Dear Capitolisters,

Hang around with people on the right enough (as I do), and you’re sure to come across some variation of the following argument: “I support immigration—legal immigration” or maybe, “Immigrants are great, but they gotta wait in line—just like every other generation of immigrants has.” Illegal immigration, by contrast, is the real problem—one solvable by more border enforcement (walls, government agents). Or, as a certain former president used to say, we should be a nation of high walls and (big, beautiful) doors.

Implicit in this argument, however, is that those doors actually open—that the laws governing immigration into this country are not merely smart and just, but also effective at both processing and admitting new immigrants dutifully waiting to get into the country. New research shows just how wrong those notions are—and that anyone who sincerely thinks immigrants should be welcomed here simply cannot support existing law as it currently stands. Because that law has effectively sealed most of our doors and ensured that, for millions of people, those “lines” never move. And when the lines never move—guess what—those same people look for alternatives, including illegal ones.

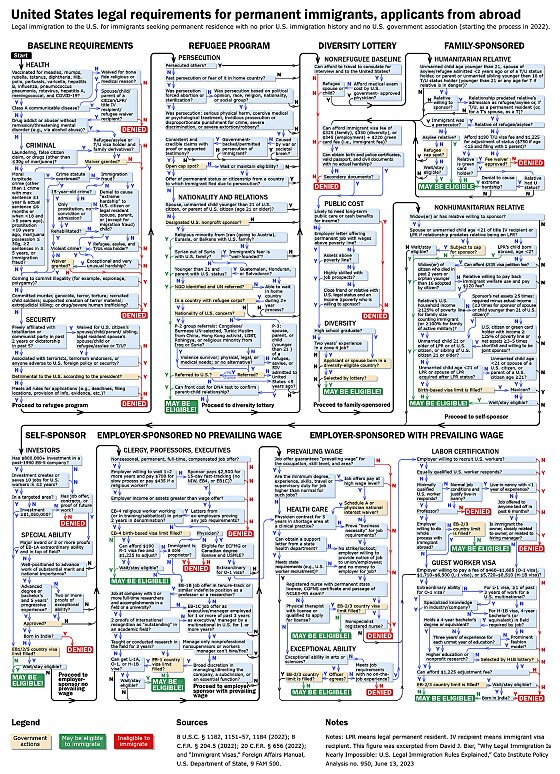

Charting Our Legal Immigration Blockade

To really understand the situation, I recommend you not simply glance at this chart before moving on—take a minute, click the link, zoom in, follow some lines, and really soak it all in. As you’ll hopefully see, almost every path for a hypothetical immigrant is eventually blocked by the law we tell hopeful immigrants to follow.

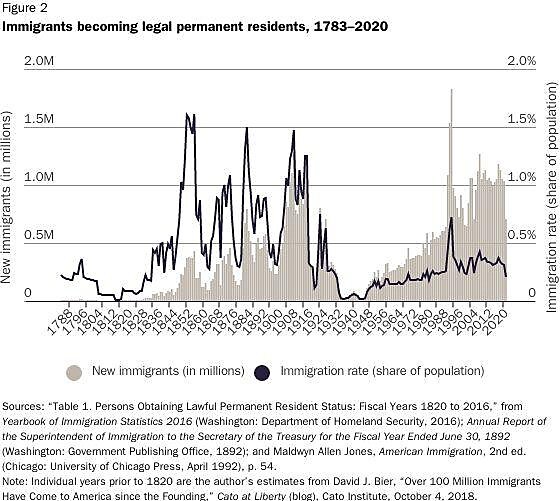

Because of these and other effective restrictions, the flow of legal immigrants into the United States has been reduced over the last century to more of a dripping faucet than some sort of tidal wave. A Bier notes, this is owed in large part to a fundamental shift in U.S. immigration policy (emphasis added):

