There is significant economic literature investigating the hostility to cash or “war on cash” (Beretta 2005, 2007; Deutsche Bundesbank 2017; Jain 2017; Scott 2013; White 2018) by which financial institutions supported by governments discourage individuals from using (publicly issued) physical means of payments and convince them to move to digital (privately issued) ones.

Banks, in particular, have a strong incentive to move directly to electronic payment systems (Spar 2003: 413). The term “war” might sound like “a polemical exaggeration” (Rogoff 2017), but there is little doubt that “persuasion work” by those who want to replace cash with digital currency is prevalent (Nagata 2019). In a “bankful society,” banks (or platforms built on top of them like PayPal) intermediate even small payments.

The Covid-19 pandemic has given digitization a boost through physical lockdowns and fear that physical cash may help spread the virus (see Klein 2020a). This article examines the influence of both the financial sector and governments on cash aversion prior to and after the outbreak of the pandemic.

We argue that cash has been unjustifiably accused of facilitating illicit transactions; the Covid-19 pandemic has been misused to push individuals away from banknotes and coins; and cash is even more welfare enhancing in troubled economic times. After a review of “instruments of convincement” used before the current pandemic, we show that since the pandemic hostility to cash has continued. We conclude by explaining why cash remains essential.

An Assessment of “Instruments of Convincement” to Abandon Cash before Covid-19

The main arguments against cash are money laundering and financing terrorism (Passas 2003) while those in favor of cash point to its practicality, better control of expenses, immediate finalization of settlement (Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures 2020), and better data protection (Mai 2019). In the following, we analyze less discussed methods to reduce cash’s influence in daily lives and identify the new “instruments of convincement” the financial institutions are using.

De Jure and De Facto Demonetization

Institutional aversion to cash has become particularly evident in India, where the government degraded its cash system (Pankaj and Jain 2017), or, from June to October 2019, in Kenya, where “7,386,000 pieces of the older KSh.1,000 notes, worth KSh.7.386 billion, were rendered worthless at the end of demonetization” (Central Bank of Kenya 2019). Demonetization might not be explicitly (i.e., de jure) declared but still (i.e., de facto) pursued, in the same way as the International Monetary Fund (2020a) distinguishes between de jure and de facto exchange arrangements. New banknote series combined with a tight deadline before losing their status of legal tender are a frequent approach to absorb part of circulating cash.

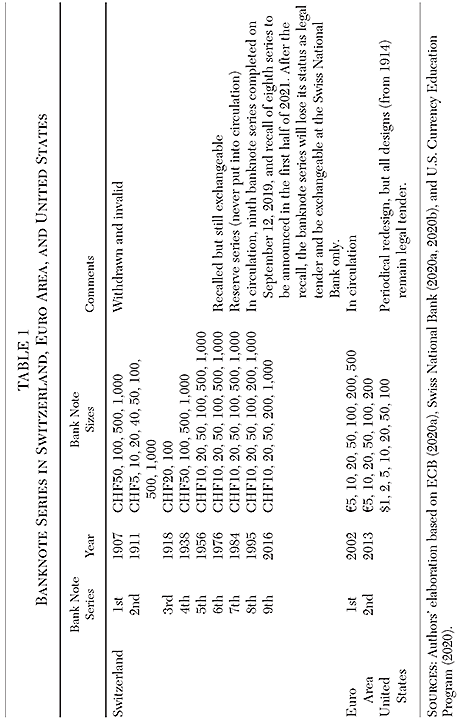

Table 1 compares the Swiss, Euro Area, and U.S. policy in terms of currency in circulation. For instance, while Switzerland will withdraw its eighth banknote series within a couple of months after its announcement in 2021, the euro area is still issuing the second series. In contrast, U.S. banknotes—provided they have been issued from 1914 onward—remain legal tender. This approach is often neglected by those who look at the United States solely as an example for payment digitization.

Another fact often glossed over is that, although credit cards originated in the United States during the 1920s (Britannica 2020), only European countries have decided to limit transactions settled in cash.

Promotional Campaigns, “Nudges,” and Shutdowns of ATMs: Why Seigniorage Matters

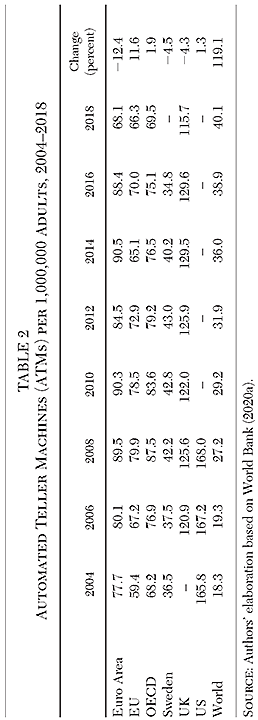

Movements against cash have also taken explicit forms—for example, Visa has launched “Cashfree and Proud” (Payment Week 2016) in order to “persuade British consumers that contactless was better than cash” (Jon Ashwell Creative 2020)—amidst a subtle drive to make cash inconvenient. People are told to be dodgy if they do not wish to comply with new ways of paying (Economic Times 2020) and cash is displayed as a “barbarous relic” (Financial Times 2015). Shutting down ATMs has been another approach, although “regulators seek to safeguard consumer access to cash as branches and free-to-use ATMs disappear” (Makortoff 2020). As shown in Table 2, there is not yet a pronounced trend toward shutting them down at the global level. This has been however the case in advanced countries.

