One gripe that free-marketeers have long had with antitrust or competition laws is that they are necessarily static in nature. By that, I mean they seek to identify the contours of current markets and to stamp out anticompetitive conduct that is breeding inefficiency today by firms deemed to have monopoly power.

This approach is understandable. Policymakers can’t and shouldn’t second-guess the future of an entrepreneurial market economy that’s constantly evolving. But this static focus inevitably means ignoring and underestimating an important margin of competition over time. Namely: “creative destruction.”

Joseph Schumpeter described this form of competition as “the new commodity, the new type of organization – competition which commands a decisive cost or quality advantage and which strikes not at the margins of the profits and the outputs of the existing firms but at their foundations and their very lives.”

As an (extremely under-appreciated) 2019 paper of mine documented in extensive detail, U.S. antitrust history is littered with examples of regulators shining the spotlight or investigating companies just as the tide was turning on their dominance in their core market.

U.S. antitrust authorities were long concerned about Kodak’s sustained superiority in the consumer film camera markets. Then digital cameras came along and revolutionized the industry. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) spent two years between 1976 and 1978 investigating whether IBM had monopolized the “office typewriter industry.” This was just as personal computers were just about to take off. Of course, Microsoft was dragged through the courts for years for the supposed anticompetitive consequences of tying Internet Explorer into Windows. That browser “monopoly” was then ultimately usurped by Mozilla Firefox and Google Chrome.

Today, the FTC and Congress have their eyes set firmly on various “Big Tech” companies — specifically Meta, Google, Amazon and Apple. The neo-trustbusters in Washington regularly throw the term “monopoly” around to describe them. And yet, a ton of evidence of late reminds us that, not only do these companies face meaningful ongoing competitive pressures that belie the idea that they are entrenched monopolies, but some face very real threats of cannibalization from those creatively destructive forces Schumpeter highlighted.

Meta

Certainly, Meta (formerly Facebook) is having a particularly rough time right now. The tech giant has drawn scrutiny from lawmakers and regulators around the world. The FTC is attempting to block Meta’s acquisition of virtual reality fitness app producer Within and, just last month, the UK’s Central Markets Authority successfully forced the company to divest from Giphy. Both regulators claimed that Meta was abusing its monopoly power to drive out competition and solidify its dominance by purchasing nascent competitors.

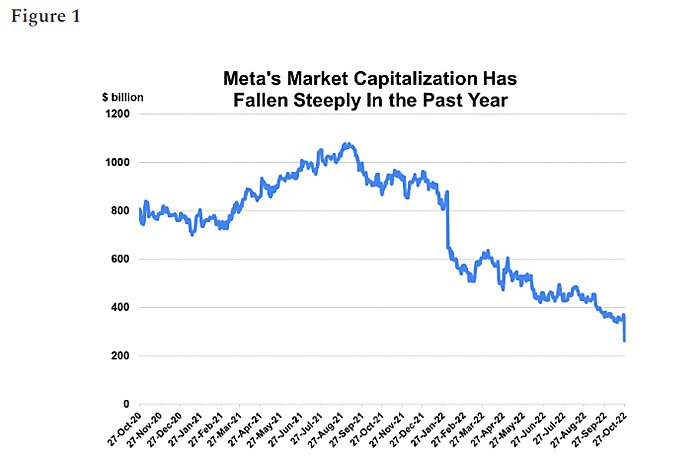

Investors, though, have far less confidence in the firm’s “monopoly power.” Meta’s market capitalization has fallen from almost $900 billion in October 2021 to a low of $263 billion at the end of October. As I wrote last week, it has lost over 70 percent of its value in just 12 months (see Figure 1).

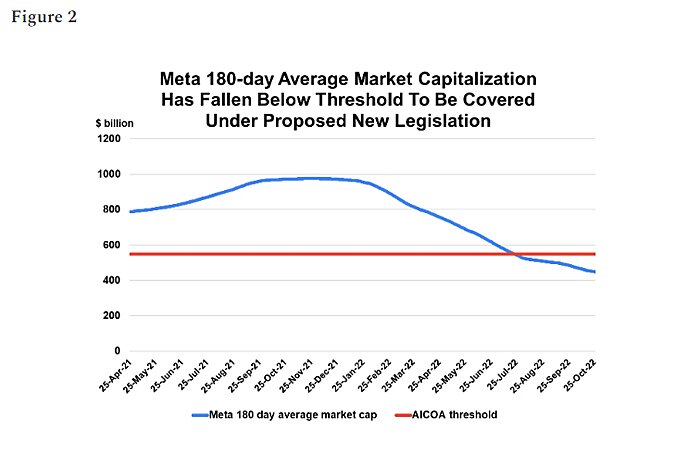

So steep has been the stock price decline that the company’s market value now lies below the $550 billion threshold that proposed U.S. legislation uses as a condition to determine whether digital platforms should be covered by new laws imposing restraints on their conduct (see Figure 2). At what point does the company cease to be “Big Tech”?

