With only three weeks until the big presidential election (thank goodness), now’s as good a time as any to grade President Trump’s economic policy during his first term. As you’d expect, my grades below are from a freer market perspective, but the facts supporting them apply regardless of whether you see these changes as “good” or “bad.” Overall, I think that Trump did OK in some areas and horribly in others (which you can probably guess in advance)—essentially reflecting the persistent conflict in the White House (and the entire GOP) between “traditional” conservatives who support more open markets and upstart economic nationalists. (A conflict, it should be noted, that probably undermined the efficacy of each team’s favored policies.)

Before I begin, however, three words of caution: First, it is extremely difficult—particularly when you’re dealing with a diverse, globalized, $20 trillion economy with a powerful and mostly independent central bank—to make a causal connection between specific policies and subsequent changes in economic trends. Second, other U.S. institutions, particularly Congress and the Federal Reserve, of course play a role in shaping U.S. economic policy and performance, but presidents still matter: Politically, they always get more credit or blame than they deserve; substantively, they appoint Fed policymakers, strongly influence party policy (probably too much), and still have to sign or veto legislation. So, yes, Trump didn’t do this all himself, but his administration certainly played a leading role and didn’t hesitate to take credit when things were going well.

Finally, there’s the question of what to do about COVID-19—a once-in-a-lifetime (hopefully) situation that almost everyone believed required a once-in-a-lifetime (again, hopefully) economic policy response. In general, I plan to be nice and evaluate Trump’s economy before COVID (thus not blaming the administration for the economic collapse or massive increase in spending), though it certainly must be mentioned when we get into the weeds of certain policy moves that have arisen in response to the pandemic (and could very well be with us for many months or years thereafter).

Now onto the grades.

Fiscal Policy: C

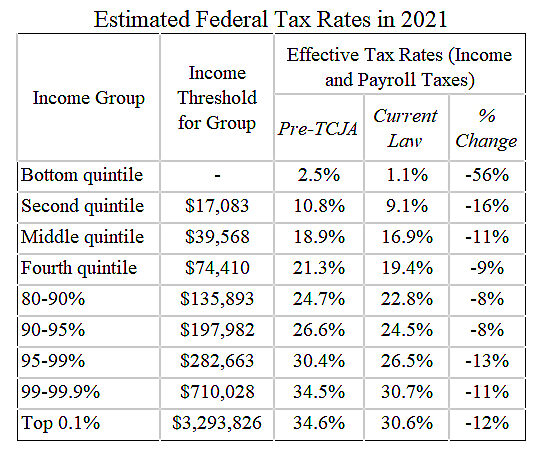

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA)—arguably Republicans’ signature economic achievement during Trump’s term—was hardly perfect but it did several good things, particularly by reducing the United States globally uncompetitive corporate tax rate and allowing for limited immediate “expensing” of business investments. On the personal side, the TCJA had some improvements (and some problems). In general, it lowered effective tax rates for all groups, but definitely not everyone within those groups. Cato’s Chris Edwards shows below how the bill actually changed effective tax rates. (Spoiler: It wasn’t a massive giveaway to “the rich,” though certain upper middle-class taxpayers saw smaller effective reductions than 1 percenters.)

After the TCJA went into effect, total taxes collected did actually increase in 2018 and 2019 by tens of billions of dollars, but these revenues remained significantly lower than what was projected without the TCJA. Thus, one really can’t legitimately claim that tax cuts “paid for themselves,” but they also didn’t cause revenues to collapse or the deficit to explode. (The problem, as we’ll discuss next, is the spending—as always.)

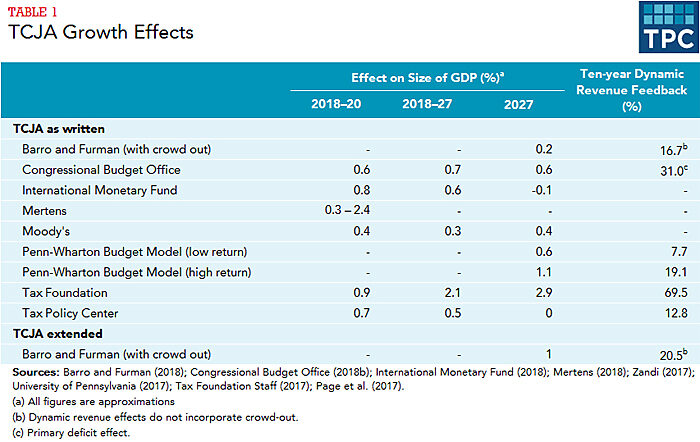

In terms of economic effects, the Tax Policy Center summarizes the general consensus: modest short-term growth, with some long-run effects TBD.