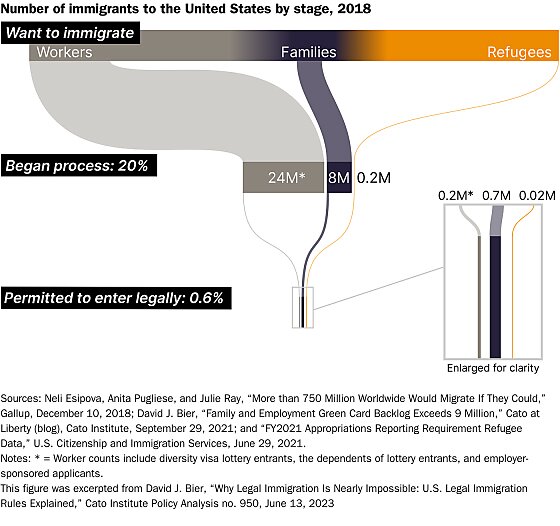

Until the Immigration Act of 1924, everyone in the world was eligible to immigrate to the United States unless the government proved they fell into an ineligible category. In other words, innocent until proven guilty. Since then, the foundational principle of U.S. immigration law is that everyone in the world is ineligible to immigrate unless they prove to the government they fit into an eligible category. The result is that over 99 percent of all those wanting to immigrate to the United States cannot do so legally.

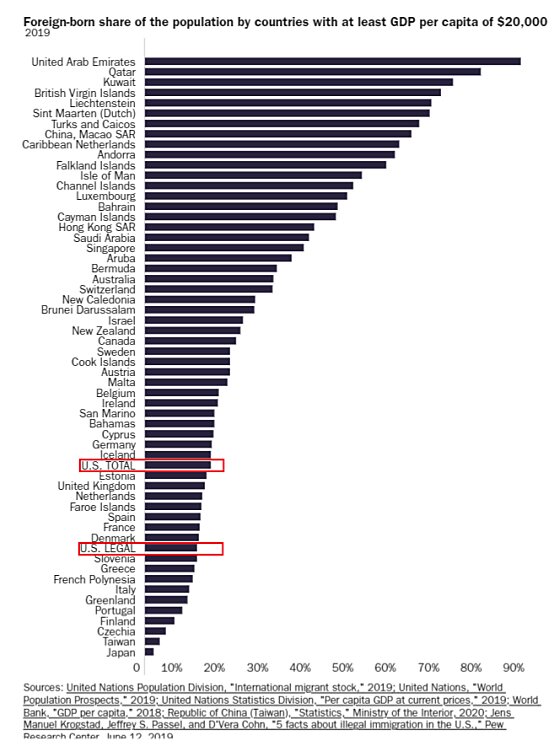

And, while a million immigrants do make it into the country each year, the United States’ sheer size (both landmass and population) means that our lawfully entered foreign-born population is middling among industrialized nations—below not just wealthy islands and petrostates but also plenty of Western democracies like Australia, Switzerland, and Canada—and well below levels seen before the United States switched to a “guilty until innocent” system:

