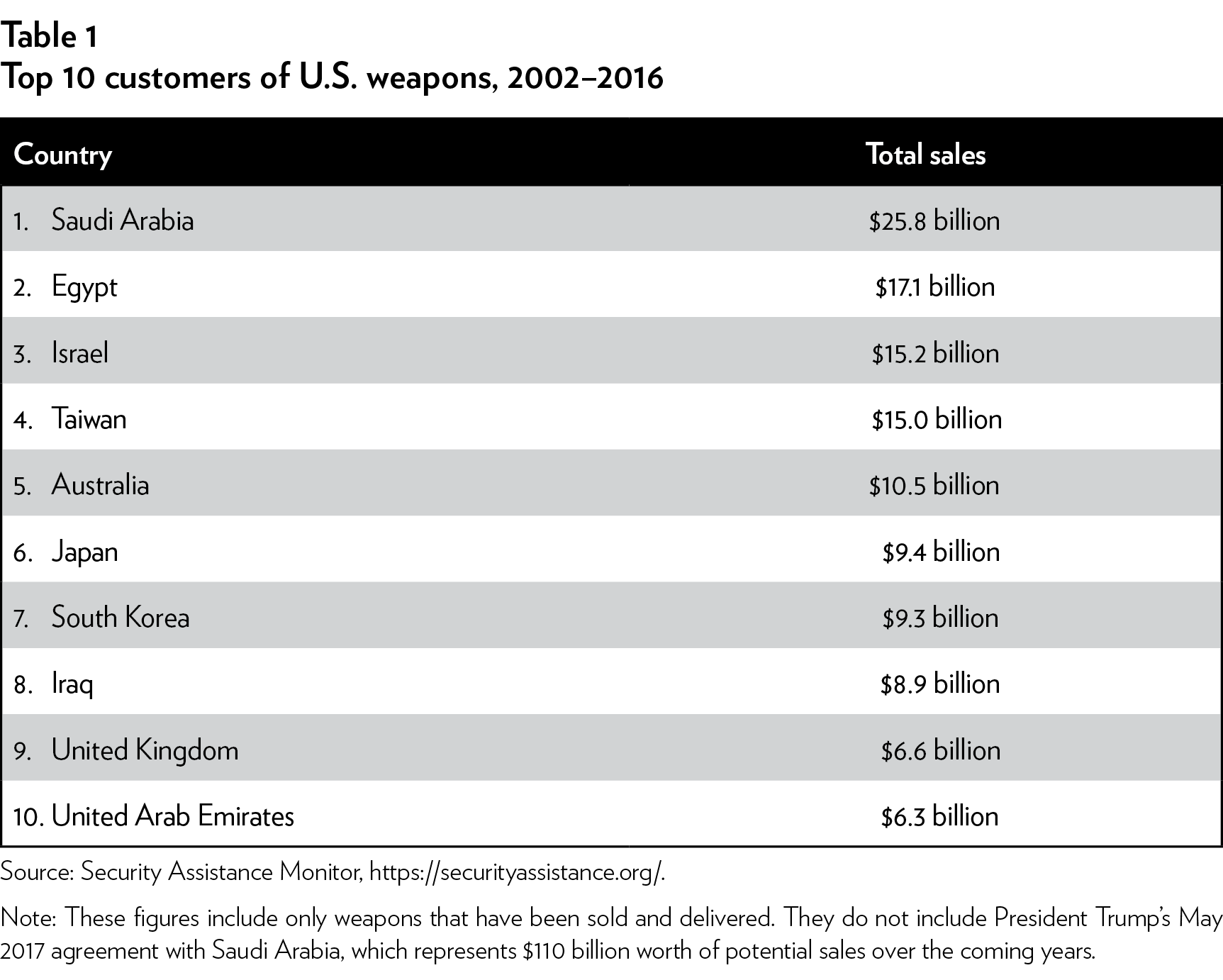

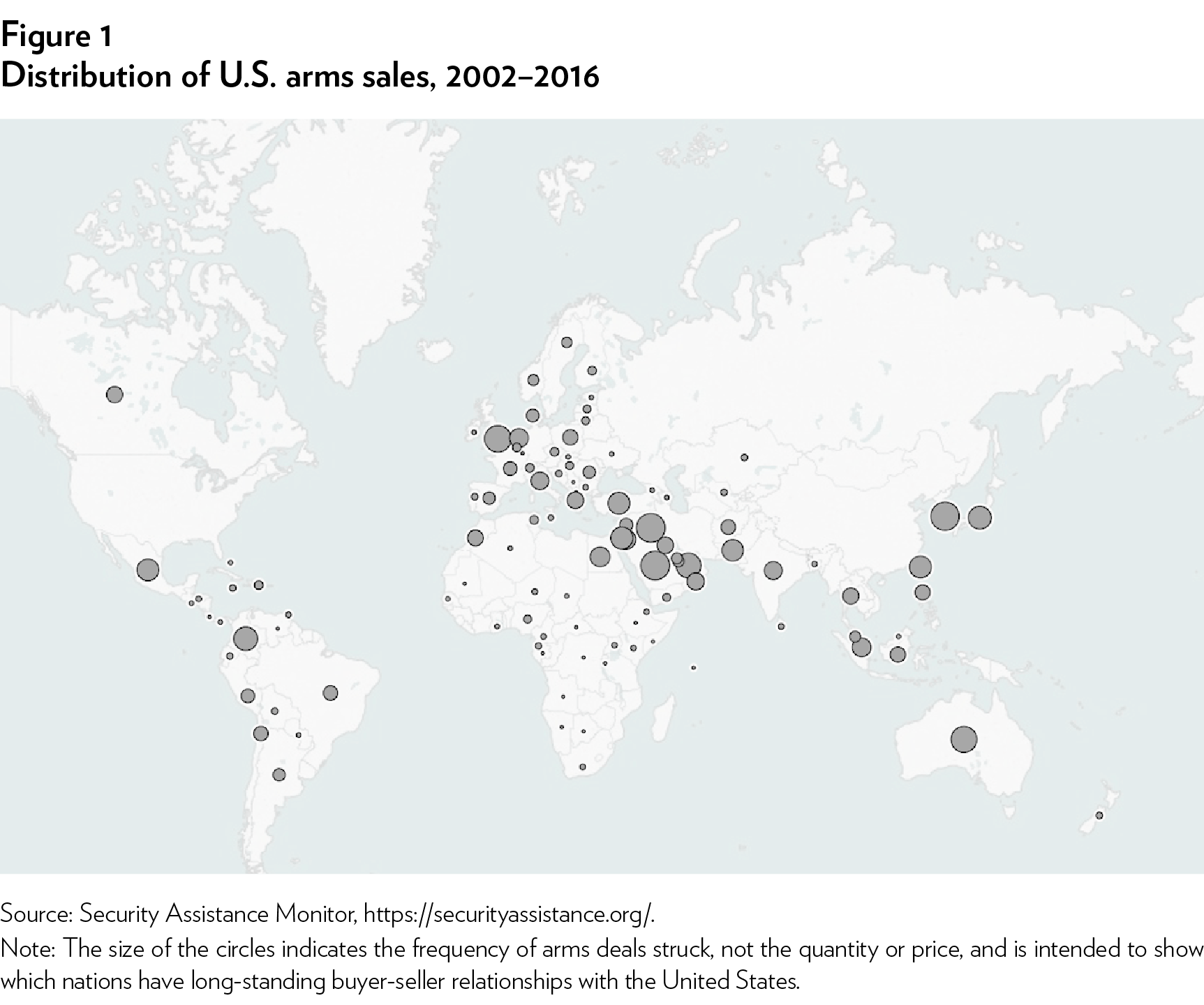

Historically, the United States has sold weapons to almost any nation that wanted to buy them — suggesting that the risk assessment process is rigged to not find risk. From 2002 to 2016, America delivered $197 billion in weapons to 167 states worldwide.6 Thirty-two of these countries purchased at least $1 billion in arms. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was America’s biggest client, purchasing $25.8 billion worth of weapons — including F-15s and a litany of helicopters, naval assets, and associated munitions. As shown in Table 1, the top 10 clients collectively bought $124 billion in arms — accounting for roughly two-thirds of the value of America’s total global exports since 2002. Given the amount of chaos, instability, and conflict in the world, it is difficult to imagine what sort of process would assess as many as 167 of the world’s roughly 200 countries as safe bets to receive American weapons.

