Dear Capitolisters,

There’s a frequent excuse for all sorts of government interventions in the market: While they may be costly, risky, and counter to standard economic theory, they are nevertheless essential to counter a foreign authoritarian threat—one that, so the theory goes, suffers none of the failings of our decadent liberal democracy. Dictators and central planners, we’re told, can “play the long game” (or “plan for the long view”), ignore (or crush) domestic opposition, quickly implement decisive economic or military action, and willingly absorb any resulting side effects or casualties. Thus, it’s imperative that the United States urgently pass and implement policy X, even though it might not make much economic sense.

Having grown up during the Cold War, lived through the Japan hysteria of the 1980s and 1990s, and long been a fan of free markets and liberal democracy (for all their warts), I’ve long been baffled by this theory, which has nevertheless proven popular with the last two presidential administrations and scores of wonks and pundits. Yet recent events show why we still should be skeptical of supposedly omniscient authoritarian regimes and of those once again claiming we must abandon Western capitalism to save it.

Authoritarians Reeling

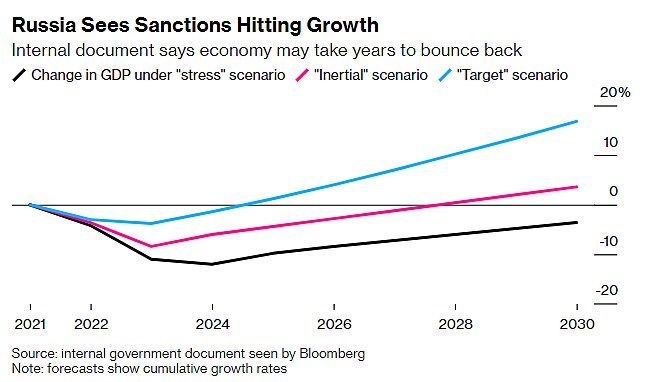

Most obviously, there’s Russia, which has in the last few weeks seen multiple battlefield defeats in Ukraine, a disastrous public mobilization effort, and now the important (and “humiliating”) destruction of a strategic bridge to/from Crimea—once a symbol of Russian might. The war in Ukraine has also left an indelible mark on the Russian economy, following broad international sanctions and the wide-scale departure of multinational investors. As Bloomberg reported in early September, in fact, an internal Russian government report estimates that “Russia may face a longer and deeper recession as the impact of US and European sanctions spreads, handicapping sectors that the country has relied on for years to power its economy. … Two of the three scenarios in the report show the contraction accelerating next year, with the economy returning to the prewar level only at the end of the decade or later”:

The country is also experiencing “brain drain,” as educated and wealthy Russians flee for better, safer countries. And the elites who have stuck around are starting to grumble: “President Vladimir Putin is grappling with the gravest domestic crisis of his 23-year rule: an increasingly public quarrel inside the Russian elite over who is to blame.” Now, the U.S. Defense Department has started openly positing that Russia’s problems in Ukraine are a cautionary tale for China and its ambitions in Taiwan.

Speaking of …

The numerous problems in China that we discussed in June have further deteriorated in advance of this week’s Communist Party Congress and the reappointment of President Xi Jinping for another (this time, lifetime) term. The nation’s biggest immediate problem continues to be a rigid and irrational “Zero COVID” policy that’s wrecked China’s economy, eroded elite public support for the government, and will nevertheless continue into 2023, not because it’s good policy but because ending it around the time of the big party confab would make Xi, the CCP, and the country’s health care system look bad:

Some analysts have predicted that the zero-Covid policy could be dropped after the party congress. But the coronavirus strategy is increasingly seen as a test of the party’s legitimacy and too closely attached to Xi, the country’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong.

“Shifting away from the zero-Covid policy right after the party congress will look like he is not totally in charge, like he was forced to back away from one of his signature policies right after a leadership transition,” said Xinran Andy Chen, a senior analyst at China consultancy Trivium, based in Shanghai. “Letting it go will be a very gradual process.”

Underlining Xi’s stubborn adherence to zero-Covid are fears over China’s healthcare system, which in many parts of the country is unprepared to deal with sudden or mass patient influxes.

Part of the problem is that China continues to refuse to buy and deploy Western mRNA vaccines because Moderna and BioNTech/Pfizer won’t hand over their intellectual property and China’s home-grown versions are still not ready for primetime. Thus, as one expert put it, it’ll take “some miracles” for Xi and the CCP to abandon Zero COVID, even as it destabilizes the nation.

China’s policy-driven property problems have also deteriorated, as developer-specific issues have morphed into a “slow-motion financial crisis” because massive “local government financing vehicles,” which have “fueled China’s investment-driven growth” for the last decade or so, are short of funds or facing default:

The upshot is that — absent a big bailout from Beijing — local governments will struggle to honour the debts of at least some of the thousands of LGFVs that they own. If defaults do occur, analysts say, they risk destabilising the whole stack of LGFV debt, which stood at about Rmb54tn (US$7.8tn) at the end of 2021

Yes, that’s $7.8 trillion, with a T.

