Dear Capitolisters,

Fueling Uncertainty

We need more refinery capacity but policy uncertainty makes companies less inclined to invest in new refineries or update old ones.

I was never a very eager student in law school but did absorb a few enduring lessons in between all the video games and beer pong. One of them came during a corporate law class, in which the professor emphasized repeatedly that, while companies and investors surely care about a law’s substance (e.g., tax rates or whatever), they care more that the policies are crafted and applied in a consistent and predictable manner over time. In short, market actors—especially the big boys—can adjust to and plan for almost anything (and respond accordingly), as long as said thing is relatively sure to happen. High levels of economic and policy uncertainty, on the other hand, are simply a killer—invoking paralysis in a company and, by extension, the economy.

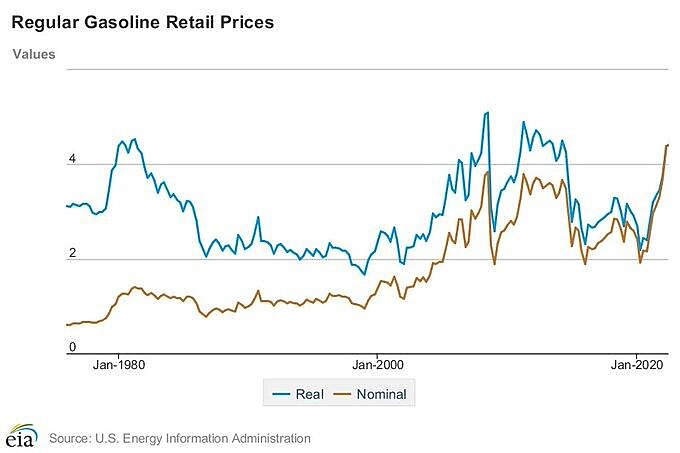

I force you to endure this long windup because I’ve been thinking a lot about that law school lesson—and policy uncertainty more broadly—the recent political drama about U.S. gas prices, which in case you haven’t noticed are pretty high right now (though still off inflation-adjusted highs):

Given gas prices’ political importance in the United States (for better or worse)—amplified today by broader inflationary pressures—the Biden administration has reportedly been scrambling to find a few policy levers it can pull to lower prices over the high-demand summer driving months. Just today, the president called on Congress and states to suspend gas taxes. He also just sent a sternly worded letter to major U.S. oil refiners, accusing them of profiteering during a global energy crisis and calling on the companies to produce more gasoline and diesel… or else. From the Associated Press:

The letter notes that gas prices were averaging $4.25 a gallon when oil was last near the current price of $120 a barrel in March. That 75-cent difference in average gas prices in a matter of just a few months reflects both a shortage of refinery capacity and profits that “are currently at their highest levels ever recorded,” the letter states….

“There is no question that (Russian President) Vladimir Putin is principally responsible for the intense financial pain the American people and their families are bearing,” Biden’s letter says. “But amid a war that has raised gasoline prices more than $1.70 per gallon, historically high refinery profit margins are worsening that pain.”

The letter says the administration is ready to “use all reasonable and appropriate Federal Government tools and emergency authorities to increase refinery capacity and output in the near term, and to ensure that every region of this country is appropriately supplied.” It notes that Biden has already released oil from the U.S. strategic reserve and increased ethanol blending standards, though neither action put a lasting downward pressure on prices.

According to various sources, the short-term “tools” under consideration by the White House and congressional Democrats include the aforementioned gas tax break (which would have uncertain economic effects), plus a hodgepodge of good (Jones Act waivers) and mostly terrible (gas rebate cards, price controls, export restrictions, invoking the Defense Production Act) ideas. Some of this, like the gas tax, would probably require Congress, but much of it wouldn’t—as the letter’s nod to “emergency authorities” makes clear.

Unfortunately for the Democrats and American drivers, however, there’s not really all that much that can be done about the overall gas price situation in the next few weeks or even months. For example, waiving the Jones Act is probably the best policy solution out there right now, but estimated savings for affected drivers on the East Coast would be maybe $0.10 per gallon—worth doing, yes (obviously!), but not a major game changer and, perhaps most importantly, not affecting gas prices’ overall trajectory. Instead, the bigger picture will continue to be driven by good ol’ supply and demand, with the former being the biggest problem in this case.

