How on Earth can anyone vote for that … [fill in the blank]? This is a question some Americans ask during every presidential primary race, but this year our mutual incomprehension feels especially intense. A year ago, Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush were expected to be the frontrunners, but now a senator from the far right (Ted Cruz) and a political neophyte from no known political zip code (Donald Trump) have come in first and second among Republicans in Iowa, taking more than 50 percent of the vote between them. On the Democratic side, an avowed socialist essentially tied with Clinton. What is happening?

Political scientists and commentators have a standard toolbox they use to explain elections, including variables such as the state of the economy, changing demographics, and incumbency fatigue. But this year, the standard tools are proving inadequate. Experts are increasingly turning to psychology for help. A recent article in Politico was titled "The One Weird Trait that Predicts Whether You're a Trump Supporter." It argued that the psychological trait undergirding Trump's popularity is authoritarianism — a personality style characterizing people who are particularly sensitive to signs that the moral order is falling apart. When they perceive that the world as they know it is descending into chaos, they glorify their in-group, become highly intolerant of those who are different, and feel drawn to strong leaders who promise to fix things, and who do not seem shy about using force to do so.

But now that Trump has lost in Iowa, there is increasing interest in the moral and psychological profiles of those who support other candidates. Iowa entrance polls showed that Cruz took the lion's share of voters who said it was most important to elect a candidate who shares their values. But what are those values, exactly? Is that just code for "evangelical Christian?"

On the Democratic side, Sanders attracts supporters who are younger, whiter, and further to the left — but is that all there is to it? What are socialist values, anyway? Can authoritarianism tell us anything about the supporters of these other candidates, or do we need other instruments, with finer resolution?

What is Moral Foundations Theory?

We'd like to add another psychological tool to the toolbox: Moral Foundations Theory. One of us (Haidt) developed the theory in the early 2000s, with several other social psychologists, in order to study moral differences across cultures. Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) draws on anthropology and on evolutionary biology to identify the universal "taste buds" of the moral sense, while at the same time explaining how every society creates its own unique morality.

Think of it like this: Evolution gave all human beings the same taste receptors — for sweet, sour, salt, bitter, and umami (or MSG) — but cultures then create unique cuisines, constrained by the fact that the cuisine must please those taste receptors. Moral foundations work much the same way. The six main moral taste receptors, according to MFT, are:

- Care/harm: We feel compassion for those who are vulnerable or suffering.

- Fairness/cheating: We constantly monitor whether people are getting what they deserve, whether things are balanced. We shun or punish cheaters.

- Liberty/oppression: We resent restrictions on our choices and actions; we band together to resist bullies.

- Loyalty/betrayal: We keep track of who is "us" and who is not; we enjoy tribal rituals, and we hate traitors.

- Authority/subversion: We value order and hierarchy; we dislike those who undermine legitimate authority and sow chaos.

- Sanctity/degradation: We have a sense that some things are elevated and pure and must be kept protected from the degradation and profanity of everyday life. (This foundation is best seen among religious conservatives, but you can find it on the left as well, particularly on issues related to environmentalism.)

As with cuisines, societies vary a great deal in the moralities they construct out of these universal predispositions. Many traditional agricultural and herding societies rely heavily on the loyalty, authority, and sanctity foundations to create rituals, myths, and religious institutions that bind groups together with a strong tribal consciousness.

That can be highly effective for groups that are often attacked by neighboring rivals, but commercial societies (such as Amsterdam in the 17th century or New York City today) are far less in need of these foundations, and so make much less use of them.

Their moral values, stories, and political institutions flow more directly from the liberty and fairness foundations — well suited to a culture based on exchange and production — and are therefore much more tolerant and open to ethnic diversity.

In recent years, MFT has been used to study political differences between the American left and right. Republicans and Democrats in the United States are now in some ways like citizens of different countries, with different beliefs about American history, the Constitution, economics, and climate science. Using questionnaires, text analyses, and other methods, psychologists have found that progressives put more emphasis on the care foundation than do other groups, while social conservatives see more value in loyalty, authority, and sanctity than do other groups. Libertarians, meanwhile, put liberty far above all other moral concerns.

