Dear Capitolisters,

With one progressive victory in the bag, the Biden administration and congressional Democrats are now—as promised—itching for more. Over the last few days, details have emerged about the White House’s “infrastructure” (scare quotes intentional) bill and how Democrats plan to pay for some of it. As helpfully tabulated by economist Donald Schneider, the entire package includes about $3.75 trillion in new spending and $2.67 trillion in new taxes, thus generating another $1.1 trillion in new debt. These details, of course, are subject to change, but one part of the package seems very likely to stick: increasing the corporate tax rate to 28 percent from 21 percent—i.e., where the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) put it in 2017—and making a few other moves to increase taxes on multinational corporations and shareholders. It’s thus a perfect time to dig into the literature on corporate taxes and their economic effects—literature showing that, while “taxing corporations” might make for good politics and great soundbites, it’s pretty bad tax policy.

Where We Are

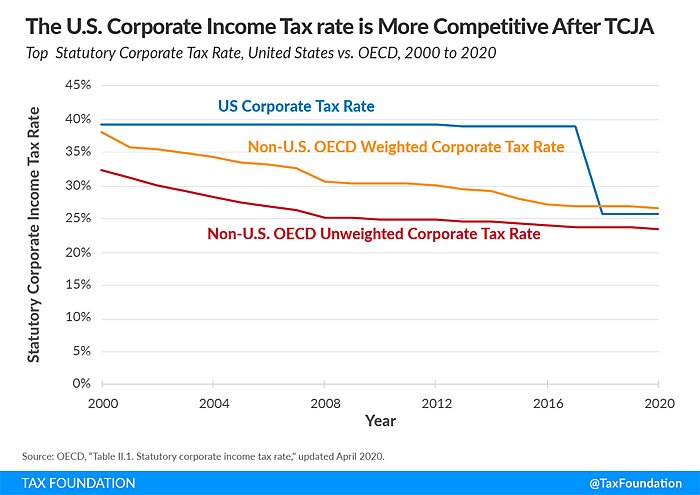

Prior to the passage of the TCJA, the United States had a combined federal-state corporate tax rate of 38.9 percent, almost all of which (35 percentage points) was at the federal level. Because many countries—including more “progressive” ones like Canada and Sweden—lowered their corporate tax rates over the last 40 years, the United States in the 2010s ended up with one of the highest statutory corporate tax rates in the developed world (and the highest in the OECD). Following the TCJA, which lowered the federal rate to 21 percent, corporate tax rates in the United States were more in line with the OECD average but certainly not “low” by any reasonable definition:

The TCJA also ended up lowering the effective corporate tax rate in the United States (meaning the average amount that corporations actually pay in income taxes), though this stat obviously varies a lot by company and calculation method. Regardless, the general trend is clear: Pre-TCJA, U.S. corporations faced an average effective tax rate that was higher than most peer countries; post-TCJA, it was better but still not world-beating. For example, the OECD calculates rates of 37.5 percent and 17.4 percent for respective average and marginal effective U.S. corporate taxes in 2017 and 24.6 percent and 11.2 percent rates, respectively, in 2019—basically in the middle of the OECD pack. Similar analyses have been completed here for just multinational corporations and here for just the United States.

Even with lower rates, however, corporate taxes in the United States remain uncompetitive in several respects. First, the combined U.S. statutory rate is still higher than 24 of the 36 developed economies examined by the OECD, as well as the average rate in the OECD (23 percent) and Europe (21 percent) and the rates in a lot of “competitor countries” like Switzerland (15 percent), the U.K. (19 percent), and South Korea (25 percent). Similar trends apply to the effective corporate tax rates discussed earlier—we’re fine overall but still worse than many similarly situated countries vying for the same pot of multinational investment dollars.