Moreover, the United States has a long history of selling weapons to nations where the immediate risks were obvious. From 1981 to 2010, the United States sold small arms and light weapons to 59 percent and major conventional weapons to 35 percent of countries actively engaged in a high-level conflict. The United States sold small arms to 66 percent and major conventional weapons to 40 percent of countries actively engaged in a low-level conflict.7 As one author noted, in 1994 there were 50 ongoing ethnic and territorial conflicts in the world and the United States had armed at least one side in 45 of them. Since 9/11, the United States has sold weapons to at least two dyads in conflict: Saudi Arabia and Yemen, and Turkey and the Kurds.8

To produce a risk assessment of American arms recipients since 2002, we consulted previous research to identify the risk factors most commonly associated with both short- and long-term negative outcomes. Unfortunately, there are no hard data on the precise relationship between many of these risk factors and the probability of negative outcomes. We also lack data entirely for certain risk factors that we would otherwise have included. A nation’s previous use (and misuse) of American weapons, for example, is clearly among the most important factors to assess. Neither the government nor academic research, however, exists to inform such an assessment. As a result, we take a conservative approach, creating an index of overall riskiness based on straightforward assumptions about the correlations between risk factors and negative outcomes on data that are available, rather than attempting to make precise predictions about the impact of each specific risk factor, or speculating about the impact of factors we cannot measure.

The first risk factor we consider is the stability of the recipient nation. We assume that fragile states with tenuous legitimacy and little ability to deliver services and police their own territory, or those that cannot manage conflict within their borders, pose a greater risk for the dispersion and misuse of weapons. Research also indicates that military aid can increase the likelihood of a military coup, an outcome even more likely in the case of a fragile state.9 To measure this factor, we take the most recent score for each nation on the Fragile States Index, which determines a state’s vulnerability by looking at a range of economic, political, and social factors.10

The second risk factor we look at is the behavior of the state toward its own citizens. We assume that states that rank poorly on human rights performance or that regularly use violence against their own people pose a greater risk of misusing weapons in the short or long term. To measure this we rely on two sources: Freedom House’s Freedom in the World rankings, which assess “the condition of political rights and civil liberties around the world,”11 and the State Department’s Political Terror Scale, which provides a more specific measurement of a state’s use of torture and violence against its citizens.12

Finally, we consider the level of conflict, both internal and external, each state is engaged in. We assume that countries dealing with widespread terrorism and insurgency, or actively engaged in an interstate conflict, also represent higher risks of negative outcomes such as dispersion, blowback, entanglement, conflict, and human rights abuses. Though the United States may have reasons to provide arms to nations engaged in such conflicts or dealing with terrorism, the risk of negative consequences remains. To assess these factors, we rely on the Global Terrorism Index, which measures the scope of terrorism in a country, and the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset, published by the Uppsala Conflict Data Program and the Peace Research Institute Oslo, which tracks each country’s involvement in wars as well as in smaller conflicts.13

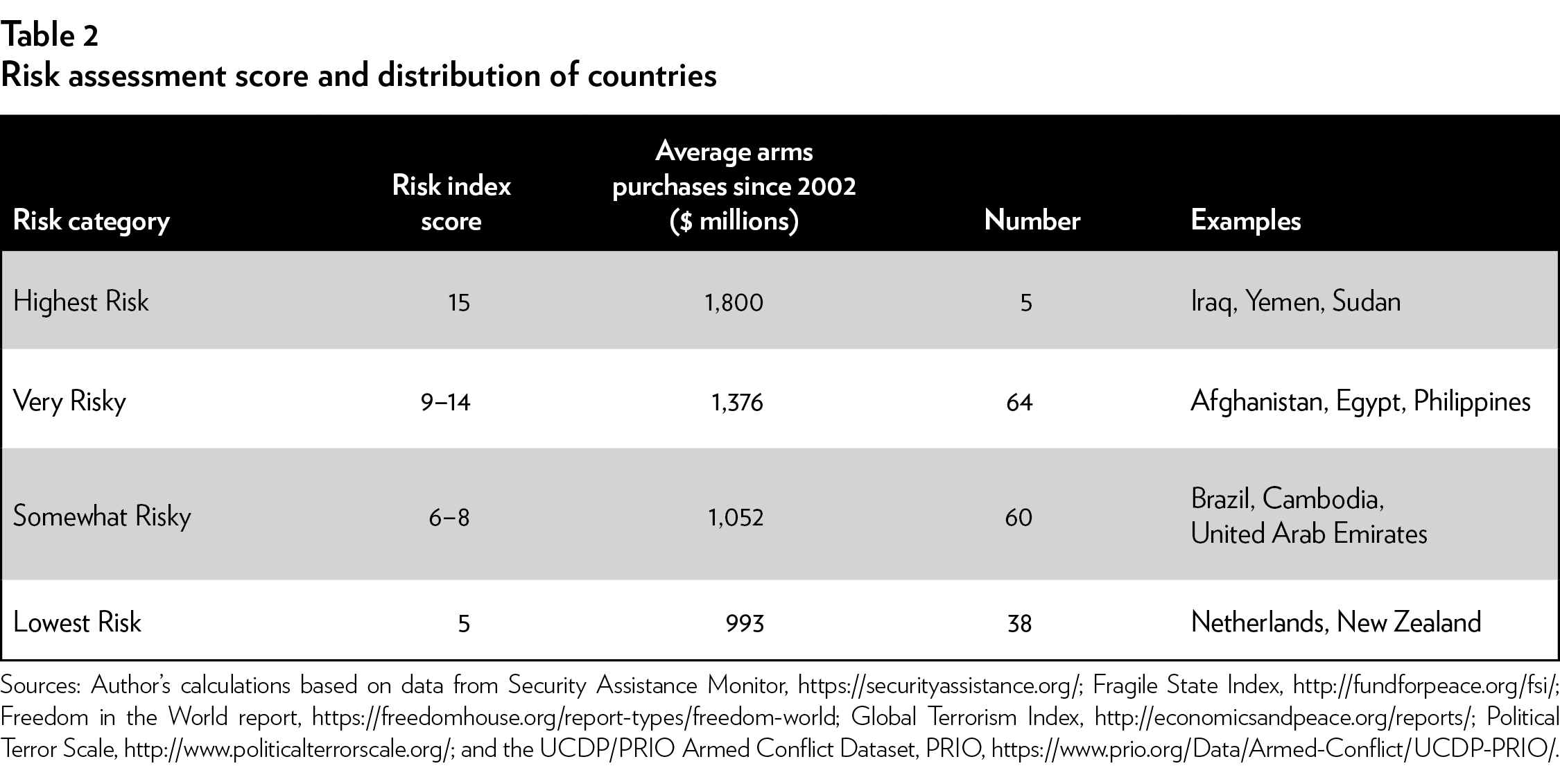

To gauge the riskiness of selling weapons to a given country, we combined its scores on these five metrics into a single risk index score. Since the measures all used different scales, we first recoded each of them into three categories: low, medium, and high risk. For example, we coded “not free” countries as high risk (3 points); “partly free” countries as medium risk (2 points); and “free” countries as low risk (1 point). The result was a risk index that runs from 5 (countries scoring “low risk” on all measures) to 15 (countries scoring “high risk” on all measures).

To facilitate our reporting we then grouped the results into four risk categories. We gave the Highest Risk designation to the 5 countries that scored as “high risk” on every measure. At the other end of the spectrum, the Lowest Risk category contains the 38 countries that rated as “low risk” on all five measures. The categories between these two are Very Risky (64 countries) and Somewhat Risky (60 countries). Table 2 reveals the distribution of countries across risk categories as well as the average total arms sales by category since 2002.

Three important observations immediately emerge from the analysis. First, there are a large number of risky customers in the world, and the United States sells weapons to most of them. Thirty-five nations (21 percent) scored in the highest-risk category on at least two metrics, and 72 (43 percent) were in the highest-risk category on at least one of the five measures. There simply are not that many safe bets when it comes to the arms trade.

Second, the data provide compelling evidence that the United States does not discriminate between high- and low-risk customers. The average sales to the riskiest nations are higher than those to the least risky nations. Considering discrete components of the index, for example, the 22 countries coded as “highest risk” on the Global Terrorism Index bought an average of $1.91 billion worth of American weapons. The 28 countries in active, high-level conflicts bought an average of $2.94 billion worth of arms.

Applying our risk assessment framework to the list of 16 nations currently banned from buying American weapons helps illustrate the validity of our approach. The average score of banned nations is 11.6, with 12 nations scoring 10 or higher. The highest-scoring nations were Syria, Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with Iran, Eritrea, and the Central African Republic not far behind. Clearly these are nations to which the United States should not be selling weapons. What is especially troubling is that the United States sold weapons to several of these countries in the years right before sales were banned, when most of the risks were readily apparent. Moreover, America’s customer list includes 32 countries with a risk score above the average of those on the banned list. This reinforces our concern that the U.S. government does not block sales to countries that clearly pose a risk of negative consequences.

