Where do these views come from?

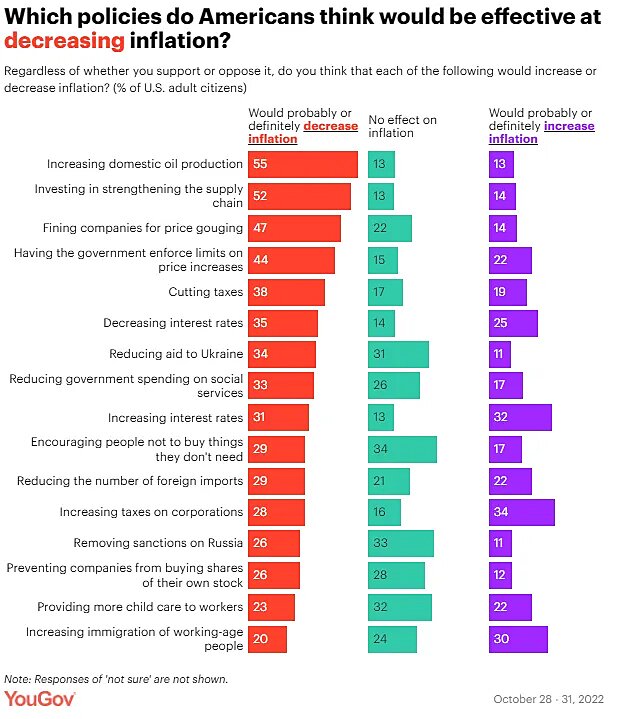

The best explanation for why the median American holds quirky views on inflation is that they see inflation itself as synonymous with certain day-to-day living expenses. So, anything that they think might reduce their major out-of-pocket expenses — lower taxes, lower mortgage rates, less greedy companies, less greedy unions — is deemed good for reducing inflation too.

The question then becomes: where does this misguided understanding of inflation come from?

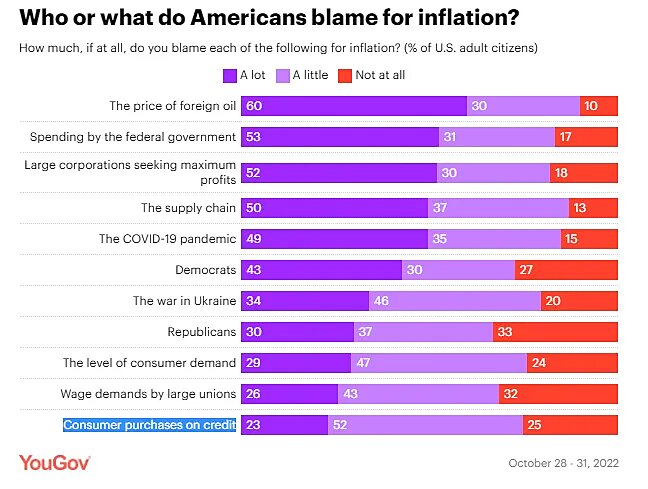

Part of the problem, no doubt, is just a lack of basic economic literacy — not just among the public, but in the broader debates around inflation that the public hear. One reason that I started writing The War on Prices is because I could see that this inflationary moment was leading to all sorts of bad ideas resurfacing, whether theoretical (wage-price spirals) or policy-based responses (price controls). The fact that YouGov didn’t even include the Federal Reserve as a source of blame for inflation speaks volumes. The conflation of inflation with individual price changes is also pervasive.

And, to be honest, the blurring of some of these theoretical distinctions between relative price changes and inflation are not always a bad thing from a policy perspective. Though high inflation periods can lead to mischief with price controls and demagoguery against companies, it can also be a spur to genuinely beneficial deregulation of important industries (see the Jimmy Carter- Ronald Reagan period). If the U.S. removes supply-side constraints against new energy production today, this could have similarly beneficial effects now.

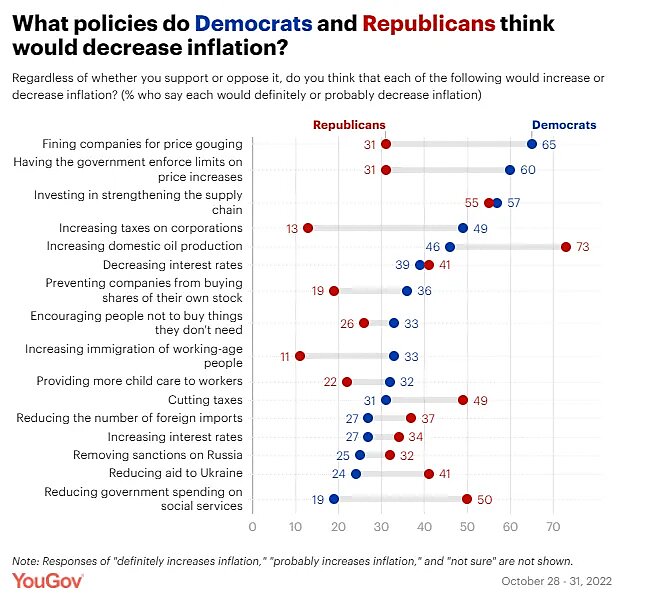

It’s difficult to look at the results by party identification, however, and not conclude that there is also either a top-down absorption of political narratives by party, or perhaps even that respondents tells pollsters what they think a Republican or Democratic loyalist would say.

Democrats are most likely to blame corporations, foreign oil prices, the pandemic, supply-chains, and Republicans for inflation. Republicans are most likely to blame federal spending, Democrats, and foreign oil prices. Both these sets of explanations are obviously convenient electorally for passing the buck when one considers the periods of time in which the parties occupied the U.S. Presidency.

And the blame game feeds through into policy solutions too. Democrats think that price controls, investing in supply chains, and taxing corporations are the most hopeful ideas for reducing inflation. Republicans say it is increasing domestic oil production, cutting taxes, and reducing government spending. Though not all elected politicians from either party would agree with these prescriptions, they do broadly reflect the stated policy positions or complaints from prominent members of the Dems and GOP.