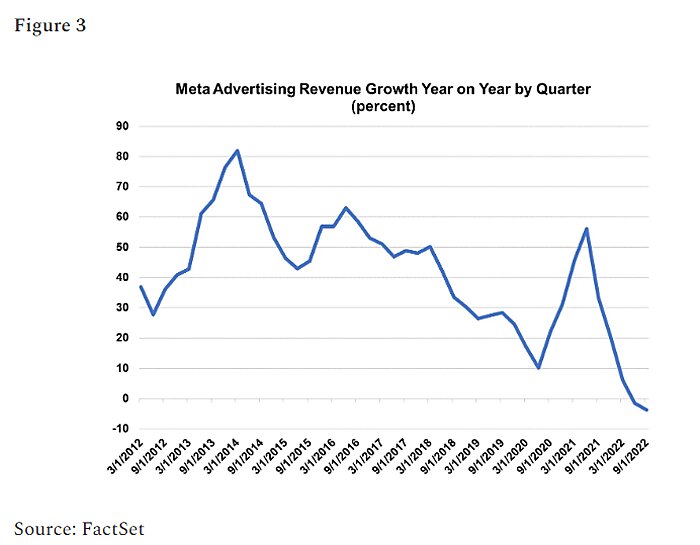

Meta’s traditional core revenue source, digital advertising, recently shrank for the company for the first time since 2012, and there seems to be little sign of that abating.

How much of this will turn out to be a function of the broader economic downturn affecting digital advertising spend, as opposed to a Meta-specific issue, will become clearer in time. What we do know is that Facebook (as Meta’s original product) produced value for advertisers in part by keeping users on the platform for long periods of time. For all that legislators have tried to gerrymander the definition of Facebook’s market to make out it is a monopoly in social media, it is evidently at severe risk in this regard from rapidly growing platforms such as TikTok.

Not only does TikTok have an estimated 80 million U.S. monthly users (and growing), but the average viewer watches videos for a massive 80 minutes a day – more than the time spent on Facebook and Instagram combined.

Meta is visibly worried about the TikTok threat — how else to explain them opting to replicate the sort of product TikTok offers through its own Reels videos? Likewise, although many Americans still use Facebook for news consumption, the number who report doing so is steadily declining, as TikTok’s is accelerating (see Figure 4). Globally, TikTok has now just under half the ad reach of Facebook, but is growing at a rapid clip as the latter declines.

To clarify: Facebook is by far the world’s most used social media platform, at least for now. And just looking at Facebook anyway is to ignore that parent company Meta is making big, risky investments in its metaverse products (which in the past 9 months, have lost the company $9.4 billion).

Perhaps the pivot to these endeavors will one day pay off, or maybe it won’t. The point is that along its traditional social media domain, Meta is facing fierce competition right now. That the company is still a big company is irrelevant for determining whether it is a “monopoly.” Vice recently declared: “Facebook’s Monopoly Is Imploding Before Our Eyes,” with a subheading citing competition as one reason for its downturn. The irony was apparently lost on the sub-editor.

Alphabet/Google

In part as a result of this user market competition, both Meta and Alphabet (Google) are also facing meaningful new competition in the digital advertising sphere, which is obviously the revenue generator of their historically core products. Indeed, Google and Meta were described as a “duopoly” in online digital advertising for years. But as Figure 5 shows, their combined share of total digital advertising spending has been falling and is expected to fall even further in the near future.

In the technology sector, innovation plays a large role in a company’s ability to remain successful. Another “Big Tech” company, Amazon, has innovated to compete vigorously on the digital advertising front by focusing on getting brands to pay for product promotion on the Amazon website and app.

This year, it introduced an array of services that put a twist on traditional advertising models, including allowing brands to offer Amazon credit to shoppers who purchase the featured product. The e‑commerce retailer is now expected to capture 13 percent of worldwide digital advertising revenue by 2026. For scale, eMarketer reports that Amazon made more money from advertising in Q2 than it did from Prime membership fees.