The third major observation is that this lack of discrimination is dangerous. As simple as it is, our risk assessment is a useful guide to forecasting negative consequences. The five countries that scored as high risk on all five measures provide a clear illustration of the risks of arms sales. This group, which purchased an average of $1.8 billion in U.S. weapons since 9/11, includes Libya, Iraq, Yemen, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Sudan. These five countries, recall, are classified by the various metrics as: “terror everywhere,” “not free,” “most fragile,” “large impact from terrorism,” and as being involved in high-level conflicts. These governments have used their American weapons to promote oppression, commit human rights abuses, and perpetuate bloody civil wars.

Within the Very Risky category, each country rated as “highest risk” on at least one measure, and 30 scored as “highest risk” on at least two measures. This group also represents the full range of unintended consequences from arms sales. Afghanistan, Egypt, Somalia, and Ukraine fall into this category. This group collectively spent an average of $1.38 billion over the time period. Since 9/11, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (which scored a 12) invaded Yemen, intervened in Tunisia and Syria, and provoked a crisis with Qatar, while cementing a track record of human rights abuses and government oppression. Other states in this category, such as Afghanistan (score of 14), have entangled the United States in counterproductive conflicts since 9/11 and continue to do so today.

Even arms sales to the less risky nations do not come without risk. For example, the Somewhat Risky category includes the United Arab Emirates, which is involved in an active conflict in Yemen, as well as Georgia, which has dangerous neighbors. Finally, the Lowest Risk category includes most of the NATO nations, Taiwan, South Korea, and a range of other, mostly smaller nations with stable governments, such as Barbados and Grenada, located in friendly neighborhoods. These countries pose little risk for problems like dispersion, destabilization, or misuse of weapons for oppression. In some cases, however, arms sales could alter regional balances of power in ways that increase tensions and the chance of conflict. U.S. arms sales to NATO allies, as part of the European Reassurance Initiative, for example, have upset Russian leaders.14 Similarly, arms sales to Taiwan, itself not a risky customer, have nonetheless raised tensions between China and the United States.15

In short, even a relatively simple risk assessment makes it clear that the policy of the United States is to sell weapons to just about any nation that can afford them without much concern for the consequences. Though the United States does limit its most advanced weapons to allies16 and maintains a ban on the sale of materials related to weapons of mass destruction,17 the United States has sold just about everything else, in many cases to countries embroiled in interstate and civil conflicts, to countries with horrendous human rights records, and to countries that represent a risk for entangling the United States in unwanted conflicts.

How Did We Get Here? The Evolution of U.S. Arms Sales Policy

Four major inflection points define the evolution of U.S. arms sales policy. The first was the end of World War II and the dawn of the Cold War. Though the U.S. government dabbled in international arms sales after World War I, it was not until after World War II that the United States conducted arms transfers on a large scale. As the Cold War heated up, federal investment in the research and development of new systems rose dramatically, as did international demand for American weapons. Competition between the United States and Soviet Union fostered a global boom in arms sales. Throughout the Cold War, the United States used arms sales as a key element of its defense of Western Europe and the broader American strategy of containing the Soviet Union and the spread of communism.18

The second inflection point in U.S. arms sales history was the passage of the American Export Controls Act (AECA) and the establishment of the modern arms sales process. Wary of getting involved in future Vietnams but determined to retain America’s global leadership role, President Richard Nixon turned to arms transfers as a way to “wield force and exert influence” without sending American troops abroad.19 In the absence of legislation regulating the president’s use of arms sales, Nixon was able to ramp up arms sales quickly and quietly, in most cases without notifying Congress or the public. Nixon’s embrace of this strategy led to a tenfold expansion in arms sales in the early 1970s as the administration shipped weapons to Iran, Cambodia, and Laos.20

Though Nixon’s general anti-communist strategy had bipartisan support, Nixon’s policies themselves led to negative consequences in several cases. Sen. Gaylord Nelson, champion of the AECA, fought for its passage to combat what he viewed as dangerous secrecy: “Foreign military sales constitute major foreign policy decisions involving the United States in military activities without sufficient deliberation. This has gotten us into trouble in the past and could easily do so again.”21 These concerns, coming in the wake of widespread anger about the war in Vietnam and the secret bombing of Laos and Cambodia, prompted Congress to reform arms sales policy in an attempt to rein in the White House.

The result of these efforts was the AECA, passed in 1976. The act made four major changes to the process by which the United States sold weapons to foreign nations.22 First, it formalized the executive branch’s lead role in negotiating and approving arms deals, with primary responsibilities divided between the State Department and the Department of Defense. Second, in order to ensure transparency, the act required the White House to notify Congress of impending sales above a certain dollar value. Third, the act required the White House to deliver a politico-military risk assessment of each proposed arms sale to ensure that the national security benefits would outweigh any potential negative consequences. Finally, Congress reserved for itself the ability to block White House arms deals by passing a resolution within 30 days of official notification.23

As with the War Powers Act and other reforms from the 1970s aimed at curbing presidential power, however, the AECA looks more significant on paper than it has proved to be in practice. In reality, the act does very little to limit the White House’s arms sales efforts. Most fundamentally, despite the fact that the Constitution clearly identifies Congress as the lead branch of government with respect to the regulation of foreign commerce, Congress did not give itself a significant enough role in arms sales policy. Rather than structure the process to require active congressional approval of each major deal or to require annual congressional review and approval of ongoing deals, Congress instead abdicated its authority almost entirely.24

A benign explanation is that Congress recognized that, despite problems in the past, effective foreign policy requires a unitary authority such as the president and that the act should not tie the president’s hands too tightly. Another explanation, however, is that Congress has little motivation to play an active role in the arms sales process. In fact, the incentives facing Congress mostly point members toward greater support for arms sales. To stake out public opposition to the president is typically not politically wise, especially for members of the president’s own party. But even for the opposing party, supporting major arms deals is good politics because it helps them look supportive not only of U.S. national security but also of American industry and American jobs. All states and many congressional districts are home to the defense industry; in many districts the defense industry is the dominant corporate presence.25 A senator or representative who speaks out against arms sales thus risks losing the financial support of the defense industry as well as votes in their district. The defense industry lobby, moreover, is extremely active and well connected in Washington, D.C., spending more than $100 million a year on average over the past decade.26 As a result, few in Congress are encouraged to challenge the administration’s arms sales agenda, and Congress relegated itself to the role of rubber stamp. In theory, the AECA allows Congress to block problematic deals at the last minute. But because of the practical and political obstacles involved, Congress has made few efforts to do so and has not passed a resolution blocking an arms deal since the AECA became law.27

Thanks in part to this congressional apathy, the risk assessment requirement has generally not restrained the United States from selling weapons even to countries that should not receive them. On paper, the AECA dictates a reasonable bar for the risk assessment. The law states: “Decisions on issuing export licenses . . . shall take into account whether the export of the article would contribute to an arms race, aid in the development of weapons of mass destruction, support international terrorism, increase the possibility of outbreak or escalation of conflict, or prejudice the development of bilateral or multilateral arms control or nonproliferation agreements or other arrangements.”28

Administrations have also highlighted the importance of avoiding arms sales that would lead to negative outcomes. The most recent presidential directive on arms sales, Barack Obama’s Presidential Policy Directive 27 from January 2014, identifies a host of criteria to be included in risk assessments and declares that “All arms transfer decisions will be guided by a set of criteria that maintains the appropriate balance between legitimate arms transfers to support U.S. national security and that of our allies and partners, and the need for restraint against the transfer of arms that would enhance the military capabilities of hostile states, serve to facilitate human rights abuses or violations of international humanitarian law, or otherwise undermine international security.”29

The track record of U.S. arms sales, however, illustrates that the executive branch often puts little effort into conducting realistic risk assessments. Without the need to worry about congressional oversight, executive branch risk assessments serve more as routine paperwork than serious attempts to weigh the positive and negative consequences of an arms deal. The upshot is that for decades the United States has transferred weapons into situations where it was relatively easy to forecast that the risk of negative consequences was high. In most cases, however, short-term motivations outweighed consideration of longer-term possibilities.

