Yesterday we posted the 3,000th conflict to the Public Schooling Battle Map, an interactive database of values and identity-based conflicts in public schools. I thought I would take the occasion to provide an update on the changing number and nature of these very personal conflicts over the last decade.

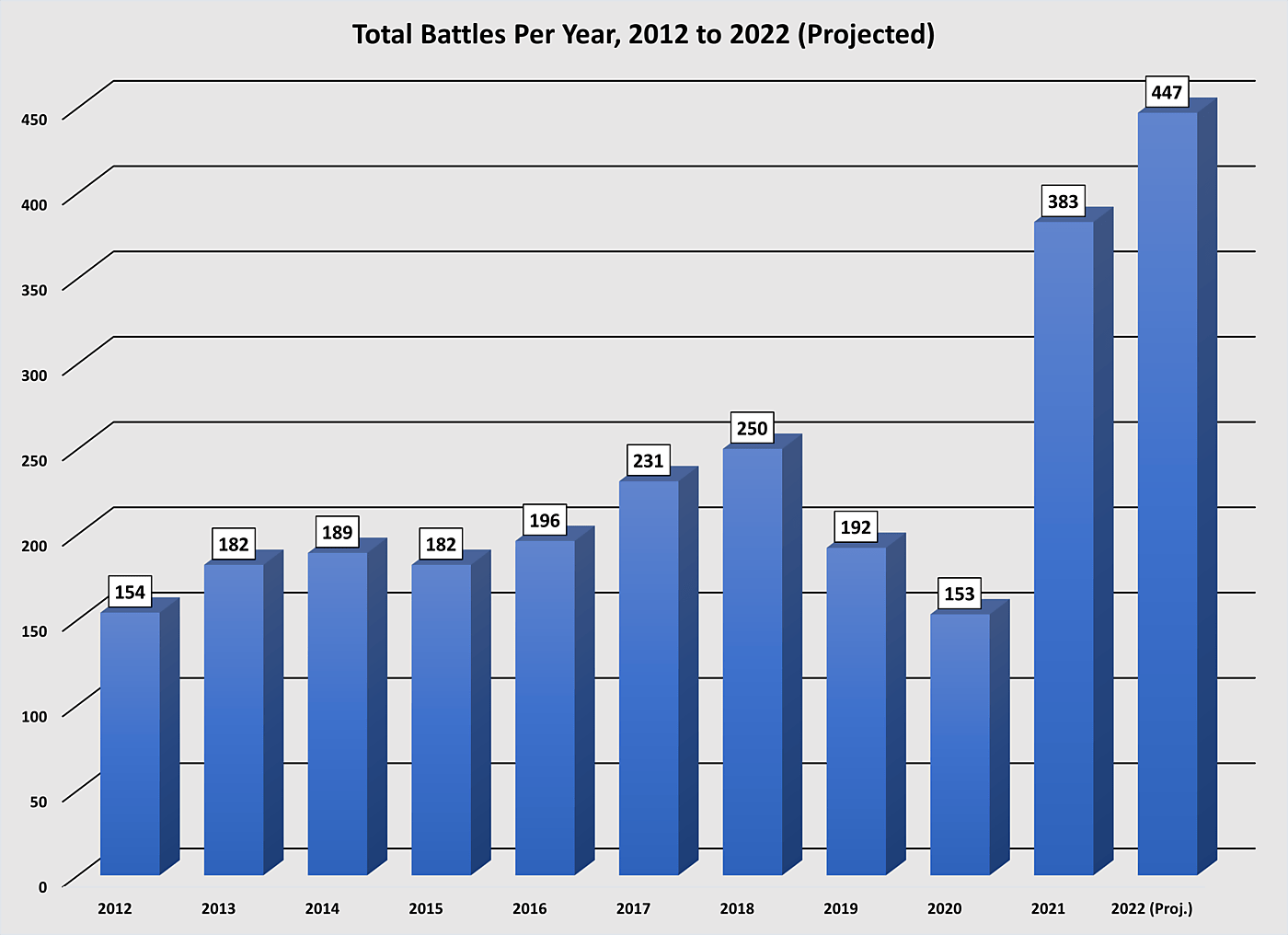

First, as anyone who has been reading education news has likely detected, the frequency of the kinds of conflicts we track has been rising. As shown on the chart above, we are headed for a projected 447 conflicts in 2022, which would eclipse last year’s record. And do not be deceived by the low number in 2020. While 2019 reflects a likely decrease in conflicts in public schools (why is not clear), 2020 was marked by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which greatly disrupted schooling and almost certainly changed priorities from culture war issues to simply getting education up and running again. And there was, in fact, significant conflict, but mainly about when to re-open to in-person learning, rather than over deeply held values or people’s racial, sexual, or other identities.

