If there is only one thing people know about Donald Trump, they know he wants to build a border wall. And if there’s only one thing people know about Democratic lawmakers, it’s that they rarely turn down multibillion-dollar infrastructure projects.

Yet since December 22, the federal government has been partially shut down after President Trump and Democratic congressional leaders were unable to compromise on $5.7 billion in funding for a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) has called the border wall “immoral, ineffective, and expensive,” and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) said it was “wasteful” and “doesn’t solve the problem.” Democratic leadership may feel confident holding their ground against Trump during the shutdown in part because public opinion is on their side.

Averaging national public opinion polls conducted in 2018 reveals that 6 in 10 Americans oppose building a border wall. For instance, a CBS News poll conducted in October 2018 found that 60 percent oppose “building a wall along the US-Mexico border to try and stop illegal immigration,” while 37 percent favor building a wall.

Americans Used to Support a Border Wall

But just a few years ago a majority of Americans supported building a border wall or fence. In 2013, an ABC News/Washington Post survey found that nearly two-thirds (65 percent) of Americans supported building a 700-mile fence along the border with Mexico and adding 20,000 border patrol agents.

The same survey found a slim majority (52 percent) still favored building a wall even when told it would cost $46 billion—much higher than Trump’s current request. Similarly in 2011, a majority (57 percent) supported building a security fence, even without additional patrol personal, a Quinnipiac poll found.

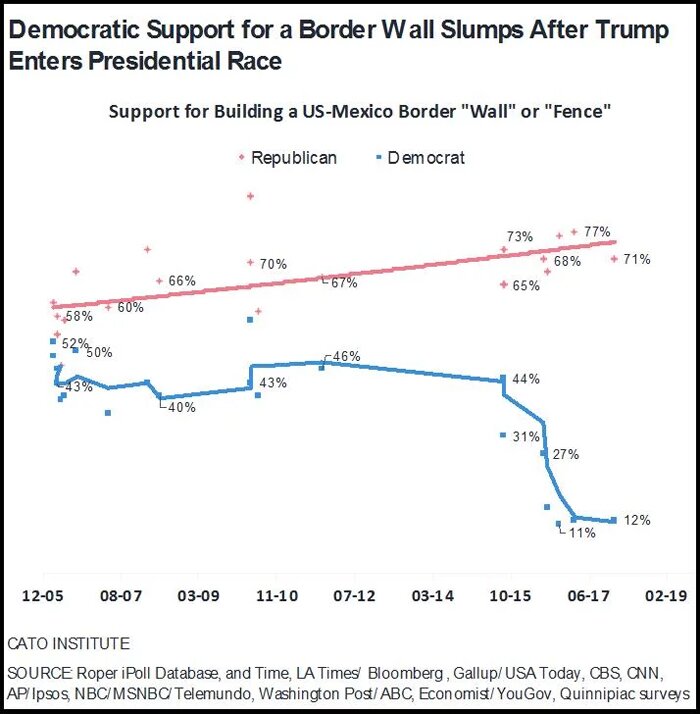

Not only that, but in early 2006 a Time/SRBI poll found that a slim majority (52 percent) of Democrats also favored “building a security fence along the 2,000-mile US-Mexican border.” Sixty-one percent (61 percent) of Republicans also agreed. Between 2005 and 2015, polls show that nearly half of Democrats continued to support building a border barrier of some kind.