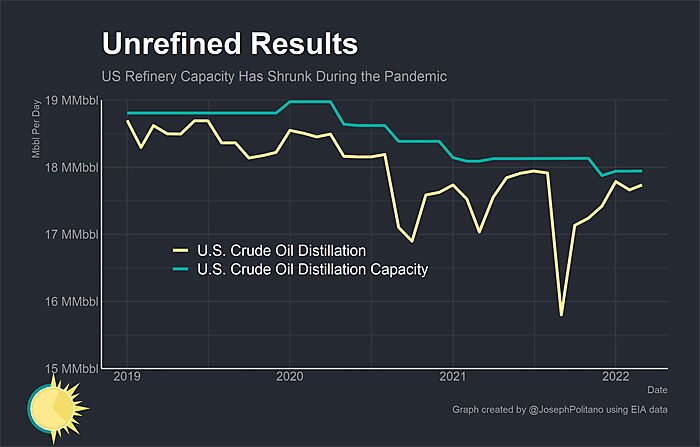

In particular, U.S. gasoline prices have been affected greatly in recent months by a lack of domestic and global refinery capacity. Some of the capacity crunch has been caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and related sanctions, which took as much as 30 percent of Russia’s capacity offline, as well as unplanned and seasonal maintenance around the world. As Bloomberg explained back in May, however, a big part of the supply crunch is the recent and planned closures of numerous refineries in the United States:

More than 1 million barrels a day of the country’s oil refining capacity — or about 5% overall — has shut since the beginning of the pandemic. Elsewhere in the world, capacity has shrunk by 2.13 million additional barrels a day, energy consultancy Turner, Mason & Co. estimates. And with no plans to bring new US plants online, even though refiners are reaping record profits, the supply squeeze is only going to get worse.

The article goes on to explain that, when the pandemic collapsed demand for gasoline and jet fuel in 2020, refiners “closed some of their least profitable crude-processing plants permanently.” And more U.S. refinery closures are on the horizon: “By the end of 2023, as much as 1.69 million barrels of US capacity is targeted for closure compared to 2019 levels, according to Turner, Mason & Co.”

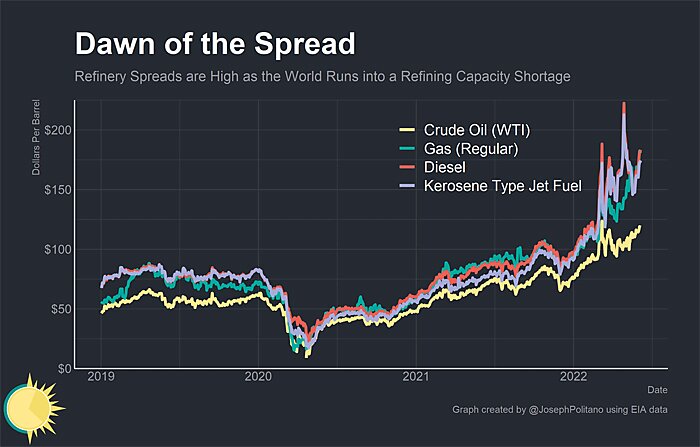

As economist Joseph Politano explains, the U.S. is a key part of the global equation for most refined products because we’re a big exporter:

US refinery capacity steadily decreased about 5% since 2020 thanks to planned closures and relatively weak demand. Since the US is a net importer of crude oil and a net exporter of refined products, domestic refinery capacity is essential for global energy supply. A fire at a facility in Houston could bring more unwelcome news—possibly accelerating the planned closure of a facility that alone represents about 1% of US refinery capacity.

It’s thus no surprise, then, that recent declines in U.S. refinery capacity and output …

… have caused refined products, including gasoline, to decouple from—and increase more quickly than—crude oil prices here (WTI):

The lack of new U.S. refinery investment isn’t exactly breaking news: According to the EIA, for example, the last major refinery to be built in the United States was in 1977, while there hasn’t been a significant refinery expansion in several years. But, still, the recent decline in national refining capacity remains quite stark when you compare it to pre-pandemic trends dating back decades:

So why, then, in a time of clear supply/demand imbalance and high prices are refineries not expanding and investors not jumping in?

