Senators Dick Durbin and Lindsey Graham have introduced a bill to extend the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which since 2012 has provided work permits and lawful presence to 800,000 young immigrants brought illegally to the United States as children. One difficulty for the bill is that the GOP House passed a bill to end DACA in 2014, arguing that DACA caused a surge of young children to come to the border starting in 2012 and reaching its peak in 2014.

At the time, my colleague Alex Nowrasteh published an article arguing against this thesis. First, he noted that DACA specifically prohibited recent arrivals from applying for the benefits. DACA applicants had to be under the age of 31, have arrived in the United States before they were the age of 16, and have continuously resided in the United States since June 15, 2007. Second, Nowrasteh explained that the surge began well before DACA was unexpectedly announced on June 15, 2012. He wrote:

From October 2011 through March 2012, there was a 93 percent increase in UAC arrivals over the same period in Fiscal Year 2011. Texas Governor Rick Perry warned President Obama about the rapid increase in UAC at the border in early May 2012 – more than a full month before DACA was announced. In early June 2012, Mexico was detaining twice as many Central American children as in 2011. The surge in unaccompanied children (UAC) began before DACA was announced.

As the bill was being debated on the House floor, Rep. Zoe Lofgren, the ranking member of the House Subcommittee on Immigration and Border Security, proceeded to introduce Nowrasteh’s article into the record as evidence against the underlying reason for the bill. Unfortunately, Border Patrol had not yet released their monthly UAC arrival figures for 2012, so Nowrasteh’s report had to rely on comments from border agents and local officials about the increases in arrivals rather than the raw Border Patrol data. The anti-DACA bill passed on a party-line vote.

UAC crisis began before DACA was announced

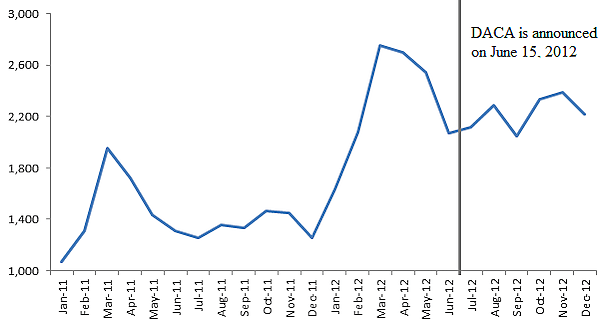

Now, however, the Border Patrol has made available the monthly numbers for 2012. These figures vindicate the Cato argument from 2014, showing unequivocally that all of the increase in children coming to the border in 2012 began before the DACA announcement in mid-June. Figure 1 shows the trend in UAC arrivals for 2011 and 2012. From December 2011 to April 2012, the number of UACs more than doubled from 1,259 to 2,703. Thereafter, the numbers fell and did not recover their peak again until 2013.

Figure 1: Unaccompanied Alien Children (UACs) Arriving in 2011 and 2012 by Month

Source: Customs and Border Protection (CBP)

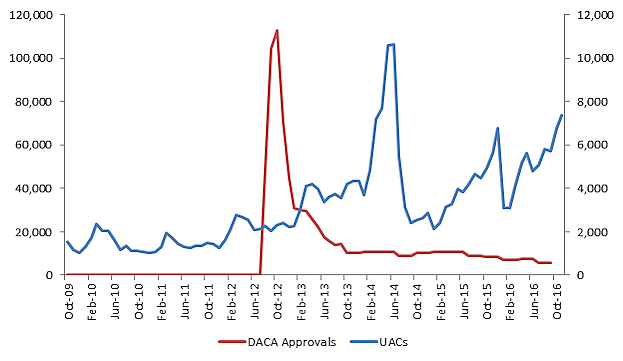

It is true that more than six months after DACA in 2013, the monthly UAC numbers finally rose above the pre-DACA level. But when seen in the broader context, the largest growth occurred much later, shooting up in early 2014. Moreover, as Figure 2 shows, UAC arrivals have fluctuated month-to-month and year-to-year totally without regard to the number of new DACA applications. To the extent that there is a relationship, it is the other way—almost all DACA approvals occurred at a time of relatively low UAC arrivals.

Figure 2: Unaccompanied Alien Children (UACs) Arrivals and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) Approval

Annual UAC figures confirm this impression. The percentage growth in UAC arrivals was the largest in 2009, and while it rose in 2012, the rate of growth remained similar in 2013 and 2014. In 2015, UAC arrivals plunged before rising again in 2016. The first two months of 2017 have seen a remarkable growth over the numbers in those same months in 2016.

Table: UAC Arrivals and UAC Growth Rates

|

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

|

|

UACs |

8,041 |

19,668 |

18,634 |

16,056 |

24,481 |

|

UAC growth |

145% |

-5% |

-14% |

52% |

|

|

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017* |

|

|

UACs |

38,833 |

68,631 |

39,970 |

59,692 |

14,128* |

|

UAC growth |

59% |

77% |

-42% |

49% |

134%** |

*Based on the first two months of the fiscal year, **Compared to the first two months of FY 2016

Source: CBP, CBP

DACA expansion announcement led to no increase in UACs

It would be nice to be able to conduct an experiment to see if announcements of deferring the deportations of minors result in more children coming to the border. While it is impossible to conduct an experiment of this kind perfectly, President Obama provided the next best option in 2014. In November 2014, he announced that he would expand DACA to include anyone of any age—not just those under 31—who arrived before 2010 and would grant three-year work authorizations to recipients.