There is a remarkable tendency to “nudge” consumers toward digital payment services (Scott 2016). Central bank notes and coins are public utilities that generate “costs of handling”—and cannot be used by commercial banks and financial institutions to earn profitst (G4S Retail Cash Solutions 2020). Rather, it is the government that gains from the supply of fiat money (Bergsten 1996: 209−10). For instance, the Swiss National Bank (2020c) has declared that “the cost of producing Swiss banknotes depends on the note’s size (denomination) and on the production volume, and generally averages around 40 centimes.” The largest banknote issued by the Swiss National Bank has a nominal value of CHF1,000; the seigniorage for this size might reach CHF999.60 and yield a profit margin of 99.96 percent. It is therefore understandable that private financial actors push consumers toward private digital money. Individuals should be convinced that they are “choosing” digital payments, which resembles how several supermarkets inspire consumers to “choose” unhealthy food by placing it at eye level by the checkout counters (Aydogan and Van Hove 2015). Once adaptation processes have begun, compliance becomes the most likely outcome.

Currency in Circulation: A Not-to-Be-Stopped Trend

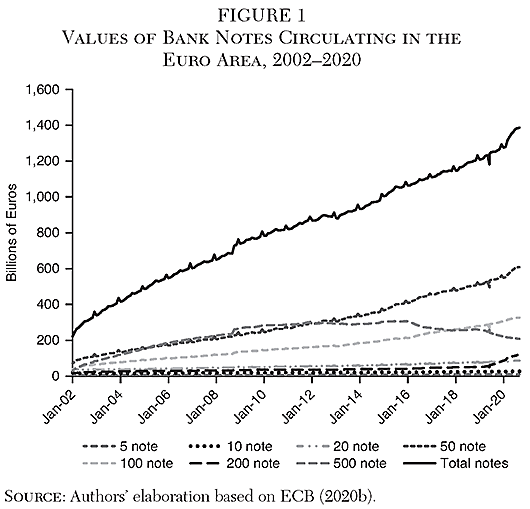

Despite “nudges” driving individuals toward technologically advanced financial solutions, circulating banknotes issued by the ECB (European Central Bank) are growing (Figure 1). While euro area GDP (at market prices) has increased 21.63 percent from 2002 to 2019 (World Bank 2020b), circulating banknotes have soared 475.63 percent (ECB 2020b).

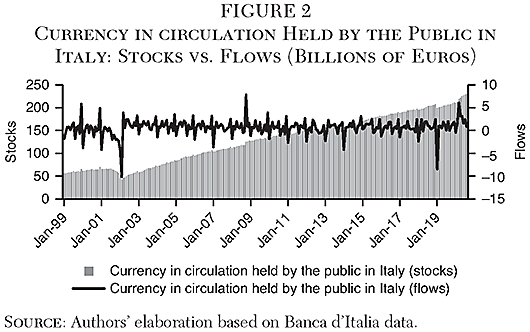

The ECB may have overissued means of payments, but Figure 2 is not sufficient to prove this argument. Another interpretation is that the ECB has responded to a strong demand for the legal tender. Our hypothesis is that cash is an inclusive, privacy-preserving, public means of settlement while digital payments privatize the banking and financial system gentrifying payments. According to White (2018: 485), “Well-meaning supporters of the ‘war on cash’ should ask themselves whether the war is really in the public’s interest rather than only in the private interest of tax authorities and incumbent payment service providers.” Figure 2 displays the increase of currency in circulation in Italy as of March 2020 held by the public just before the first Covid-19-related lockdown of a European country.

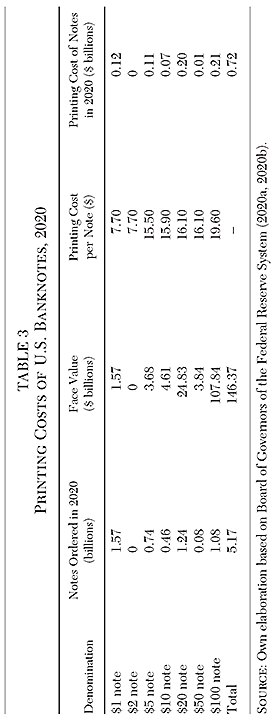

Banknotes issued by the ECB are the only form of legal tender with mandatory acceptance and no levying of fees permitted (Mersch 2018). Banknotes and coins have been also defined as “safe, sound or stable money . . ., plain money (J. Huber / J. Robertson), pure money (R. Striner), chartal money (derived from chartalism), state money (R. Werner), public money (K. Yamaguchi, M. Melior), constitutional money (R. Morrison) and, specifically in the United States, U.S. money (S. Zarlenga)” (Huber 2020). Although e‑cash is still in the works, because of its missing physicality, it will not represent a perfect substitute (Belke and Beretta 2020c). It would increase our reliance on digital systems, which might malfunction or break down (Dowd 2019a: 395; 2019b; 2019c). Payment systems operated by central banks are just as vulnerable to hacker attacks and equipment failures as those operated by commercial banks (Selgin 2018). Moreover, central bank digital money might increase inflationary money issues due to shrinking production and maintenance costs. The United States has paid printing costs of banknotes equal to $0.72 billion. in 2020 (Table 3), which is not significant at first sight. If physical cash were replaced by central bank digital money, printing costs would shrink and increase the seigniorage profit. E‑cash might propel overlending while exposing the central bank—if it should collect deposits from the general public—to risks from the need to comply with the “know your customer” (KYC) and “anti-money-laundering” (AML) principles (Pundrik 2009; Verhage 2011).

As highlighted by Mersch (2020):

Some 76 percent of all transactions in the euro area are carried out in cash, amounting to more than half of the total value of all payments. . . . In crisis times, the demand for cash surges even higher. At mid-March this year, the weekly increase in the value of banknotes in circulation almost reached the historical peak of €19 billion.

Because of their tangibility, banknotes and coins are considered safe. Furthermore, “holding cash physically does significantly change subjects’ behaviors by way of decreasing . . . their investment amount when they do participate” (Shen and Takahashi 2017: 4).