Other problems, beyond the long-term demographic issues and others we’ve already discussed, have also emerged. For example, after spending about $1 trillion on loans to numerous developing countries, China’s once-vaunted Belt and Road initiative (which many U.S. wonks wanted to copy) is now hemorrhaging cash, laden with bad debts, and getting rebranded as “Belt and Road 2.0.” Zero COVID and Xi’s crackdown on tech and other private companies, meanwhile, have caused entrepreneurs to flee the country. And they’re fleeing Hong Kong, too. Now come the inevitable purges of various party apparatchiks for their totally-not-sketchy “crimes” of “disloyalty” and “graft.”

Finally, there’s Iran, where massive protests have erupted in response to the brutal detention and likely murder of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman who was picked up by Iran’s “morality police” for violating the Islamic country’s strict dress code, and the government’s subsequent crackdown on dissent. Protesters have emerged in traditionally conservative neighborhoods, are getting more aggressive, and hacked a state broadcast over the weekend. Even the police may be joining in. Iran has obviously survived many past protests, but experts are speculating that these protests—which, despite a brutal crackdown have entered their fourth week and are expanding (even into Iran’s energy sector)—could be different this time:

What makes today’s uprising a revolution is twofold: the public’s almost universal willingness to openly confront and fight the security forces in the streets, and the slogans that leave no room for misinterpretation of the protesters’ core demand: “Death to the Dictator” and “Death to the Islamic Republic.” No one is talking about votes and elections anymore.

According to one Iran historian earlier this week, “cracks in the regime are starting to show.”

(I’m pretty sure he’s talking about only Iran, but the shoe fits other authoritarian feet too.)

Explaining Authoritarian Failures

Surely these problems, while serious, don’t necessarily mean that Putin’s Russia, Xi’s China, or Khamenei’s Iran will collapse anytime soon. Yet the recent and widely held view of these illiberal regimes as unstoppable (or immovable) threats to a “soft” Western world has taken an undeniable hit—one I’m pleased to see finally gaining attention outside of these virtual pages. Historian Niall Ferguson has even gone so far as to recently predict that, based on recent events, all three regimes will fall in his lifetime. Others aren’t that bold, but even cheerleaders are on defense.

The authoritarian threat has once again given way to the authoritarian reality.

All of this raises the obvious question of why authoritarians don’t actually make great supervillains. Much of it, I think, comes down to the inherent nature of the regimes themselves. In their 2012 book Why Nations Fail, economists Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson argue that rich countries are rich because they have “inclusive economic and political institutions” (that is, they “create the incentives and opportunities necessary to harness the energy, creativity and entrepreneurship in society”). Poor countries, by contrast, are poor because they have “extractive economic and political institutions,” which allow elites to take power and wealth by force. Others, such as Nobel laureate Douglass North and political scientist Barry Weingast, have argued much the same.

As my Cato colleague Marian Tupy and co-author Gale Pooley summarized in their book Superabundance (which I reviewed here), institutional makeup affects much more than just GDP:

Inclusive economic institutions rely on the existence of political institutions characterized by power-sharing and wide distribution of decision making among the elites, businesses, civil society, and, ultimately, individuals. The elite are, in a word, constrained. Unconstrained decision making, in contrast, centralizes power in the hands of a small elite or, in extreme cases, in one individual. The former fosters competition, coalition building, and accountability. The latter fosters elite predation.

Centralized power by an unelected elite—governments of men, not of laws—might make the high-speed trains run on time, but it also carries a massive risk of stubborn, foolish resistance to change in order to protect elite legitimacy, even in the face of mounting evidence that such change is needed. Foreign policy analyst Richard Hanania—certainly not some pollyannaish supporter of Western liberalism—put this well a couple weeks ago:

If you look at Chinese and Russian failures in 2022, they appear on the surface to be very different. Russia was too risk-acceptant, and intoxicated with masculine dreams of conquest. China has been too risk-averse, and shown itself to be too neurotic to be able to respond to threats in a measured way. But at a deeper level, both involve a governing elite that is willing and able to drag a public towards making massive sacrifices for a fundamentally irrational goal.

As he notes, it’s not impossible for a dictatorial regime to produce long-term economic growth and social stability, but authoritarian institutions all but ensure that this is the very (very) rare exception to the general rule of poverty, instability, and eventual collapse.

Liberal democracies, by contrast, tend to be not only richer than authoritarian regimes but also more dynamic—i.e., they’re able to change quickly based on new information that only an open society provides (whether the elites like it or not!). As The Dispatch’s own David French noted last week, this helps to explain why, as numerous studies show, democracies tend to win wars against autocracies:

The combination of democratic accountability, economic vitality, and the individual liberty protected by free societies yields armies that reflect their nations—more technically advanced, more creative, and with command structures that reward success and punish failure.