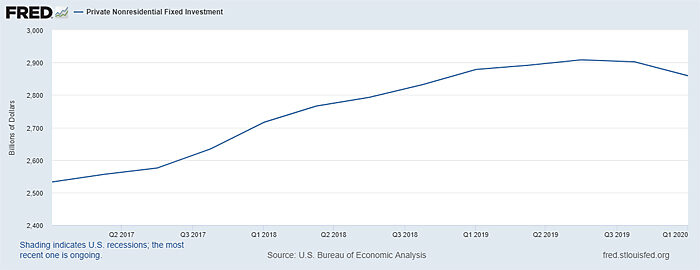

In terms of business investment, the results have been generally disappointing: The TCJA was supposed to strongly encourage corporations to invest in the United States, but there was only significant increase for a few months, and then business investment slumped again:

Foreign direct investment also picked up a little in 2018, only to fall significantly in 2019. Whether this is a failure of the TCJA or indicative of other things (like Trump’s trade wars), however, is unclear.

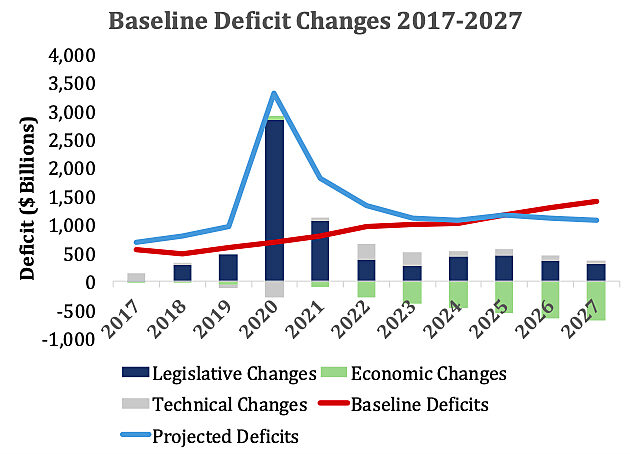

Things are far clearer, however, on the spending side, where Trump gets much lower marks—not just continuing past spending trends but actually accelerating them a bit (pre-COVID). I documented most of these spending trends in my recent newsletter edition on “Libertarian Economics,” but here’s one more chart just to hit things home:

Prior to the pandemic, 2020 outlays were projected to be about the same (about 21 percent of GDP) as 2019, and then increase significantly thereafter (to 23.4 percent by 2030). COVID, of course, has deteriorated the situation significantly. The American Action Forum’s Gordon Gray provides a little more on how all of this spending (and the aforementioned tax cuts) affect the deficit in his summary of the latest Congressional Budget Office (CBO) data:

“Combined, according to CBO data, over the period 2017–2027, legislation signed by President Trump increased projected deficits by $6.9 trillion. Over the same period, economic factors, particularly substantially reduced projected interest costs, have reduced projected deficits by just under $3.2 trillion. Technical factors have contributed a combined $770 billion in reduced projected deficits over the same period.”

Economic consensus has definitely shifted in the last couple decades about the urgency of the federal debt, but it still matters in the long run. If Trump were seriously resisting or reforming any of this—literally any of it—one might be inclined to grade him on a curve here, but he most certainly isn’t. That fact, combined with Republicans’ concurrent abdication of their already-meager spending concerns, is why the pretty good tax reforms are essentially canceled out by the quite bad spending and debt situation.

Regulation: C

The Trump administration certainly enjoyed a few easy victories on the regulation front in 2017 and 2018 (e.g., the Clean Power Plan), and most definitely slowed the Obama administration’s regulatory steamroller overall. I think it’s fair to say that the administrative state would have been larger—perhaps by a significant degree—if Hillary Clinton had won in 2016. However, as I noted here a couple weeks ago, the general historic trend toward increasing federal regulation has continued relatively unabated during the Trump years, and many major deregulation moves have been matched by new and unwieldy regulatory initiatives (e.g., the USTR and Commerce Department tariff “exclusion” systems, which have cost tens of thousands of U.S. companies ample sums—trust me on this—trying to successfully navigate them). The administration has also defended an expansive definition of regulatory power in the courts, reflecting its desire to use that power to bypass Congress and pursue their economic nationalist, populist agenda via agency diktat.