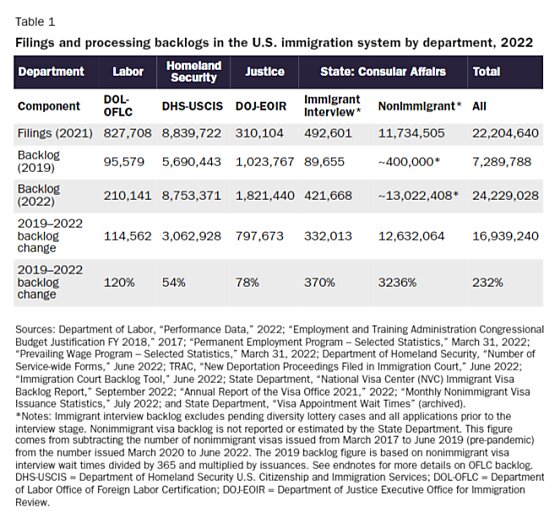

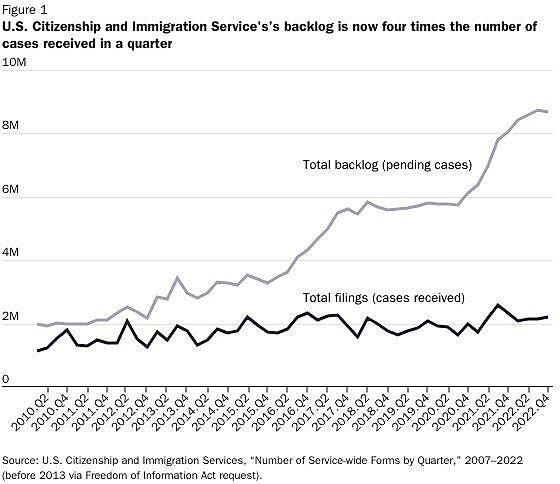

Some of this trickle is by design (more on that in a sec), but a lot of it results from massive processing backlogs—not some sort of congressionally mandated cap on entrants but instead simply where lawful requests for immigration-related benefits exceed the number of processed requests. As Bier shows in a separate paper, backlogs are a pervasive problem and last year exceeded more than 24 million cases across the entire U.S. government:

He also shows that the processing backlog problem has gotten much worse in recent years …

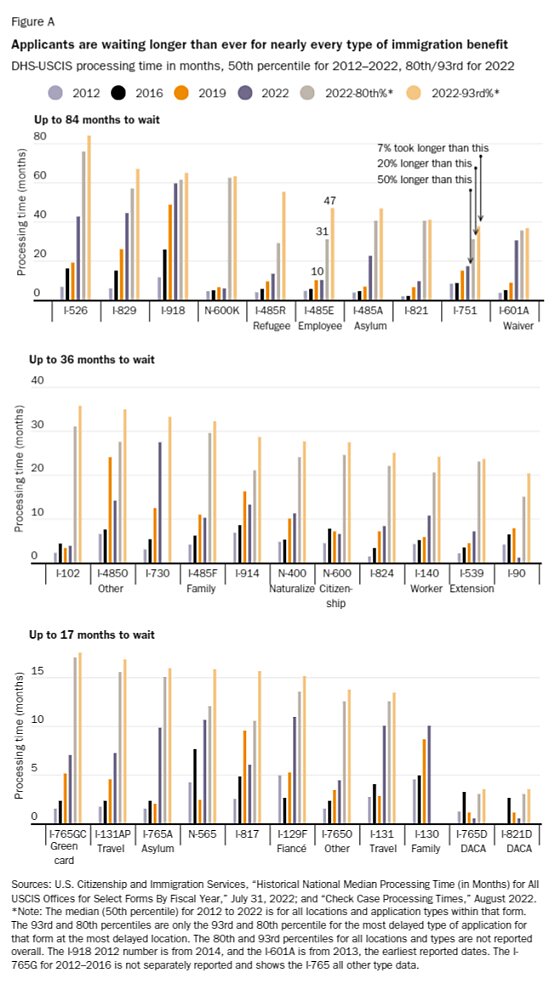

… across basically all visa categories:

These huge administrative backlogs act as a de facto cap on U.S. immigration flows. Even if Congress lifted all the various quotas and conditions for residing in the country tomorrow, Bier explains,

Processing backlogs would effectively nullify its action. If the agencies can administratively process only one million green cards annually, authorizing them to approve nine million would simply move immigrants from a cap‐induced backlog to a processing backlog. It would not solve the problem.