The end of the Cold War signaled another important shift in U.S. arms sales policy. During the Cold War, the United States sold weapons to a relatively close-knit circle of allies and aligned nations.30 With the collapse of the Soviet Union, however, ideology and regime type were no longer obstacles to commerce. Prospects for snapping up market share of the global arms industry and reaping profits powered U.S. arms sales. President Bill Clinton was the first president to incorporate economic justifications into official policy. Clinton’s 1995 directive stated that “the impact on U.S. industry and the defense industrial base” would be a key criterion for his administration’s decisionmaking.31 With the abandonment of previous restrictions, many countries turned to the United States to upgrade their Soviet-era arsenals or to restock stores depleted from fighting civil wars.32 As a result, the United States expanded its customer base well beyond Cold War boundaries. In 1993 alone, for example, the Clinton administration approved a record $36 billion in sales, good for a 72 percent share of the Third World arms market.33

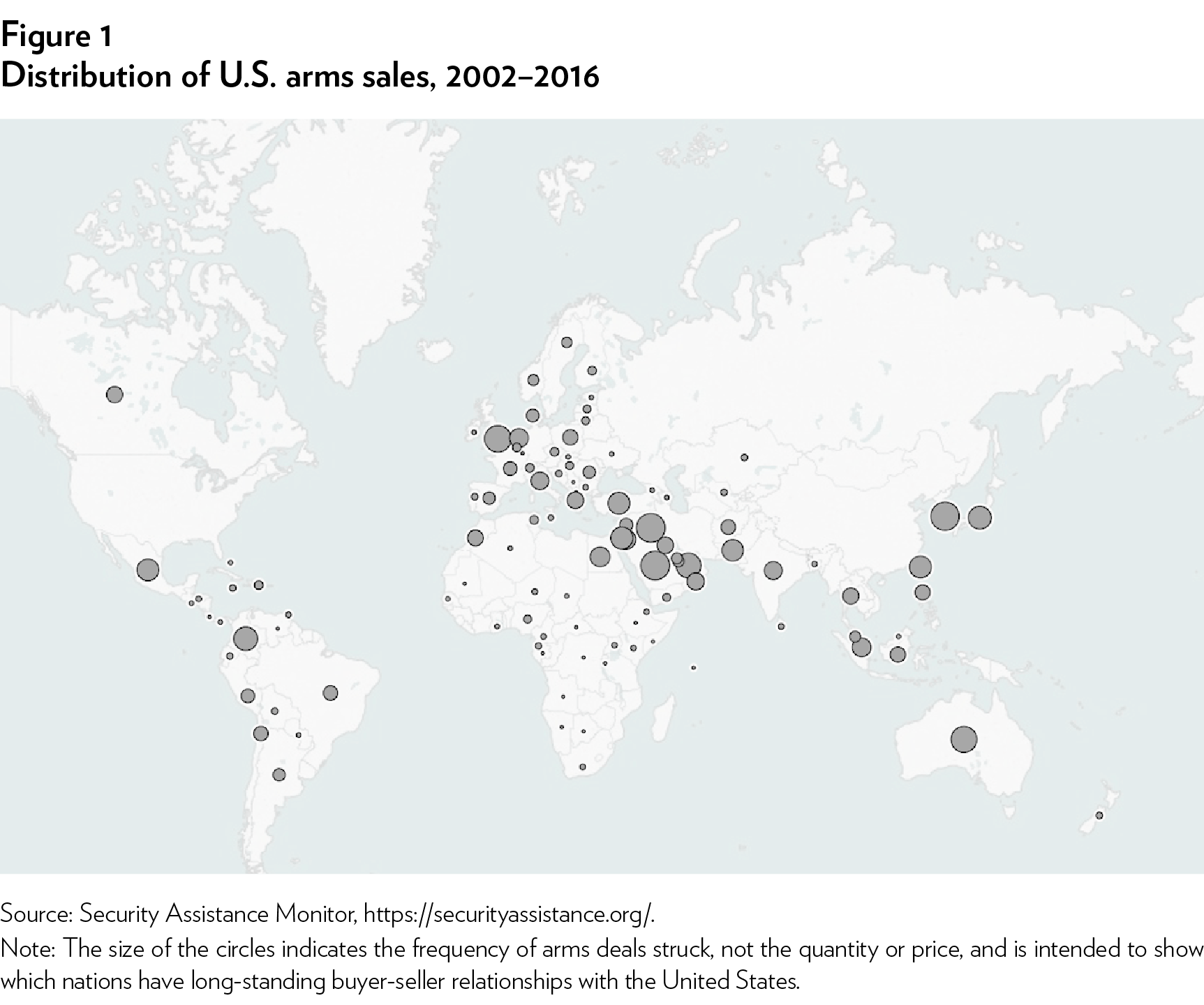

The terrorist attacks of 9/11 marked the most recent inflection point for U.S. arms sales policy. In response to the attacks, both the George W. Bush and Obama administrations oversaw a boom in arms sales, providing foreign governments with unprecedented access to the American arsenal. Since 9/11, the United States has delivered more than $197 billion worth of weapons to 167 countries — not counting Trump’s $110 billion in potential sales to Saudi Arabia, or an additional $84 billion in potential arms sales announced by the administration, to date. Predictably, the urgency of the counterterrorism mission meant that the risk assessment process, never stringent, was weakened further. Nations that had previously been banned from buying American weapons, whether because of human rights violations or their participation in ongoing conflicts, became customers after 9/11, as long as they claimed the weapons would help fight terrorism.34 Both administrations also increased sales to Afghanistan and Iraq, and to a number of other nations in the region, including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and Jordan, on the theory that it would help promote regional stability and aid counterterrorism efforts. During its first year, the Trump administration continued this trend, with an added emphasis on economic opportunities and even less regard for the human rights records of American clients.35 Figure 1 shows the countries that have purchased American weapons since 9/11.

The Case for Arms Sales

Few tools have been used in pursuit of so many foreign policy objectives as arms sales. The United States has sold weapons to its NATO allies to ensure their ability to defend Western Europe; to friendly governments around the world facing insurgencies and organized crime; to allies in the Pacific (buffering them against China’s rising military power); and to both Israel and many of its Arab neighbors in efforts to maintain regional stability and influence over Middle Eastern affairs. The United States has used arms sales, as well as the threat of denying arms, in efforts to influence human rights policies, to help end conflicts, to gain access to military bases, and to encourage fair elections. Since 9/11, the new central focus of U.S. weapons sales has been to bolster the global war on terror.36

Despite their many uses, arms sales impact foreign affairs through two basic mechanisms. The first involves using arms sales to shift the balance of power and capabilities between the recipient and its neighbors, thereby helping allies win wars or deter adversaries, promote local and regional stability, or buttress friendly governments against insurgencies and other internal challenges.37 During the Cold War, American arms sales became part of a broader strategy to deter the Soviet Union from invading Western Europe. In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, the United States sold weapons to Afghanistan and Iraq to bolster their ability to defeat the Taliban, al Qaeda, and the Islamic State. By selling advanced weaponry to Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, and Australia, the United States hoped to balance rising Chinese power and promote regional stability. Although the specific objectives differ, at root the causal mechanism is the same: using arms sales to shift the balance of power in a direction more favorable to American interests.38

The second mechanism involves using arms sales to generate leverage over the conduct of other nations. As the producer of the world’s most advanced and sought-after weaponry, the United States can dictate, at least to some degree, the conditions under which it will agree to sell certain weapons.39 As Andrew Shapiro puts it, “When a country acquires an advanced U.S. defense system, they are not simply buying a product to enhance their security, they are also seeking a relationship with the United States. . . . This engagement helps build bilateral ties and creates strong incentives for recipient countries to maintain good relations with the United States.”40

American influence is thought to be most potent in cases where the United States provides a nation with a large share of its military capabilities. In the wake of U.S. pressure to halt Israeli defense exports to China, for example, an Israeli official acknowledged, “If the United States, which provides Israel with $2 billion in annual military aid, demands that we will not sell anything to China — then we won’t. If the Americans decide we should not be selling arms to other countries as well — Israel will have no choice but to comply.”41

The United States has used arms sales to try to encourage states to vote with the United States at the UN, to support or adopt pro-Western and pro-U.S. foreign policies, to convince Egypt and Israel to accept peace accords, and to gain access to military bases in places such as Greece, Turkey, Kenya, Somalia, Oman, and the Philippines. After the Cold War, the United States also sought to tie arms transfers to human rights and democratization efforts in client states.42

Arms sales remain attractive to presidents for three main reasons. First, arms sales are less risky than sending American troops, providing explicit security guarantees to other nations, or initiating direct military intervention, even long distance.43 In cases where allies or partners are likely to engage in conflicts with their neighbors, providing weapons rather than stationing troops abroad can lessen the risk of American entrapment in crises or conflicts. Taiwan is an example of this sort of arms-for-troops substitution. On the other hand, in instances where the United States has an interest in conflicts already underway, arms sales can be used in attempts to achieve military objectives without putting American soldiers (or at least putting fewer of them) in harm’s way. This tactic has been a central element of the American war on terror, with sales (and outright transfers) of weapons to Afghanistan and Iraq to support the fight against the Taliban, al Qaeda, and ISIS, as well as to Saudi Arabia for its war in Yemen.44 In both situations the reduction of military risk, in particular the risk of American casualties, also helps reduce the political risk. Presidents who would otherwise abstain from supporting a nation if it entailed sending American troops can sell arms to that country without the political fallout that sending America troops abroad would incur.