Fairness, important to all groups, nonetheless has subtypes: The left values fairness more when it is presented as equality, particularly equality of outcomes between groups (which is at the heart of social justice). The right values fairness more than the left when it is presented as proportionality — a focus on merit, which includes a desire to let people fail when they are perceived to have been lazy or otherwise undeserving.

But these are broad-brush generalizations. Each person has a unique morality developed over the course of a lifetime. Each political party is a coalition of interest groups and political philosophies that appeal to people with diverse values. In the chaos of this political season, can MFT help us find some order? Can it improve our ability to predict which people will gravitate to which candidate, over and above the predictions we can make from standard variables such as age, race, gender, education, and self-ratings on the liberal-conservative dimension?

Our study

In November 2015 one of us (Ekins) was part of a team that surveyed 2,000 Americans as part of a Cato Institute/YouGov national public opinion study. The study included a battery of questions measuring each of the six moral foundations, and also asked respondents which presidential candidate they liked best. (See the bottom of this essay for the exact items we used.) When we analyzed the data, we found that the 2016 presidential candidates have indeed attracted unique voter constituencies with distinct sets of moral priorities. As we shall see, these moral differences among supporters map on pretty closely to real policy debates among the candidates.

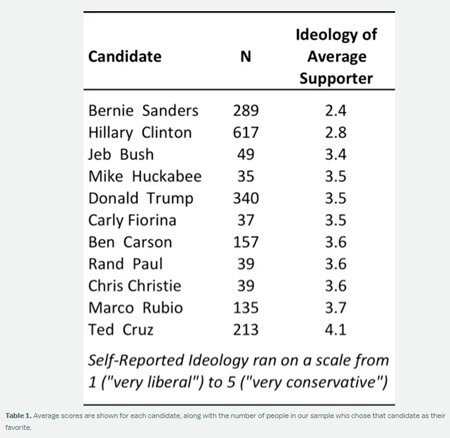

To analyze the data, we first ordered the candidates from left to right based on their supporters' self-described political ideology. The scale ran from 1 ("very liberal") to 5 ("very conservative"). We included candidates who had at least 35 respondents in the survey, although we leave out supporters of Carly Fiorina and Chris Christie in subsequent figures and analyses because their supporters' moral profiles were similar to those of Marco Rubio supporters. (Please see our supplemental blog post for many more graphs and analyses, including those for Fiorina and Christie supporters).

How do the candidates compare?

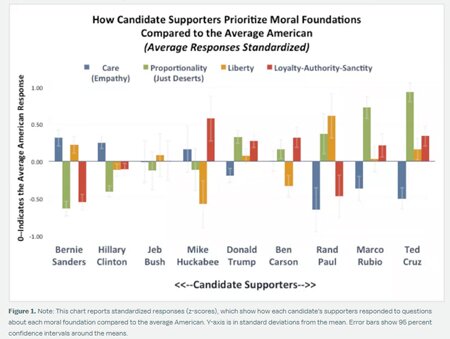

Next, we looked at how each candidate's supporters prioritize each of the moral foundations compared with the average American (Figure 1). Bars above zero indicate that the candidate's supporters place more emphasis on that particular moral foundation compared with the average voter. Bars that dip down below zero do not mean those supporters do not care about the moral concern, only that they gave relatively lower ratings to it compared with the rest of our nationally representative survey sample.

Let's walk through the graph, one set of bars at a time.

1) Care (blue bars): The care foundation measures the psychological tendency to believe that morality requires caring for and protecting the vulnerable. A sample survey item asks respondents if they agree that "compassion for those who are suffering is the most crucial virtue." Individuals who score high on this foundation tend to support a more activist government with a more generous safety net.