The World Bank’s latest Doing Business report provides additional details on the tax burdens that American corporations actually face and how these stack up against corporations in other countries. The report finds that the United States in 2020 ranked 25th in the world in “paying taxes,” which includes both the total tax rate that a “normal” corporation pays across all relevant jurisdictions and the various administrative burdens that it faces. On just the tax rate part of that score—which includes federal, state and local taxes—the United States’ 36.6 percent combined rate is slightly better than the OECD average (39.9 percent) but still higher than almost 100 other countries, including Singapore (21 percent), Denmark (23.8 percent), Canada (24.5 percent), the U.K. (30.7 percent), New Zealand (34.6 percent) and Norway (36.2 percent).

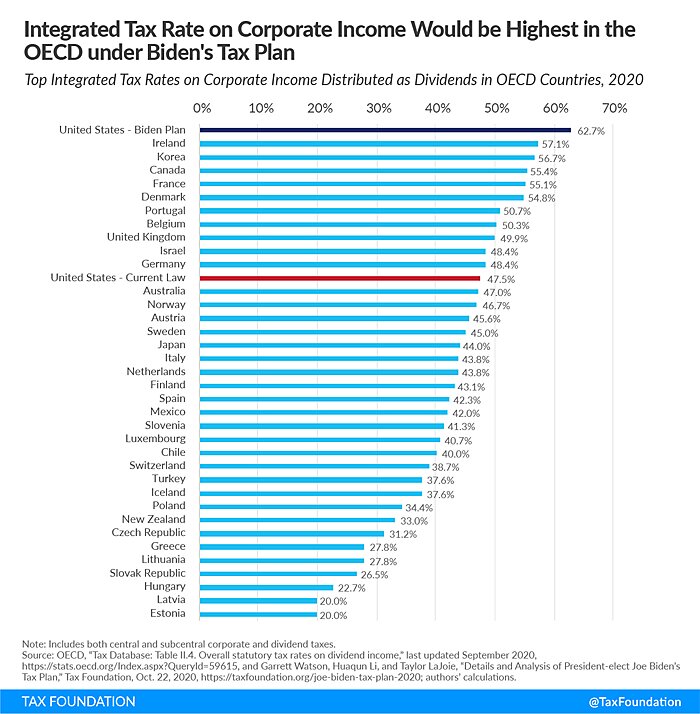

Second, the statutory rankings we read about in the press do not include U.S. taxes on dividends and capital gains, which are paid by shareholders and amount to a second layer of corporate income taxation (backgrounder here). According to Tax Foundation calculations, when this second tax is included, the top U.S. “integrated tax rate on corporate income” stands at about 47.7 percent, again ranking in the bottom third of OECD countries:

In short, the TCJA improved the United States’ corporate tax competitiveness, but most certainly didn’t turn the United States into some sort of “tax haven.” And there remain plenty of places in the world that have less burdensome statutory and effective corporate tax systems than the United States. Whether you like it or not, tax burdens are one of many factors that corporations consider when deciding where and how much to invest in things like facilities and equipment, and that this capital is highly mobile. Higher-tax countries can overcome that burden with other policies and better people, but there’s little doubt that, in the race for global capital, these places are starting from the back of the pack.

The Perils of Corporate Income Taxes

There’s also plenty of evidence that corporate taxes are a pretty lousy way to finance government operations and raise all sorts of problems. Most basically, there’s the fact that corporations, while technically paying corporate taxes, don’t bear their ultimate burden (what we call “tax incidence”). Instead, academic research shows that corporate taxes are actually paid by a combination of shareholders, workers, and consumers. A 2020 paper, for example, estimated that “the incidence on consumers, workers, and shareholders is 31 percent, 38 percent, and 31 percent, respectively”—thus showing that corporate taxes aren’t very good at taxing “capital,” and that a substantial share of corporate taxes are simply passed on through retail prices or lower wages. As AEI’s Michael Strain recently noted, even left-leaning economists acknowledge that workers bear a significant portion of a corporate tax burden.