…

The economic freedom that yields prosperity is accompanied by political freedom that births a deceptive form of contention. Although it is very true that polarization can be dangerous and that political combat can grow far too toxic, the baseline level of relentless self-critique is also a source of strength. Our liberal democracies are thus learning organisms. We know how to change.

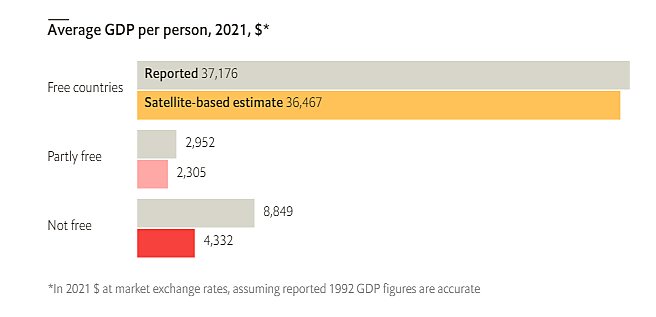

The quantity and quality of information underlying elite decision-making matters a lot here, with authoritarian regimes again holding the short end of the stick. Take, for example, the great new study behind last week’s Chart of the Week, which compared nations’ reported GDP figures with a proxy estimate based on satellite images of electricity usage. The result, per The Economist: “dictators’ reported GDP tended to grow much faster than satellite images of their countries would suggest,” while democracies’ figures basically matched. In fact, “as countries moved towards or away from dictatorship, their numbers grew more or less suspicious.”

As The Economist notes, the origin of this informational asymmetry very likely boils down to the nature of the governments themselves:

Part of what makes dictatorships dictatorships is that questioning the official line is dangerous. At the same time, autocratic regimes have a strong incentive to report healthy growth: its absence may be taken as a sign of incompetence or weakness, which dictators can ill afford.

Authoritarian institutions thus encourage misinformation from both the bottom up (e.g., local governments or generals) and the top down (e.g., the central government or leader), and they provide government officials with the mechanisms to forcibly restrict countervailing data. This informational vacuum might help a dictator look good (for a while, at least), but it’s obviously problematic for government and private sector decision-making on economic, military, public health, and other crucial policy matters. Open economies, by contrast, rarely suffer from such an affliction: Even where the state tries to distort or withhold information, private actors (media, academia, think tanks, for-profit research organizations, etc.) will eventually fill the void. And democratic accountability will probably (again, eventually) make elite leadership pay for any grievous errors.

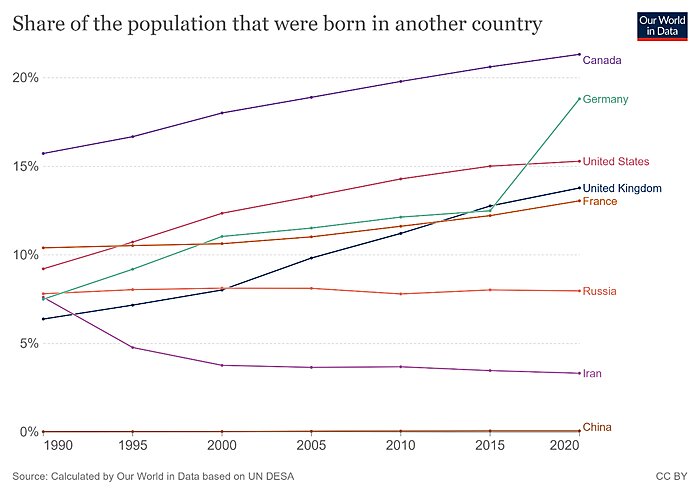

Other factors, such as liberal democracies’ relative openness to trade, immigration (see chart below), and diplomatic engagement, are also surely at play. All that isolationist “fortress” talk might sound tough, but it usually portends lower long-term economic growth, less innovation, demographic problems, and—contra the conventional wisdom—a decided lack of resiliency when shocks inevitably hit (see, e.g., baby formula).

Engagement and interconnectedness can also come in handy when things go sideways, in both offensive ways (e.g., the international response to the Russian invasion) and defensive ones (e.g., U.S. exports of liquefied natural gas to Europe or U.S. imports of European baby formula). It pays to have friends around the world, and that usually requires being, you know, friendly to others.

Summing It All Up

None of this means that Western nations can just take the rest of the day off, or that authoritarian regimes pose no threat to the United States and other countries around the world—in the short term, at least, weakness might make them more dangerous. In the long term, however, distant history and recent events give us strong reasons to doubt that illiberal strongmen are such a dire threat to the United States as to necessitate abandoning our open, liberal system and embracing illiberalism and central planning ourselves. Time and time and time again, authoritarian regimes’ serious institutional shortcomings make serious problems all but inevitable. And they render the common view of the omniscient authoritarian chessmaster, used to sell so much bad U.S. policy, beyond farfetched.

We liberals have problems too, of course, but our flaws are, importantly, out in the open. Authoritarians’ much bigger flaws are usually hidden.

Until they aren’t.