Second, arms sales are an extremely flexible tool of statecraft. In contrast to the blunt nature of military intervention, or the long-term commitment and convoluted politics that treaties involve, arms sales can take any form from small to large and can take place on a one-time or ongoing basis; they can be ramped up or down and started or stopped relatively quickly, depending on the circumstances. Selling arms to one nation, moreover, does not prohibit the United States from selling arms to any other nation. And thanks to their capacity and prestige, American weapons serve as useful bargaining chips in all sorts of negotiations between the United States and recipient nations.45

Finally, arms sales represent a very low-cost and low-friction policy tool for the White House.46 Unlike military intervention or stationing troops abroad, arms sales are not dependent on defense budgets or on a laborious congressional process. And since most arms deals receive little publicity, presidents don’t have to worry about generating support from the public. As a result, the president can strike an arms deal unilaterally and at any time. Moreover, since most political leaders view arms sales as an economic benefit to the United States, the president tends to receive far more encouragement than pushback on the vast majority of arms deals. Inevitably, the fact that arms sales are low cost and easy to implement means that presidents reach for them frequently, even if they are not necessarily the best tool for the job.

The Case against Arms Sales

Under the right circumstances, we agree that arms sales can be a useful tool of foreign policy. More often, however, we argue that the benefits of U.S. arms sales are too uncertain and too limited to outweigh the negative consequences they often produce. Though presidents like them because they are relatively easy to use, in most cases arms sales are not the best way to achieve U.S. foreign policy objectives. The strategic case for radically reducing arms sales rests on four related arguments. First, arms sales do little to enhance American security. Second, the nonsecurity benefits are far more limited and uncertain than arms sales advocates acknowledge. Third, the negative and unwanted consequences of arms sales are more common and more dangerous than most realize. Finally, the United States would enjoy significant diplomatic benefits from halting arms sales.

Arms Sales Provide Little Direct Benefit to U.S. National Security

At the strategic level, the United States inhabits such an extremely favorable security environment in the post–Cold War world that most arms sales do little or nothing to improve its security. Thanks to its geography, friendly (and weak) neighbors, large and dynamic economy, and secure nuclear arsenal, the United States faces very few significant threats. There is no Soviet Union bent upon dominating Europe and destroying the United States. China, despite its rapid rise, cannot (and has no reason to) challenge the sovereignty or territorial integrity of the United States. Arms sales — to allies or others — are unnecessary to deter major, direct threats to U.S. national security in the current era.47

Nor are arms sales necessary to protect the United States from “falling dominoes,” or the consequences of conflicts elsewhere. The United States enjoys what Eric Nordlinger called “strategic immunity.”48 Simply put, most of what happens in the rest of the world is irrelevant to U.S. national security. The United States has spent decades helping South Korea keep North Korea in check, for example, but division of territory on the Korean peninsula does not affect America’s security. Likewise, civil wars in the Middle East and Russia’s annexation of Crimea might be significant for many reasons, but those events do not threaten the ability of the United States to defend itself. As a result, a decision to sell weapons to Ukraine, Taiwan, or South Korea could significantly affect those nations’ security; doing so is not an act of ensuring U.S. national security.

Nor does the threat of transnational terrorism justify most arms sales. Most fundamentally, the actual threat from Islamist-inspired terrorism to Americans is extraordinarily low. Since 9/11, neither al Qaeda nor the Islamic State has managed an attack on the American homeland. Lone wolf terrorists inspired by those groups have done so, but since 9/11 those attacks have killed fewer than 100 Americans, an average of about 6 people per year. There is simply very little risk reduction to be gained from any strategy. The idea that the United States should be willing to accept the significant negative effects of arms sales for minimal counterterrorism gains is seriously misguided.49

Moreover, even if one believed that the benefits would outweigh the potential costs, arms sales still have almost no value as a tool in the war on terror for several reasons. First, the bulk of arms sales (and those we considered in our risk assessment) involve major conventional weapons, which are ill suited to combatting terrorism. Many U.S. arms deals since 9/11 have involved major conventional weapons systems such as fighter jets, missiles, and artillery, useful for traditional military operations, but of little use in fighting terrorists. Insurgencies that hold territory, like the Islamic State, are one thing, but most terrorist groups do not advertise their location, nor do they assemble in large groups.

Second, there is little evidence from the past 16 years that direct military intervention is the right way to combat terrorism. Research reveals that military force alone “seldom ends terrorism.”50 This comports with the American experience in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere in the war on terror to date. Despite regime change, thousands of air strikes, and efforts to upgrade the military capabilities of friendly governments, the United States has not only failed to destroy the threat of Islamist-inspired terrorism, it has also spawned chaos, greater resentment, and a sharp increase in the level of terrorism afflicting the nations involved.51 Given the experience of the United States since 2001, there is little reason to expect that additional arms sales to countries like Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Qatar, or the United Arab Emirates will reduce terrorism, much less anti-American terrorism specifically.

Relatedly, many arms deals since 9/11, made in the name of counterterrorism, were irrelevant to U.S. goals in the global war on terror because they provided weapons to governments fighting terrorist groups only vaguely (if at all) linked to al Qaeda or ISIS. Although selling weapons to the governments of Nigeria or Morocco or Tunisia might help them combat violent resistance in their countries, terrorist groups in those countries have never targeted the United States. As a result, such arms deals cannot be justified by arguing that they advance the goals of the United States in its own war on terror in any serious way.

Finally, arms sales are completely useless to combat the largest terrorist threat to the U.S. homeland — lone wolf attackers already living in the United States. As noted, none of the successful attacks in the United States since 9/11 resulted from operations directed by al Qaeda or ISIS. And in fact only two foiled attempts since then — the underwear bomber and the printer-bomb plot — can be ascribed to al Qaeda.52 Instead, in almost all cases, persons already living in the United States, inspired by Islamist groups, decided to carry out attacks on their own. Clearly, arms sales to foreign nations won’t help with that problem; rather, as many analysts have suggested, amplifying conflicts abroad may well make the problem worse.53

In sum, the strategic value of arms sales for the United States is very low given today’s security environment. Different circumstances would produce a different analysis. Although today there is little reason for the United States to worry about the Russian threat to Europe, during the Cold War foreign policy experts agreed that preventing the Soviet Union from dominating the European continent was critical to American security. As a result, the United States sensibly provided NATO allies with advanced weapons. This strategy greatly enhanced the fighting capability of NATO, thereby bolstering deterrence and ensuring European security.

Today, happily, the United States faces no such threats. For this reason, the argument in favor of arms sales cannot rest on national security grounds but must rest instead on “national interest” grounds, that is, on the benefits gained from helping other nations improve their own security, and from maintaining conditions generally believed to be in the national interest, such as regional stability or the prevention of war. This is already a much weaker position than the conventional wisdom acknowledges. Even worse for such sales’ advocates, however, is the fact that arms sales are notoriously uncertain tools for achieving those objectives.

The Uncertain and Limited Benefits of Arms Sales

Attempts to manage the balance of power and generate influence around the world are heavily contingent on a number of factors, most of which lie outside American control. Upon closer review, most of the benefits of arms sales are less certain and less compelling than advocates claim.

Managing the Balance of Power: The Illusion of Control. The hidden assumption underlying the balance of power strategy is that the United States will be able to predict accurately what the impact of its arms sales will be. If the goal is deterrence, for example, the assumption is that an arms sale will be sufficient to deter the adversary without spawning an arms race. If the goal is to promote stability, the assumption is that an arms sale will in fact reduce tensions and inhibit conflict rather than inflame tensions and help initiate conflict. These assumptions, in turn, depend on both the recipient nation and that nation’s neighbors and adversaries acting in ways that don’t make things worse.

As it turns out, these are often poor assumptions. Although arms sales certainly enhance the military capability of the recipient nation, the fundamental problem is that arms sales often initiate a long chain of responses that the United States generally cannot control. The United States, after all, is not the only country with interests in regional balances, especially where the survival and security of local actors is at stake. The United States is neither the only major power with a keen interest in critical regions like Asia and the Middle East, nor the only source of weapons and other forms of assistance. Nor can it dictate the perceptions, interests, or actions of the other nations involved in a given region. For example, though a nation receiving arms from the United States may enjoy enhanced defensive capabilities, it is also likely to enjoy enhanced offensive capabilities. With these, a nation’s calculations about the potential benefits of war, intervention abroad, or even the use of force against its own population may shift decisively. Saudi Arabia’s recent behavior illustrates this dynamic. Though the Saudis explain their arms purchases as necessary for defense against Iranian pressure, Saudi Arabia has also spent the past two years embroiled in a military intervention in Yemen.

