December polling from PBS News, NPR, and Marist shows President Trump at his worst approval rating ever on the economy. As I explain in my column for The Times today, the inflation issue that helped win him the election has, remarkably, become his political albatross.

The December Echelon Insights Omnibus survey of Americans explains why. The modal response to a question on the biggest issue facing the country is the “cost of living.” For most, what’s happening with prices has become synonymous with, or at least the best indicator of, the country’s economic health. A majority (56 percent) say that prices falling would be the surest sign of an improving economy. Just shy of three-quarters (74 percent) say that only prices falling would convince them that inflation or the cost of living was no longer a problem.

Here’s where the disappointment with the President seeps in. Among those who voted for President Trump in the 2024 election, 80 percent thought Trump would deliver lower prices. And some individual prices like gas have certainly come down since January. Yet, as they are prone to do given inflation, on average prices have gone up. In fact, inflation—i.e. the rate of increase in prices—trended up through most of the year, albeit with month-to-month volatility. Economists can argue about whether one-off factors or items like shelter are distorting the picture. Yet today’s figures for November show the consumer price index inflation rate down to 2.7 percent over the past year, i.e. still significantly higher than consistent with “at target” inflation.

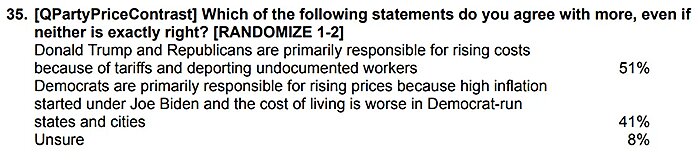

Voters are disappointed with these outcomes. This isn’t the sort of price declines they wanted. And there’s a plausible story that, on the margin, Trump’s policies have made things worse than they needed to be. We can debate the magnitude but, short-run, a major dose of protectionism and deportations is stagflationary—raising the price level by reducing real output. On macroeconomic policy, we’ve seen from Trump yet more borrowing and the threatening of Fed independence, including calls for cheap money and demands that the Fed lower government borrowing costs. That at least raises inflation risk. All this perhaps helps explain why a majority of voters now blame Donald Trump and Republicans more for rising costs than Democrats who were in government as inflation peaked.

The public isn’t subtle about the outcomes they want instead. As I told The Free Press recently, real earnings are up this year, so voter angst is not really about “affordability” as traditionally understood. No, voters appear to still be experiencing “sticker price shock” when they get their groceries or pay their gas bills. They can’t believe what they are paying because they remember pre-pandemic prices. What they hanker for is the 2019 price level, when prices were 25–30 percent lower.

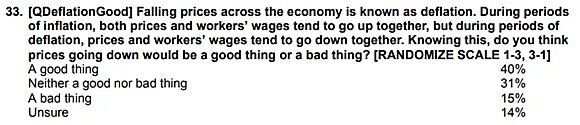

In fact, many are willing to outright endorse deflation to achieve lower prices, even after they’re told deflation means falling nominal wages too.

Taking this answer at face value, meeting the public’s expectations on the cost of living is incredibly difficult, perhaps explaining why the President seems so exasperated. The only way for policy to achieve a sharp decline in the general price level would be to concoct monetary and fiscal policy to crash spending across the economy. Yes, there’s a respectable case for a “price level targeting” whereby periods of above-target inflation from monetary excesses are made up for by a long period of modestly below-target inflation. Yet if voters want sharp nominal price cuts *now*, that would require very contractionary policy that risks a deep, painful recession.

Nonetheless, voters have historically said they want to see governments reverse excess inflation quickly. Jason Furman reminds us that in Robert Shiller’s classic 1997 chapter “Why do People Dislike Inflation?” 68 percent of the public agreed that governments should try to reverse a 20 percent price-level overshoot. Nearly all economists (92 percent) disagreed.

If policymakers won’t use macroeconomic tools to deliver what voters want because it’s too dangerous, but voters still demand lower prices, then we’ll see microeconomic policy fiddling in product markets. Progressives offer interventionism: price controls, subsidies, monopoly busting and greater government involvement in pricing and product formulation in general. That’s proved popular in recent New York City and New Jersey races, but of course, it was macroeconomic excess that caused inflation in the first place. To a first approximation: fiddling with relative prices can’t change the overall price level. At best, these strategies only shift certain high prices paid onto taxpayers, and at worst they push prices even higher or cause shortages, black markets, misallocation, and lower quality goods.

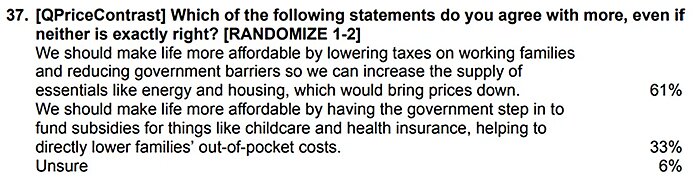

Interestingly, although it didn’t test all of these ideas, the Echelon Insights poll offers one heartening result here. Offered two different strategies of micro interventions to making life more affordable, only 33 percent backed the progressive approach of extending subsidies for services like childcare and health insurance to reduce out-of-pocket costs. Most voters know, in other words, that robbing Peter to pay Paul doesn’t make stuff inherently cheaper. A large 61 percent instead said they preferred lowering taxes and removing government barriers to expand supply of essentials like housing and energy as a way to reduce prices.

As I argued this week in Reason, although this is a more contentious and slower way of offering relief, removing government-imposed barriers to supply is the only strategy that would sustainably lower the relative prices of those core goods and services people care most about. Tariffs and other protectionist mandates quietly raise consumer prices, input costs, and inefficiency. Land-use, zoning, occupational licensing, endless permitting, and environmental reviews choke off worker, housing, and energy supply by raising costs. All of it raises consumer prices or eliminates cheaper options. So why not use this discontent as the justification to change things?

This week’s polling is a stark warning for the President, but there’s at least this glimmer of hope. Voters want lower prices. But some answers at least suggest that they may be ready to give supply-side reforms a whirl to deliver them.