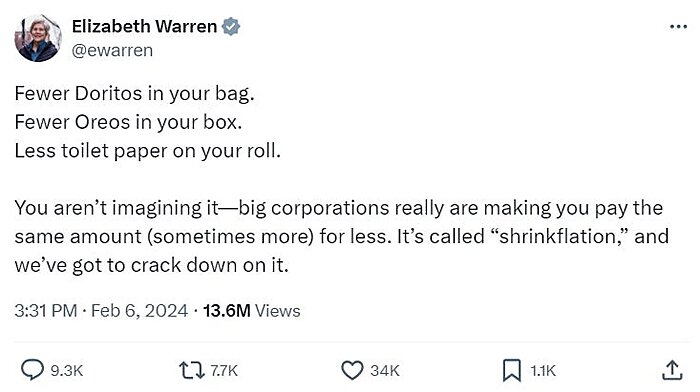

Where Elizabeth Warren leads, Joe Biden follows. I recently wrote here about how Warren has been pushing the “greedflation” narrative that business profit-puffing is causing prices to remain elevated, when she thinks they should be falling. Her latest argument is that businesses have been shrinking product sizes as a crafty way of raising prices.

Before the Super Bowl, Biden jumped on this bandwagon, releasing a video complaining that consumers are now getting fewer chips in their bag, smaller sports drinks, and tinier cartons of ice cream for the same prices. This “shrinkflation,” he said, has got to stop. Lest you think the President was going rogue, National Economic Council Director Lael Brainard was quoted by CNBC contrasting shrinkflation for branded snacks with eggs and milk prices falling. The not-so-subtle implication being that, absent this nefarious shrinkflation behavior, snacks would be falling in price too.

Shrinkflation definitely happened across a range of food and home products (mainly in 2022, see Update below). It refers to firms reducing product or portion sizes while keeping package prices the same, raising the per unit price of the food, drink, or product. But this itself was just a manifestation *of* an inflation that ultimately had macroeconomic roots. In fact, Biden should (by all rights) be grateful that it happened.

Inflation is a rise in the general level of prices, caused by too much money (i.e. excess stimulus) chasing too few goods. A period of inflation doesn’t mean that every price is going up, or going up by the same amount, because supply and demand changes alter relative prices too. In fact, because we can’t observe inflation directly, we must estimate it using a weighted average of prices that consumers spend money on. There may be all sorts of reasons why the relative price of eggs or milk has fallen within that average. But, across the economy as a whole, positive inflation just means a rise in the general level of prices paid by consumers.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) tries to track changes in product size and quantity when calculating this change in the general level of prices so that it accurately reflects inflation. When a product in the CPI basket decreases in size but keeps the same price, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) considers this a price increase because the consumer is getting less for the same amount of money. This adjustment aims to ensure that the CPI reflects the weighted average not of observable sticker price changes but the actual per unit price the customer faces.

In reality, tracking and adjusting for shrinkflation can be complex, as it requires constant monitoring of product changes in the market and changing weights of consumer spending baskets. While the BLS makes efforts to account for these changes, it may not capture all instances of shrinkflation, potentially underestimating the true inflation rate experienced by consumers.

So why do I say Biden should be grateful for shrinkflation?

If the CPI isn’t accurately capturing shrinkflation, then the real story here is: “measured inflation has been somewhat underestimated — inflation has been worse than has been widely reported during Biden’s time as President!” This doesn’t seem like a message Biden would want to propagate, particularly in an election year.

If, on the other hand, inflation has been measured correctly, Biden’s critique implies he’d have preferred all businesses to overtly raise package prices rather than shrink their size. Not only does this presume he knows better than the businesses how best to deal with an inflationary environment (including consumers’ sensitivity to price changes), it would almost certainly have made food price inflation even more salient with consumers than it already has been. Again, not great for Biden’s popularity or re-election prospects.

Sure, a lot of consumers still notice and are concerned about shrinkflation. But some won’t have noticed subtle changes to product sizes to the extent they would have noticed rising package prices. Biden is thus likely to have benefited politically to the extent businesses opted for this inflation response.

Of course, Biden and Warren Democrats are bringing attention to “shrinkflation” now because the 21 percent increase in the level of food prices since 2021 remains a big political problem for them. They are hoping that the public won’t perceive shrinkflation as just a form of inflation. Instead, as with “greedflation,” they hope this narrative will just help shift the blame for cost of living pressures onto rapacious businesses. And you can’t blame them politically: they and several heterodox economists have already been pretty successful in convincing much of the public that greedy companies can just decide to increase prices.

This, of course, ignores that businesses are disciplined in what they can charge by competition (and the snack industry is pretty competitive — if one firm tried “shrinkflation” purely to raise profits, other companies could undercut them). And, of course, it forgets that firms are limited in what they can charge by customers’ willingness and ability to pay (where did they get all that extra money to pay higher prices, I wonder?)

But when did such pesky economic logic matter? Shrinkflation is just the latest attempt to point the finger at corporates for symptoms of macroeconomic policy failures. The irony is that, without shrinkflation, the political heat on Biden for high grocery bills would be even more intense.

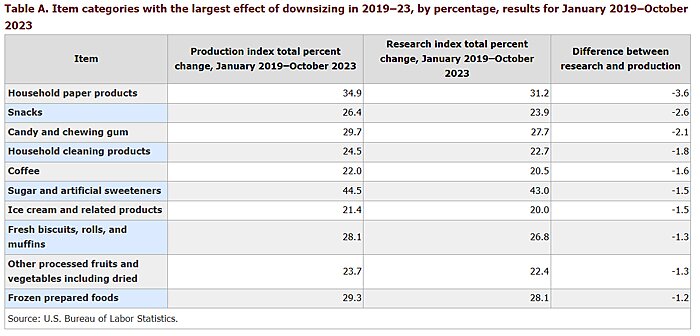

Update: Cyril Morong on Twitter points out a nice article by the BLS on how they attempt to deal with shrinkflation. In “normal times” they estimate that the net effect of upsizing and downsizing on the overall price level is marginal — “product size changes (upsizing and downsizing) increased the CPI all commodity and services index by 0.01 percent per year.” But for individual products the effect can still be substantial.

The Table below shows the goods for which the effect of downsizing on the index was largest from 2019 through 2023. The “Production index” column is the CPI price change taking account of downsizing; the “Research index” value ignores downsizing. As you can see, prices rose significantly higher for household paper products, snacks, and the other foods listed once we account for shrinkflation. This confirms my point in the piece above: the decision for companies to reduce product sizes is likely to have made food price inflation less salient and been of political benefit to the President.