As Reason’s Matt Welch explained a few days ago, moreover, it’s not just trade and immigration getting the bureaucratic whip:

The president’s trade record and hands-on approach to industrial policy threaten to overrun one of the best aspects of his first term—his conscious, system-wide slowdown of the ever-expanding administrative state.

“Trump’s regulatory streamlining,” the Competitive Enterprise Institute stated in May in its annual regulations survey The Ten Thousand Commandments, “is being offset by his own favorable comments and explicit actions toward regulatory intervention in the following areas: Antitrust intervention, financial regulation, hospital and pharmaceutical price transparency mandates and price controls, speech and social media regulation, tech regulation, digital taxes, bipartisan large-scale infrastructure spending with regulatory effects, trade restrictions, farming and agriculture, subsidies with regulatory effect, telecommunications regulation, including for 5G infrastructure; personal liberties: health-tracking, vaping, supplements, and firearms; industrial policy or market socialist funding mechanisms (in scientific research, artificial intelligence, and a Space Force), [and] welfare and labor regulations.”

And while the administration can boast a “regulatory budget” that saved billions of dollars in compliance costs, most of the savings is a mirage because many expensive regulations were exempt from the calculation. Indeed, one such regulation—related to cybersecurity—“could impose roughly $92.8 billion in total costs on the public,” write Dan Bosch and Dan Goldbeck for American Action Forum. Include these regulations, and the Trump administration is just treading water.

Jobs: B

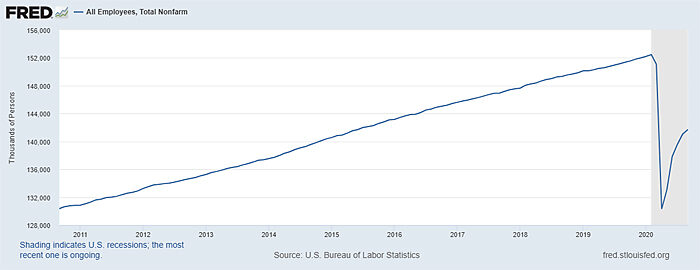

No, presidents don’t deserve much credit for creating American jobs, but employment is an important economic (and political) metric and, for the first three-plus years at least, the jobs situation in the Trump era was pretty darn good. This is especially the case on wages, which ticked up noticeably in 2018 and 2019 due to the tight (very tight) labor market and the economic “sugar high” created by the aforementioned fiscal policies (tax cuts and spending).

That said, it’s difficult to give the administration anything higher than a B here for three important reasons, all shown in the following two charts:

First, the jobs situation was essentially one of continuing, not special, strength—for both total employment and manufacturing jobs (which everyone—especially Trump—seems to care about). In short, Trump inherited a good jobs market from Obama and then goosed it a little more with some fiscal (and probably regulatory) policy. Second, his trade wars—which we’ll discuss below and for which he is solely responsible—had a noticeable impact on those precious manufacturing jobs, helping to stall them out in 2019 after two solid years of strong growth and more than a decade of relatively steady post-recession gains. Third, there’s COVID-19 and our current mess of a labor market: Trump’s not the only one to blame here, but if we’re giving him credit for the boom times, he owns some of the recession too (and, quite frankly, his administration’s bungling has probably made things worse).

Entitlements: D+

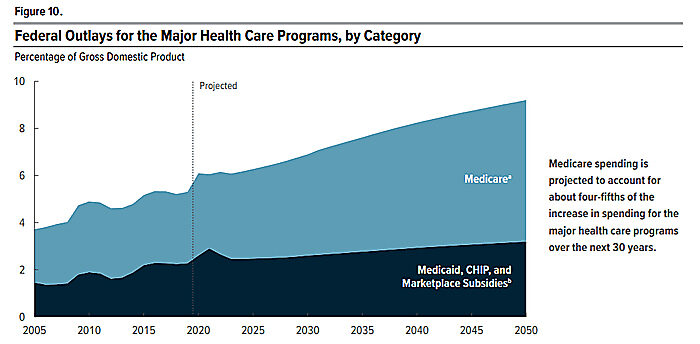

Yes, they claim they want freer market alternatives to Medicare for All, but they’ve actually given us a few modest cuts to Obamacare, some worthless talking points about “America First health-care,” a total mess on prescription drugs, and this unceasing reality:

Meanwhile, the latest news is that the Trump administration is preparing to send seniors $200 Trump cards “resembl[ing] credit cards” that “would need to be used at pharmacies and could be branded with a reference to Trump himself.” The cards would “be paid for by tapping Medicare’s trust fund.” (But watch out for socialism, you guys!)

