The Civil Rights Movement was a citizens’ rebellion against one of the longest, most brutal episodes of oppression the United States has seen.

Nearly 100 years after the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution supposedly made African-Americans free and equal citizens and guaranteed them the right to vote, Southern states denied African-Americans the most basic protection governments owe their citizens—protection of bodily integrity—as well as their rights to speak, protest, vote, work, exchange, travel, and marry. Government officials routinely used violence against black Americans who tried to claim equal status or equal protection of the laws. Government officials tolerated and even encouraged groups of white racists that terrorized and murdered black Americans. White majorities in Southern states denied African-Americans the right to vote precisely because allowing blacks to vote would threaten this deliberate system of apartheid. Not unimportantly, this system also violated the rights of other Americans to marry, work, exchange, and travel with African-Americans.

The Civil Rights Movement, whose goal was to enforce the rights of all Americans to be secure in their persons, to vote, to work, to exchange, to travel, and to marry, was a libertarian force. It did more to advance freedom within the United States than any other movement in the past century.

One of the last surviving leaders of the Civil Rights Movement is John Lewis of Georgia.

John Lewis’ Contributions to Human Freedom

John Lewis has made courageous and principled contributions to human freedom. He has been a libertarian force in his campaigns for individual rights, his advocacy for freedom in moral terms, his commitment to peaceful protest, and his fight to save American society from the forces of savagery.

Few in the libertarian movement have suffered as much as Lewis for the cause of freedom. Lewis offered his voice and his body—and sacrificed his right to self-defense—to make Americans confront the violence inherent in the Southern system of government-imposed white-supremacist tyranny.

In the early 1960s, Lewis was sacrificing his body and liberty to protest laws restricting the freedoms of movement, association, and exchange. As an undergraduate at Fisk University in Nashville, Lewis organized non-violent sit-ins at segregated lunch counters