Amazon is not the only company innovating where adverts are concerned. TikTok, mentioned above, is seeing rapidly rising ad revenue and is expected to overtake Alphabet’s YouTube by revenue by 2025. It is developing generous revenue-sharing arrangements with content creators to generate a virtuous circle of user engagement driving higher advertising reach.

Other companies are identifying new ways to compete in the digital ad space too. Apple has recently expanded digital adverts on its app store. Uber is set to sell ad space inside its ride-hailing and Uber Eats apps, as well as develop in-vehicle digital ads. Instacart is developing more specialized video ad packages and advice for brands. Snapchat, Spotify, Yelp, Roku, Walmart, IAC, Pluto TV, and Tubi are all set to join them in becoming $1 billion ad platforms in the coming years. Finally, in the broader ad market, platforms such as Netflix are set to introduce ads too.

As we can see, the advertising industry is ever-evolving, with competition across many different domains and plenty of websites continuously rethinking the best balance between digital advertising and subscription services. No wonder the FTC, committed to ensnaring its Big Tech bête noires, has previously insisted on distinguishing “social advertising” from “display advertising,” “search advertising,” or “offline advertising” to make the companies look more dominant.

Google, of course, as a company, has long since diversified into many other domains than the search and digital ads model, including cloud services, self-driving cars, smart home appliances and life sciences. Its traditional general search engine business is still dominant — although its market share worldwide in desktop general search has fallen from just over 90 percent in October 2018 to 84 percent in July 2022. But that, really, is too specific a market: Amazon’s Alexa provides search powered by Microsoft Bing, and many consumers search within websites such as Amazon and Yelp for products, restaurants and more rather than using a general search engine first. Indeed, some young ‘uns even apparently use TikTok for searching for recipes or other content. Imagine!

Amazon and Apple

Now, the idea that other “Big Tech” companies such as Amazon and Apple could ever be deemed “monopolies” even in their core sectors just didn’t pass the sniff test. “E‑commerce retail” is not some distinct market from retail more broadly (obvious, given many companies do both), meaning Amazon’s competition was always fierce. Cloud services are the big profits generator for the company now, but as Figure 6 shows, the company faces meaningful global competition from Azure, Google Cloud, Alibaba Cloud and more. And this market is obviously global.

Amazon’s stock price has been suffering of late, almost halving in the past year. This decline after a period of exceptional growth could be down to some specific transitory factors (such as a tightening of consumer spending and high-cost inflation) after a period of strong pandemic growth. Again, though, it’s clear looking across sectors that Amazon faces significant competitive pressures in the largest markets it operates. Dominance is far from guaranteed, let alone their being obvious monopoly power.

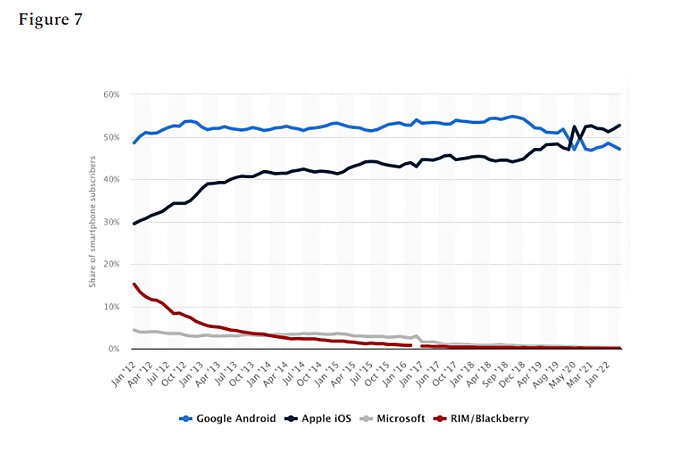

Apple is weathering the storm best of these major tech companies, but cannot be described as a monopoly either. Just two years ago, Apple’s iOS phone operating system actually trailed the use of Google’s Android in the United States (see Figure 7). Apple faces competition aplenty from other mobile and computer manufacturers too. The company has had to constantly innovate to maintain a strong market position in mobile and computers, while curating its ecosystem.