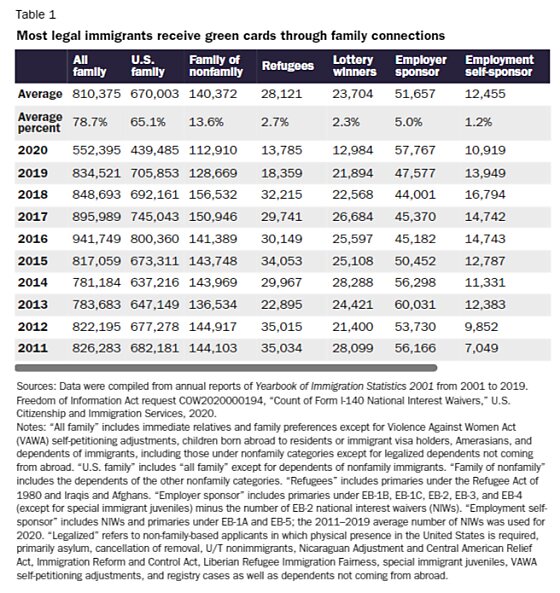

But our legal immigration problem is also a substantive one — not merely limiting the total inflow of applicants but also important types. In his new paper, for example, Bier shows that the vast majority of foreigners admitted into the country are family, while other forms—especially workers—are a small share of total inflows:

Employment “self-sponsor” is a naturally small category: It’s for people who are, in legal terms, “extraordinary,” have work of “national importance,” or can afford to make at least $800,000 in investments in the United States. For any other person seeking to lawfully move to and work in the United States … well, good freaking luck:

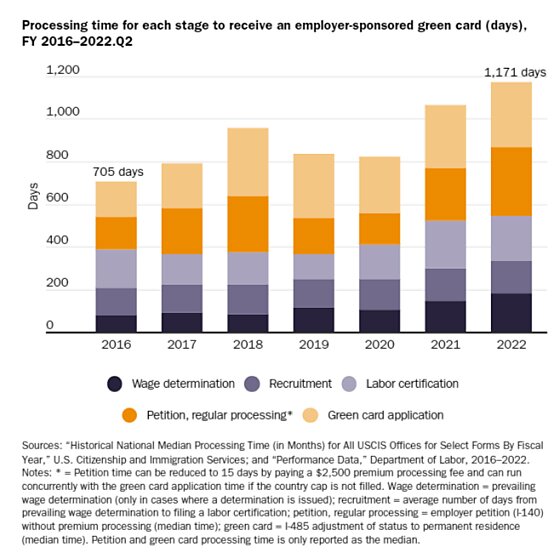

Employer sponsorship is the one chance where, in theory, it should be open to anyone with an employer sponsor in the United States. In practice, the procedures are so backlogged, so costly, and so time‐consuming that very few employers are willing to attempt it except for the highest‐paid workers in America. Aside from a few specific occupations, employers must advertise the job to U.S. workers. The process takes years, and even if no U.S. worker applies, very few employers can afford to keep a job open for such a prolonged period.

Bier shows, in fact, that the whole process for a single immigrant worker took almost 1,200 days to complete in 2022—an increase of almost 500 days since just 2016:

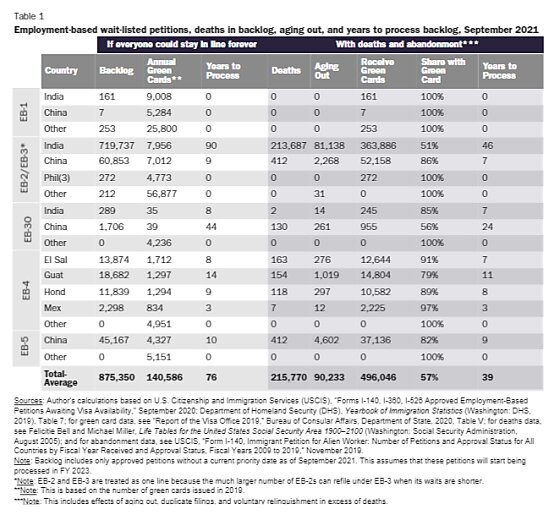

For some applicants, particularly educated Indians, country-based caps make the wait much, much longer:

Indian applicants filing this year (those with a master’s or bachelor’s degree) face a wait of about 90 years.… As Table 1 shows, about 215,000 petitions will expire as a result of the death of the immigrant before the immigrant receives a green card, and more than 99 percent of these deaths will be Indians… Another roughly 90,000 children of employment‐based immigrants will “age out” of eligibility when they turn 21 — because only children under the age of 21 may qualify based on their parents’ application — largely children of Indian applicants.