First, a Word on Uncertainty

Before we get to that, let’s first go over the basics on economic uncertainty. In general, there are two types of macroeconomic (not firm-specific) uncertainty. First, there’s just your everyday general economic risks—recessions, natural disasters, foreign wars, changing consumer tastes, innovations, etc.—that policymakers and individuals can try to prepare for and mitigate but really can’t dictate. Then there’s policy uncertainty—election-related turnover; new, changing, or unclear laws and regulations; temporary measures; discretionary executive actions; etc.—that are, for the most part, under policymakers’ direct control. Congress can, for example, make an agriculture law clear, detailed, and permanent, but it can’t, say, prevent tornadoes and floods. (That I know of!)

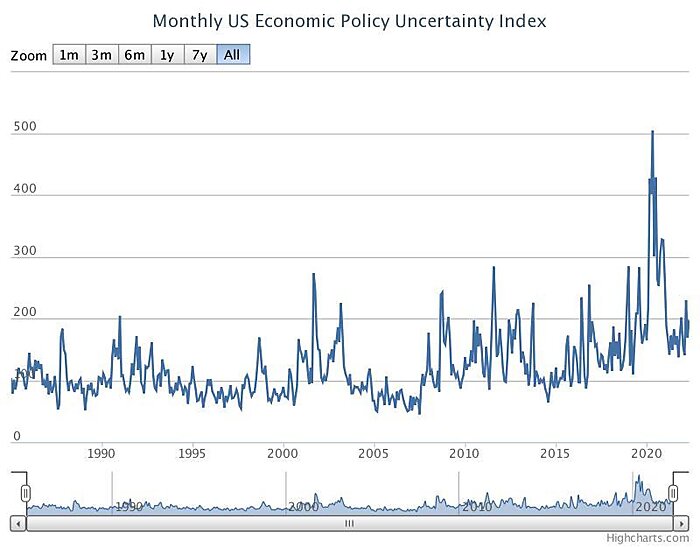

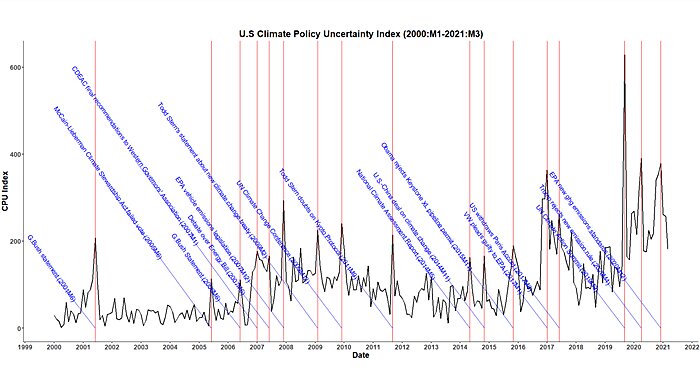

Economists have created various indices to measure both types of uncertainty over time, by looking at various publications’ mention of words like “uncertain” and other factors. As this annotated version of the World Uncertainty Index shows, uncertainty has increased in recent years, with both natural and man-made events causing big spikes:

There are also indices for certain countries and certain types of uncertainty, including economic policy, climate policy, trade policy (which has skyrocketed lately—gee, I wonder why), and monetary policy. The U.S. economic policy uncertainty index is particularly interesting:

This index incorporates not only media headlines but also the number of federal tax code provisions set to expire and disagreement among economic forecasters.

My old law professor was mainly interested in this type of policy uncertainty, and rightly so: As summarized in a useful 2019 paper on the subject, there is a deep library of scholarship on how policy uncertainty hurts economic performance, especially business investment. In particular—

[A] variety of studies find evidence that high (policy) uncertainty undermines economic performance by leading firms to delay or forego investments and hiring, by slowing productivity-enhancing factor reallocation, and by depressing consumption expenditures. This evidence points to a positive payoff in the form of stronger macroeconomic performance if policymakers can deliver greater predictability in the policy environment.

Subsequent studies have reinforced these findings (see, e.g., here, here, and here). In short, businesses invest less (or not at all) when policy uncertainty rises.