In addition, funds in commercial bank accounts are IOUs promising savers to get access to public money, namely a “spontaneous acknowledgement of debt” (Cencini 2002: 11). However, money cannot be compared to public debt with low interest rates (Rogoff and Scazzero 2021: 2), since the first one is an irredeemable IOU of the banking system toward the economy as a whole while the second one has to be reimbursed by a specific agent (i.e., the state, which should be independent from the central bank and vice versa) to the benefit of others (i.e., savers buying these bonds). In general, “the dollar is nothing more than an IOU, and only has value . . . under the illusion . . . that the government or institution which issues this paper has the power, wealth, and credit to back up this currency” (Goodbaudy 2011: 86). Since commercial banks need cash (public money) when customers want to cash in their demand deposits (private money), it is essential that commercial banks keep sufficient reserve balances at the central bank.

The reciprocal indebtedness of the commercial and central banks stands for the substitutability of money issued by the same banking system. Each time savers make use of ATMs to withdraw cash they leave the digital banking system. Hence, the private payments industry needs to convince people that public cash systems are less efficient than private systems, although on this conclusion there is some disagreement (e.g., Van der Kroft and Zijp 2019).

At the same time, “governments discourage cash transactions with the intention to fight tax evasion and money laundering” (Brunnermeier and Niepelt 2019: 27). However, this neglects that the two conditions for illicit transactions—untraceability and immediate transferability—are not guaranteed by physical payment methods for medium−large transactions (Beretta 2007). “The physical movement of large quantities of cash is the money launderer’s biggest problem” (Molander et al. 1998: xi).

The Myth of Facilitating the Shadow Economy

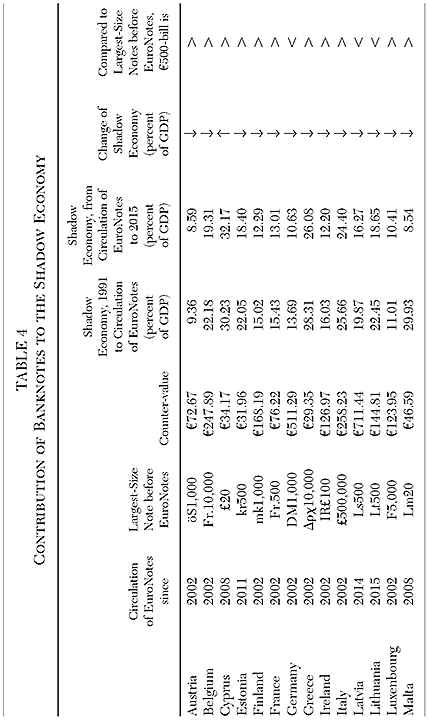

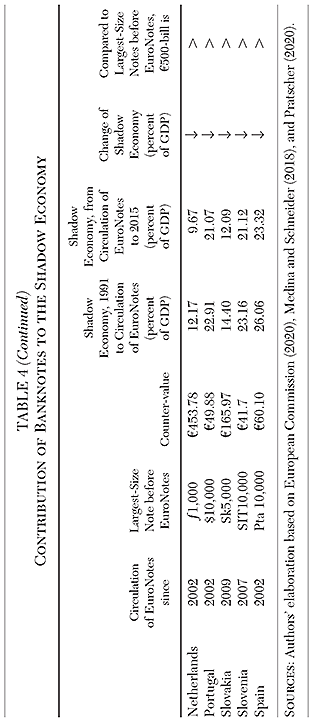

According to Rogoff (2017: 114), “Paper currency has always facilitated tax evasion and crime. . . . The $100-bill and the €500-note, for example, are relatively unimportant in everyday retail transactions. Yet they dwarf small bills in their share of currency supplies.” However, the evidence in Table 4 shows that the introduction of large-scale notes has not facilitated the shadow economy, defined as “all economic activities which are hidden from official authorities for monetary, regulatory, and institutional reasons” (Medina and Schneider 2018: 4).

Although the €500 banknote is larger than most of the previously circulating notes, the shadow economy (as a percentage of GDP) has decreased. Either the €500 banknote does not (significantly) contribute to tax evasion and money laundering or its impact can be compensated by a common, stricter monetary regulation framework like the European. In both cases, we cannot confirm the alleged link between large-size notes and the shadow economy. Moreover, “there is no need to criminalize cash itself to prosecute someone engaged in criminal activity or to ignore law-abiding citizens’ right to personal and financial privacy” (Michel 2018: 49). Rather, much more criminal activity is conducted with digital money than with cash. Nowadays, the ideal medium for illegal drug transactions is not cash, but Amazon gift cards. Gift tokens allow for anonymous payments anywhere in the world and, unlike cash, do not require a face-to-face transaction. The same holds for prepaid credit cards, which can be loaded with cash anonymously. Digital money also has the advantage over cash that it can be used much more easily for large amounts of illegal transactions (Dowd 2019a: 393; 2019b; 2019c).