- The most obvious thing to note is that supporters of the two Democratic candidates are high, whereas supporters of most Republicans are low. This is consistent with most studies of the left-right dimension: The left values care and compassion as public or political values more than the right does. (We note that all people, and all groups, value care to some extent; we are merely looking at relative differences among groups.)

- Rand Paul's supporters score particularly low. We have consistently found that libertarians score lower on care and compassion compared with others — indeed, they score low on almost all emotions, while scoring the highest on measures of reason, rationality, and intelligence.

- The Republican candidates who put forth a gentle Christian persona draw the most care-oriented Republican voters. Mike Huckabee, Ben Carson, and Jeb Bush supporters are the only Republican groups that are above the national mean or right at it (hence the blue bars don't show for Bush and Carson).

2) Fairness as proportionality (green bars):Proportionality is the desire for people to reap what they sow — for good deeds to be rewarded and bad deeds punished. A sample survey item asks respondents if they agree that "people who produce more should be rewarded more than those who just tried hard."

In practice, a strong desire for proportionality is highly predictive of a preference for small government and a dislike of activist government and the welfare state. (We only asked about fairness as proportionality in our survey, not fairness as equality — which is always higher on the left.)

- The green bars show a very high correlation with ideology: As you move to the right, the bars rise. Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio supporters score highest on this foundation. This pattern is consistent with these candidates receiving the most support from the Tea Party. In our earlier research, we have each independently reached the conclusion that Tea Party supporters are highly motivated by the sense that the government routinely violates proportional fairness, by bailing out well-connected corporations and by spreading a safety net of welfare benefits under people they see as undeserving of help.

- Supporters of Democrats score the lowest on this foundation, particularly supporters of Bernie Sanders. This is consistent with Sanders's emphasis on income redistribution, which many on the right see as a direct violation of proportional fairness carried out in the name of achieving equality of outcome.

3) Liberty (orange bars): The liberty foundation measures the psychological tendency to resist being controlled or dominated. A sample survey item asks respondents if they agree that "everyone should be free to do as they choose, so long as they don't infringe on upon the freedom of others."

- Not surprisingly, Rand Paul's supporters rate this the most important foundation, by far. Although Paul has said he's a constitutional conservative, not a libertarian, his supporters reflect the moral profile of libertarians.

- More surprisingly, Bernie Sanders supporters also score high. Sanders seems to be drawing the more libertarian elements of the left, consistent with his more libertarian views on personal freedom, gun rights, and dovish foreign policy. Libertarian-minded voters seem to choose Sanders if they are on the left on economic policy, and Paul if they are on the right.

- Clinton supporters, in contrast to Sanders's supporters, score slightly below the national mean. This may be one of the most important differences between the two candidates: Clinton attracts voters less concerned about individual autonomy. For instance, Clinton opposes legalizing recreational marijuana and until recently opposed legalizing same-sex marriage, while Sanders supports legalizing marijuana and voted against DOMA back in 1996 when President Bill Clinton signed it into law.

- The most outwardly Christian candidates — Huckabee and Carson — draw supporters who score low on the liberty foundation. This may reflect the fact that socially conservative religious voters tend to prioritize values of community and group cohesion over individual autonomy.

- Notably, despite the frequent use of rhetoric about "liberty" on the right, only a few Republican candidates — Rand Paul and Ted Cruz — attract supporters that score much above average on this foundation. These results suggest that the Cruz campaign strategy to capture libertarian-leaning voters may be working.

4) Authority/loyalty/sanctity (red bars): For simplicity, we took the average of each respondent's answers to all six questions for these three foundations, because they tend to go together as the foundations of social conservatism, and in this data set they generally tell the same story about each candidate. (See our supplemental blog post for graphs and extended analyses of each foundation separately.) Authority shows up in political life in strong support for the police and a "tough on crime" attitude; a sample question in our survey asked respondents whether it is relevant to moral judgment that "an action caused chaos or disorder." Loyalty shows up in political life in strong patriotism and a desire to protect the flag; a survey item we used asked if it was relevant to morality that a person "showed a lack of loyalty." Sanctity shows up in political life in culture war debates related to sexuality (including same-sex marriage) and also to the sanctity of life (including abortion). An item we used asked if respondents agreed that "some acts are wrong on the grounds that they are unnatural."