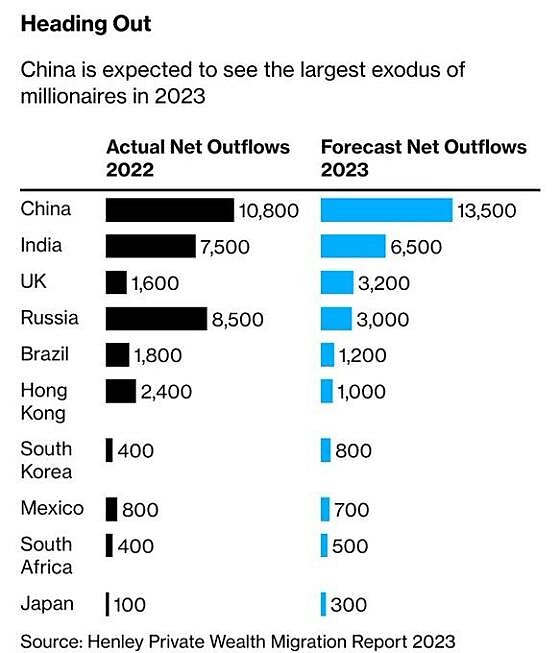

No surprise, then, that many of them—even ones who have lived here for years (temporarily) and started businesses and families while dutifully waiting “in line”—are simply “giving up on their green card dreams” and looking to more welcoming places, like Canada.

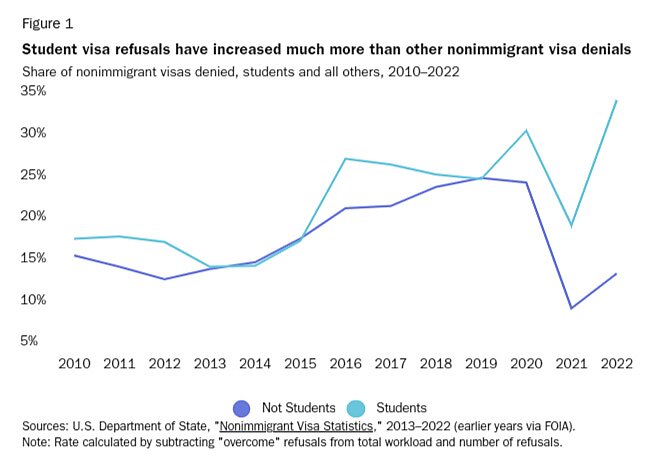

Other no-brainer visa categories reveal similarly ridiculous (and frustrating) restrictions—ones that have also expanded in recent years. I noted a few weeks ago, for example, how other countries are increasingly attracting foreign scientists and students. New research from Bier shows that some of this shift is the United States’ actively turning students away—more than 220,000 of them who had already been accepted into a government-approved university and would have paid more than $6.6 billion in annual U.S. tuition and living expenses.

Other evidence shows that this trend is very likely owed to U.S. consulates’ peculiar—and not in line with the express legal requirements—rules for processing Indian student visa applications. As a result, “India has a much higher than average student visa refusal rate even though Indian students are extremely successful in the United States.”

In sum, U.S. immigration law, as both written and implemented, effectively and arbitrarily bars tens of millions of people from moving here, bettering their lives, and contributing to our economy and society—in most cases, not just for a few months or even a few years, but forever.