Cash Payment Limitations in Periods of (Deregulated) Cryptocurrencies: A Counterintuitive Trend

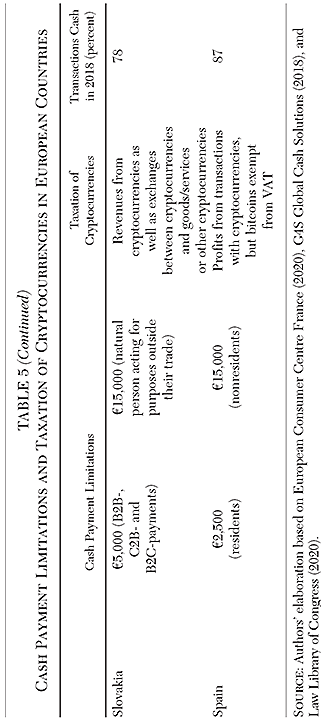

A private payments system is also exposed to “modern monetary Middle Ages” (Belke and Beretta 2020b) resembling the status quo before the establishment of central banks, namely modern regulators of seigniorage and money issue rights (Das and Basu 2016: 127). Granting everyone the right to mint private monies à la cryptocurrencies “out of thin air” (i.e., nominally) to pay real-terms purchases reflects a threatening deregulation. How can a “nonvalue” like money settle real-term transactions? In fact, “money’s value is purely derivative; money has no value of its own. . . . The entire economy is the backing of the currency” (Parsson 2011: 141), because “nobody can create wealth or positive purchasing power by a stroke of a pen, but just excess (and, therefore, inflationary) liquidity (Belke and Beretta 2020a: 932). While de facto tolerating a breakup of the governmental money monopoly, European states have introduced cash payment restrictions after the 2008 global financial and economic crisis. Although cryptocurrencies are mined with no real backing, traded, and used to settle real-terms transactions, states are paradoxically limiting their legal tender status. In fact, “there are clear signs that the use of cash is being increasingly restricted inside the European Monetary Union (EMU)” (Siekmann 2017: 154). Table 5 explores whether countries limiting cash payments are prone to use banknotes and coins. Are policymakers of such nations also taxing (i.e., regulating) cryptocurrencies?

While in some European nations cryptocurrencies are neither regulated nor taxed, in others governments levy taxes on their use. However, both approaches are inadequate. While the absence of regulation and taxation reduces the right to issue money to a mere formality, taxing something with no intrinsic value (because of having been created from scratch) is economic nonsense. Cash payment restrictions, despite the dominance of transactions in cash (e.g., last column of Table 5), confirm the top-down approach to money. As analyzed in Beretta (2015), the proposal for a “financial transaction tax” (FTT), in combination with bank accounts potentially subject to haircuts (e.g., during the 2012–2013 Cyprus banking crisis), is not a coherent strategy encouraging a cashless society.1

How Hostility to Cash Has Evolved after Covid-19

In the wake of the pandemic, banknotes and coins have been analyzed from a health-related perspective. In this section, we show that any potentially legitimate concern should be also extended to cashless payments. The fact that payments in cash may be shrinking should not let us gloss over the increasing relevance of bank notes and coins as stores of value. The coexistence of digital currency and physical means of payments is not a scenario to fight against.

Does Cash Carry Viruses?

With the Covid-19 pandemic, the argument that cash is “dirty” has become visceral. This criticism is not new, since Maritz et al. (2017) have pointed out that “shotgun metagenomics identified eukaryotes as the most abundant sequences on money, followed by bacteria, viruses and archaea.” After the outbreak of the pandemic, mass-consumption stores have been moving from cash to cashless payments. A survey conducted in Switzerland in April 2020 about payment methods in times of Covid-19 has shown that “over one-third of respondents have increased the number of digital payments or contactless payments” (Egerth 2020). This is an opportunity to consolidate and extend the economic power of big corporations whose payments systems are “systemically important” as defined by the Bank for International Settlements. According to preliminary studies, “the move to a cashless society has been accelerated by the perceived risk of infection via hard currency” (Thomalla and Schnippe 2020) while global tech players have massively expanded their power (Klein 2020a). For instance, Amazon.com (2020) has announced that its “operating cash flow increased 56 percent to $55.3 billion, [while net] sales increased 37 percent to $96.1 billion in the third quarter.” The digital payments industry clearly aims at achieving synergies with technologically automatized sectors, since “cash doesn’t play well with Amazon’s desire for fully automated systems” (CQ Researchers 2019).

The pandemic has changed the way individuals interact with each other (Fetters 2020). However, there is no scientific evidence that banknotes and coins pose a special risk in carrying viruses. According to the Bank of England (2020), the “risk posed by handling a bank note is not greater than touching any other common surface.” Indeed, anything touchable might transmit viruses, including credit/debit/ATM cards and contactless payment methods (where the smartphone might become “contaminated” during the settlement process. Olsen et al. (2020: 1), for example, point out that, “as possible breeding grounds for microbial organisms, [mobile phones] constitute a potential global public health risk for microbial transmission.” It is not how people pay for something that poses a risk, but what they do afterward with their hands. More precisely,

without a perfect storm of transmission conditions—someone sneezes on a bank note, doesn’t allow it to dry, stores it someplace dark and humid, doesn’t rub it on other material like a leather wallet or pants pocket—maybe, and only maybe, enough viral particles could survive to infect the next person handling those bills” [Wolman 2013].

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (2020) has recently added that “at 20 degrees Celsius the virus was extremely robust, surviving for 28 days on smooth surfaces such as glass found on mobile phone screens and plastic bank notes.” This confirms that hygiene is at risk independently from payment methods, but dependently from people’s behaviors.

Nevertheless, the German Savings Banks Finance Group employing more than 300,000 workers and running 385 bank branches (Sparkasse 2020) is promoting its contactless payment methods at prime-time hours by means of the so-called Mainzelmännchen (i.e., a German comic figure with an iconic status). The underlying symbolism is evident. But, even before, several articles claimed that “dirty bank notes may be spreading the coronavirus, WHO suggests” (The Telegraph 2020), which prompted Fadela Chaib, a spokesperson of the World Health Organization, to specify that “we did NOT say that cash was transmitting coronavirus” (MarketWatch 2020). The banking industry in the UK was meanwhile taking advantage of such uncertainty and increasing the contactless payments limit from £30 to £45 (UK Finance 2020).