- Supporters of the Republican candidates tend to highly rate authority/loyalty/sanctity. Supporters of Democrats and libertarian-leaning Rand Paul do not.

- Huckabee supporters most clearly show the classic social conservative pattern — they have high scores on all three of these foundations, as do supporters of Cruz, Carson, and Trump.

- Sanders supporters score the lowest on these foundations and are joined not by Clinton supporters but by Paul supporters. Voters inclined to libertarianism tend to shun restrictions on individual action dictated by valuing authority/loyalty/sanctity.

- Clinton supporters are more socially conservative than are Sanders supporters (although they are still slightly below the national mean on these foundations).

Moral Foundations Theory gives us a clearer picture of what voters care about

What do moral foundations add to our understanding of voter preferences? If you already know a person's age, sex, education level, income, race, and self-reported ideology (liberal to conservative), you can make an educated guess about which candidate he or she is most likely to support. But if you add on top of all that the person's responses to our Moral Foundations questions, does that improve your ability to predict his or her vote?

To find out, we conducted a very stringent test: We performed a series of regression analyses, one for each candidate. (We carried out LOGIT regressions separately for the Democratic candidates among Democratic respondents and Republican candidates among Republican respondents). Then we examined how well each of the moral foundations predicted the likelihood that any particular person would pick each candidate as his or her favorite, while also accounting for the effects of demographic and political variables as well as the other moral foundations.

We wanted to see if adding the moral foundations improved prediction above and beyond the demographic factors that are usually used.

It did.

Table 2 shows what we found. Each row shows which moral foundations were statistically significant predictors of vote choice in the regression analysis for each candidate. The numbers in parentheses show the size of the "standardized beta weight," which quantifies how big the contribution was. Negative numbers mean that the predictor worked in the reverse direction (e.g., scoring low on care makes a Republican more likely to vote for Trump, holding everything else constant).

Among Republicans, four moral patterns stand out. First: Voters who still score high on authority/loyalty/sanctity and low on care — even after accounting for all the demographic variables — are significantly more likely to vote for Donald Trump. These are the true authoritarians — they value obedience while scoring low on compassion. They are different from Huckabee supporters, who appeared to score even higher than Trump supporters on authority/loyalty/sanctity, but also scored high on care, as we saw in Figure 1.

Authoritarianism is often assessed in social science research by asking people two or three questions about the relative importance of teaching their children obedience and respect, but our data shows a limitation of this approach: Not everyone who wants their kids to be obedient is an authoritarian. Some past research has been too quick to lump in social conservatives with authoritarians. MFT offers a more nuanced assessment of voters' moral concerns.

The second pattern picks up the voters who seem to be most concerned about proportional fairness. They want society to reward people according to what they have earned, not according to their needs. These voters are split between Cruz and Rubio. The fact that our proportionality items predicted support for these candidates even after taking background and ideology into consideration shows how directly these candidates are appealing to the core moral concerns of the Tea Party.

But it revealed something else: Despite often being portrayed as opposites (Rubio is "establishment"; Cruz isn't), and Cruz being seen as more aligned with Donald Trump, Rubio and Cruz actually draw from voters with a similar moral profile. Each would probably be doing better in the polls if the other weren't in the race.

The third moral pattern we tracked was Republicans who were not strongly focused on enforcing proportional fairness in society. A low score on the proportionality questions predicted support for Bush (and, we would guess, for Kasich, although we did not have enough Kasich supporters in our data to test that hypothesis).

