Media Contact: (202) 789‑5200

New Billboards Blame the Onerous Jones Act for Snarling Traffic along Eastern Seaboard

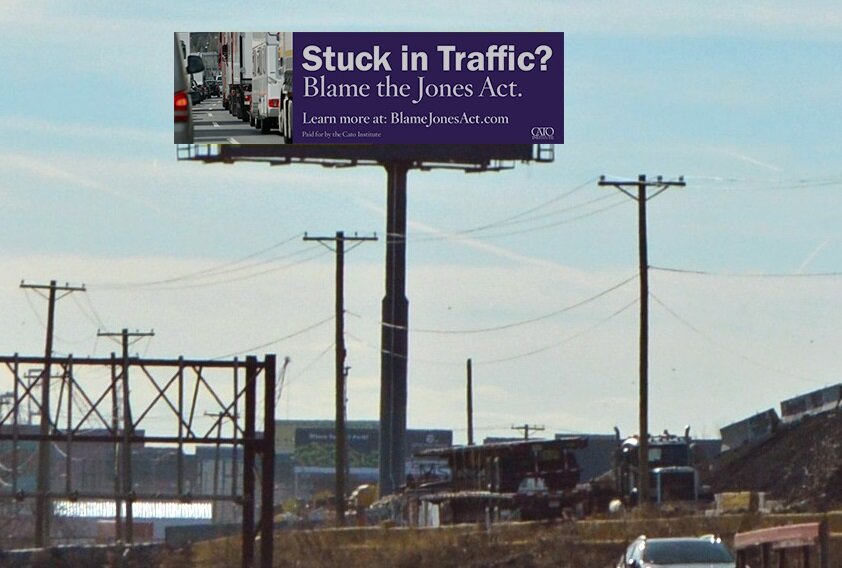

Washington, DC — The Cato Institute is launching a new billboard campaign in the heavily trafficked New York City region this month to educate motorists on the impact of the Jones Act on their daily commute.

The two billboards, located along I-95 at exit 14C (I-78/Newark Airport) in Newark and exit 13 (Conner Street) in the Bronx, beckon drivers with “Stuck in Traffic? Blame the Jones Act.” The boards direct readers to BlameJonesAct.com, which explains that the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, better known as the Jones Act, helps clog America’s highways with 18-wheelers by making it prohibitively expensive for companies to ship goods via container ships, which would be a cheaper and more efficient option were it not for the act.

The Jones Act is a 99-year-old law that restricts shipping between two ports in the United States to vessels that are U.S.-built, U.S.-owned, U.S.-flagged, and U.S.-crewed. Although the law was intended to bolster U.S. shipbuilding capacity and ensure a robust maritime services industry, it has had the opposite effect; in the absence of competition, U.S. shipbuilding has atrophied. About 300 shipyards have closed since 1983, the number of shipyard workers has shrunk from 186,700 in 1981 to 94,000 today, and the number of Jones Act–compliant ships has diminished from 326 in 1982 to 99 today.

As a result, our coastal cities and their populations suffer increasingly costly levels of traffic congestion.

In 2018, Americans lost an average of 97 hours to traffic congestion, costing them nearly $87 billion — an average of $1,348 per driver. The New York metro area in particular experiences egregious traffic jams. Transportation analytics company INRIX lists New York City as one of the top 10 most congested U.S. cities, with drivers spending an estimated 133 hours in traffic per year. However, most heavily trafficked routes, such as I-95, parallel oceans where container transport would be the more efficient passage.

According to new research from Cato’s Herbert A. Stiefel Center for Trade Policy Studies, coastal shipping would be a more cost-effective option for an estimated 25 percent of the trucks operating on surface transportation roads.

“Traffic is increasingly costly to the U.S. economy, and the Jones Act’s restrictions on coastal shipping only make matters worse by incentivizing businesses to move freight on our highways,” said center director Dan Ikenson. “Less than 5 percent of the volume of U.S. domestic freight is transported by water, whereas the comparable figure in Europe is 20 percent. Ending the Jones Act would alleviate the nation’s growing traffic problem and many other problems.”

In addition to swelling traffic, by encouraging more freight to be moved by trucks, the Jones Act results in increased environmental emissions, higher fuel use and costs, and increased prices to consumers.

The billboards are another phase of the Center for Trade Policy Studies’ multifaceted campaign to educate policymakers and the general public on the havoc wrought by the Jones Act. The campaign, in addition to public events and advertising, will publish the work of Cato’s trade experts in four research papers, each tackling a particular aspect of the act. The first, The Jones Act: A Burden America Can No Longer Bear, was released last summer. The next paper will delve deeper into the real costs of the law, expanding on time wasted in traffic congestion, the collateral damage of excessive wear on the country’s infrastructure, and the accumulated health and environmental toll caused by unnecessary carbon emissions and hazardous material spills from trucks and trains.

“Sometimes it’s hard to see all the societal costs associated with bad policy. I’m sure most motorists don’t realize that traffic, pollution, and infrastructure wear and tear are all made worse by the Jones Act,” said Peter Goettler, Cato Institute president and CEO. “We’re trying to spread the word.”