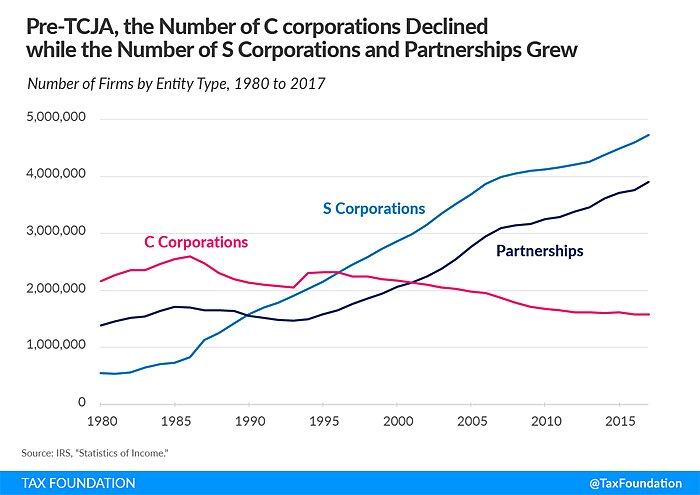

Onerous corporate taxes also encourage all sorts of clever accounting to avoid them—great news for accountants and tax lawyers but not so great for the rest of us. For example, the Tax Foundation notes that the pre-TJCA system encouraged companies (1) to shift profits abroad and in some cases even move their corporate headquarters overseas to avoid U.S. tax liability (aka “inversions”—some real-world examples here); and (2) to reorganize into “pass-through entities, which are subject to only one layer of tax at the individual level” but still protected from some legal liability, instead of classic “C corporations”:

This trend likely helps to explain why corporate tax revenues have historically been relatively low compared with other revenue sources (e.g., income taxes) in the United States: Pretty much nobody wanted to be a corporation if they could possibly avoid it. The TCJA may be changing that dynamic: Economists at Penn’s Wharton School of Business have estimated, for example, that the TCJA could cause more companies to switch back to traditional “C corporations.”

New academic research not only confirms the pre-TCJA trend toward noncorporate business formation in the United States, but also shows that this tax-induced decision can have distortive economic effects on investment, firm growth, and even inequality:

Higher levels of corporate taxation change the composition of economic activity both by encouraging entrepreneurs to establish their firms as unincorporated businesses and—more importantly—by reducing the size and growth of corporations, thereby causing noncorporate businesses to expand. This reallocation of economic activity represents substitution away from relatively safer economic forms and styles of business organization into those that offer high returns to some and low returns to others.

As a consequence, there will be greater numbers of entrepreneurs who are highly successful and join the ranks of the rich, just as there will be greater numbers of unsuccessful businesspeople. The result is to make the distribution of income less equal…

Other economic harms arising from high corporate tax rates in the United States and elsewhere include:

-

Lower investment and economic growth, thus reducing wages and living standards over time: “the economic literature shows that corporate income taxes are one of the most harmful tax types for economic growth, as capital investment is sensitive to corporate taxation.” (Translation: companies invest less in places with high corporate tax burdens.) As we discussed a few weeks ago, economic growth isn’t the only thing that matters in an economy, but it’s still quite important.

-

Less innovation. Recent studies of the United States and China show a strong connection between corporate tax rates and firm innovation (e.g., spending on R&D, hiring high-skill workers, filing patents, and introducing new products). In short, higher corporate taxes mean less innovation, while lower ones mean more.

High corporate tax burdens have also been tied to lower productivity and distorted corporate decision-making. It’s thus no wonder that countries around the world have been lowering their corporate tax rates for the last 40 years.

Biden’s team, apparently, doesn’t care about this research and will seek to increase U.S. corporate tax rates substantially. In fact, its plan to increase the corporate tax rate to 28 percent and tax capital gains and qualified dividends at the ordinary income tax rate of 39.6 percent would put the United States back in last place among OECD nations with a top integrated tax rate of almost 63 percent (and just the 7 percentage point corporate tax rate increase alone would put us at 54.5 percent):

The Tax Foundation adds that “[i]f the Biden tax plan were fully implemented, the U.S. rank on the Tax Foundation’s International Tax Competitiveness Index would fall from 21st in 2020 to 30th, with the corporate rank falling from 19th to 33rd overall.” It’s hard to see how this could possibly be good for attracting new companies, entrepreneurs, and investment in the United States.