As the Heritage Foundation notes, moreover, the situation with other entitlement programs isn’t looking so hot and has been exacerbated by the current economic downturn:

- Social Security’s retirement trust fund will become insolvent in 2031. Absent reforms, “all retirees would experience a roughly 25% reduction in benefits” that year.

- Social Security’s Disability Insurance fund will run out in 2026.

- Medicare Part A (hospital insurance) “will consume its remaining funds by 2024.”

In Trump’s defense, he campaigned on not cutting Social Security or Medicare, so … promises kept, I guess. Congrats.

Trade: D-

I’ve already given you 2,000+ words on why the core of Trump’s trade policy—tariffs—has been a disaster, so I’ll just focus on two other things here. First, President Deals hasn’t actually been much of a dealmaker at all. Beyond the mess of the Phase 1 Deal with China, he has:

- Tweaked the automotive provisions of the Bush-era U.S.-Korea FTA, primarily by extending U.S. tariffs on Korean trucks by another 20 years.

- Signed and implemented the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which maintained most of the Clinton-era NAFTA, added much of the Obama-era Trans-Pacific Partnership (on things like digital trade), threw in some Trumpian protectionism and industrial policy (especially on automobiles), and then added House Democrats’ (and lawyers’ and labor unions’) dream restrictions for labor and environmental enforcement. The result: a Frankenstein deal that Canada and Mexico reluctantly implemented just to get Trump to leave them alone, and one that actually reduces annual U.S. GDP unless you include the absurd contention that the deal eliminated uncertainty in the North American supply chain. (Spoiler: It did not.)

- Implemented a limited “Phase 1” agreement with Japan, which basically just cut-and-pasted the Japanese tariff commitments in Obama’s TPP, but only for U.S. farm goods. Only 25 more chapters to go!

- Taken America’s ball and gone home at the WTO, choosing to shut down the organization’s appellate body (basically the supreme court of trade dispute settlement) instead of negotiating new and necessary reforms in good faith (e.g., by teaming up with like-minded countries while offering actual concessions on longtime irritants like U.S. agricultural subsidies and “trade remedy” rules).

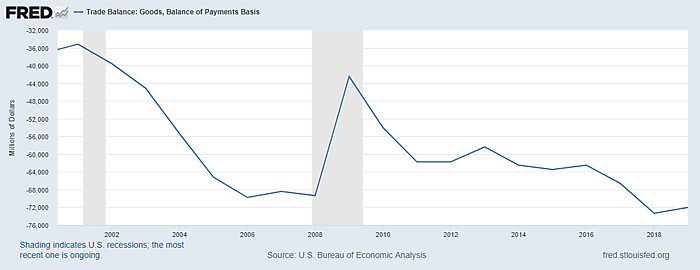

Second, the president has failed by his own primary standard for judging U.S. trade policy, the United States’ goods trade deficit:

The monthly deficit has actually increased further in recent months, but hitting Trump on that is (in my opinion) a bit disingenuous because the pandemic has really messed with global trade flows. Regardless, the pre-pandemic data are clear: The goods deficit was about $750 billion in 2016, and it was $864 billion in 2019—just a hair below its 2018 record. That’s “failure.” Big league.

Now, as we’ll surely discuss in a future column (and as Kevin Williamson discusses here), grading U.S. trade policy with a trade balance scorecard has always been an idiotic thing to do because balances are dictated by global macroeconomic factors, not trade deals or tariffs. But that’s not what the president and his closest advisers said over the last four years, so—at least as a political matter—they deserve to be hoisted with this rather foolish petard.

