On Friday, Ross Eisenbrey of the Economic Policy Institute wrote an op-ed in the New York Times titled “America’s Genius Glut,” in which he argued that highly-skilled immigrants make highly skilled Americans poorer.

A common way for highly-skilled immigrants to enter the United States is on the H‑1B temporary worker visa. 58 percent of workers who received their H‑1B in 2011 had either a masters, professional, or doctorate degree. The unemployment rate for all workers in America with a college degree or greater in January 2013 is 3.7 percent, lower than the 4 percent average unemployment rate for that educational cohort in 2012. That unemployment rate is also the lowest of all the educational cohorts recorded.

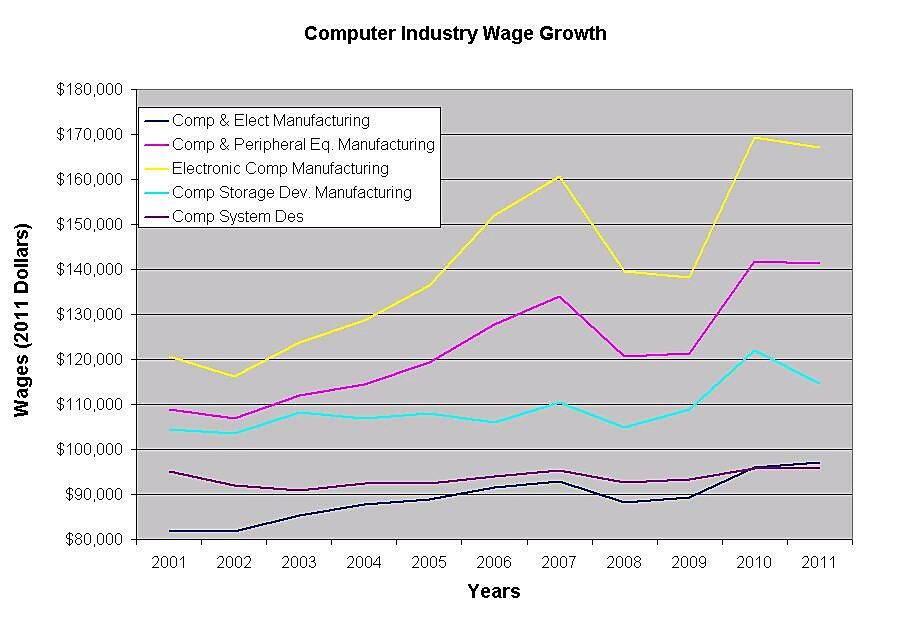

Just over half of all H‑1B workers are employed in the computer industry. There is a 3.9 percent unemployment rate for computer and mathematical occupations in January 2013, and an unemployment rate of 3.8 percent for all professional and related occupations. For selected computer-related occupations from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ “Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages,” real wage growth from 2001 to 2011 has been fairly steady:

11 percent of H‑1B visas go to engineers and architects but wage growth in those occupations has been fairly steady too:

Mr. Eisenbrey concludes that those rising incomes would rise faster if there were fewer highly-skilled immigrants.

The unemployment rates for engineers and computer professionals are low but not as low as they used to be. There are a whole host of factors explaining that, but highly-skilled immigration is not likely to be one.

Mr. Eisenbrey also claims that American firms hire H‑1B visa workers because they are paid lower wages. Complying with certain regulations prior to hiring an H‑1B can cost a firm $10,000, filing and other fees can cost additional thousands of dollars, and legal fees can be steep. The cost of hiring H‑1Bs is high.

Contradicting Mr. Eisenbrey’s story about H‑1Bs lowering American wages, IT workers on H‑1Bs actually earn more than similarly skilled Americans. According to survey data, H‑1B workers are more willing to work long hours and relocate to a job, making them more productive and raising their wages. Additionally, H‑1B engineers are paid $5,000 more a year than American born engineers. If the goal of employers was to hire cheaper workers through the H‑1B visa, they’re going about it in an odd way. The high regulatory costs and wages of employing H‑1B workers incentivizes firms to hire foreign workers when they are expanding and can’t find American workers fast enough.

Mr. Eisenbrey’s doesn’t touch on other characteristics of highly-skilled immigrants such as their high rates of entrepreneurship, inventiveness, or skill complementarity. If the New York Times chooses not to run one of my letters to the editor about those topics, I will be writing about them in the upcoming weeks.