But What About …

Okay fine, corporate tax fans say, that’s the basic economic theory, but it’s not reality. In particular, these folks commonly allege that we need higher corporate taxes because certain large companies—Amazon, for example—pay “no taxes” or because the TCJA simply didn’t boost business investment as intended. Neither case, however, withstands serious scrutiny.

On the common claim that corporate taxes need to be higher to force Amazon and other big companies—especially tech companies—to pay their “fair share,” there are a few problems. First, as already noted, large corporations don’t actually pay these taxes and shareholders pay only a portion of them. Many companies, moreover, can often avoid U.S. corporate taxes by moving offshore or maintaining a noncorporate form. Second, in almost all of these cases, the companies aren’t doing anything illegal.

Third, and relatedly, this criticism ignores why Amazon and many other U.S. corporations that allegedly pay low or “no” taxes actually have tax bills like that: because they’re doing precisely what Congress told them to do. The Wall Street Journal’s Richard Rubin walked through Amazon’s case back in 2019, looking at its public tax records from 2018 (TCJA) and prior years (pre-TCJA, obviously). He finds that not only did Amazon pay $1.2 billion in 2018 taxes—up from only few hundred million in 2015–16—but the reasons for its still-relatively low effective tax rate (ranging from 8 to 13 percent since 2002) were neither nefarious nor an indictment of current law. In particular, Amazon lowered its taxable income in three main ways: (1) applying previous period losses (“carryforwards”), which let all companies “smooth tax payments across business cycles and a company’s lifespan”; (2) tax credits mainly related to R&D; and (3) deducting (“expensing”) business investments (e.g., cloud computing or solar farms), on which Amazon spent more than $160 billion since 2011. Many other large companies — as even their left-leaning critics acknowledge—have employed similar (lawful) strategies to lower their tax liability.

One can argue that some of these tax rules should be changed—for example, the R&D tax credit has been found to suffer from design and implementation problems—but that doesn’t refute the aforementioned data and research on U.S. corporate tax rates generally, nor is it an indictment of the now-lower U.S. corporate tax rate. As Rubin put it, “the current corporate tax system was designed by Congress to encourage investment and research and let companies realize the benefit of early losses when they become profitable.” Amazon and many other companies utilize those rules as Congress intended, and Biden’s team doesn’t appear to be targeting them. Indeed, they might actually expand corporate tax incentives—precisely the wrong approach if one worries about corporations taking advantage of corporate tax “loopholes,” especially when combined with a higher statutory rate that would encourage companies to use them.

Second, we hear today that the TCJA failed because U.S. corporations simply bought their own stock (“buybacks”) instead of plowing that money back into the economy (for example through investment or pay raises). However, as Cliff Asness explained in 2018 (or Tyler Cowen or John Cochrane or Ryan Bourne, all around the same time), the “buyback” hysteria reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of corporate finance/governance and basic macroeconomics. In short, an initial round of share repurchases was the predictable result of a bunch of corporations having unplanned “excess capital” on their hands when the law took effect—choosing to distribute that money to shareholders instead of plowing it back into the company. However, those shareholders can (and almost certainly will) reinvest any cash windfalls into other, likely more productive U.S. endeavors; the “buyback companies” can (and actually do) use debt (e.g., corporate bonds or loans) to raise new capital for wages or investments; and there is little long-term connection between share repurchasing and corporate investment levels (see also, this Federal Reserve research helpfully summarized by Schneider). As these guys note, economic theory says that, over the longer term, total business investment will rise, regardless of any share buybacks.