Now Back to Refineries

And this brings us back to refinery investment, where both types of uncertainty are likely at play. As the aforementioned Bloomberg article explains, nobody is investing in new U.S. refinery capacity or even keeping up old refineries because they don’t think their investments will pay off: Building a new plant costs billions of dollars and takes 15 to 20 years to turn a profit; and even fixing up old refineries can cost $1 billion or more (especially in the current inflationary environment). Thus, U.S. refiners are closing down old plants and not buying newer ones: As Valero’s CEO said recently, “We feel we’ve got higher returns, better uses for the capital to employ than buying a refinery that’s on the market at this point in time.”

Several of the factors affecting these decisions are out of policymakers’ control: Obviously, there are a lot of global, systemic things—consumer demand, geopolitical conflict, etc.—affecting refineries and investors’ willingness to expand them in 2022. However, there are plans for refinery expansions in other parts of the world, and, in the United States at least, policy—and policy uncertainty—is likely playing a role in the lack of new investment. Over the longer term, for example, past research from the Cleveland Fed shows that “increases in uncertainty are associated with delays in capital investment projects” for U.S. refineries, and domestic energy and climate policy have been highly uncertain for the last several decades, repeatedly vacillating between oil-embracing Republicans and oil-shunning Democrats. The on-again, off-again (and on-again and off-again) drama with the KeystoneXL pipeline is a perfect example of this unsettled policy environment, as are the Paris climate deal and Obama’s Clean Power Plan. In all cases, uncertainty was heightened by the fact that decisions were being made by the executive branch alone, thanks to congressional inaction and discretion afforded the president by Congress and the courts.

This stuff adds up. New research shows, in fact, a substantial uptick in U.S. climate policy uncertainty in recent years:

The study’s author finds that this heightened climate policy uncertainty is associated with lower CO2 emissions and suggests future research on how it affects firm-level investment in climate-sensitive industries like energy. But it would seem obvious (to me, at least) that uncertainty plays a role in refinery investment over the longer term too: If it takes 15–20 years to recoup a refinery investment and there’s a big-but-unclear risk that climate regulation will make said investment unprofitable in only a decade or sooner (see, e.g., California), then you’re probably not making that investment.

Recent Biden administration proposals (and trial balloons) are likely adding to this uncertainty in the immediate term. When Biden first came to office, he was all gung ho on discouraging fossil fuel production and boosting renewable energy and electric vehicles. Now, however, he wants U.S. refiners “to increase refinery capacity and output in the near term” and is trying to lower gas prices (which would encourage more consumption). Further confounding market signals is the fact that several of the proposals apparently under consideration or being pushed by vocal administration allies—price controls, export restrictions, a windfall profits tax, etc.—would directly discourage additional domestic investment and production. As Don Boudreaux succinctly explains with respect to export restrictions (which also raise practical concerns)—

The greater are energy producers’ abilities to export, the larger are their markets for domestically produced energy and, thus, the greater are their incentives to invest in domestic exploration, drilling, and refining. While forcibly curtailing fuel exports … might decrease the prices that we Americans pay for gasoline today, the resulting reduced investment in domestic fuel production will ensure that we pay inordinately higher prices in the future.

(Indeed, it was the flipside of this calculus that led Congress and the Obama administration to lift the ban on crude oil exports a decade ago.)

Biden’s threats to commandeer production or impose price controls also increase the risk of the investments at issue, as Pierre Lemieux explains:

The only way private oil companies can find it profitable to increase production is if the price they get and their profits rise in the short term. In the long term, of course, their excess profits will be competed away on a free market. If they fear that their temporary excess profits will be expropriated, they will never increase production, neither today nor at the next emergency; or they will do it out of fear of “their” government, but don’t expect much efficiency from coercion.

I doubt that the Biden administration will follow through with these crazy ideas, but that’s not really the point. Instead, the mere possibility of such unilateral actions—left open by not only anonymous reporting but also vague and open-ended threats by the president himself—all but ensures that no sane company or investor will go anywhere near the U.S. refining industry right now.

Would you?

Summing It All Up

Reasonable minds can differ about the proper U.S. climate and energy policy, but we all can hopefully agree that it’s been an erratic, kludgy mess for well over a decade—a situation likely contributing to our current dearth of domestic refinery capacity and caused by a Congress that’s implemented an incoherent heap of temporary subsidies and mandates and delegated much of U.S. energy policy to a frequently-changing executive branch. Some of the price crunch here may ease in the coming months as new or idled refinery capacity comes back online outside the United States—especially in the Middle East and Africa (thanks, free trade!). Until then, however, we should expect gas prices to remain somewhat elevated—thanks in no small part to past U.S. policy decisions and indecision.