Likewise, arms sales can heighten regional security dilemmas. Neighbors of nations buying major conventional weapons will also worry about what this enhanced military capability will mean. This raises the chances that they too will seek to arm themselves further, or take other steps to shift the balance of power back in their favor, or, in the extreme case, to launch a preventive war before they are attacked. Given these dynamics, the consequences of arms sales to manage regional balances of power are far less predictable and often much less positive than advocates assume.54

This unpredictability characterizes even straightforward-seeming efforts to manage the balance of power. The most basic claim of arms sales advocates is that U.S. arms sales to friendly governments and allies should make them better able to deter adversaries. The best available evidence, however, suggests a more complicated reality. In a study of arms sales from 1950 to 1995, major-power arms sales to existing allies had no effect on the chance that the recipient would be the target of a military attack. Worse, recipients of U.S. arms that were not treaty allies were significantly more likely to become targets.55

Nor is there much evidence that arms sales can help the United States promote peace and regional stability by calibrating the local balance of power. On this score, in fact, the evidence suggests that the default assumption should be the opposite. Most scholarly work concludes that arms sales exacerbate instability and increase the likelihood of conflict.56 One study, for example, found that during the Cold War, U.S. and Soviet arms sales to hostile dyads (e.g., India/Pakistan, Iran/Iraq, Ethiopia/Somalia) “contributed to hostile political relations and imbalanced military relationships” and were “profoundly destabilizing.”57

There is also good reason to believe that several factors are making the promotion of regional stability through arms sales more difficult. The shrinking U.S. military advantage over other powers such as China and the increasingly competitive global arms market both make it less likely that U.S. arms sales can make a decisive difference. As William Hartung argued as early as 1990, “the notion of using arms transfers to maintain a carefully calibrated regional balance of power seems increasingly archaic in today’s arms market, in which a potential U.S. adversary is as likely to be receiving weapons from U.S. allies like Italy or France as it is from former or current adversaries.”58

In sum, the academic and historical evidence indicates that although the United States can use arms sales to enhance the military capabilities of other nations and thereby shift the local and regional balance of power, its ability to dictate specific outcomes through such efforts is severely limited.

Arms for (Not That Much) Influence. Successful foreign policy involves encouraging other nations to behave in ways that benefit the United States. As noted, the United States has often attempted to use arms sales to generate the sort of leverage or influence necessary to do this. History reveals, however, that the benefits of the arms for influence strategy are limited for two main reasons.

First, the range of cases in which arms sales can produce useful leverage is much narrower than is often imagined. Most obviously, arms sales are unnecessary in situations where the other country already agrees or complies with the American position or can be encouraged to do so without such incentives. This category includes most U.S. allies and close partners under many, though not all, circumstances.

Just as clearly, the arms for influence strategy is a nonstarter when the other state will never agree to comply with American demands. This category includes a small group of obvious cases such as Russia, China, Iran, and other potential adversaries (to which the United States does not sell weapons anyway), but it also includes a much larger group of cases in which the other state opposes what the United States wants, or in which complying with U.S. wishes would be politically too dangerous for that state’s leadership.59

In addition, there are some cases in which the United States itself would view arms sales as an inappropriate tool. The Leahy Law, for example, bars the United States from providing security assistance to any specific foreign military unit deemed responsible for past human rights abuses.60 More broadly, arms sales are clearly a risky choice when the recipient state is a failed state or when it is engaged in a civil conflict or interstate war. Indeed, in such cases it is often unclear whether there is anyone to negotiate with in the first place, and governments are at best on shaky ground. At present the United States bars 17 such nations from purchasing American arms. As long as these nations are embargoed, arms sales will remain an irrelevant option for exerting influence.61

Apart from these cases, there is a large group of nations with tiny defense budgets that simply don’t buy enough major conventional weaponry to provide much incentive for arms sales. On this list are as many as 112 countries that purchased less than $100 million in arms from the United States between 2002 and 2016, including Venezuela, Jamaica, and Sudan. Lest this category be dismissed because it includes mostly smaller and less strategically significant countries from the American perspective, it should be noted that each of these countries has a vote in the United Nations (and other international organizations) and that many of them suffer from civil conflicts and terrorism, making them potential targets of interest for American policymakers looking for international influence.

By definition, then, the arms-for-influence strategy is limited to cases in which a currently noncompliant country might be willing to change its policies (at least for the right price or to avoid punishment).

The second problem with the arms for influence strategy is that international pressure in general, whether in the form of economic sanctions, arms sales and embargoes, or military and foreign aid promises and threats, typically has a very limited impact on state behavior. Though again, on paper, the logic of both coercion and buying compliance looks straightforward, research shows that leaders make decisions on the basis of factors other than just the national balance sheet. In particular, leaders tend to respond far more to concerns about national security and their own regime security than they do to external pressure. Arms sales, whether used as carrots or sticks, are in effect a fairly weak version of economic sanctions, which research has shown have limited effects, even when approved by the United Nations, and tend to spawn a host of unintended consequences. As such, the expectations for their utility should be even more limited.62 A recent study regarding the impact of economic sanctions came to a similar conclusion, noting that, “The economic impact of sanctions may be pronounced . . . but other factors in the situational context almost always overshadow the impact of sanctions in determining the political outcome.”63 The authors of another study evaluating the impact of military aid concur, arguing that, “In general we find that military aid does not lead to more cooperative behavior on the part of the recipient state. With limited exceptions, increasing levels of U.S. aid are linked to a significant reduction in cooperative foreign policy behavior.”64

Perhaps the most explicit evidence of the difficulty the United States has had exerting this kind of leverage came during the Reagan administration. Sen. Robert Kasten Jr. (R-WI) signaled the concern of many when he said, “Many countries to whom we dispense aid continue to thumb their noses at us” at the United Nations, and Congress passed legislation authorizing the president to limit aid to any state that repeatedly voted in opposition to the United States at the UN.65 In 1986, the Reagan administration began to monitor voting patterns and issue threats, and, in roughly 20 cases in 1987 and 1988, it lowered the amount of aid sent to nations the administration felt were not deferential enough. An analysis of the results, however, found no linkage between changes in American support and UN voting patterns by recipient states. The authors’ conclusion fits neatly within the broader literature about the limited impact of sanctions: “The resilience of aid recipients clearly demonstrates that their policies were driven more powerfully by interests other than the economic threat of a hegemon.”66

The U.S. track record of generating influence through arms sales specifically is quite mixed. U.S. arms sales may have improved Israeli security over the years, for example, but American attempts to pressure Israel into negotiating a durable peace settlement with the Palestinians have had little impact. Nor have arms sales provided the United States with enough leverage over the years to prevent client states such as Iraq, Iran, Turkey, Indonesia, and Morocco from invading their neighbors. Nor have arms sales helped restrain the human rights abuses of clients like Chile or Libya, or various Middle Eastern client states. Although the United States has used the promise of arms sales or the threat of denying arms successfully from time to time, the failures outnumber the victories. The most rigorous study conducted to tease out the conditions under which arms for influence efforts are successful is a 1994 study by John Sislin.67 Collating 191 attempts between 1950 and 1992, Sislin codes 80 of those attempts (42 percent) successful. Sislin’s analysis is incomplete, however, since he looks only at the immediate benefits of arms sales and does not consider the long-term consequences.

Furthermore, a close look at the supposedly successful attempts reveals that many of them are cases in which the United States is in fact simply buying something rather than actually “influencing” another nation. Thirty of the cases Sislin coded as successful were instances of the United States using arms to buy access to military bases (20 cases) or to raw materials (5 cases) or to encourage countries to buy more American weapons (5 cases).68 Without those in the dataset, the U.S. success rate drops to 31 percent.

Finally, the conditions for successful leverage seeking appear to be deteriorating. First, Sislin’s study found that American influence was at its height during the Cold War when American power overshadowed the rest of the world. With the leveling out of the global distribution of power, both economic and military, the ability of the United States to exert influence has waned, regardless of the specific tool being used. Second, as noted above, the U.S. share of the global arms market has declined as the industry has become more competitive and, as a result, American promises and threats carry less weight than before. As William Hartung noted, “The odds [of] buying political loyalty via arms transfers are incalculably higher [worse] in a world in which there are dozens of nations to turn to in shopping for major combat equipment.”69

Arms Sales Have Many Potential Negative Consequences

Though arms sales are of marginal value to national security and the pursuit of national interests, their negative consequences are varied and often severe. Arms sales can spawn unwanted outcomes on three levels: blowback against the United States and entanglement in conflicts; regional consequences in the buyer’s neighborhood, such as the dispersion of weapons and increased instability; and consequences for the buyer itself, such as increased levels of corruption, human rights abuses, and civil conflict.

Effects on the United States. Though the goal of arms sales is to promote American security and U.S. interests abroad, at least two possible outcomes can cause serious consequences for the United States. The first of these — blowback — occurs when a former ally turns into an adversary and uses the weapons against the United States. The second — entanglement — is a process whereby an arms sales relationship draws the United States into a greater level of unwanted intervention.

Blowback. The fact that the United States has sold weapons to almost every nation on earth, combined with frequent military intervention, means that blowback is an inescapable outcome of U.S. arms sales policy. American troops and their allies have faced American-made weapons in almost every military engagement since the end of the Cold War, including in Panama, Haiti, Somalia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, and Syria. And even where the United States has not yet engaged in combat, American arms sales have bolstered the military capabilities of adversaries once counted as friendly.