Conglomerate Competition

Why, then, is the term “monopoly” thrown around so much when it comes to these companies? I’ve written before that they seem to occupy “psychological monopoly” status in our political discourse. That is, their perceived pervasiveness in our lives — often operating across many different domains, — can make them feel like monopolies, even if they do not, in fact, monopolize any single economically relevant market.

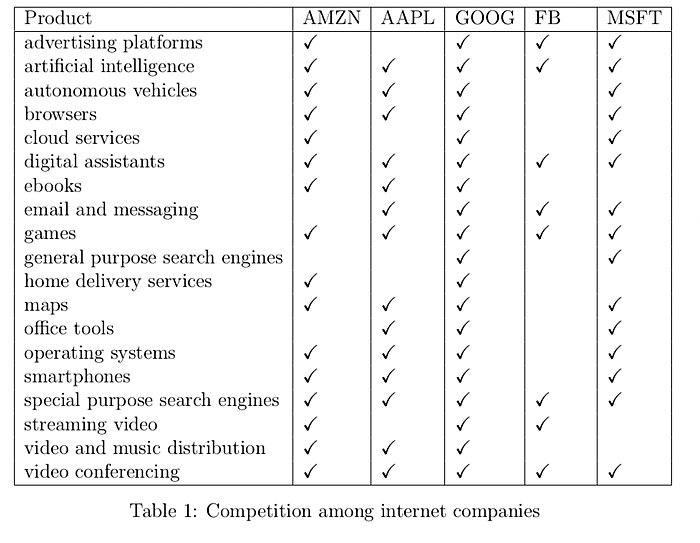

Take this table below from Google chief economist Hal Varian. It shows how Amazon, Apple, Google, Meta and Microsoft already compete in a ton of different markets. And it implicitly shows that these “Big Tech” companies are really more like big conglomerates these days, competing with each other across numerous markets at the same time. That much is obvious when you are given the option to “sign in” through many of them in using apps or other websites.

Being a conglomerate, of course, can diversify the risk of a business suffering from creative destruction in a core market, while creating internal capital markets that can help a company survive. The downside risk is that conglomerates can become unwieldy, inefficient businesses to manage, creating internal fiefdoms that compete for resources and take the business down rabbit holes.

Apple is weathering the storm best of these major tech companies, but cannot be described as a monopoly either. Just two years ago, Apple’s iOS phone operating system actually trailed the use of Google’s Android in the United States (see Figure 7). Apple faces competition aplenty from other mobile and computer manufacturers too. The company has had to constantly innovate to maintain a strong market position in mobile and computers, while curating its ecosystem.

Conglomerate Competition

Why, then, is the term “monopoly” thrown around so much when it comes to these companies? I’ve written before that they seem to occupy “psychological monopoly” status in our political discourse. That is, their perceived pervasiveness in our lives — often operating across many different domains, — can make them feel like monopolies, even if they do not, in fact, monopolize any single economically relevant market.

Take this table below from Google chief economist Hal Varian. It shows how Amazon, Apple, Google, Meta and Microsoft already compete in a ton of different markets. And it implicitly shows that these “Big Tech” companies are really more like big conglomerates these days, competing with each other across numerous markets at the same time. That much is obvious when you are given the option to “sign in” through many of them in using apps or other websites.

Being a conglomerate, of course, can diversify the risk of a business suffering from creative destruction in a core market, while creating internal capital markets that can help a company survive. The downside risk is that conglomerates can become unwieldy, inefficient businesses to manage, creating internal fiefdoms that compete for resources and take the business down rabbit holes.

Being very big with fingers in multiple pies, though, is not synonymous with monopoly power. Meta’s struggles and the evident innovation we are seeing in digital advertising and retail, as well as the branching out of all these businesses into so many markets, suggest that investors and these companies are far less certain of their dominance in core competencies than regulators claim.

When you hear someone talk about the Big Tech monopolies, ask them: “Monopolies of what?” For not only do the data show meaningful competition in economically meaningful individual markets, but recent rumblings suggest a very real risk that we will again see antitrust authorities raking these businesses over the coals just as the gales of creative destruction are honing in.

Other things

-

My Times column today was on the earth’s human population being projected to hit 8 billion on November 15th.

-

For The Dispatch, I wrote a full review of Sam Gregg’s excellent new book The Next American Economy.

-

For Discourse Magazine I wrote a summary of the downfall of Trussonomics.

-

And, a couple of weeks ago, I wrote about how some at the FTC are trying to reintroduce the terrible Robinson-Patman Act.

That’s all!