No amount of presidential jawboning and gimmickry will change those longer term policy dynamics, which unfortunately extend well beyond domestic energy and climate policy to tax, trade, agriculture, and pretty much every other economic issue area Congress has touched in recent years. Lessons (as usual) abound, but maybe the one thing that is certain in Washington these days is that no one in the government will learn them.

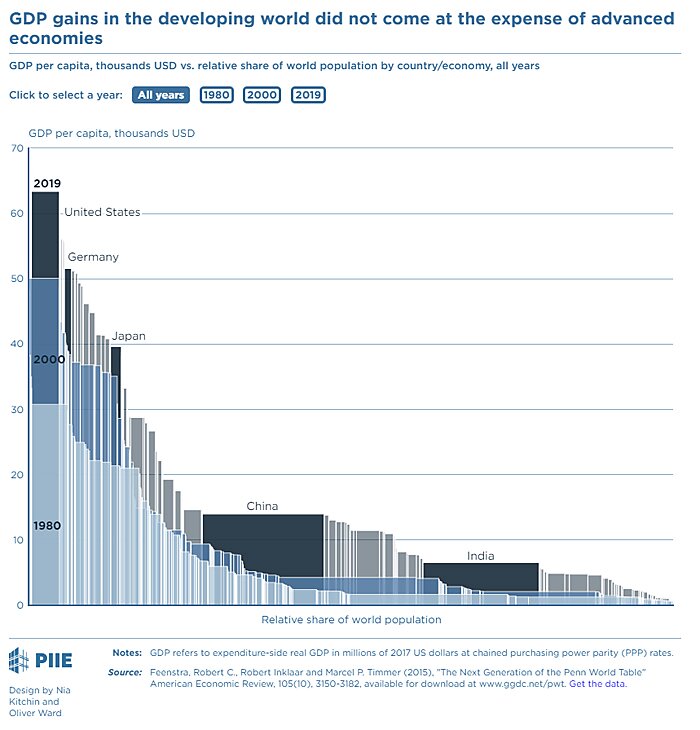

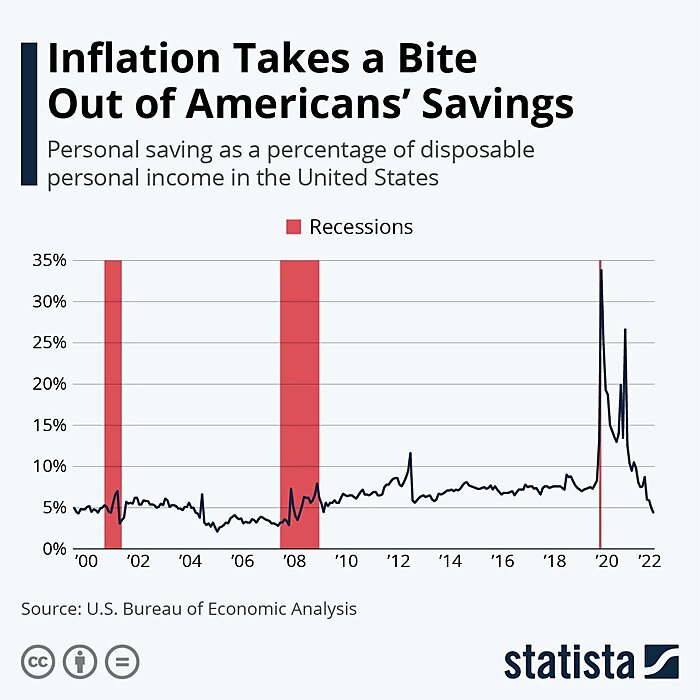

Chart(s) of the Week

The Links

My new paper on reforming the law Trump abused to slap tariffs on Chinese imports

For those who asked, here’s my Senate testimony on infant formula

Maersk chief: deglobalization isn’t happening

New US shipping law won’t do much to address soaring cargo costs

Tax burdens drive American expats to consider ditching U.S. citizenship

U.S. tariffs increased public support for protectionism and “self-reliance” in China

“Automate and modernize SoCal’s ports for the good of us all” (related)

“There are going to be discounts like you’ve never seen before”