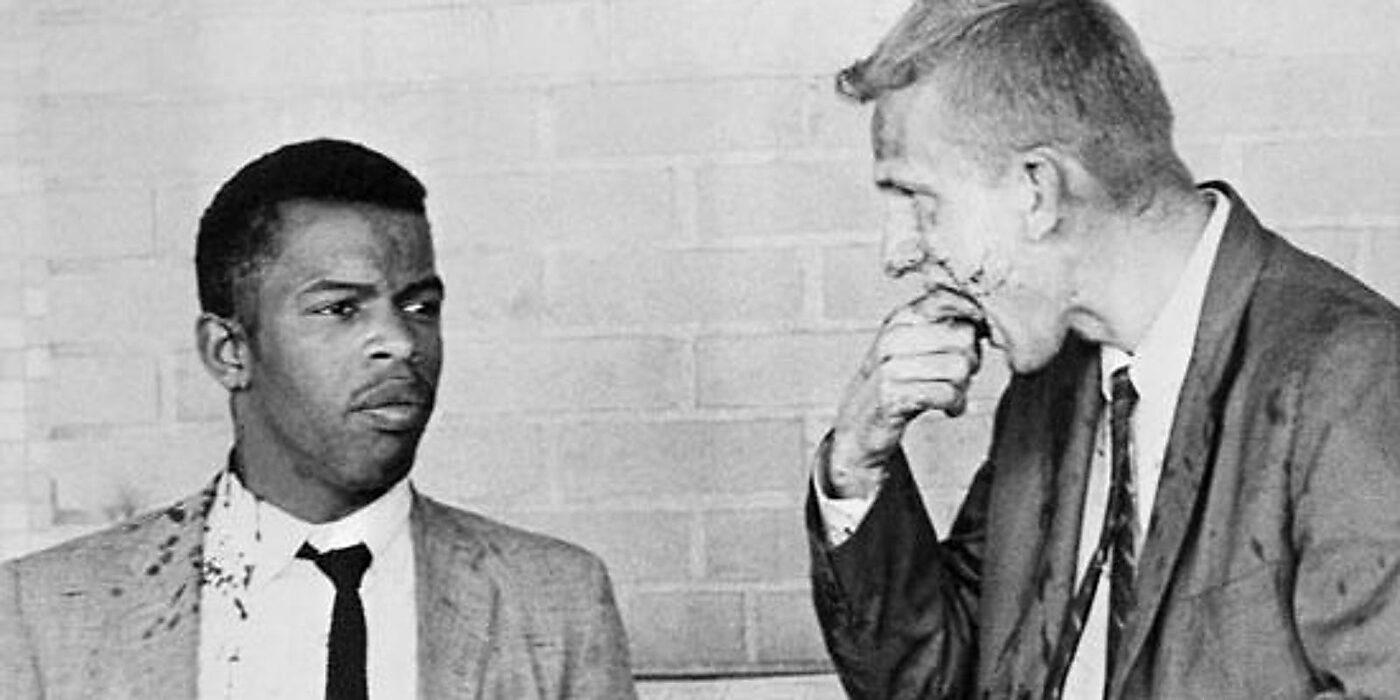

Photo: The Tennessean

As a Freedom Rider, Lewis spent years putting himself in danger to protest laws prohibiting blacks and whites from sitting beside each other on public transportation. He was the first Freedom Rider to encounter violence by white supremacists, who bludgeoned him on multiple occasions. Smithsonian magazine reports that in 1961:

While trying to enter a whites-only waiting room in Rock Hill, South Carolina, two men set upon [Lewis], battering his face and kicking him in the ribs. Less than two weeks later, Lewis joined a ride bound for Jackson.

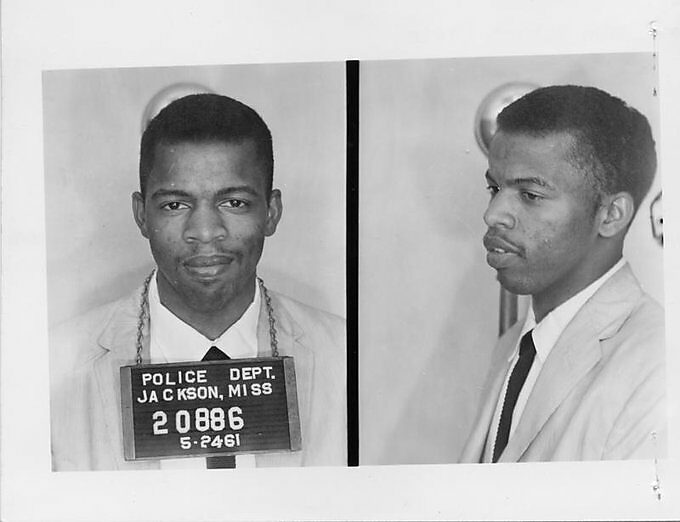

(Birmingham Public Library)

Photo: AP Photo / The Tennessean

As Lewis later explained, the violence followed them across the South:

It was very violent. It was 13 of us on the original ride—seven whites and six blacks…

We were beaten in Birmingham, and later met by an angry mob in Montgomery, where I was hit in the head with a wooden crate. It was very violent. I thought I was going to die. I was left lying at the Greyhound bus station in Montgomery unconscious.

In 1961, Lewis spent 37 days in Mississippi’s Parchman Penitentiary after his arrest for violating a segregation law. He had used a whites-only restroom.