Immigration: F

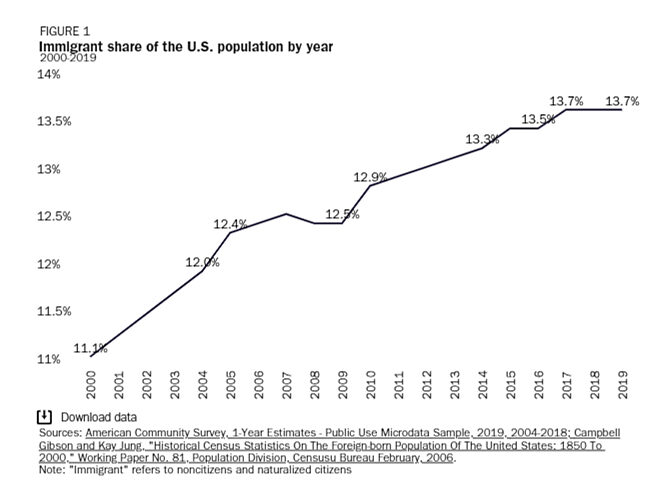

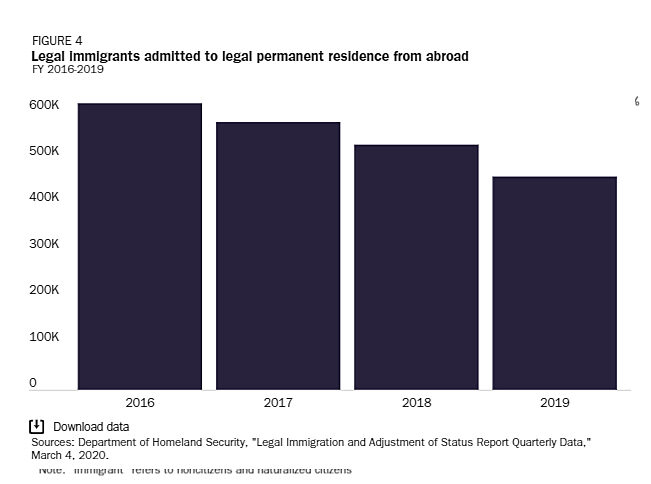

I struggled with whether the president’s immigration policy should grade worse than his trade policy, but feel obliged to conclude that it should. On trade, the president has implemented a bunch of bad policies and said a bunch of stupid things, but he hasn’t been able to cut the overall level of goods and services imports (which are up significantly since the Obama years). Not so with immigration, where Trump’s pre-COVID attacks on legal immigration—low-skilled, high-skilled, students, family members, refugees, entrepreneurs, etc.—have actually succeeded in reducing annual immigration levels and flatlining the country’s foreign-born population:

Then there are the inhumane detention policies; the travel ban; the Deportation Force; the “emergency”blockades due to COVID-19; the new, mathematically-challenged move to further restrict high-skill immigration (much to China’s benefit); and the various ways that the administration has bent or broken the law to push his restrictionist dreams (funding The Wall, banning asylees, threatening “emergency” tariffs to stop The Caravan, etc.). Combine that with the nativist (at best) rhetoric, and you wind up with a big, fat, much-deserved F.

The only bright side is that increased immigration has never been more popular. So we’ve got that going for us, which is nice.

Summing it all up.

These grades would prevent President Trump from graduating from Lincicome University (which has more rigorous standards than the SEC), but certainly require additional context. On the positive side, there’s little doubt that some things—fiscal and regulatory policy, in particular—would have been worse under a President Clinton. On the negative side, however, Clinton almost certainly would have been better on trade and immigration, while overall having a more consistent, predictable, and coherent approach to policymaking in general. This last point really can’t be undersold, given the extensive research (see, e.g., this brand new one) showing how policy uncertainty can undermine economic activity. And there, I think, is where the Trump administration has really failed: for the last four years, formal U.S. economic policy has all too often resulted from frantic, messy attempts by beleaguered government officials to “backfill” disconnected policy trenches dug by presidential tweets. That’s no way to run economic policy, and it shows.

Chart of the Week

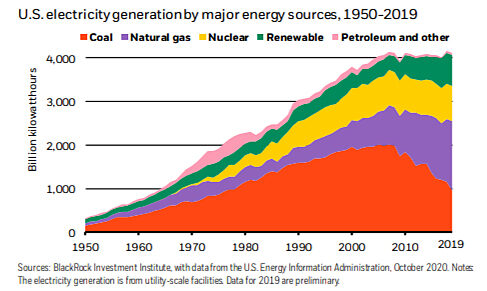

Natural gas’s War on Coal (source):

The Links

Me on taxes, transfers, and incomes

Reuters deep-dive into the failures of Trump’s tariffs in Michigan

Large city centers are struggling, but hiring elsewhere has surged

“The true size of government is nearing a record high”

How five American small businesses retooled to make PPE and survive the pandemic

Tariffs or no, China’s shipping a LOT of PPE to the USA

The Long History of Official Lies about Presidential Health

On the winners of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Economics

“Months before travel bans and lockdowns, Americans were transmitting the virus across the country”

How many companies/jobs depend on trade in your state?

“Why pro-growth economics is about connections, networks, and trust”