The fourth moral pattern was the classic libertarian archetype: high on liberty, low on the social conservative virtues of authority/loyalty/sanctity. Those voters gravitate to Rand Paul. Now that Paul has dropped out of the race, the moral profile of his supporters suggest they may find a new home with Cruz, Rubio, or even Sanders, who draws civil libertarians.

Now turning to the Democratic primary: Before controlling for demographic factors, the liberty foundation positively predicts a vote for Sanders and a vote against Clinton. But this effect seems to be driven by young libertarians. Once age is included in the analysis, the liberty foundation no longer adds significantly to the prediction of support for Sanders. When accounting for demographics, Sanders support is actually predicted by low proportionality and low authority/loyalty/sanctity.

Meanwhile, Moral Foundations do not significantly predict a vote for Hillary Clinton; demographic variables seem to be all you need to predict her support (being female, nonwhite, and higher-income are all good predictors).

Much of this contradicts conventional wisdom about the candidates

The 2016 presidential campaign is among the most unusual and confusing in many years, but moral psychology can help us make sense of what is going on. Moral values matter a great deal in both parties. Despite the fact that the Moral Foundations questions don't ask about public policy, they still uncovered distinct moral profiles of each candidate's supporters that map onto actual policy differences that we hear coming from the candidates.

The Democratic candidates are both competing to show how much they care about the poor and vulnerable. It makes sense that they would both covet this impression: There is no difference between their supporters on the care foundation. But beyond care, Clinton and Sanders appeal to different moral values.

Like Barack Obama in 2008, Bernie Sanders draws young liberal voters who have a strong desire for individual autonomy and place less value on social conformity and tradition. This likely leads them to appreciate Sanders's libertarian streak and non-interventionist foreign policy. Once again, Hillary Clinton finds herself attracting more conservative Democratic voters who respect her tougher style, moderated positions, and more hawkish stance on foreign policy.

On the Republican side, we see evidence that the "Reagan coalition" has fractured. No candidate has yet brought together the conservatives, libertarians, and foreign policy hawks. Our survey was conducted last November, but today it is clear that the leading candidates are striving to outdo one another on appealing to social conservative policies (particularly immigration) and hawkish foreign policy (including "carpet-bombing" our enemies).

Despite Trump's longevity in the polls, authoritarianism is clearly not the only dynamic going on in the Republican race. In fact, the greatest differences by far in the simple foundation scores are on proportionality.

Cruz and Rubio draw the extreme proportionalists — the Republicans who think it's important to "let unsuccessful people fail and suffer the consequences," as one of our questions put it. Bush and Huckabee attract those who are not so focused on enforcing proportional fairness. Trump and Paul fall in between on this dimension.

One surprise in our data was that Trump supporters were not extreme on any of the foundations. This means that Trump supporters are more centrist than is commonly realized; consequently, Trump's prospects in the general election may be better than many pundits have thought. Cruz meanwhile, with a further-right moral profile, may have more difficulty attracting centrist Democrats and independents than would Trump.

One last interesting finding: Jeb Bush supporters are closest to the average American voter, despite the fact that his campaign has thus far has failed to gain any traction among Republican primary voters.

Bush's failures may have more to do with his poor debate performances than with his moral profile, but in this time of high and rising polarization, cross-partisan hostility, and anger at elites and the establishment, Bush appears to be suffering from an excess of agreeability: He has no standout moral message that connects to any particular moral foundation, even at the risk of alienating supporters of another.

Politics is in many ways like religion: Voters reward candidates who are effective preachers for a set of moral concerns. Candidates who understand this realize that electoral campaigns are not won just by articulating the most effective policy responses to the pressing issues of our time — they are not even won by appealing to self-interest.

Rather, an effective political preacher offers a clear moral vision of America. That vision includes a historical narrative about where we went wrong, and then tells us how we can set things right. It also includes strong moral arguments that connect with and validate the moral judgments of voters.

So the next time you hear someone ask, "How on Earth can anyone vote for that ... person?" tell them to think about all six foundations of morality.