Blowback can occur in at least three ways. First, a previously friendly regime becomes unfriendly. For example, the United States sold billions of dollars in weapons to the Shah of Iran during the 1970s in the hopes that Iran would provide a stabilizing influence on the Middle East. The sales included everything from fighter jets for air campaigns to surface-to-air missiles to shoot down enemy fighters.70 After the 1979 revolution, however, Iran used those weapons in its war with Iraq and enabled the new Iranian regime to exert its influence in the region. Panama, the recipient of decades of American military assistance, as well as host to a major military base and 9,000 U.S. troops, was a similar case. In 1989, Gen. Manuel Noriega — himself a CIA asset for more than 20 years — took power and threatened U.S. citizens, prompting a U.S. invasion that featured American troops facing American weapons.71

Blowback also occurs when the United States sells weapons to nations (or transfers them to nonstate actors) that, though not allies, simply did not register as potential adversaries at the time of the sale. The United States, for example, sold surface-to-air missiles, towed guns, tanks, and armored personnel carriers to Somalia during the 1980s. Few officials would have imagined that the United States would find itself intervening in Somalia in 1992, or that the United States and its allies would provide billions in weapons and dual-use equipment to Iraq in an effort to balance against Iran, only to wind up confronting Iraq on the battlefield to reverse its annexation of Kuwait.72

And finally, blowback can occur when U.S. weapons are sold or stolen from the government that bought them and wind up on the battlefield in the hands of the adversary. For example, the Reagan administration covertly provided Stinger missiles to the Mujahideen, who were fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan during the 1980s; they in turn sold them off eventually to Iran and North Korea, among others. More recently, the Islamic State managed to capture from the Iraqi government a stunning number of Humvees and tanks the United States had sold to Iraq to rebuild its military capabilities after the 2003 invasion, as well as enough small arms and ammunition to supply three divisions of a conventional army.73

These examples of blowback demonstrate how difficult it can be to forecast the long-term outcomes of arms sales and how obvious it is that selling weapons carries a number of risks. Predicting what exactly will happen is hard, but predicting that arms sales to clients with red flags are likely to end badly is quite easy. Iraq was a fragile state ravaged by a decade’s worth of American intervention and rife with terrorism and civil conflict; to transfer such large quantities of weapons to its military and police force under such conditions was to invite disaster.

Entanglement. Arms sales raise the risk of entanglement in two ways. First, they can represent early steps down the slippery slope to unwise military intervention. Consider a case like the Syrian civil war or the many cases during the Cold War in which the United States wanted to support rebels and freedom fighters against oppressive governments.74 In the majority of those cases, American leaders were wary of intervening directly. Instead, the United States tended to rely on money, training, and arms sales. But by taking concrete steps like arms sales to support rebel groups, Washington’s psychological investment in the outcome tends to rise, as do the political stakes for the president, who will be judged on whether his efforts at support are successful or not. As we saw in the Syrian civil war, for example, Barack Obama’s early efforts to arm Syrian rebels were roundly criticized as feckless, increasing pressure on him to intervene more seriously.75

History does not provide much guidance about how serious the risk of this form of entanglement might be. During the Cold War, presidents from Nixon onward viewed arms sales as a substitute for sending American troops to do battle with communist forces around the world. The result was an astonishing amount of weaponry transferred or sold to Third World nations, many of which were engaged in active conflicts both external and internal. The risk of superpower conflict made it dangerous to intervene directly; accordingly, the Cold War–era risk of entanglement from arms sales was low.76 Today, however, the United States does not face nearly as many constraints on its behavior, as its track record of near-constant military intervention since the end of the Cold War indicates. As a result, the risk of arms sales helping trigger future military intervention is real, even if it cannot be measured precisely.

The second way in which arms sales might entangle the United States is by creating new disputes or exacerbating existing tensions. U.S. arms sales to Kurdish units fighting in Syria against the Islamic State, for example, have ignited tensions between the United States and its NATO ally Turkey, which sees the Kurds as a serious threat to Turkish sovereignty and stability.77 Meanwhile, ongoing arms sales to NATO nations and to other allies like South Korea and Taiwan have exacerbated tensions with Russia, China, and North Korea, raising the risk of escalation and the possibility that the United States might wind up involved in a direct conflict.78

Regional Effects. Arms sales do not just affect the recipient nation; they also affect the local balance of power, often causing ripple effects throughout the region. Though advocates of arms sales trumpet their stabilizing influence, as we have noted above, arms sales often lead to greater tension, less stability, and more conflict. Because of this — and the complementary problem of weapons dispersion — the regional impact of arms sales is less predictable and more problematic than advocates acknowledge.

Instability, Violence, and Conflict. First, arms sales can make conflict more likely.79 This may occur because recipients of new weapons feel more confident about launching attacks or because changes in the local balance of power can fuel tensions and promote preventive strikes by others. A study of arms sales from 1950 to 1995, for example, found that although arms sales appeared to have some restraining effect on major-power allies, they had the opposite effect in other cases, and concluded that “increased arms transfers from major powers make states significantly more likely to be militarized dispute initiators.”80 Another study focused on sub-Saharan Africa from 1967 to 1997 found that “arms transfers are significant and positive predictors of increased probability of war.”81 Recent history provides supporting evidence for these findings: since 2011, Saudi Arabia, the leading buyer of American weapons, has intervened to varying degrees in Yemen, Tunisia, Syria, and Qatar.

Second, arms sales can also prolong and intensify ongoing conflicts and erode rather than promote regional stability. Few governments, and fewer insurgencies, have large enough weapons stocks to fight for long without resupply.82 The tendency of external powers to arm the side they support, however understandable strategically, has the inevitable result of allowing the conflict to continue at a higher level of intensity than would otherwise be the case. As one study of arms sales to Africa notes, “Weapons imports are essential additives in this recipe for armed conflict and carnage.”83

Third, this dynamic appears to be particularly troublesome with respect to internal conflicts. Jennifer Erickson, for example, found that recipients of major conventional weapons are 70 percent more likely to engage in internal conflicts than other states. Though halting arms sales alone is not a panacea for peace and stability, arms embargoes can help lessen the destructiveness of combat in both civil and interstate wars simply by restricting access to the means of violence.84

Finally, because of their effects on both interstate and internal conflict, arms sales can also erode rather than promote regional stability. As noted in the previous section, where the United States seeks to manage regional balances of power, arms sales often create tension, whether because the American role in the region threatens others or because American clients feel emboldened. The Middle East, for example, has seesawed between violence and tense standoffs for the past many decades, at first because of Cold War competition and more recently because of the American war on terror. The notion that increased U.S. arms sales since 9/11 made the Middle East more stable is far-fetched to say the least. Similarly, though many argue that American security commitments to countries like Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea have produced greater stability, there is a strong case to be made that the opposite is now true. American support of South Korea has driven North Korea to develop nuclear weapons; the presence of U.S. missile defense systems in South Korea has aggravated China, and American support of Taiwan produces continual tension between the two powers.85

Dispersion. The United States uses a number of procedures to try to ensure that the weapons it sells actually go to authorized customers and to monitor the end use of the weapons so that they do not wind up being used for nefarious purposes. The Department of State even compiles a list of banned countries, brokers, and customers. But most of these tools have proved ineffectual.86

Programs like Blue Lantern and Golden Sentry aim to shed light on the service life of American weapons sold abroad through end-use monitoring.87 While the description of U.S. end-use monitoring (“pre-license, post-license/pre-shipment, and post-shipment”) sounds comprehensive, it’s actually anything but. In fiscal year 2016, the agency in charge of approving and monitoring arms sales, the Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC), authorized 38,398 export-license applications — down more than 50 percent from 2012 after the government shifted some weapons to the Department of Commerce’s purview.88 To oversee more than 35,000 export licenses annually, the DDTC has a full-time staff of only 171 people. The Blue Lantern program is executed by embassy staff in recipient countries but administered back in Washington by only nine State Department employees and three contractors.89 Twelve people can’t possibly track everything that happens to billions of dollars’ worth of advanced weaponry transferred to dozens of countries abroad each year.