The Connection Between Legal and Illegal Immigration

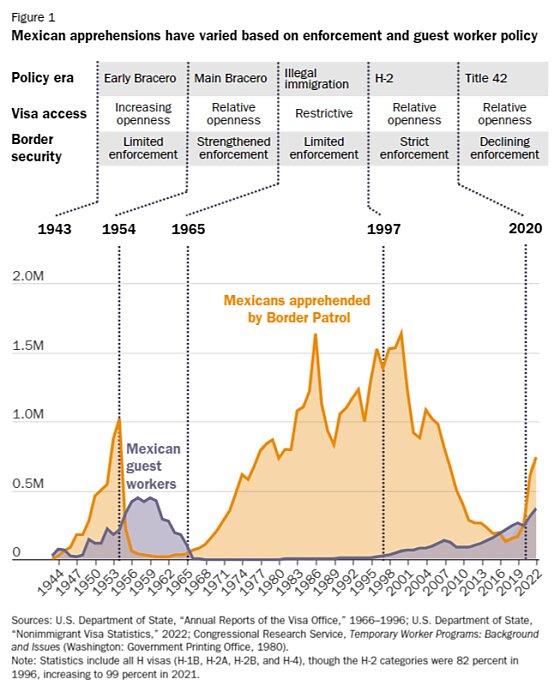

Finally, it’s important to note that this effective blockade on legal immigration has almost certainly made illegal immigration worse by denying migrants an efficient means of living and working in the United States, whether for economic or other reasons. Two examples—one old and one new—show how this works in practice. First, past expansions of Mexican guest worker programs—the “bracero” programs of the 1940s and 1950s and then the H‑2 program of the 1990s-2000s—coincided with significant declines in border crossings and apprehensions, while more restrictive periods saw much the opposite. In short, by driving would-be illegal border crossers into legal visas, the United States got more workers and fewer border problems. By contrast, “caps on visas and limits on the types of jobs that the workers can perform inevitably cause illegal immigration to reappear.”

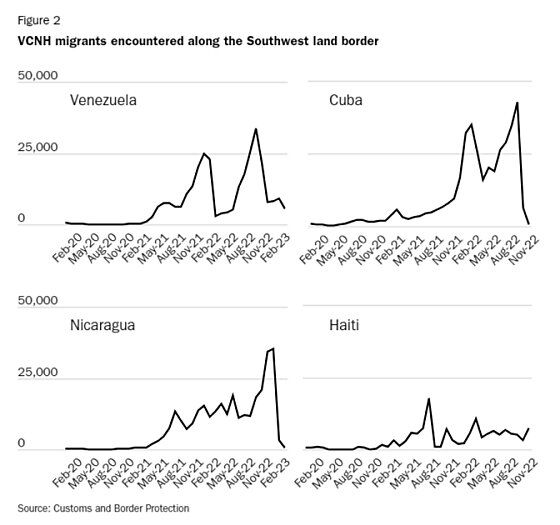

Recent Biden administration policy shows similar things. In January of this year, the United States began allowing up to 30,000 migrants from Venezuela, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Haiti (VCNH) to legally enter the United States each month through humanitarian parole (subject to health and security screenings and other requirements). This policy change coincided with a 39 percent decline in encounters of migrants crossing the southern border with Mexico, and an 84 percent decline among individuals from the targeted countries. Thus, “almost 80 percent of the total decline in encounters along the border from December to February comes from a reduction in VCNH migrants.”

In short, the early data appear to confirm that giving individuals a legal way to come here relatively easily (keyword: relatively) will discourage them from trying to do so illegally, including via the southern border. No, this doesn’t mean that a better immigration system would eliminate all illegal immigration or all problems at the border. But it’d surely help—a lot, and far more than just adding more border agents or employing other forms of deterrence (which, as three decades of bipartisan policy have proven, doesn’t work much at all).

So if you care about illegal immigration, you should really care about how ridiculously bad our legal immigration system currently is and how it fuels the problem you so deeply care about.

Summing It All Up

You don’t have to be for “open borders” (or whatever) to see that there’s a huge problem with America’s immigration system: It’s slow, arbitrary, ineffective, and harmful. Not only does it take years for qualified, law-abiding applicants to score a visa, but it needlessly blocks millions of others from ever coming here—regardless of their needs or talents. That’s bad for them, and it’s bad for us—stymying cultural diversity, economic growth, and innovation, while encouraging more chaos at our borders. So if you support immigration, as many people claim they do, you should support fundamental reforms to these laws (along with more resources for not just mor border enforcement but for processing and adjudication of legal immigration activities)—reforms that make it much easier for people to come here lawfully instead of waiting around, giving up, or choosing unlawful, often dangerous means of achieving their migration goals.

No use waiting in a line that never moves.

Capitolism will be off next week.

Chart of the Week