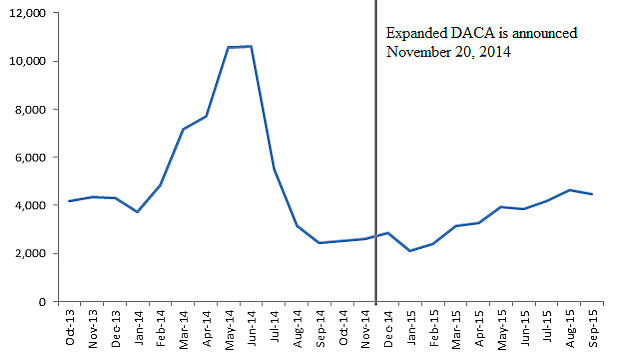

Figure 3 provides the monthly UAC arrivals for fiscal years 2014 and 2015 and notes when the expanded DACA announcement occurred. It is true that the numbers rose slightly over the course of the year, but the peak month saw half as many arrivals as the peak in 2014. Just as DACA did not cause a crisis, the expanded DACA program announcement did not cause one either, and it provides more evidence against the theory that allowing DACA recipients to stay is a significant influence on the children coming to the border.

Figure 3: UAC Arrivals in Fiscal Years 2014 and 2015

Source: See table above

Expanded DACA’s implementation was prevented due to a preliminary injunction issued by a federal judge on February 16, 2015. But three months had already passed since the announcement with no increase in UAC arrivals. Moreover, advocates were hopeful that the injunction would be quickly overturned, and the program implemented that year. In any case, the basis for the purported link between UAC and DACA is that the UACs mistakenly believe that they will be eligible for these programs, not that they actually will be, so it is not clear why the judge’s order would have had any more of an impact on these confused children than President Obama’s specific criteria making them ineligible.

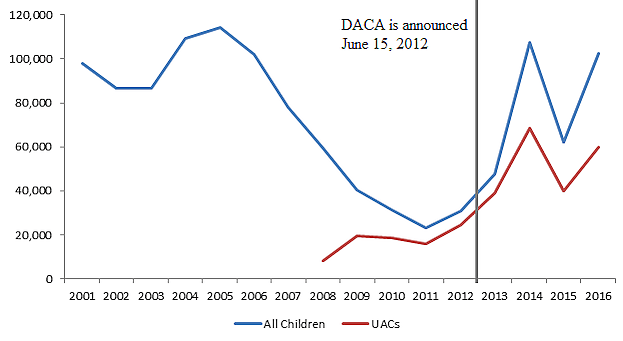

Child migrants are not a recent phenomenon

Perhaps the most important argument against the idea that the child migrant crisis was caused by the actions of the Obama administration is that a similar crisis occurred during the Bush administration as well. Unfortunately, CBP has not made available its UAC numbers prior to 2008, but before the recession, its statistics show that huge numbers of children were coming to the border. The New York Times ran an article about the issue as far back as 2003, noting that Border Patrol was struggling to handle the flow of children. It appears that juvenile arrivals are simply returning to their pre-recession trend.

Figure 4: UAC Arrivals and all Juvenile Arrivals from Fiscal Year 2001 to 2016

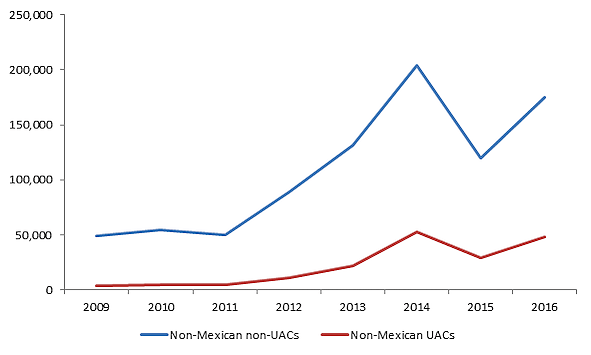

Another reason to believe that the UAC crisis is not related to confusion around DACA is that the recent surge in children is concentrated among non-Mexican arrivals. All of the increase in UAC arrivals is from Central American children. But this surge in UACs has been paralleled by an even larger, in absolute terms, increase among non-UACs—the vast majority of whom are adults who would be ineligible for DACA. Since 2009, the number of overall Mexican apprehensions has steadily dropped year after year, falling over 50 percent over that time, and UAC apprehensions have dropped by a third. These facts point to causes of the surge that are specifically impacting Central America, not Mexico, and all Central Americans, not just children.

Figure 5: Apprehensions of Non-Mexicans by Border Patrol

Source: See Figure 4

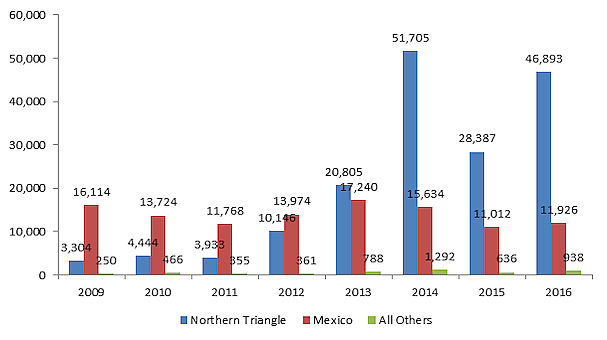

Moreover, the surge was not simply driven by non-Mexican countries generally—which could lead to the conclusion that perhaps something unique is happening in Mexico—but rather was driven entirely from three countries—Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, known collectively as the Northern Triangle. As Figure 6 shows, the rise in child migration is a phenomenon that solely impacted these three countries. This makes it extremely unlikely that the cause of the crisis is a general confusion about DACA among children outside of the country.

Figure 6: UAC Arrivals by Country of Origin

Source: See Figure 4, Figure 1

DACA was not a contributor to the child migrant crisis, so it should not be used as a justification to end the program. If DACA was an example of executive overreach, Congress should replace it with a permanent program that recognizes that America is home for the vast majority of these young immigrants.