Nor is the process designed to correct problems. On one hand, end-use violations can result in individuals and companies being prevented from making future purchases. On the other hand, there is no evidence that end-use monitoring has changed the pattern of American arms sales in any way. The United States in truth has little or no control over what happens to the weapons it sells to other nations. The result is that year after year weapons of all kinds end up falling into the hands of unreliable, risky, or just plain bad actors, at which point they’re used in ways neither the United States nor its customers intended. American weapons have frequently wound up being used against Americans in combat. And even more often, local and regional actors, including criminal gangs, have employed them in their own conflicts. In civil wars, regime collapse, or other extreme cases, factions steal weapons and use them for their own purposes, as ISIS did in Iraq.90

Iraq, as previously noted, provides an excellent case study in the inability of the United States to prevent dispersion. As part of U.S. efforts to rebuild Iraq’s military and security capabilities after the 2003 invasion, the United States sent Iraq roughly $2.5 billion worth of American weapons through 2014, including everything from small arms to “armored personnel carriers, military helicopters, transport aircraft, anti-tank missiles, tanks, artillery and drones.” 91

Despite the presence of thousands of U.S. troops in-country and the very close relationship between those troops and their Iraqi counterparts, many of those weapons went missing. Between 2003 and 2008 alone, 360,000 out of 1 million small arms disappeared, along with 2,300 Humvees. A sizable chunk of this weaponry would later end up in the hands of ISIS. The Iraqi army, trained and equipped by the American military, dissolved when faced by ISIS and left their weapons behind for the terrorist group to pick up and use for conquering and holding territory. A UN Security Council report found that in June 2014 alone “ISIS seized sufficient Iraqi government stocks from the provinces of Anbar and Salah al-Din to arm and equip more than three Iraqi conventional army divisions.”92 Data collected by Conflict Armament Research in July and August of 2014 showed that 20 percent of ISIS’s ammunition was manufactured in the United States — likely seized from Iraqi military stocks.93 In short, dispersion enabled the spread of ISIS and dramatically raised the costs and dangers of confronting the group on the battlefield.

Regime Effects. Finally, arms sales can also have deleterious effects on recipient nations — promoting government oppression, instability, and military coups. As part of the war on drugs, America inadvertently enabled the practice of forced disappearances. In the cases of Colombia, the Philippines, and Mexico, American weapons feed a dangerous cycle of corruption and oppression involving the police, the military, and political leaders.94 Though the United States provides weapons to Mexico ostensibly for counternarcotics operations, the arms transferred to the country often end up being used by police to oppress citizens, reinforcing the “climate of generalized violence in the country [that] carries with it grave consequences for the rule of law.”95 Similarly, in Colombia and the Philippines the United States has supplied arms in an effort to support governments against external threats or internal factions and to combat drug trafficking, but with mixed results. A study of military aid to Colombia found that “in environments such as Colombia, international military assistance can strengthen armed nonstate actors, who rival the government over the use of violence.”96

Recent research reveals that American assistance programs, like foreign military officer training, can increase the likelihood of military coups. U.S. training programs frequently bought by other nations, most notably International Military Education and Training (IMET), gave formal training to the leaders of the 2009 Honduran coup, the 2012 Mali coup, and the 2013 Egyptian coup.97 In these cases, the training that was supposed to stabilize the country provided military leaders with the tools to overthrow the government they were meant to support.

The Case for a New Approach

So far we have argued that arms sales lack a compelling strategic justification, amplify risks, and generate a host of unintended negative consequences. These factors alone argue for significantly curtailing the arms trade. But the case for doing so is made even stronger by the fact that greatly reducing arms sales would also produce two significant benefits for the United States that cannot otherwise be enjoyed.

The first benefit from reducing arms sales would be greater diplomatic flexibility and leverage. Critics might argue that even if arms sales are an imperfect tool, forgoing arms sales will eliminate a potential source of leverage. We argue that, on the contrary, the diplomatic gains from forgoing arms sales will outweigh the potential leverage or other benefits from arms sales. Most importantly, by refraining from arming nations engaged in conflict, the United States will have the diplomatic flexibility to engage with all parties as an honest broker. The inherent difficulty of negotiating while arming one side is obvious today with respect to North and South Korea. After decades of U.S. support for South Korea, North Korea clearly does not trust the United States. Similarly, U.S. attempts to help negotiate a peace deal between the Israelis and Palestinians have long been complicated by American support for Israel. To stop arming one side of a contentious relationship is not to suggest that the United States does not have a preferred outcome in such cases. Rather, by staying out of the military domain the United States can more readily encourage dialogue and diplomacy.

Forgoing arms sales is likely to be a superior strategy even in cases where the United States has an entrenched interest. In the case of Taiwan, for example, though it is clear that Taiwan needs to purchase weapons from other countries to provide for its defense, those weapons do not have to be made in the United States. Having Taiwan buy from other suppliers would help defuse U.S.–China tensions. Even if Taiwan’s defenses remained robust, China would clearly prefer a situation in which American arms no longer signal an implicit promise to fight on Taiwan’s behalf. This could also promote more productive U.S.–China diplomacy in general, as well as greater stability in the Pacific region. Most important, breaking off arms sales would also reduce the likelihood of the United States becoming entangled in a future conflict between Taiwan and China.

The second major benefit of reducing arms sales is that it would imbue the United States with greater moral authority. Today, as the leading arms-dealing nation in the world, the United States lacks credibility in discussions of arms control and nonproliferation, especially in light of its military interventionism since 2001. By showing the world that it is ready to choose diplomacy over the arms trade, the United States would provide a huge boost to international efforts to curtail proliferation and its negative consequences. This is important because the United States has pursued and will continue to pursue a wide range of arms control and nonproliferation objectives. The United States is a signatory of treaties dealing with weapons of mass destruction, missile technology, land mines, and cluster munitions, not to mention the flow of conventional weapons of all kinds. The effectiveness of these treaties, and the ability to create more effective and enduring arms control and nonproliferation frameworks, however, depends on how the United States behaves.

This is not to say that unilateral American action will put an end to the problems of the global arms trade. States would still seek to ensure their security and survival through deterrence and military strength. Other weapons suppliers would, in the short run, certainly race to meet the demand. But history shows that global nonproliferation treaties and weapons bans typically require great-power support. In 1969, for example, Richard Nixon decided to shutter the American offensive-biological-weapons program and seek an international ban on such weapons. By 1972 the Biological Weapons Convention passed and has since been signed by 178 nations.98 In 1991 President George H. W. Bush unilaterally renounced the use of chemical weapons. By 1993 the United States had signed the Chemical Weapons Convention, which now has 192 signatories.99 Both of these efforts succeeded in part because the United States took decisive early action in the absence of any promises about how others would respond.100 Without U.S. leadership, any effort to limit proliferation of major conventional weapons and dangerous emerging technologies is likely to fail.

Policy Recommendations

The United States should reorient its arms sales policy to ensure that sales provide strategic benefits and to avoid producing negative unintended consequences. At a practical level, this means reducing arms sales dramatically, especially to nations with high risk factors for negative outcomes. Officials should look for other ways to conduct foreign policy in situations where arms sales have been common tactics — such as when the United States negotiates access to military bases or seeks cooperation in the war on terror. The arms sales process should also be revised in order to ensure that all sales receive more thorough scrutiny than has been the case to date.

To implement this new vision for arms sales we recommend the following steps:

- Issue an Updated Presidential Policy Directive on Arms Sales — Most importantly, the president should issue a new Presidential Policy Directive reorienting U.S. arms sales policy so that the new default policy is “no sale.” The only circumstances in which the United States should sell or transfer arms to another country are when three conditions are met: (1) there is a direct threat to American national security; (2) there is no other way to confront that threat other than arming another country; and (3) the United States is the only potential supplier of the necessary weapons.

The reasoning behind this recommendation is threefold: first, as noted, the United States enjoys such a high level of strategic immunity that there is currently no direct security rationale for arms sales to any nation. Second, even if one believes that the United States has an interest in helping other nations defend themselves against internal enemies (e.g., Iraq, Afghanistan) or external ones (e.g., South Korea, Taiwan, NATO countries), there are other ways the United States can help instead of supplying weapons. Finally, by halting the sales of weapons the United States will decrease the risk of entanglement in conflicts that do not directly involve American security. It will also improve the diplomatic flexibility of the United States to play the role of honest broker and to exert moral leverage on dueling parties.

- Immediately Stop Selling Weapons to Risky Nations — The first step in implementing a new approach should be to stop selling weapons to the countries most likely to misuse weapons or to lose control of them. Based on the risk assessment described here, we recommend that the United States immediately halt the sale of weapons to any nation that scored in the “highest risk” category for any risk factor, or which is actively engaged in conflict. Taking this action would immediately add 71 nations to the list of embargoed nations until further notice. This simple and commonsense step would mitigate some of the worst negative consequences and stop the United States from enabling conflicts abroad.

- Improve and Respond to End-Use Monitoring — The United States should significantly expand its tracking of the use and misuse of American weapons. The current system of end-use monitoring does not collect enough data on how weapons are used once they are transferred. This is largely because the system is designed to monitor and prevent instances of dispersion and corruption and is not necessarily focused on the use of force by the client military and government. Rather than focusing on tracking abuse down to a single military unit, end-use monitoring should hold countries accountable for the actions of their militaries as a whole. End-use monitoring should take into account the bigger picture of a country’s strategic environment and should assess weapons sales based on a proposed customer’s history, actions, and participation in ongoing conflicts. End-use monitoring should be tracked and reported annually, and the results should be made public to enforce oversight and give Congress the information needed to make better-informed decisions.