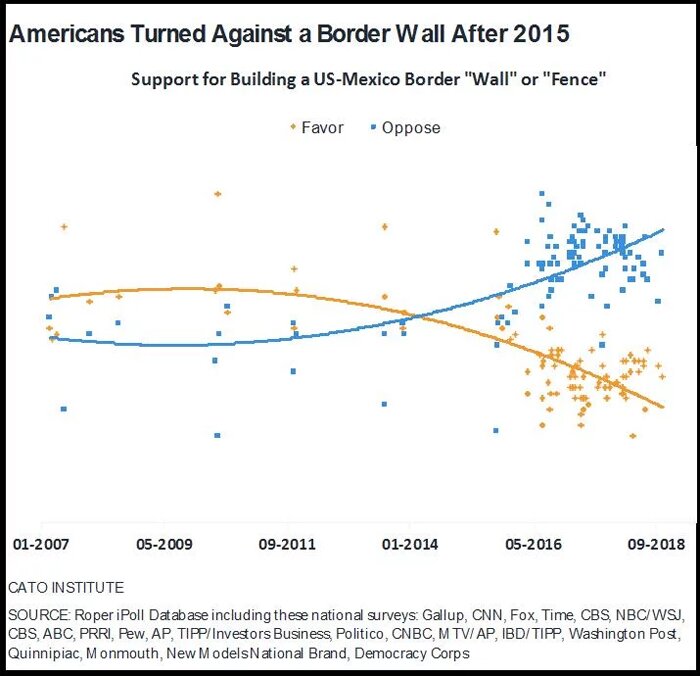

However, things changed in 2015 when Donald Trump announced his bid for the presidency. Since then opposition rose upwards among the general public. Analyzing more than 150 polls conducted between 2007 and 2018 from the Roper Center iPoll Databank reveals that an average of 43 percent of Americans opposed building a border wall between 2007-2014. Opposition increased to 48 percent in 2015, 58 percent in 2016, and 61 percent in 2017, and then back to 59 percent in 2018.

Democratic support shifted more swiftly starting in the fall of 2015 onward. Now only about 12 percent of Democrats support a border wall or fence. As the charts above demonstrate, Trump's entry into politics (and making immigration issues salient) played a major role in turning the public against the border wall.

Why Did Americans Change Their Minds About the Wall?

Here I offer four reasons that may explain why Americans turned against building a border wall.

1) Harsh Rhetoric Makes People More Sympathetic to Immigrants

First, Americans may become more sympathetic of immigration when public figures who want to reduce it, like Trump, Steve Bannon, or Pat Buchanan, are on the offensive. Rhetoric from all sides becomes emotional, the media weighs in, people make statements that give the impression they do not like immigrants, and voters get upset.

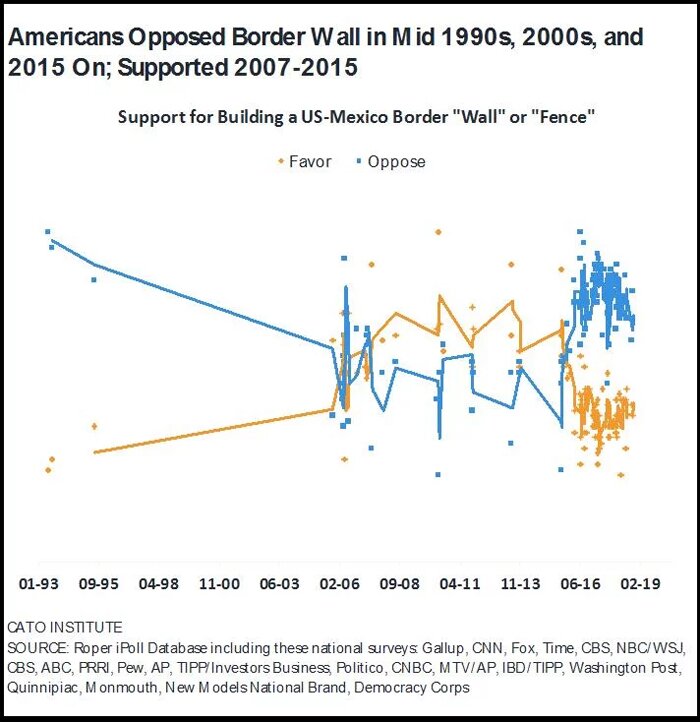

Available survey data reveals two such instances, first in the mid-1990s and next in the mid-2000s. Both were periods when the nation debated immigration reform, with skeptics leading the charge.

In the mid-1990s, immigration became a hotly contested issue with California’s Prop 187, which sought to restrict unauthorized immigrants’ access to social services, and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigration Responsibility Act President Clinton signed in 1996. Debate during this time centered on expanding border security, cutting legal immigration, and preventing unauthorized immigrant children from accessing public schools.

Emotions ran hot. For instance, in a televised interview in 1991 Buchanan argued “there is nothing wrong with us sitting down and arguing that issue that we are a European country” and in 1995 he described illegal immigration as a “foreign invasion.”

Gallup surveys conducted in 1993 and 1995 found about two-thirds of Americans opposed a border wall or fence at that time. However, by the mid-2000s, support for a border wall bounced back. A Time survey conducted in early 2006 found 56 percent supported building a 2,000-mile security fence.

Polls reveal another period where the nation intensely debated immigration and support for a border wall plummeted. Starting in the spring of 2006, majorities once again came to oppose a wall. For instance, a Gallup survey found 56 percent opposed a border barrier by May 2006, just a few months after the Time survey. This was precisely the time Congress debated immigration reform, particularly in relation to H.R. 4337, which sought to build a 700-mile border fence and classify unauthorized foreign citizens and those who provide them assistance as felons.