Banknotes and Coins in Crisis Times: From Means of Payment to Stores of Value

Despite marketing efforts of the financial sector in support of cashless payments, cash withdrawals and “currency in circulation ha[ve] actually surged in a number of countries” (Ashworth and Goodhart 2020) right before lockdowns. Hence, especially during severe crises (The Economist 2020), cash is valued more than in usual times. A comparable phenomenon has also occurred when fears about the future of the euro and a potential “Grexit” have arisen before Mario Draghi’s (2012) “whatever it takes.”

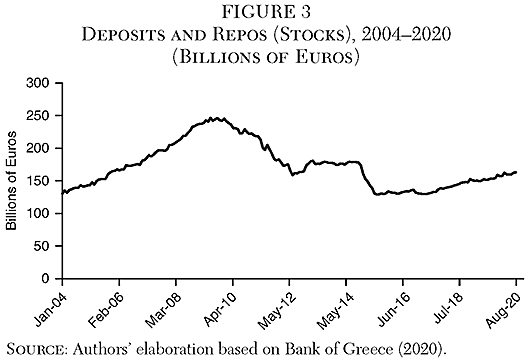

As highlighted in Figure 3, the stock of deposits and repos in Greece plummeted by more than €100 billion. People use cash to leave an unstable banking system and withdraw savings before an impending hurricane or war, or also after large shocks caused by epidemics (Goodell 2020). This represents a “precautionary demand for cash” (Plessner and Reid 1980: 427). Without banknotes and coins there would be fewer bank runs during crises, since savers would no longer have the possibility to withdraw their deposits. However, individuals would replace traditional bank runs with digital ones (Pinsent Masons 2018), losing an efficient way to rescue their savings. In this case, financial crises would endanger social and economic wealth even more. This is not much different from an unexpected, catastrophic event like the attacks on September 11, 2001, when “airlines with lower levels of cash and equivalents to total assets were penalized most” (Carter and Simkins 2004: 17). Under today’s circumstances, the catastrophe is Covid-19 while cash (i.e., liquidity) maintains its role as an anchor of stability.

A major difference between the 2009 European debt crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic (2020) is that the first one has been endogenous to the financial system while the latter is exogenous. If banknotes and coins have been perceived more spendable than funds in unstable banks during the European debt crisis, whenever individuals are not able to leave their homes due to lockdowns, cashless payments are “an obliged choice.” Perhaps, “contactless card payments may have replaced a certain share of cash payments permanently. However, the new payment mix will not become fully apparent until consumer habits normalize after the pandemic” (Mai 2020: 1).

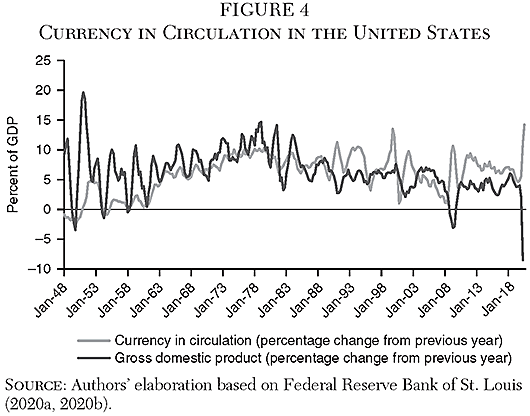

But even if payments settled in banknotes and coins should have (further) decreased due to the pandemic, no strong conclusions about the future can be drawn. Cash is not only a means of payment but also a store of value. This “double feature” is particularly relevant in economic systems detached from precious metals. Cash has become the “new gold” to which paper money has been itself convertible before August 15, 1971 (i.e., before the demonetization of gold by President Richard Nixon). Banknotes and coins are not a “barbarous relic” after observing historical data about their circulation. For instance, in 1918 U.S. cash corresponded to $4.37 billion while in 1938 it was $6.51 billion. The big increase started right during World War II ($12.68 billion in 1942), became even more pronounced after the demonetization of gold ($58.07 billion in 1971) and reached $1,745.10 billion in 2019 (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 2020a). Bank notes and coins have therefore increased by almost 40 percent within a century. Once again, an increase of digital payments is not in contradiction with cash as an epitome of means of payments and store of wealth.

This is also proven by Figure 4 depicting the increase/decrease of the currency circulating in the United States as compared to GDP variations. From the 1990s, the demand for currency has surged more than economic growth while the 2010s have been even more characterized by increases of currency in circulation. However, 2020 is the year that truly highlights that banknotes and coins have become—especially, in troubled economic times—an “anchor of stability.” This is not astonishing, since tangibility remains an irreplaceable characteristic. Since stores of value (i.e., wealth) are greater in amount than means of payments (i.e., net income), the role of banknotes and coins is not at risk because of individuals’ behaviors. However, policymakers might reduce their usability by means of a top-down approach. If so, the stability of the global economic and financial system would be threatened and savers would have no alternative to digital money and bank deposits.

Conclusion

We conclude that institutional hostility to cash has been accelerated by great shocks, beginning with the 2008 financial crisis and continuing with the current pandemic. However, the narratives of both the private financial sector and governments about the disadvantages of paying with cash or using large banknotes are partly flawed.

Eliminating cash would not only increase financial instability and market power of the financial sector, but also lead to financial exclusion and social discrimination with severe adverse effects on the vulnerable (Dowd 2019a: 394–95), adding to the impact of the pandemic on inequality (Stiglitz 2020). According to Access to Cash Review (2019: 6), “around 17 percent of the UK population—over 8 million adults—would struggle to cope in a cashless society. . . . For a start, poverty is the biggest indicator of cash dependency, not age.” The pandemic has set in motion a major economic downturn—the International Monetary Fund (2020b) forecasts a drop in world output by 4.4 percent—and banks are likely to adopt more conservative lending policies (Goodell 2020). Among the most penalized subjects are “the unbanked” (King 2014) and “the underbanked” having “limited access to services” (Wherry and Schor 2015: 174).