@repjohnlewis via Twitter

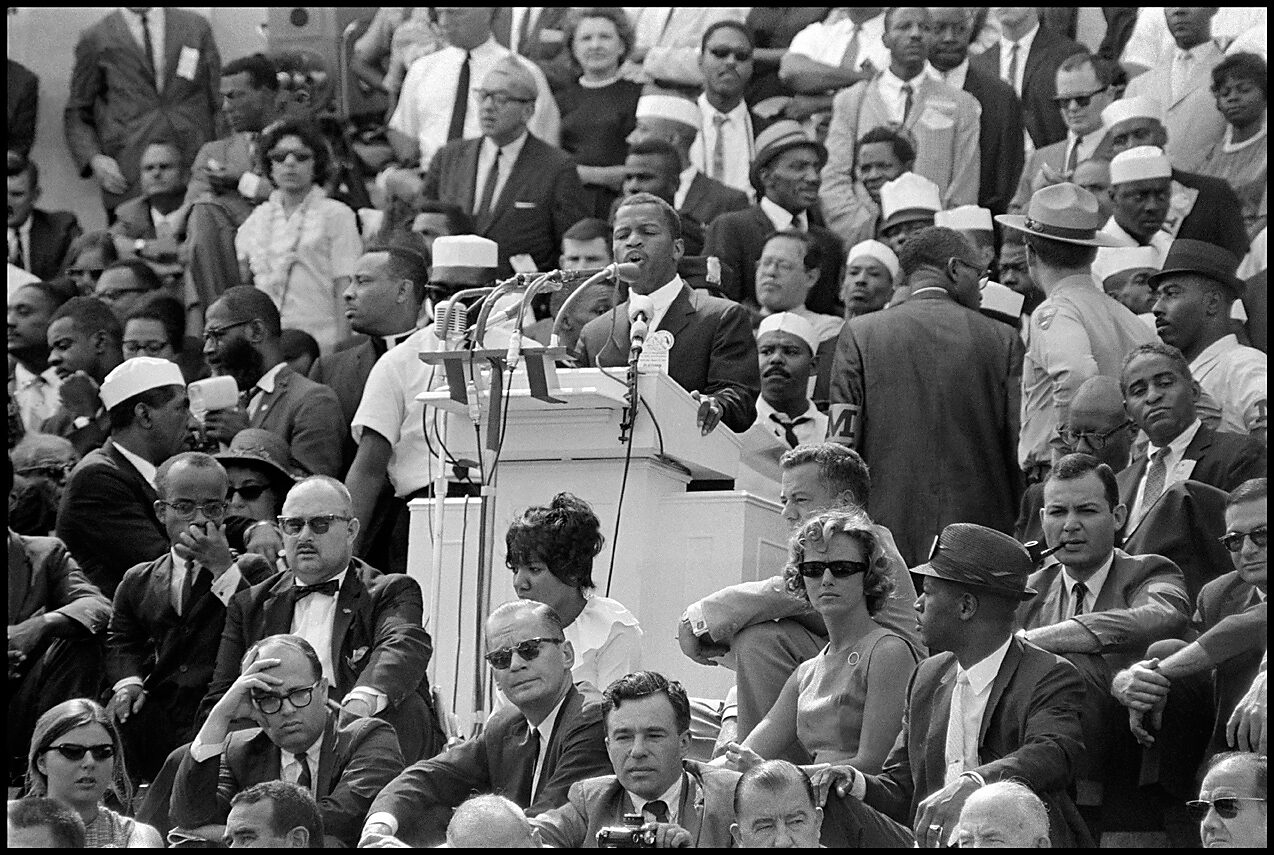

On August 28, 1963, Lewis at the age of 23 was the youngest speaker at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

He was the most forceful of the day’s speakers in demanding freedom for African-Americans. In terms that will be familiar to libertarians, he implored his countrymen to fight the tyranny under which African-Americans lived, and called on them to fulfill the ideals of the American Revolution:

While we stand here there are students in jail on trumped-up charges. Our brother James Farmer, along with many others, is also in jail…

It is true that we support the administration’s civil rights bill. We support it with great reservations, however. Unless [Congress strengthens the bill], there is nothing to protect the young children and old women who must face police dogs and fire hoses in the South while they engage in peaceful demonstrations. In its present form, this bill will not protect the citizens of Danville, Virginia, who must live in constant fear of a police state. It will not protect the hundreds and thousands of people that have been arrested on trumped charges. What about the three young men, SNCC field secretaries in Americus, Georgia, who face the death penalty for engaging in peaceful protest?…

By and large, American politics is dominated by politicians who build their careers on immoral compromises and ally themselves with open forms of political, economic, and social exploitation…

Where is the political party that will make it unnecessary to march in the streets of Birmingham? Where is the political party that will protect the citizens of Albany, Georgia? Do you know that in Albany, Georgia, nine of our leaders have been indicted, not by the Dixiecrats, but by the federal government for peaceful protest? But what did the federal government do when Albany’s deputy sheriff beat Attorney C.B. King and left him half-dead? What did the federal government do when local police officials kicked and assaulted the pregnant wife of Slater King, and she lost her baby?…

We do not want our freedom gradually, but we want to be free now! We are tired. We are tired of being beaten by policemen. We are tired of seeing our people locked up in jail over and over again. And then you holler, “Be patient.” How long can we be patient? We want our freedom and we want it now. We do not want to go to jail. But we will go to jail if this is the price we must pay for love, brotherhood, and true peace.

