The Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) first set a goal to balance the budget by cutting $2 trillion in waste, fraud, and abuse. This goal was later reduced to $1 trillion and then again to just $150 billion. DOGE also aimed to reduce the size and scope of the administrative state, improve the procurement process, reform regulations, eliminate certain small agencies, use technology to cut costs, and shrink the federal workforce. Cato scholars supported all these objectives. With DOGE now disbanded as a single entity, the main question is whether DOGE achieved its goals.

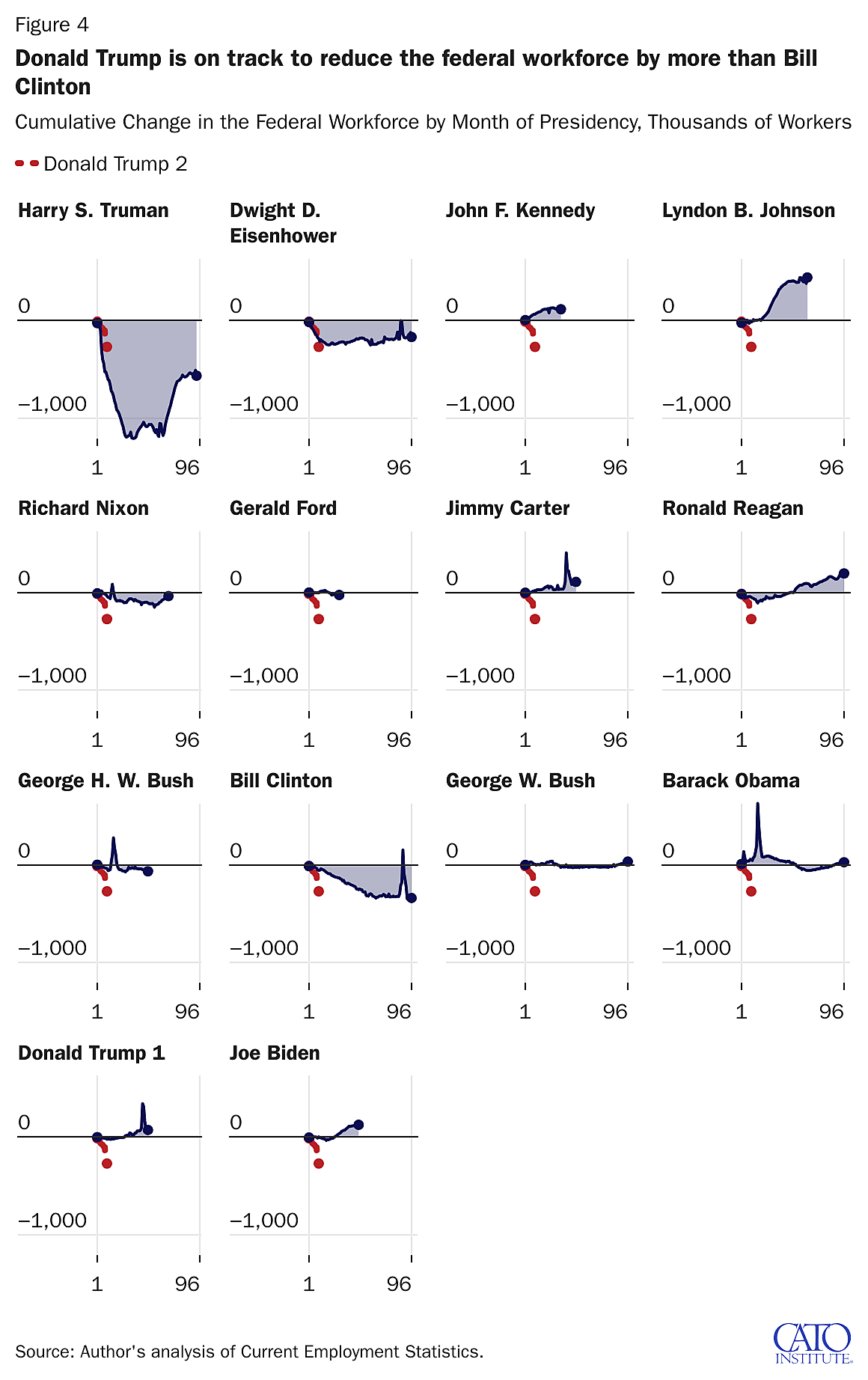

This analysis only focuses on federal outlays and employment. DOGE did not reduce spending, but it did reduce federal employment by nine percent in less than 10 months. A decline that large has not happened since the military demobilizations at the end of World War II and the Korean War (Figure 4).