Like every disaster, the pandemic is a magnifier and intensifier of social discrimination (Klein 2020b). By accelerating digitalization—retail sales via mail order houses or the internet have soared in the European Union from 166.4 (March 2020) to 185.2 (September 2020) with 2015=100 (Eurostat 2020)—it uncovers the lack of access to the internet or insufficient digital literacy of social groups. This divide also concerns access to financial services in advanced countries where bank branches are closed to increase cost efficiency (Conrad et al. 2019). Combined with lockdowns, this trend will have a negative impact on physical retail stores, which are already struggling to cope with digital (i.e., 24-hours-a-day-running) competitors. At the same time, a cash-free commerce obliterates people’s privacy and entrenches racial and gender discrimination. In fact, “any person or company with access to the bank statement of the consumer can learn a lot of information about his/her financial and personal life by analyzing their payment transactions” (Bureau Européen des Unions des Consommateurs, AISBL 2019: 14).

Covid-19 should not become a war on cash, because there is no need to create tension between cashless and physical means of payments. In fact, both have proven to be useful depending on the situation while banknotes and coins are also stores of value. This is something not replaceable in gold-detached systems whose “anchor of stability” is (physical) cash.

References

Access to Cash Review (2019) “Final Report, March 2019.” Available at www.accesstocash.org.uk/media/1087/final-report-final-web.pdf.

Amazon.com (2020) “Press Release: Amazon.com Announces Third Quarter Results (October 29).” Available at press.aboutamazon.com/news-releases/news-release-details/amazoncom-announces-third-quarter-results.

Ashworth, J., and Goodhart, C. (2020) “Coronavirus Panic Fuels a Surge in Cash Demand.” Available at voxeu.org/article/coronavirus-panic-fuels-surge-cash-demand.

Aydogan, S., and Van Hove, L. (2015) “Nudging Consumers towards Card Payments: A Field Experiment.” In Deutsche Bundesbank (ed.), The Usage, Costs and Benefits of Cash Revisited. Frankfurt am Main: Deutsche Bundesbank.

Bank of England (2020) “Questions about Guidelines for Handling Old and Mutilated Banknotes during the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Available at www.bankofengland.co.uk/freedom-of-information/2020/questions-about-guidelines-handling-old-and-mutilated-banknotes-covid-19-pandemic.

Bank of Greece (2020) “Deposits and Repos of Non MFIs in MFIs in Greece (Excluding the Bank of Greece)—Outstanding Amounts at End of Period.” Available at opendata.bankofgreece.gr/datasetFile.ashx?fileName=BoG_DepositStock_en_2020-08–27.xls&folderName=STATISTIKI.

Belke, A., and Beretta, E. (2020a) “From Cash to Central Bank Digital Currencies and Cryptocurrencies: A Balancing Act between Modernity and Monetary Stability.” Journal of Economic Studies 47 (4): 911–38.

__________ (2020b) “From Cash to Private and Public Digital Currencies: The Risk of Financial Instability and ‘Modern Monetary Middle Ages.’” Economics and Business Letters 9 (3): 189–96.

__________ (2020c) “Not the Time for Central Bank Digital Currency: Why Cash Is Still Irreplaceable.” Credit and Capital Markets/Kredit und Kapital 53 (2): 147–58.

Beretta, E. (2007) “Cash Restrictions, Alias the EU’s Brake on Growth: New Analytical and Empirical Evidence.” Currency News 15 (7): 7.

__________ (2015) “Europe’s New but Wrong Approach to Cash.” Currency News 13 (4): 5–8.

Bergsten, F. (1996) Dilemmas of the Dollar: the Economics and Politics of United States International Monetary Policy. 2nd ed. New York: Council on Foreign Relations.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2020a) “Currency and Coin Services: 2020 Federal Reserve Note Print Order.” Available at www.federalreserve.gov/paymentsystems/2020_currency_print_orders.htm.

__________ (2020b) “FAQs—How Much Does It Cost to Produce Currency and Coin?” Available at www.federalreserve.gov/faqs/currency_12771.htm.

Britannica (2020) “Credit Card.” Available at www.britannica.com/topic/credit-card.

Brunnermeier, M. K., and Niepelt, D. (2019) “On the Equivalence of Private and Public Money.” Journal of Monetary Economics 106: 27–41.

Bureau Européen des Unions des Consommateurs, AISBL (2019) “Cash versus Cashless. Consumers Need a Right to Use Cash.” Available at www.beuc.eu/publications/beuc-x-2019–052_cash_versus_cashless.pdf.

Carter, D. A., and Simkins, B. J. (2004) “The Market’s Reaction to Unexpected, Catastrophic Events: The Case of Airline Stock Returns and the September 11th Attacks.” Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 44: 539–58.

Cencini, A. (2002) Monetary Theory: National and International. New York: Routledge.

__________ (2005) Macroeconomic Foundations of Macroeconomics. New York: Routledge.

Central Bank of Kenya (2019) “Press Release: Conclusion of Demonetization Exercise.” Available at www.centralbank.go.ke/uploads/press_releases/735017284_Press%20Release%20-%20Conclusion%20of%20Demonetisation%20Exercise.pdf.

Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (2020) “Final Settlement.” Available at www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d00b.htm?&selection=30&scope=CPMI&c=a&base=term.

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (2020) “CSIRO Scientists Publish New Research on SARS-COV‑2 Virus ‘Survivability.’” Available at www.csiro.au/en/News/News-releases/2020/CSIRO-scientists-publish-new-research-on-SARS-COV-2-virus-survivability.

