The stocks of rare earth companies soared Monday following news that the Trump administration had taken a 10% stake in Oklahoma mining and magnet company USA Rare Earth Inc. Such is the visible benefit enjoyed by the growing number of firms that count Uncle Sam as a shareholder. Yet recent events surrounding perhaps what is the most well-known state-picked champion, Intel Corp., exposed a major unseen cost of the federal government’s unprecedented intervention in private business: the distortion of capital markets that have underpinned American growth and innovation since its founding.

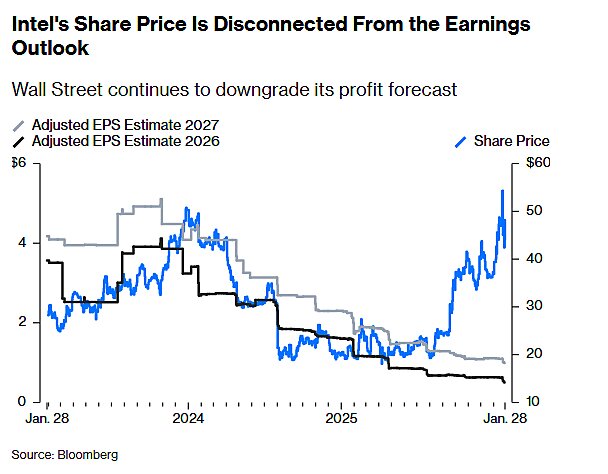

Prior to Intel’s January 22 call with analysts and investors to discuss its quarterly results, the Santa Clara, California-based semiconductor maker had been on a winning streak. Since the Trump administration announced in August that the government would take a 10% stake in the troubled company, its share price more than doubled, and it reached multibillion-dollar deals with SoftBank Group Corp. and Nvidia Corp. Speculation rose of contracts withApple Inc. and other tech heavyweights – essential for Intel’s advanced semiconductor foundry business and sparking optimism that the long-promised turnaround was underway.

Intel’s latest financial results burst that bubble, revealing many of the same challenges that have plagued the company for years, if not decades. On the earnings call, Chief Executive Officer Lip-Bu Tan said production yields for Intel’s own products “are still below what I want them to be,” and his ambiguity hinted that yields might be worse than the already-low numbers outsiders had assumed.

Poor yields and inexperience, meanwhile, have left the company’s foundry business — core to the Trump administration’s semiconductor strategy — mired in a chicken-egg quandary: large external customers won’t commit to using Intel’s most advanced “14A” chips until it demonstrates flawless mass production, but it can’t scale production without customers.

Intel still lacks a coherent strategy for artificial intelligence and continues to lose market share to rival Advanced Micro Devices Inc. And near-term revenue has suffered because a “stunningly bad strategic decision” to cut production capacity left Intel unable to meet surging CPU demand from AI data centers. Confronted with this cold reality, investors fled. Intel’s shares plunged 17% Friday and slid an additional 5% Monday.

Maybe Intel recovers in the months ahead, but the selloff shows how the Trump administration’s “state capitalism” experiment might be fueling significant and growing capital misallocation in the US today. Intel’s market capitalization exceeded $271 billion before Thursday’s earnings call, or more than $180 billion higher where it sat prior to the government’s investment. Last week’s events cut that figure by almost $60 billion as of Monday, a strong indication that the bulk of the initial gains were driven by politics and not capitalism. In other words, the government’s investment had diverted tens of billions of dollars of private capital away from potentially more deserving firms and to Intel, with little support for the move beyond – as one semiconductor analyst put it – “vibes and tweets.”

That’s textbook capital misallocation, and it goes beyond Intel. As of Monday, the Trump administration had taken a “golden share” in US Steel as a condition of the company’s sale to Japan’s Nippon Steel Corp., and took direct equity stakes in a dozen other private companies, spanning rare earth minerals, nuclear energy and defense. Share prices of these firms have zoomed higher, as we saw Monday with USA Rare Earth. The White House has promised more such equity deals are on the way, putting even more taxpayer dollars on the line and ensuring that capital flows to chosen firms and away from others only because Washington is involved.

Regardless of whether the government’s stock picks work out, the underlying economic distortions persist: Targeted companies suck up scarce resources for months or years – resources that could have gone to productive, well-performing alternatives. Meanwhile, unrelated investments become distorted as well. Bloomberg News reported in November that speculators have started “trying to think like Trump to find the next targets of the US government’s ownership stakes in public companies, which tend to see massive gains following the investment.” Some institutional investors now evaluate companies based in part on their “political relationship with the state.”

Capital misallocation causes lower productivity, weaker growth and a smaller, less vibrant economy over the long term even if state-backed champions don’t fail. According to new research from International Monetary Fund economists, Chinese industrial policy between 2010 and 2023 systematically diverted capital toward state-owned champions and politically favored private firms, rather than the nation’s most productive enterprises. This misallocation dragged down aggregate productivity by an estimated 1.2% and GDP by roughly 2%, if not more. For an $18.2 trillion economy like China’s in 2023, that translated to $364 billion in losses that year alone, which compounds to trillions of dollars over the entire period examined. Other research finds similar losses stemming from policy-driven capital misallocation in China and elsewhere, plus related harms such as “zombie” firms, reduced dynamism and corruption.

The US isn’t China, of course, but every Trump administration investment pushes it more toward that model and amplifies the inevitable distortions. And “national security” doesn’t justify the expense. There are better, safer ways to help strategic industries and boost American competitiveness than for Washington to take an opaque and open-ended stake in a private firm with taxpayer money. Some of these policies — lower corporate taxes, streamlined environmental permitting, freer trade in industrial inputs, expanded high-skill immigration – are market-based. Others involve government interventions such as long-term contracts and prizes. Yet they all allow markets to allocate capital to its best uses and greatly reduce the risk of politicized zombie companies absorbing resources, stifling innovation and sapping economic growth.

The US spent decades correctly lecturing the rest of the world on the harms of state capitalism, and our economy has thrived by avoiding such moves. Those facts don’t disappear when rebranded as “strategic investment,” and Intel’s meltdown shows where the road might lead: billions of dollars in losses, continued operational dysfunction and an economy increasingly warped by political rather than market forces.