Federal spending data are compiled by the Monthly Treasury Statements (MTS) published by the Bureau of the Fiscal Service. We focus exclusively on outlays, not budget authority, and on executive branch spending because that was DOGE’s jurisdiction. All dollar amounts are reported in 2021 dollars, adjusted using the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index. Federal employment data are from the Current Employment Statistics, which are monthly job surveys run by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Monthly data on the number of federal jobs is available here from January 1939 to November 2025. The October and November 2025 data may be highly variable because of the recent shutdown.

The federal government spent $7.6 trillion in the first 11 months of calendar year 2025, approximately $248 billion higher by November of 2025 compared to the same month in 2024 (Figure 1). Cumulative spending in every month of 2025 was greater than in every other year and was approximately as much as the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected in June 2024, or slightly less in real terms. There is no visible structural break in 2025 spending that coincides with DOGE’s start date. An observer who did not know when DOGE started could not identify it in Figure 1.

Any changes in spending during DOGE’s tenure compared to the CBO projection coincided with a rescission bill, as pointed out by Jessica Riedl. Although she is on methodologically sound ground by judging DOGE’s effect on spending relative to a CBO baseline, and we concur with her analysis, it is important to note that DOGE’s target was to reduce the budget in absolute real terms without reference to a baseline projection. DOGE did not cut spending by either standard.

DOGE failed to cut spending because most federal spending was for entitlement programs, where spending remains high due to structural reasons and policy autopilot. Congress alone has the authority to cut these programs, so it’s unsurprising that DOGE did not reduce spending.

Although DOGE didn’t reduce outlays by November, it sizably cut federal employment by 271,000 (Figure 2). That’s a nine percent decline since January 2025. DOGE brought down federal employment to late 2014 levels in less than 10 months, but with almost 60 percent of the decline in October. Figure 3 compares the monthly change in federal employment during the Biden administration and President Trump’s second term, while Figure 4 measures reductions in Trump’s 2025 workforce against previous presidents.

The pace of workforce reduction was unusually rapid and is on track to exceed Clinton-era cumulative reductions in roughly one year rather than four, if sustained. By the end of September, federal employment had fallen by almost 100,000. The sharp October drop of over 150,000 was driven by the federal civil service buyout offer rather than normal attrition. The number of employees continued to fall in November, but at a slower pace. We won’t see a single month of federal employment decline that resembles October 2025 for the rest of the Trump administration.

It is not surprising that such a large reduction in the federal workforce did not lead to lower outlays, since most federal expenditures are transfer payments rather than salaries. According to Cato’s report to the DOGE Commission last year, a 10 percent cut in the federal workforce would only save about $40 billion annually. The 3.8 million federal defense and nondefense employees, excluding postal workers, account for around 8 percent of total spending.

This is not an exact comparison to other figures in this post, but it helps explain why reducing the workforce does not result in large savings. Additionally, the feds may hire contractors to fill some of the space vacated by former federal employees.

Elon Musk recently said that DOGE was only “a little bit successful” and that he wouldn’t do it again. The evidence supports Musk’s judgment. DOGE had no noticeable effect on the trajectory of spending, but it reduced federal employment at the fastest pace since President Carter, and likely even before. The only possible analogies are demobilization after World War II and the Korean War. Reducing spending is more important, but cutting the federal workforce is nothing to sneeze at, and Musk should look more positively on DOGE’s impact.

A future commission like DOGE will require a more serious, congressionally approved plan to rein in spending, such as a BRAC-like fiscal commission. DOGE failed to reduce spending but achieved unmatched peacetime workforce cuts in a short span. Compared to earlier commissions, its record is unique. Future commissions could succeed if Congress empowers them and the administration backs government reduction.

DOGE did not reduce federal spending because most outlays are entitlement-driven and require congressional action, but it did help engineer the largest peacetime workforce reduction on record.