Conrad, A.; Neuberger, D.; Peters, F.; and Rösch, F. (2019) The Impact of Socio-economic and Demographic Factors on the Use of Digital Access to Financial Services.” Credit and Capital Markets–Kredit und Kapital 52 (3): 295–321.

CQ Researchers (2019) Global Issues 2020 Edition: Selections from CQ Researcher. Washington: CQ Press.

Das, A., and Basu, K. (2016) S. Chand’s ICSE Economic Applications:Book II for Class X. New Delhi: S. Chand.

Deutsche Bundesbank (2017) International Cash Conference 2017. War on Cash: Is There a Future for Cash? Frankfurt am Main: Deutsche Bundesbank.

Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union (2012) “FTT—Additional Analysis of Impacts and Further Clarification of Practical Functioning—4 May 2012.” Available at ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/sites/taxation/files/docs/body/technical_fiches.pdf.

Dowd, K. (2019a) “The War on Cash Is about Much More than Cash.” Economic Affairs 39: 391–99.

__________ (2019b) “We Mustn’t Lose the War on Cash.” Institute of Economic Affairs blog (November 14).

__________ (2019c) “The War on Cash Is no Use in the War on Crime.” Investment Foresight: Online Business Magazine (December 10).

Draghi, M. (2012) “Verbatim of the Remarks Made by Mario Draghi.” Speech at the Global Investment Conference, London (July 26). Available at www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2012/html/sp120726.en.html.

Economic Times (2020) “How Cash Turned Suspicious under COVID-19.” Economic Times (May 20).

Egerth, K. (2020) “Cash Is no Longer King in Times of COVID-19: Raining on Cash’s Reign.” Available at www2.deloitte.com/ch/en/pages/consumer-industrial-products/articles/cash-is-no-longer-king-in-times-of-covid19.html.

European Central Bank (ECB) (2020a) “Banknotes.” Available at www.ecb.europa.eu/euro/banknotes/html/index.en.html.

__________ (2020b) “Banknotes and Coins Circulation.” Available at www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/policy_and_exchange_rates/banknotes+coins/circulation/html/index.en.html.

European Commission (2020) “What Is the Euro Area?” Available at ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/euro-area/what-euro-area_en.

European Consumer Centre France (2020) “Cash Payment Limitations.” Available at www.europe-consommateurs.eu/en/consumer-topics/financial-services-insurance/banking/means-of-payment/cash-payment-limitations.

Eurostat (2020) “Turnover and Volume of Sales in Wholesale and Retail Trade. Monthly Data. Retail Sale via Mail Order Houses or via Internet.” Available at appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (2020a) “Currency in Circulation.” Available at fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CURRCIR.

__________ (2020b) “Gross Domestic Product.” Available at fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GDP.

Fetters, A. (2020) “When Keeping Your Distance Is the Best Way to Show You Care.” The Atlantic (March 10).

Financial Times (2015) “The Case for Retiring Another ‘Barbarous Relic.’” Financial Times (August 23).

G4S Global Cash Solutions (2018) “World Cash Report 2018.” Available at cashessentials.org/app/uploads/2018/07/2018-world-cash-report.pdf.

G4S Retail Cash Solutions (2020) “Exceptional Value within G4S.” Available at www.g4s.com.

Goodbaudy, T. (2011) You Don’t Want to Read What This Man Has to Say! Portland: PDXdzyn.

Goodell, J. W. (2020) “COVID-19 and Finance: Agendas for Future Research.” Finance Research Letters 35: 101512.

Huber, J. (2020) “What Is Sovereign Money?” Available at sovereignmoney.site/what-is-sovereign-money.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2020a) Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions 2019. Washington: IMF.

__________ (2020b) “World Economic Outlook Update, October 2020. A Long and Difficult Ascent.” Washington: IMF.

Jain, K. (2017) The War on Cash. Demonetisation. New Delhi: Educreation.

Jon Ashwell Creative (2020) “Cashfree and Proud.” Available at jonashwellcreative.weebly.com/visa-cashfree—proud.html.

King, B. (2014) Breaking Banks: The Innovators, Rogues, and Strategists Rebooting Banking. Singapore: Wiley.

Klein, N. (2020a) “How Big Tech Plans to Profit from the Pandemic.” The Guardian (May 13).

__________ (2020b) “We Must not Return to the Pre-Covid Status Quo, Only Worse.” The Guardian (July 13).

Law Library of Congress (2020) “Regulation of Cryptocurrency around the World.” Available at www.loc.gov/law/help/cryptocurrency/world-survey.php.

Mai, H. (2019) “Cash Empowers the Individual through Data Protection.” Available at www.dbresearch.de.

__________ (2020) “Paying in Times of Crisis: Coronavirus, Cards and Cash.” Available at www.dbresearch.com.

Makortoff, K. (2020) “UK Banks May Have to Flag up Plans to Shut Branches or Cash Machines.” The Guardian (July 16).

Maritz, J. M.; Sullivan, S. A.; Prill, R. J.; Aksoy, E.; Scheid, E.; and Carlton, J. M. (2017) “Filthy Lucre: A Metagenomic Pilot Study of Microbes Found on Circulating Currency in New York City.” PLOS ONE 12 (4): e0175527. Available at https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175527.

MarketWatch (2020) “World Health Organization: ‘We Did NOT Say That Cash Was Transmitting Coronavirus.’” MarketWatch.com. (March 6).

Medina, L., and Schneider, F. (2018). “Shadow Economies around the World: What Did We Learn Over the Last 20 Years?” IMF Working Paper No. 18/17.

Mersch, Y. (2018) “The Role of Euro Banknotes as Legal Tender.” Available at www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2018/html/ecb.sp180214.en.html.

__________ (2020) “An ECB Digital Currency: A Flight of Fancy?” Available at www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2020/html/ecb.sp200511~01209cb324.en.html.