I appeal to all of you to get into this great revolution that is sweeping this nation. Get in and stay in the streets of every city, every village and hamlet of this nation until true freedom comes, until the revolution of 1776 is complete.

In 1964, Lewis organized voter-registration drives as part of the Mississippi Freedom Summer. Lewis sought to register previously disenfranchised black voters because he knew, as Friedrich Hayek explained, “democracy…is an obstacle to the suppression of freedom.”

On March 7, 1965, Lewis led a peaceful march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. The purpose of the march was to secure voting rights for African-Americans, in the hope of ending government tyranny against blacks.

Historians call that date “Bloody Sunday” because government agents, including many on horses, attacked the peaceful demonstrators with tear gas and billy clubs. An Alabama policeman fractured Lewis’ skull.

Various government agents arrested and imprisoned Lewis more than 40 times for peacefully protesting tyranny. Lewis watched government agents and domestic terrorists kill his friends, colleagues, political patrons, and mentors. Lewis knew these men would never face prosecution.

Yet Lewis never responded with violence. He had a right to use violence to defend himself. He set aside that right to bring freedom to others.

Instead, Lewis has demonstrated civility, magnanimity, and forgiveness toward his oppressors. Decades after two men assaulted him in that South Carolina waiting room, one of them apologized to him. Lewis did something he didn’t have to do. He graciously accepted his assailant’s apology:

“I’m so sorry about what happened back then,” [Elwin] Wilson said breathlessly.

“It’s okay. I forgive you,” Lewis responded before a long-awaited hug.

Lewis has advanced other libertarian causes. He peacefully protested South Africa’s policy of racial apartheid, leading to two arrests outside that nation’s embassy in Washington, D.C. He peacefully protested Sudan’s genocide in Darfur, leading to two arrests outside the Sudanese embassy. He has protested the Iraq War, introducing legislation to postpone tax cuts until the United States ends its wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has protested in favor of immigrant rights, leading to his arrest near the U.S. Capitol.

Weighing Lewis’ Contributions

Some libertarians will protest that Lewis has taken un-libertarian positions over the course of his career. I certainly disagree with many of his positions.

Yet libertarians routinely venerate the words and accomplishments of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and George Mason, even though these men enslaved other humans. Libertarians honor these men not because they are perfect, but because these imperfect men moved their imperfect world in the direction of greater freedom.

Lewis’ contributions to human freedom likewise far outweigh his imperfections. If libertarians can honor Founding Fathers who participated in “the most oppressive dominion ever exercised by man over man,” we can honor John Lewis even though he supports single-payer health care.

In May, the Cato Institute will present its 10th biennial Milton Friedman Prize for Advancing Liberty. If I were on the selection committee, my vote would go to John Lewis.

Show a Little Love

Libertarians often wonder why our movement is not broader or more diverse. One reason might be that it has yet to honor the libertarian goals and successes of the Civil Rights Movement, or the sacrifices its participants made.

Libertarians often claim, for example, that Americans are less free now than they were 100 years ago, when the federal government was smaller. Such claims either ignore or undervalue the tremendous gains in freedom African-Americans have seen over that time. When we casually elide the oppression others have suffered, they tend to notice. John Lewis was a driving force behind those gains.

Lewis struggled long and hard to secure for African-Americans freedoms that most white Americans never lacked. Along the way, his efforts helped to expand the freedom of whites and others to speak, protest, vote, work, exchange, travel, and marry and procreate with African-Americans.

At age 79, Lewis is the last surviving speaker from the March on Washington. He has beaten the actuarial tables for African-American men. But he will not live forever. Last month, Lewis announced he has stage four pancreatic cancer.

On this Martin Luther King Jr. Day, throw a little love to all those in the Civil Rights Movement who gave their minds, gave their bodies, and sacrificed for the cause of freedom. In particular, throw a little love to John Lewis. He could probably use it right now. He most certainly deserves it.