To give a taste of the rhetoric of the time, Buchanan lamented in his book “State of Emergency: The Third World Invasion and Conquest of America,” that white people would become the minority by 2050 and that by then “America will be a Third World country.”

One could see how many people were offended. Unauthorized foreign citizens and their supporters organized mass protests across the country, “A day without an immigrant,” to demonstrate what the economy would be like without their contributions.

But once the debate subsided, support for the border wall bounced back and majorities supported it again. That is, until Trump entered the presidential race and made the border wall a centerpiece of his policy agenda.

Like in the mid-1990s and 2000s, the public today has turned against building a border wall. The more immigration restrictionists push for building a border wall, the more impassioned the rhetoric, and the more salient it becomes in the news, the more people get offended, and voters turn against it.

2) People Feel Differently About a ‘Wall’ than a ‘Fence’

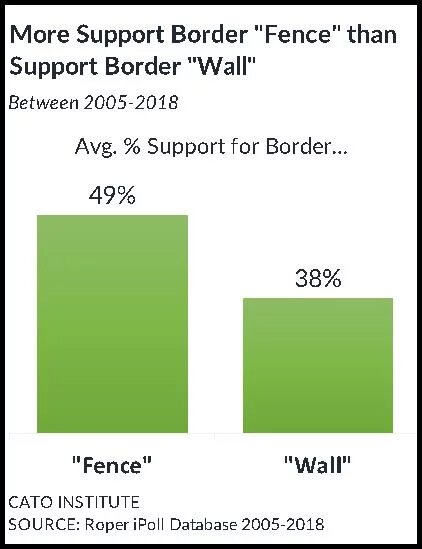

Second, some people make a distinction between building a border “wall” and a border “fence.” Indeed, analyzing 150-plus polls conducted over the past 13 years available in the iPoll Databank archive shows that 49 percent supported a border “fence” while 38 percent supported a border “wall”—an 11-point difference. However, Trump has emphasized building a wall rather than a fence, whereas lawmakers in the past largely discussed erecting fences.

Why do people make the distinction between a fence and a wall? People may simply think a wall means no one can cross it and thus it would completely halt all immigration across the Southern border.

Furthermore, people may perceive nefarious motives from people who wish to build a border “wall” rather than a “fence.” You might not care much if your neighbor built a fence between your house and theirs. But what would you think if your neighbor erected a large, tall, thick concrete wall between your house and theirs? You might think they don’t like you or want to interact with you. You probably wouldn’t be inviting them over for dinner any time soon either.

Walls give the impression of exclusion and that they cannot be crossed, even legally. Fences, on the other hand, often have gates and give the impression that they can be crossed using the proper channels.

Many supporters of building a border wall may think that a wall can also be crossed if done legally. However, in the minds of the median voter, a wall may sound permanent and impermeable. For some voters this is a feature, but for others it’s a bug.

This conception of what a wall means is demonstrated through a very poorly written survey question from pollsters Greenberg Quinlan and Rosner Research, when they asked voters if they favored or opposed: “Building a fence along the Mexican border to keep Mexicans from entering the country.” No serious Republican lawmakers are calling for a wall to prevent all Mexicans from immigrating to the United States. The fact that these pollsters misinterpreted the intentions of the wall show that many Americans believe the wall is motivated by animus toward Hispanic migrants and their descendants.

3) The Border Wall Has Become a Symbol

This leads to the third likely reason for the recent shift against building a border wall: In the minds of many Americans—although not all—the wall has become symbolic of attitudes toward immigrants and racial minorities. As political scientists may put it, the wall has become “racialized.”

Particularly Democrats have come to believe that support for a border wall indicates animus toward immigrants and people of color more generally. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s contention that the border wall is “immoral,” not just cost-ineffective, demonstrates that for many the wall is about values, not number-crunching.

This clearly wasn’t the case several years ago when majorities of Americans, as well as Democrats, supported erecting a border wall or fence. How did framing of the border wall shift from being about security to being about race?

When Trump announced his bid for the presidency, he declared Mexico is “sending people that have lots of problems…They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”

Many people interpreted Trump’s remarks to mean that he thinks a majority of immigrants from Mexico are criminals while the minority, or only “some,” are law-abiding. This led many to conclude that Trump’s motivation for building a border wall was driven by animus toward a majority of Mexican and Latino immigrants.