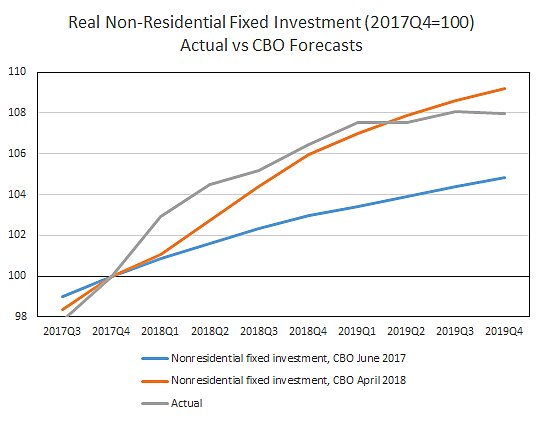

Unfortunately, the pandemic intruded on the TCJA’s corporate tax/business investment experiment, but the initial returns (pun intended!) weren’t nearly as bad as some critics have claimed—even the ones who didn’t make rudimentary analytical mistakes. As Schneider noted last year, for example, U.S. business investment in 2018 and 2019 easily beat the CBO’s pre-TCJA forecast and “ended up matching what CBO said would occur even in the face of a trade war and rate hikes”:

A new report from the Joint Committee on Taxation, using actual corporate tax returns for 2018, also found that “business investments in things like plants and equipment, as well as employment in the U.S., increased following enactment of the law.” And research from the St. Louis Federal Reserve has shows that “both innovation and [venture capital] investment increased significantly” after the TCJA, thus laying the groundwork for faster economic growth in the future:

Schneider’s second point above is also essential to any discussion of the TCJA and business investment: As we’ve discussed here (repeatedly!), numerous studies show that Trump’s trade wars had a real and significant impact on domestic business investment as tariffs ate into corporate profits and uncertainty gripped global markets. The Fed’s tightening also may have played a role—something the Fed itself sorta admitted in late 2019. It’s thus unsurprising that Schneider’s gray line, which was cruising above-forecast right before and after the TCJA was enacted, started petering out in 2018–2019 as the rate hikes and trade wars kicked in. People will call that a failure of the TCJA’s corporate tax provisions, but they really, really shouldn’t.

“what tax cuts gave by way of optimistic forecasts, Trump’s trade war has taken away. Persistent uncertainty has led companies to cut back on investment spending, while confidence has faltered.” https://t.co/kGSueHDsZB pic.twitter.com/rrAKeIrXDU

— Scott Lincicome (@scottlincicome) October 2, 2019

(And you pro-tariff TCJA-lovers out there can’t say you weren’t warned.)

Summing It All Up

The TCJA was far from perfect, but its basic corporate tax reforms moved the United States in the right direction—from one of the highest corporate tax jurisdictions in the world to one that is today at least competitive with most of the developed world, in terms of both the basic tax rates on paper and the actual tax burdens imposed on U.S. corporations. These reforms are consistent with oodles of research showing how high corporate tax rates discourage investment, economic growth, and innovation, while likely burdening U.S. workers and consumers more than those fat-cat capitalists we all (apparently) love to hate. Biden’s corporate tax plans, assuming they make it into whatever final package Congress will consider, would undo these recent improvements, raising rates and adding complexity and uncertainty at a precarious moment for the U.S. economy.

Indeed, by reportedly considering whether to phase-in a corporate tax rate increase, the Biden administration seems to understand the economic risks that the policy entails. As AEI’s Kyle Pomerlau notes, however, that ploy won’t be effective, and “[t]he simplest way to avoid the economic harm of raising the corporate tax rate is to not raise the rate.”

Unfortunately, the Biden administration doesn’t seem to be listening.

Chart of the Week

Construction materials costs have skyrocketed; guess what’s not helping:

The Links

Inu Manak and I assess new legislation to reform Section 232

The American Rescue Plan and macro risks (Larry Summers agrees)

Chinese industrial policy isn’t going great (more)

Britain’s “one-jab” strategy is working

Cruise companies are offering land-based trips through Alaska (thanks to U.S. cabotage laws)

The eviction moratorium keeps losing in federal court

New research on immigrants’ benefits for Americans (and another)

U.S. sends millions of vaccine doses to Canada and Mexico

Re-joining the TPP (CPTPP) is a no-brainer

Is Ford shifting vehicle production to Mexico?

Pharmaceutical manufacturing expansion in North Carolina

Federal flood insurance is horrible policy