Michel, N. J. (2018) “Special Interest Politics Could Save Cash or Kill It.” Cato Journal 38 (2): 489–502.

Molander, R. C.; Mussington, D. A.; and Wilson, P. A. (1998) Cyberpayments and Money Laundering: Problems and Promise. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND.

Nagata, K. (2019) “Can a Tax Rebate Persuade Japan’s Mom-and-Pop Stores to Shift to Cashless Payments?” Japan Times (September 1).

Olsen, M.; Campos, M.; Lohning, A.; Jones, P.; Legget, J.; Bannach-Brown, A.; McKirdy, S.; Alghafri, R.; and Tajouria, L. (2020) “Mobile Phones Represent a Pathway for Microbial Transmission: A Scoping Review.” Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 35: 101704.

Pankaj, P., and Jain, S. (2017) The Demonetization Phenomenon. New York: Bloomsbury Prime.

Parsson, J. O. (2011) Dying of Money. Indianapolis: Dog Ear.

Passas, N. (2003) “Informal Value Transfer Systems, Terrorism and Money Laundering: A Report to the National Institute of Justice.” Available at www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/208301.pdf.

Payment Week (2016) “Visa Europe: Cashfree and Proud, Complete with Celebrities.” Payment Week.com (March 23).

Pinsent Masons (2018) “‘Digital Bank Run’ a Risk Should Central Banks Issue Their Own Virtual Currency, Says Weidmann.” Available at www.pinsentmasons.com.

Plessner, Y., and Reid, J. D. Jr. (1980) “The Precautionary Demand for Money. A Rigorous Foundation.” Journal of Monetary Economics 6 (3): 419–32.

Pratscher, S. (2020) “The Former Currencies of the Eurozone.” Available at webs.schule.at/website/European_Currencies/old_eu_currencies_en.htm.

Pundrik, M. (2009) Sales Management. Keys to Effective Sales. New Delhi: Global India.

Rogoff, K. S. (2017) The Curse of Cash: How Large-Denomination Bills Aid Crime and Tax Evasion and Constrain Monetary Policy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Rogoff, K. S., and Scazzero, J. (2021) “Covid Cash.” Cato Journal 41 (3): 571–92.

Scott, B. (2013) The Heretic’s Guide to Global Finance: Hacking the Future of Money. London: Pluto Press.

__________ (2016) “The Cashless Society Is a Con and Big Finance Is Behind It.” The Guardian (July 19).

Selgin, G. (2018) “The Computer-Glitch Argument for Central Bank eCash.” Alt‑M (June 7).

Shen, J., and Takahashi, H. (2017) “The Tangibility Effect of Paper Money and Coin in an Investment Experiment.” Economics and Business Letters 6 (1): 1–5.

Siekmann, H. (2017) “Restricting the Use of Cash in the European Monetary Union: Legal Aspects.” In: F. Rövekamp; M. Bälz, and H. G. Hilpert (eds.), Cash in East Asia. New York: Springer.

Spar, D. L. (2003) Managing International Trade and Investment: Casebook. London: World Scientific.

Sparkasse (2020) Die Sparkassen-Finanzgruppe als Arbeitgeber. Available at www.sparkasse.de/karriere/unternehmen.html.

Stiglitz, J. (2020) “Conquering the Great Divide.” Available at www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/09/COVID19-and-global-inequality-joseph-stiglitz.htm.

Swiss National Bank (2020a) “All SNB Banknote Series.” Available at www.snb.ch/en/iabout/cash/history/id/cash_history_overview#t4.

__________ (2020b) “Announcement Regarding Recall of Banknotes from Eighth Series.” Available at www.snb.ch/en/iabout/cash.

__________ (2020c) “Costs.” Available at www.snb.ch/en/iabout/cash/cash_lifecycle/id/cash_lifecycle_costs.

The Economist (2020) “Daily Chart. Why Cash Has Been Piling Up during the Pandemic.” Available at www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2020/08/13/why-cash-has-been-piling-up-during-the-pandemic.

The Telegraph (2020) “Dirty Banknotes May Be Spreading the Coronavirus, WHO Suggests.” The Telegraph (March 2).

Thomalla, S., and Schnippe, M. (2020) “How COVID-19 Is Reshaping Retail Payments in Europe.” Available at www.ey.com/en_gl/banking-capital-markets/how-covid-19-is-reshaping-retail-payments-in-europe.

U.S. Currency Education Program (2020) “The Seven Denominations.” Available at www.uscurrency.gov/denominations.

UK Finance (2020) “Contactless Limit in UK Increases to £45 from Today.” Available at www.ukfinance.org.uk/press/press-releases/contactless-limit-uk-increases-£45-today.

Van der Kroft, J., and Zijp, A. (2019) “Will Slow Payment Systems Put the Brakes on Economic Growth?” Available at www.ey.com/en_gl/banking-capital-markets/will-slow-payment-systems-put-the-brakes-on-economic-growth.

Verhage, A. (2011) The Anti-Money Laundering Complex and the Compliance Industry. New York: Routledge.

Wherry, F. F., and Schor, J. (2015) The SAGE Encyclopedia of Economics and Society. Washington: SAGE.

White, L. H. (2018) “The Curse of the War on Cash.” Cato Journal 38 (2): 477–88.

Wolman, D. (2013) The End of Money: Counterfeiters, Preachers, Techies, Dreamers and the Coming Cashless Society. Boston: Da Capo.

World Bank (2020a) “Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) (per 100,000 Adults).” Available at data.worldbank.org/indicator/FB.ATM.TOTL.P5.

__________ (2020b) “GDP Growth (Annual %).” Available at data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?end=2019&start=1961.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.