Trump further fueled this impression when he claimed that the “Mexican heritage” of the judge presiding over Trump University lawsuits was incapable of impartiality because of his Mexican heritage. Even if Trump didn’t mean to give this impression, it’s understandable how millions concluded that a dislike of Mexican immigrants—here legally or otherwise—motivated Trump’s promise of a border wall.

Surveys show that many Americans reacted negatively to Trump’s comments. An NBC/WSJ poll conducted soon after Trump’s presidential campaign announcement found 37 percent thought his comments were “insulting” and “racist.” Even in 2018, a Quinnipiac poll found that 41 percent believe the “main motive behind President Trump’s immigration policies” is “racist beliefs.”

To be clear, many Americans who support the border wall do not view it as exclusionary or symbolic of animus toward immigrants. However, many people did come to view it this way, and that has significantly contributed to the public turning swiftly against it.

Further evidence that the wall has become a symbol is the fact that Hispanics have consistently opposed building a wall or fence along the border with Mexico for at least the past decade, even though most are U.S. citizens born in the United States or are legal residents. In 2008 only 11 percent supported “building a fence along 670 miles of border between the United States and Mexico,” an AP/Ipsos poll found.

This shows that Latino attitudes about the border wall are not about Trump, because this survey was conducted seven years before Trump ran for president. Latino attitudes have persisted, with only 13 percent in support of a wall in 2018, according to a Washington Post/ABC survey. The fact that most Hispanics are U.S.-born citizens yet still oppose the border wall indicates they view it as a symbolic gesture saying they and people like them aren’t wanted.

4) Democrats Will Oppose What Trump Supports

Trump is a polarizing figure, particularly for Democrats. Survey experiments conducted by Reuter/Ipsos found that simply telling Democrats Trump supports a policy turns them against it—even universal health care. For instance, 68 percent of Democrats ordinarily would agree that when it comes to health care “government should take care of everybody and the government should pay for it.” But among another sample of Democrats who were told Trump made that statement, only 47 percent supported government guaranteed health care—a 21-point drop.

Republicans given the same treatment moved only by 6 points. A third (33 percent) of Republicans supported government-guaranteed health care when they were not told that Trump once supported it. But among those who were told Trump made that statement, 39 percent supported it.

Thus, even on an issue as central to the Democratic policy agenda as government-guaranteed universal health subsidies, Trump can turn Democrats against it. So certainly he can turn them against a border wall too.

But one of the reasons Democrats and the media turned against Trump so intensely was because of the language he chose to use to talk about immigrants. Partisanship alone can’t explain why more than just Democrats, but the median voter also turned against a border wall. In a world where Trump had not gone on the offensive to curb both legal and illegal immigration and had not used inconsiderate language in the process, it’s likely that fewer people would oppose him with such zeal.

Democrats Will Resist Compromise

Democrats talk a lot about the benefits of compromise. In fact 75 percent of Democrats in a 2016 VOTER Survey said they’d rather lawmakers “compromise to get things done” rather than stick to principles. Yet Democratic leadership hasn’t shown signs of budging on building a wall, at least for now.

It’s not particularly credible for Democrats to say they oppose the wall because it’s not “cost-effective.” If they opposed it for that reason, why did many support a border barrier just a few years ago? It’s equally cost-ineffective today as it was then.

But Pelosi calling the wall “immoral” is a more credible explanation for why Democrats oppose the wall now but not before. It’s also indicative that she doesn’t view the wall like other public policy disagreements. As Democratic constituents have come to see the border wall as a symbol of animus toward immigrants, they can’t allow leadership to compromise without violating deeply held values.

What All This Might Mean

There are useful lessons here about how Americans changed their minds on the border wall. Facts and numbers about the cost-ineffectiveness of building a 2,000-mile wall across diverse geological terrain were available before 2015 and did not change many minds. Telling people that it costs money the country doesn’t have didn’t work. Explaining that unauthorized immigration will still continue despite a tremendous amount of money spent also hasn’t been particularly persuasive.

Instead, many people changed their minds about a border wall when they came to view it as a symbol of exclusion and animus toward immigrants and racial minorities and thus immoral. While many advocates of the border wall insist the wall is a humanitarian cause and is necessary for border security, they are talking past those who view it as a racialized symbol.

Perhaps there’s something to be learned here. Sometimes persuasion requires more than simply facts and reason. But persuasion needs the flavor of righteousness for people to care enough to change their minds and for it to stick.