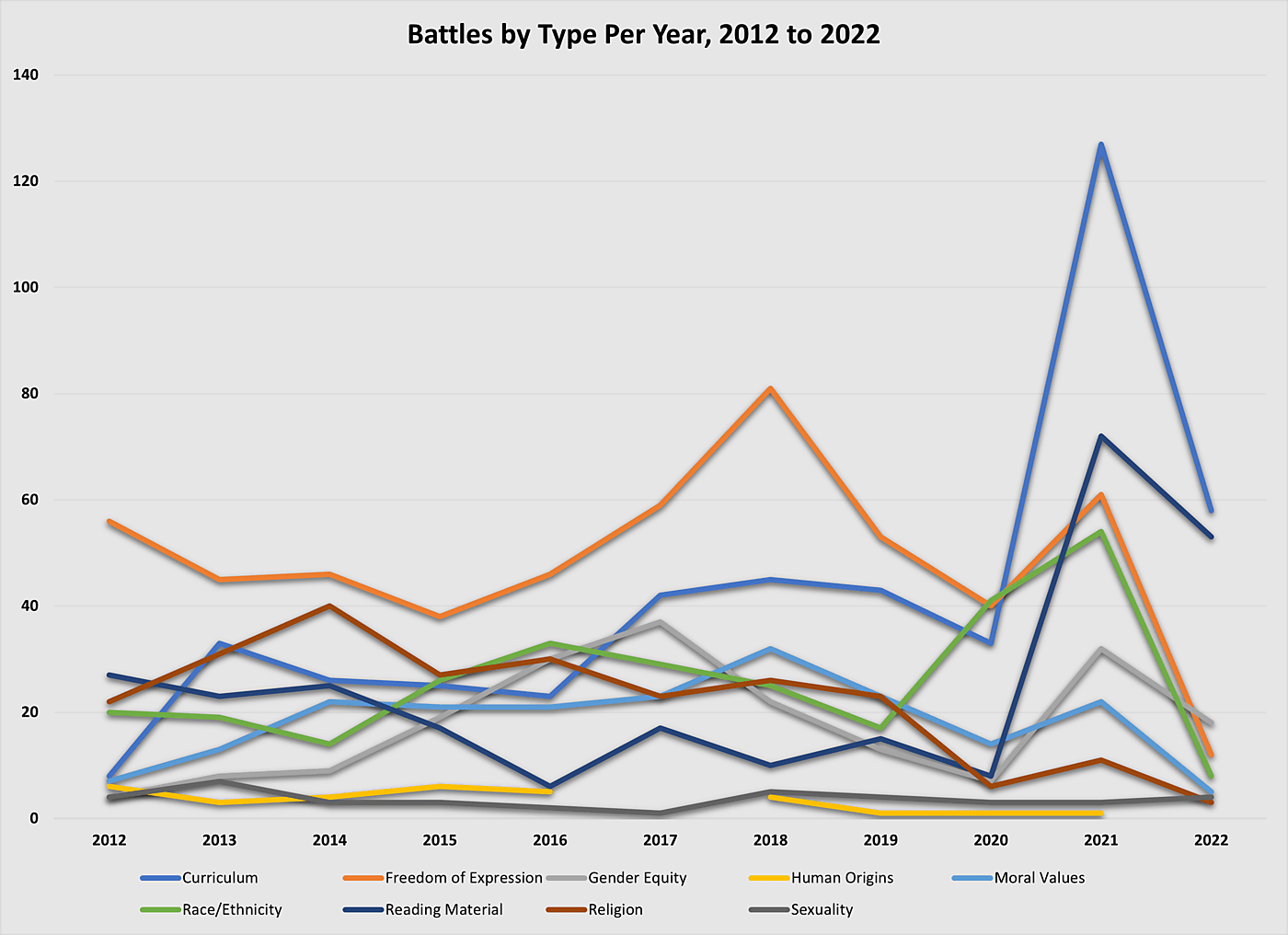

The chart below shows how the dominant types of battles have changed. For most of the decade, conflicts over expression predominated, such as the ability to wear t‑shirts with potentially upsetting messages, whether students could publish articles critical of authorities in school newspapers, or the ability of citizens to speak freely at school board meetings. We’ve also seen a fairly steady decline in battles explicitly concerning religion, such as a football coach’s prayer, or holiday concerts promoting or avoiding Christmas.

The biggest increase has been in curricular battles, which should be familiar to everyone by now. These include conflicts over teaching informed by “critical race theory” or about sexual orientation. This category includes recent efforts in many state legislatures to prohibit “divisive concepts,” and the Florida law dubbed “Don’t Say Gay” by opponents. Similarly, we’ve tracked a big leap in “reading material” conflicts – challenges to books such as Gender Queer and Beloved that are seen as indecent and offensive by some, insightful and supportive by others.

There are important limits to what one can conclude from the Map. There is significant overlap among categories – e.g., a t‑shirt a student is told to remove with a racially charged message – so delineations are not crystal clear. (The t‑shirt example would be categorized as “freedom of expression,” not “race/ethnicity,” as long as the student asserted an expression right.) Also, we find the incidents that populate the Map via media stories, which means first a reporter must learn of a conflict, then we must learn of the article. We likely miss conflicts in small, lightly covered districts. Also, if school battles attract more media attention because culture war becomes a hot topic, we might see increasing articles because more reporters are looking for battles, not necessarily because conflicts have increased.

Finally, while conflict is likely increasing, most districts may be placid. There are roughly 13,500 districts in the country and only about 1,300 have battles on the Map. Of course, many battles are at the state level – the Map contains 556 of those – leaving no district unaffected.

What is causing the rise in conflicts? Almost certainly the same factors driving polarization broadly: changing demographics, racially charged incidents involving police, and evolving mores. But arguably nowhere is such change likely to create higher stakes than in education, which is about nothing less than the formation of human beings. And when diverse people must pay for a single government school or district, it makes heated conflict inevitable.